Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the world. Faced with the lack of medical treatment or a vaccine, nations around the globe have opted for the only remedy known against the easily communicable virus –namely, the adoption of social distancing measures that curtail its contagion. As the pandemic rolled from Wuhan, China, to other nations, international borders closed, quarantines were imposed on newcomers and, overall, international mobility came to a near-complete halt. 1See: Aljazeera News. 2020. “Coronavirus: Travel restrictions, border shutdowns by country”, May 22. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/coronavirus-travel-restrictions-border-shutdowns-country-200318091505922.html; Alsema, Adriaan. 2020. “With Closing of International Airports, Colombia Goes on Lockdown”, Colombian Reports, March 19. Available at: https://colombiareports.com/with-closing-of-international-airports-colombia-goes-on-lockdown/; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Returning from International Travel. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/after-travel-precautions.html.

In the United States, the President’s announcement on restrictions placed on international arrivals from 26 countries on March 11, 2020,2See: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-suspension-entry-immigrants-nonimmigrants-certain-additional-persons-pose-risk-transmitting-2019-novel-coronavirus/. led to the State Department’s suspension of exchange programs, which allow qualified foreign-nationals to participate in work- and study-based exchange visitor programs, for, at least, 60 days. Participants in these exchange visitor programs include foreign-born medical school graduates who complete their residency requirements and sub-specialty training in the United States prior to going back home for two years before they can return to the United States–usually through an H1-B or L-1 visa. Many of them actively helped save American lives as the pandemic rolled out throughout the country, either through their medical practice or through research for a COVID-19 treatment and vaccine. Yet, their ability to remain in the country and the continuation of the program, itself, remains uncertain.

Similarly, many international students have found themselves stranded with visas that restrict their ability to work and prevent them from going back home, given their ineligibility for COVID-19 related federal assistance. A few days after the President’s announcement on travel restrictions, on March 20, 2020, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) announced the immediate pausing of most immigrant and non-immigrant visas.3U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “USCIS Announces Temporary Suspension of Premium Processing for All I-129 and I-140 Petitions Due to the Coronavirus Pandemic,” March 27, 2020, https://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/temporary-workers/uscis-announces-temporary-suspension-premium-processing-all-i-129-and-i-140-petitions-due-coronavirus-pandemic.

Immigration restrictions have been further extended on April 22, 2020, when the President signed an executive order that suspended employment-based immigration, family reunification, and the Diversity Visa Lottery program –all under the auspice of protecting American workers from the looming economic crisis. The ban, however, fit well with the stricter immigration policy climate that has characterized President Trump’s Administration. Soon after his inauguration in 2017, the Trump Administration banned foreign nationals from eight countries from entering the United States, reduced refugee admissions, ended new applications for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, ended the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) designations for Sudan, Nicaragua, Haiti, and El Salvador, and began instating “zero tolerance” policies at the border that increased child detentions and family separations.4Pierce, Sarah and Andrew Selee. 2017. “Immigration under Trump: A Review of Policy Shifts in the Year Since the Election.” Policy Brief, Migration Policy Institute.

Within the first nine months of Donald Trump taking office, arrests for immigration violations increased by 42 percent, and non-border deportations rose 25 percent in 2017.5See “Donald Trump takes a hard turn on immigration,” April 5, 2018, The Economist, https://www.economist.com/united-states/2018/04/05/donald-trump-takes-a-hard-turn-on-immigration. Overall, these actions, along with promises of significant regulatory changes to a wide range of programs, have influenced international confidence in the United States and perception of U.S. policies abroad.6These have ranged from the Optional Practical Training (OPT) to the H1-B programs, and included attempts to adjust how the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) calculates “unlawful presence” for international higher education students, and the recent creation of a “Denaturalization Section” by the Justice Department; Grawe, Nathan. 2019. “International Students and U.S. Higher Education”, Econofact; Wike, Richard, Bruce Stokes, Jacob Poushter, Laura Silver, Janell Fetterolf, and Kat Devlin. 2018. “Trump’s International Ratings Remain Low, Especially among Key Allies.” Pew Research Center: Washington DC.

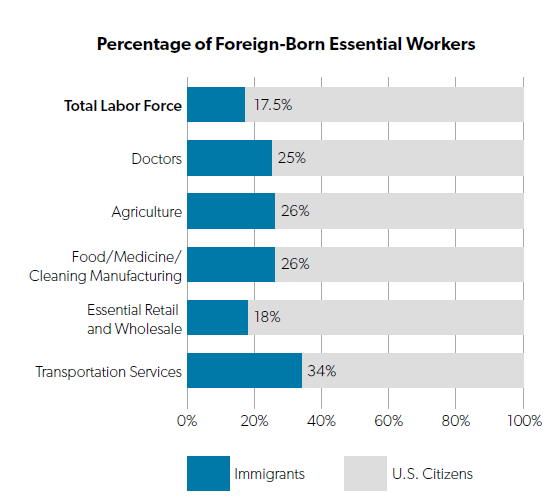

An important challenge in recovering from the pandemic will be fighting perceptions of immigrants as economic and security threats. And instead creating and maintaining an open economy that welcomes the international exchange of ideas that has characterized and fueled growth in the United States for decades. If the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored something, it is the many ways in which immigrants contribute to our economy, keeping Americans safe, healthy, and fed. Immigrants have been leading the response to the pandemic working as health care providers and farmworkers, in the food preparation and delivery services, as well as in cleaning and maintenance services. Families who remember the empty store shelves of March should remember the many migrant workers who continued working the land and distributing food to ensure shelves were full in April.

The Center for Migration Studies estimates that close to 20 million immigrants work in “essential critical infrastructure” categories.7Kerwin, Donald, Mike Nicholson, Daniela Alulema, and Robert Warren. 2020. US Foreign-Born Essential Workers by Status and State, and the Global Pandemic. New York: Center for Migration Studies. https://cmsny.org/publications/us-essential-workers/. One-fourth of all doctors in the United States are foreign-trained.8American Immigration Council. 2018. Foreign-Trained Doctors Are Critical to Serving Many U.S. Communities. Special Report. January, 2018. They are more likely to serve in less lucrative, yet badly needed specialties, such as primary care, as well as in poorer, less educated areas with more minorities–a group that has greatly suffered under the COVID-19 pandemic.9Ray, Rashawn. 2020. “Why are Blacks dying at higher rates from COVID-19?” Brookings, Thursday, April 9. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/04/09/why-are-blacks-dying-at-higher-rates-from-covid-19/ Many of them have been involved in research for treatments and a vaccine against the COVID-19 virus, accounting for 22 percent of all scientific researchers in the country.10Gelatt, Julia. 2020 Revised. Immigrant Workers: Vital to the U.S. COVID-19 Response, Disproportionally Vulnerable. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Similarly, immigrants are key in sectors ensuring Americans are well-fed, such as agriculture (26 percent), food/medicine/cleaning manufacturing (26 percent), essential retail and wholesale (18 percent) or transportation services (34 percent) –all sectors involved in getting food from the fields to our tables.11American Immigration Council. “Fact Sheet: Immigrants in the United States.” April 21, 2020. www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigrants-in-the-united-states.

Despite their distinct contributions to the economy and the well-being of Americans during the pandemic, many immigrants have been largely excluded from the protections provided by Congress under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Families First Act.12Migration Policy Institute. 2020. Mixed-Status Families Ineligible for CARES Act Federal Pandemic Stimulus Check. Available at: migrationpolicy.org The CARES Act excludes not only undocumented immigrants from access to free COVID-19 testing and care, but also many migrants legally residing in the United States under DACA, non-immigrant visas, Temporary Protected Status, or U-visas. While some might be eligible through state-level Emergency Medicaid programs, eligibility depends on whether the applicant fulfills other Medicaid eligibility requirements. Likewise, the tax rebate proposal has excluded mixed-status families and Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITIN) tax filers, obligating many of these households to continue to work, as opposed to staying safe at home, during the early spread of the pandemic.

The more recently passed Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act by the U.S. Congress on May 15, 2020, is a step forward. It would bring significant relief to many immigrant families excluded from the federal assistance provided by the CARES Act. Importantly, from an immigration perspective, would be the protections provided to immigrants currently stranded due to international travel restrictions. Immigrants who were legally present in the United States at the time the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a public health emergency would be protected from any negative consequences associated with their inability to depart the United States or meet specific status adjustments or visa extension deadlines. In addition, the HEROES Act would extend the temporary immigration status and work permits due to expire during the duration of the national emergency period, while rolling any unused non-immigrant visas for the FY2020 to the following year. Finally, DACA and TPS beneficiaries would be protected from deportation for the duration their permits were initially granted, with no additional funds going to immigration enforcement.13Loweree, Jorge. 2020. The HEROES Act Would Provide Aid to Millions of Immigrants Left Out of Other Coronavirus Relief Packages, May 18, American Immigration Council.

While the HEROES Act represents an important first step to reinstating and reassuring migrants’ rights while in the United States, more needs to be done to ensure openness to international exchanges and a faster economic recovery. In addition to terminating immigration bans and normalizing international flows, an important task remains the acknowledgment of migrants’ contribution to our economy and the adoption of policies that recognize and allow for the continuation of such valuable input.

References

1. Aljazeera News. 2020. “Coronavirus: Travel restrictions, border shutdowns by country”, May 22. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/coronavirus-travel-restrictions-border-shutdowns-country-200318091505922.html

2. Alsema, Adriaan. 2020. “With Closing of International Airports, Colombia Goes on Lockdown”, Colombian Reports, March 19. Available at: https://colombiareports.com/with-closing-of-international-airports-colombia-goes-on-lockdown/.

3. American Immigration Council. 2018. Foreign-Trained Doctors Are Critical to Serving Many U.S. Communities. Special Report. January, 2018.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Returning from International Travel. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/after-travel-precautions.html.

5. Gelatt, Julia. 2020 Revised. Immigrant Workers: Vital to the U.S. COVID-19 Response, Disproportionally Vulnerable. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

6. Grawe, Nathan. 2019. “International Students and U.S. Higher Education”, Econofact.

7. Kerwin, Donald, Mike Nicholson, Daniela Alulema, and Robert Warren. 2020. U.S. Foreign- Born Essential Workers by Status and State, and the Global Pandemic. New York: Center for Immigration Studies.

8. Loweree, Jorge. 2020. The HEROES Act Would Provide Aid to Millions of Immigrants Left Out of Other Coronavirus Relief Packages, May 18, American Immigration Council.

9. Migration Policy Institute. 2020. Mixed-Status Families Ineligible for CARES Act Federal Pandemic Stimulus Check. Available at: migrationpolicy.org.

10. Pierce, Sarah and Andrew Selee. 2017. “Immigration under Trump: A Review of Policy Shifts in the Year Since the Election.” Policy Brief, Migration Policy Institute.

11. Ray, Rashawn. 2020. “Why are Blacks dying at higher rates from COVID-19?” Brookings, Thursday, April 9. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/04/09/why-are-blacks-dying-at-higher-rates-from-covid-19/.

12. Wike, Richard, Bruce Stokes, Jacob Poushter, Laura Silver, Janell Fetterolf, and Kat Devlin. 2018. “Trump’s International Ratings Remain Low, Especially among Key Allies.” Pew Research Center: Washington DC.