If you could move from your current home to take a job paying four times more than you make now, would you make the move?

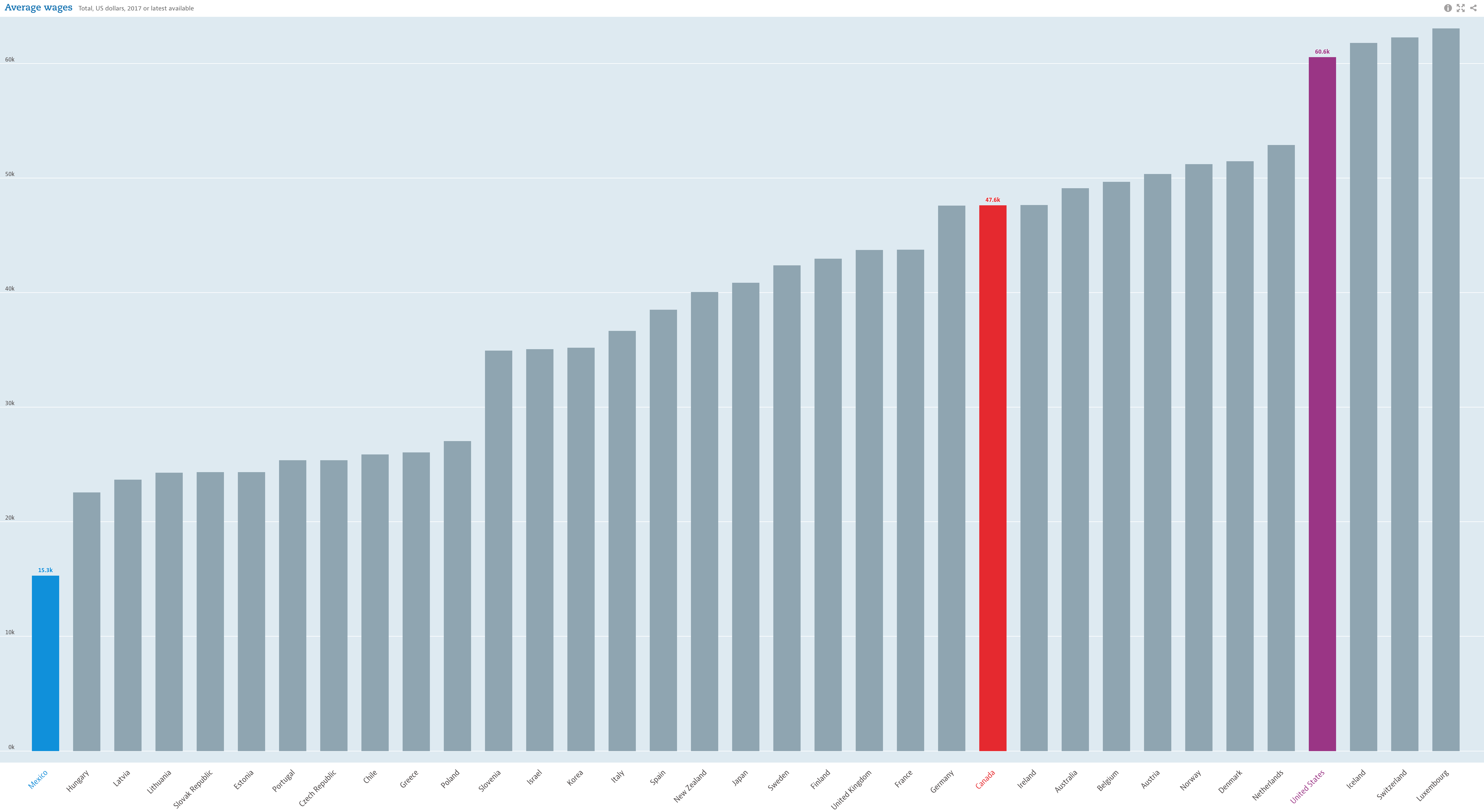

Consider this chart from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) of average annual wages across the world. The blue column at the far left is Mexico, the center-right red column represents Canada, and the purple on the right is the United States.

The OECD’s figure shows that at $60,000, the average US wage is about four times greater than the average wage in Mexico. In a rough sense, a person in Mexico who is dropped into New York can expect to quadruple their wages. There are all sorts of frictions and rough edges to this, like the different cost of living in these countries, the costs of moving, and whether or not an immigrant expects to get into the US.

Yet even after considering the hypothetical’s limitations, there’s still a lot to be learned from it about why people immigrate to the US. Research verifies that migration flows are related to differences in economic opportunity in different places. During periods of economic downturn in the US, for example, fewer immigrants move into the US.

That makes it clear what immigrants get out of their move, but what effects do immigrants have on the economies of the countries that they move into? There’s a lot of research on that question, and the key takeaway is that immigrants contribute a lot as well.

Immigrants bring new ideas

There’s a growing body of research about how immigrants spur innovation. The theory is simple. Immigrants have new and different ideas and when they come into a new area, their new ideas can cross-pollinate between industries and groups.

But the theory can also be more complicated. Immigrants may be less expensive to hire, leaving companies with more resources to spend on innovation. One example of this is the H-1B visa program, which gives employers the ability to temporarily hire specialized foreign workers.

Research by Gaurav Khanna and Munseob Lee from the University of California San Diego examined firms that participated in the H-1B program. As Khanna told journalists, “We found companies with higher rates of H-1B workers increased product reallocation — the ability for companies to create new products and replace outdated ones, which in turn, grows revenue.” That’s additional revenue that the company can invest in expansion and hiring other workers as well as better serving their customers, so this benefits both immigrants and natives.

Another way that immigrants boost innovation may be because many of them tend to work in science and engineering fields. Because immigrant flows concentrate in occupations that push the frontiers of science and technology more than other careers, immigrants boost patenting, which is a common measure of innovation. Economists Jennifer Hunt and Marjolaine Gauthier-Loiselle examined just this pathway in a 2010 paper. They conclude that “a 1 percentage point increase in immigrant college graduates’ population share increases patents per capita by 9–18 percent.”

Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle’s paper finds a substantial amount of new ideas generated by immigrants. It’s a separate mechanism boosting innovation than Khanna and Lee found. Patents are new ideas, but Khanna and Lee were looking at incremental improvements. So immigrants both improve existing ideas and generate new ones, which are two important measures of innovation that contribute to improving everyone’s welfare.

Immigrants change what native workers do for the better

Immigrants bring new ideas and help spur innovation, but how do they impact native workers? Some research suggests that influxes of immigrants lower the wages of people already here, especially low-skilled natives, while others find little to no effect on wages regardless of skill level.

Part of that discrepancy can be explained in how immigrants change what natives do. Because immigrants have different skill sets than native workers, they usually complement existing workers by making them more effective. That doesn’t mean the economy or native workers are unchanged, however. Fundamentally, research on immigration shows that labor markets are dynamic. They change as people enter and exit them and the individuals that remain within them change too, based on who enters and exits.

For example, research by Jennifer Hunt shows that natives increase their investment in education after immigrants enter their labor markets. Other research shows that natives upgrade to new and different roles that capitalize on their differences from immigrants. After all, if immigrants were exactly the same as natives, then it would be reasonable to expect that they would replace natives or compete down the wages of natives. Yet that’s obviously not true. Immigrants differ from native workers in education levels as well as language ability, and that allows both groups to take advantage of these differences by working different types of jobs.

Those differences between natives and immigrants hold even in low-skilled occupations. Researchers Stephen Devadoss and Jeff Luckstead examined the effect of immigrants on productivity in vegetable production as well as the displacement effect and the wage reduction effects of immigrants on natives. In line with most research, they find only a small displacement effect for low-skilled natives. Specifically, each immigrant who moves into the labor market displaces only 0.0123 domestic workers. They find similarly inconsequential effects on native workers wages.

What Devadoss and Luckstead find for total productivity is more impressive. They estimate that each immigrant worker increases “vegetable production by $23,457 and augments the productivity of skilled workers, material inputs, and capital by $11,729.” That’s a substantial improvement and a common result in research on immigration. Often researchers asking similar questions to Devadoss and Luckstead’s find that immigrants complement native workers much more than replace them. Studies often find no negative effects, minor wage losses for low-skilled natives, and sometimes even positive effects. In general, the overall effect is an economic benefit to the US.

Immigrants love cities, why?

A new working paper by Joan Monras and Christoph Albert examines a third avenue for how immigrants benefit the economy: they love living in cities.

Think of cities as massive job fairs where employers and employees meet and negotiate employment. Economic theory developed by immigration scholar George Borjas and verified through empirical research by others shows that immigrants follow the jobs. That is, immigrants speed up the economy by moving to areas with more employment opportunities. This is part of why immigration slows during economic recessions.

When immigrants move into the US, they want to choose the best job fair that they can find. In general, major cities are the most productive areas and thus offer the highest pay.

But what immigrants see as their best job options also depends on what immigrants want to do with their earnings. Immigrants often send money home to their relatives or family, and that affects where they want to live. In fact, it makes them somewhat less responsive to the higher cost of living in cities. That’s because they want to consume some of what they earn in their home country, which will generally have a lower cost of living than the US city that they work in.

Immigrants, according to the research, actually seek out places where the earning differential is greater between their home and the US cities they move into. That means that immigrants move to cities that are more productive where they can earn a higher wage and spend some of their money back at home where the cost of living is lower.

As Monras and Albert find in their research, an immigrant who wants to consume part of her income in her country of origin prefers to live in a city that is twice as expensive if wages are also twice as high, all else equal. That’s a fundamental difference between most US natives and immigrants. And it has profound implications for overall US productivity.

In total, Monras and Albert find that overall worker productivity increases by around 1 percent because immigrants work in those more productive cities. In turn, that worker productivity boost increases the welfare of native workers by about 0.35 percent. Those are small percentages, but they’re meaningful in real terms because of the massive size of the US economy. Even a small percentage increase in the US’s $20 trillion dollar economy means a big bump overall.

The fundamental takeaway from existing research on immigration is that when people move into an area to work, they bring prosperity. Whether it’s immigrants bringing new ideas into the US that create better projects for consumers or immigrants boosting overall productivity by gravitating towards high-productivity areas where employers need workers, immigrants move economies upwards. As more workers come into the country, they build greater capabilities in the US as well as complement the workers who are already here.

Policymakers working on immigration should pursue ways to bring more immigrants into the United States. Economic research is clear that because immigrants make the United States’s companies more innovative and productive, encouraging greater immigration will improve the lives of both immigrants and Americans.