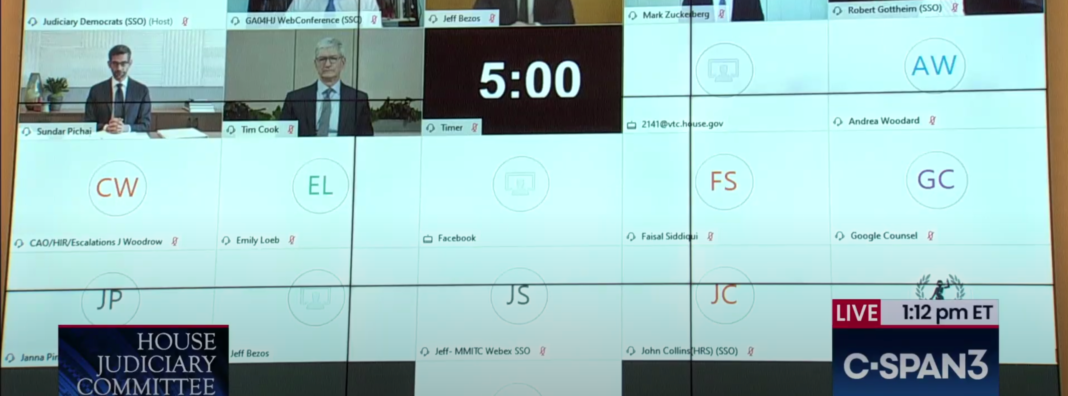

The CEOs of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google are testifying before Congress today in a hearing billed as crucial for the future of both antitrust law and Big Tech’s relationship with Washington. Putting these companies under the glare of a national spotlight isn’t new, and is just the latest episode in Congress’ ongoing efforts to increase the public scrutiny of these companies.

There is little doubt that attacking tech companies scores cheap political points. With trust in these companies at an all-time low, they are easy sparring partners for the Congressional members sitting on the other side of today’s virtual witness table.

A New CGO/YouGov poll measures how people viewed tech companies, their impact on their lives, and the prospects of breaking them up. Nearly 70% of Americans said they believe tech companies are too big, and 44% said they thought the government should break them up.

This polling looks bad for America’s tech giants. After all, there is momentum behind the techlash and the growing animus toward these companies. This is being reflected in the halls of Congress, state attorneys general’s offices, and the pages of nearly every major news outlet.

But unpacking the results of our latest survey in the runup to today’s hearing, one trend is evident: Much of the anti-tech sentiment is the product of beltway politics. Many questions we asked about these companies seem to divide Americans based on those who closely follow political news and those who do not. If you closely follow American politics, you are more apt to respond that tech companies are too big, the government should break them up, and your life would be improved if they were broken up. If you hardly follow American politics, you are likely more skeptical of these ideas.

On the surface, it is easy to watch what is happening today and think that Americans have soured on tech companies. In reality, however, this is more a reflection of insider politics than anything else. Our poll results indicate that, in many ways, the techlash is a beltway-manufactured crisis echoed only by those who follow it closely.

Are tech companies too big? There is a stark contrast in responses between those who closely follow political news and those who do not.

Two questions we asked, about whether tech companies are too big and if the government should break them up, outline the divide between those viewing tech through a political lens and those who are not.

When it came to whether tech companies are too big (see the chart below), more than three quarters (77%) of those who indicated they follow politics most of the time agreed that tech companies are too big. Among those who follow politics hardly at all, agreement drops to 54%. That amounts to a 23% difference based on whether you are following political news closely. This divide is also seen by how these groups disagreed with this statement: 15% of those who follow politics closely did not think that tech companies are too big, while nearly a third (31%) of those who hardly follow politics disagreed. Finally, nearly twice as many of those who hardly follow politics answered they were unsure compared to those who follow politics most of the time.

Now, when it comes to breaking up tech companies (see the chart below), we see the same divide based on whether or not respondents followed politics. 53% of those who follow politics closely agreed that the government should break up tech companies, a little over one quarter (27%) disagreed, and 17.4% said they were unsure. Among those who hardly follow political news, the responses were divided nearly evenly into a third in agreement, disagreement, and unsure.

Whether tech companies are too big and ought to be broken up are complex questions revolving around market definitions, market share, consumer welfare, and a whole host of considerations that make it impossible to determine with a public opinion poll. However, lately it seems that politicians are increasingly using public sentiment around these companies as fuel to support calls for their breakup. We should be skeptical of such a route. This is not how antitrust and competition policy is done in America.

More importantly, policymakers ought not fall into the trap of listening to the echo chamber. These results indicate that those who follow politics are more likely to agree with calls to break up big tech, but that should not be mistaken as a signpost for where those outside the beltway and not plugged into the 24/7 news cycle fall on these issues.

The Beltway believes tech breakups would benefit Americans. The rest of America is unsure.

When it comes to specific questions of whether breaking up specific tech companies will make our lives better or worse, responses fall similar to the ones outlined above. In the chart below, however, you’ll see the overall responses to whether Americans think their lives would be better or worse if specific tech companies were broken up.

Before digging into them further, it is worth highlighting that Americans may not fully understand what tech breakups mean for them. The most popular response to how a breakup would affect respondents was doubt. At least a third of respondents were unsure for each company.

Breaking up companies may also be viewed by some respondents as a punitive measure rather than anything else. For example, 35% of respondents said they would be “somewhat better off” or “better off” if Twitter were broken up. But Twitter represents less than ten percent of the social media websites in the United States based on the share of visits. More importantly, because Twitter offers a single product, it really has nothing to break up. Similarly, 15% of respondents said breaking up Zoom and nearly 10% said breaking up Slack would make their lives better off to some degree. It is difficult to fully understand how those breakups would occur, or how they would improve consumer welfare and competition, and yet there are respondents voicing support for their destruction.

Now, turning to the results based on how closely respondents follow politics we get another look at how it is shaping the way we view these companies. Among those who follow political news most of the time, 42.3% of respondents said their lives would improve if Twitter were broken up, while 16% said they would be worse off in some way. Among those who follow political news hardly at all, 25% said they would be better off while nearly a third of respondents (31%) said they would be worse off in some way.

This same breakdown exists for Facebook: 54% of those who follow politics closely think breaking up Facebook would make them better off in some way, while 34% of those who hardly follow politics agree. Conversely, 16% of those who closely follow politics said their lives would be worse in some way versus 28% of those who hardly follow politics. Google and Amazon also see similar breakdowns by those following (or not following) political news.

The less you follow politics, the less likely you are to trust politicians to regulate social media.

Finally, in a trend across our entire poll, whether or not you think that the government should be more involved in regulating social media companies seems to be shaped in large part by whether or not you follow political news. Among those following politics most of the time, 57% of respondents agreed that the government should be more involved. 46% of those that hardly follow politics agreed. Similarly, 31.4% of those who follow politics closely and 36% who follow hardly at all disagreed.

As with the other findings from our poll, this continues to support the conclusion that politics is likely shaping tech views more than Americans’ actual relationship with these companies.

Politics is shaping everything about how we view these companies — including our trust in them.

Turning back to Americans’ trust in tech companies, there are massive differences in trust between those who follow politics and those that do not. Take, for example, responses to trust in Google. Among those that follow politics most of the time, 47% distrust the company while 25% trust them. Among those that hardly follow politics, 18% distrust while 57% trust the company. Breaking these numbers down more, only 7% of those who closely follow politics completely trust Google while 23% of those who hardly follow politics completely trust Google. These differences are dramatic. Especially considering the breakdown is based solely on whether or not someone follows politics.

On a scale from 1 to 5 where 1 is completely distrust and 5 is completely trust, please indicate how much you trust Google below to collect and use your personal information/data.

Ideology is also playing a role in how Americans view tech companies. Breaking down trust in Google by party identification, 26% of Democrats distrust Google while 58% of Republicans distrust Google. 40% of Democrats trust Google while 25% of Republicans trust Google. A similar breakdown occurs for companies like Twitter, Apple, and Microsoft.

Why we should care about how politics is shaping today’s tech policy conversations

Today’s hearing is less a reflection of how Americans view tech companies and more of a symptom of how America’s divided politics are shaping nearly every aspect of our lives. We should resist the urge to let this happen. More importantly, we should not let politics shape our most vibrant and innovative industries.

Conversations around tech platforms should not become unmoored from the underlying principles that have been the bedrock of American antitrust and competition policy. We should not confuse political discussions with policy considerations. Understanding what is behind the techlash will give us a better perspective on how to evaluate these sentiments in the proper context.