*Part 1 of a 2 part series on micromobility after COVID

As cities struggle to return to normal in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a looming fear that traffic will be worse than ever. To prevent the impending Carmageddon, cities around the world are backing micromobility. E-scooters, E-bikes, bikes, mopeds, and other forms of micromobility present alternative options for commuters going to work.

The US can also join the micromobility revolution. US cities can encourage more people to consider micromobility in two easy steps: First, cities can build more infrastructure dedicated to micromobility. Second, states can reexamine their electric vehicle licensing laws.

Traffic and transit patterns post-COVID

The few cities that have already opened up have seen an increase in traffic and air pollution. Shanghai and Beijing reached pre-COVID traffic levels almost immediately after opening up. In Wuhan, car sales are booming. In the US, traffic could be 30 percent higher than its pre-COVID numbers.

The rise in car traffic comes from the fear of COVID-19 transmission from public transportation. Still, it is easy to understand why people are concerned. Despite efforts to clean and disinfect subways and buses, many people will likely still be scared to ride them due to continued efforts toward social distancing to prevent further spread of the virus.

Yet if people continue to replace public transit with cars, traffic will increase. The graph below shows how driving and walking have increased as places open up, yet public transit users remain low.

Source: Apple Mobility Trends Report

In New York City, subway ridership has declined more than 80 percent from 2019 numbers. Similarly, bus ridership has fallen by 50 percent. Similar trends can be seen in most major US cities. The graph below shows how public transit usage in major US cities has declined significantly in the last few months. Every line represents a different US city.

Source: Moovit

Micromobility as the solution

One promising way that cities can deal with impending traffic congestion is by clearing a path for micromobility. E-scooters, e-bikes, mopeds, even electric skateboards provide an alternative transportation solution that helps keep cars off the streets.

Public transit commuters are using micromobility as an alternative to their regular commute. Gotcha, an e-mobility company, saw a surge in ridership from February to May. The company saw a 1,051% increase in trips per day in Baton Rouge and a 216% increase in Charleston. Philadelphia has seen a rise in trail users up to 471%. Chicago’s bike share users doubled in March. New York’s Citibikes saw demand rise by 67%.

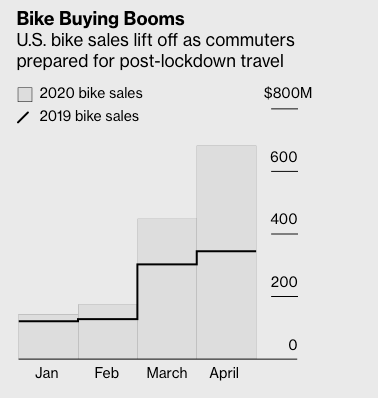

Demand for bikes is so significant that bike sales nationwide have increased, and have left some shops without any supply. If you plan to buy a bike, you will most likely have to wait for weeks to get one.

Source: Bloomberg

This data suggests that micromobility can be an essential means of transportation when other options are down. And micromobility may play a larger role even after the current public health crisis has subsided. Now is the time to allow our cities to innovate and make way for alternative modes of transportation. Here are two things that we can do to encourage micromobility in our cities.

1. Build micromobility infrastructure

According to the US Census Bureau, only about 0.6% of the workforce commuted to work by bicycle in 2017. In cities of at least 60,000 people, this number increased to 5%. And about 1% of the workforce uses a bike-share service. The low number of bike commuters is not surprising. After all, the US has been built around cars, providing very little room for alternative transportation systems.

Having a dedicated space for micromobility users could increase ridership. The primary infrastructure that cities should build is protected bike lanes. Why are protected bike lanes so important? Because bicyclists and other transportation users are at risk in cities that are designed for cars. In 2019, most of the fatal accidents involving an e-scooter or a bike involved a car.

Simply separating micromobility from cars could go a long way. According to a recent study by the University of California, bike trips could increase from 8% to 40% if bicycling was safer. E-scooter company Bird calculates that protected bike lanes could eliminate up to 90% of casualties caused by riding a bike or a scooter.

During the lockdown, cities around the world are installing temporary bike lanes. These temporary bike lanes are makeshift solutions to protect cyclists or other micromobility users. The barriers used varied from traffic cones to concrete slabs. This flexibility makes them easy and cheap to create. Take Bogota, for example. The city created 47 miles of temporary bike lanes during COVID to provide an alternative to transportation — on top of their already existing 341 miles. What is more impressive is that 13 of those miles were literally built overnight.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many US cities like New York, Oakland, Philadelphia, Denver, and Austin have closed streets or created temporary bike lanes to make way for pedestrians and bicycles. However, these changes shouldn’t disappear after cities start reopening. Instead, it should be the first step towards creating more permanent infrastructure for micromobility. Cities can use this opportunity to design streets to support mobility options other than cars.

Some cities are already planning to make this temporary bike infrastructure permanent after COVID. Milan is investing in micromobility by converting 22 miles of road space into bike lanes and pedestrian areas. France is investing in developing a bike-friendly city and keeping cars out after lockdown ends. Paris pledged to create a 400-mile bike network to provide an alternative to public transit. In the US, Seattle Mayor Jenny A. Durkan said the city would keep the 20 miles of streets it closed even after it reopens. So far, it is the only city to have committed to making its infrastructure permanent.

Temporary bike lanes are the first step towards creating a more permanent infrastructure. They could help create a safer environment not only for bikers but for those riding e-scooters and other forms of micromobility. Temporary lanes allow cities to test what streets they want to convert, the length of the trails, and the materials they need. With this in mind, cities can develop short, medium, or long-term proposals for micromobility infrastructure. The important part is that we allow users to feel safe enough to choose micromobility as their primary commuting option.

2. Improve how states regulate e-bikes

Many times it is the regulations surrounding the purchase of micromobility vehicles that prevent people from buying them. There is a wide variety of electric micromobility laws from state to state. States classify and regulate e-bikes differently, making it hard to know where they are legal or not. Some states, like Mississippi and Kentucky, don’t even have a classification for e-bikes, making it unclear how they are regulated.

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures

Worse yet, in 17 states, e-bikes are classified as motor vehicles, along with mopeds or scooters — a completely different kind of transportation. In these states, users are required to have a license, registration, and insurance to use an e-bike.

Studies have shown that there is not much difference between e-bikes and traditional bikes. They are functionally the same; they have the same average speed and similar injury rates. With e-bikes being closer to a traditional bike than a motor vehicle, they should be classified as such.

The confusing regulations around e-bikes and other forms of electric micromobility serve as a deterrent to people who may want to use them to commute. Some recommend a nationwide classification for low-powered electric vehicles like e-scooters and e-bikes. Others, such as People for Bikes, are leading an effort for states to classify and regulate e-bikes properly. Regardless of how we get there, one thing is certain: Clear statewide policies surrounding e-bikes and their operation could help support the growth of micromobility.

A new future for mobility

The post-COVID world can inspire us to rethink how our cities are designed. It presents an opportunity to entice people to use micromobility, increase the number of commuters by bicycle and e-mobility, and mediate what is likely to be a surge in driving in months to come. All the commuters that will not be taking public transit when they return to work could be given another option for their commute. But for this to happen, cities need to act. Traffic counts are currently lower than normal. Now is the time to build more bike lanes, to clarify and liberalize regulations, and to provide greater choice in how Americans get to work.