Introduction

In 1978, the Supreme Court of the United States held that, in enacting the Endangered Species Act (ESA), “Congress intended endangered species to be afforded the highest of priorities” and that economic costs should play no role in the act’s enforcement or interpretation.1Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153, 174 (1978). In response, Congress amended the ESA in 1978 and 1982 to clarify the relevance of economic impacts in the listing and critical habitat designation process.2Endangered Species Act Amendments, Pub. L. No. 95-632, 92 Stat. 3751 (1978); Endangered Species Act Amendments of 1982, Pub. L. No. 97-304, 96 Stat. 1411 (1982).

This paper seeks to better inform efforts to promote effective conservation methods by examining the legal requirements of critical habitat designations under the ESA, as they pertain to economic impacts. I examine the legislative history of the 1978 and 1982 amendments to demonstrate what Congress was hoping to achieve with those changes. I then look to how administrative agencies have interpreted and enforced the ESA’s economic impact provisions to discern if agency actions are consistent with the purpose of the statute itself. I then survey critical habitat litigation to see how courts have interpreted the ESA’s economic impact provisions.

Next, I examine how the legal regime surrounding the interpretation of the ESA has affected knowledge of the economic impacts of critical habitat. The Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service, the two agencies charged with administering the ESA, take a narrow view of the role critical habitat plays in the endangered species conservation process.3US Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Regulations for Listing Species and Designating Critical Habitat, 84 Fed. Reg. 166 (August 27, 2019). The Services believe the listing of a species is the main regulatory tool to protect endangered species. As a result, they state that most of the costs, and benefits, of endangered species protection come from listing a species as endangered or threatened, rather than from designating critical habitat.4Ibid The agencies’ economic impact analyses of critical habitat reflect this position.

Unfortunately, there has been little independent analysis of the economic impacts of critical habitat designation. The few such studies on this topic suggest that the Services are likely underestimating the costs of designating critical habitat. If this is true, then the Services are likely making suboptimal decisions regarding critical habitat.

Knowing the true costs and benefits of critical habitat designations can assist in selecting the most eco- nomically efficient conservation methods. But first, we need accurate information about the economic impacts of critical habitat. For effective conservation to take place, economists and other scholars should research the impacts of critical habitat to inform policymakers and the public about the effects of critical habitat designation.

The Endangered Species Act

Precursors to the Endangered Species Act

In the decade before Congress passed the ESA, it enacted two minor statutes intended to protect endangered species. With the 1966 Endangered Species Preservation Act, Congress authorized limited protections for endangered species.5Endangered Species Preservation Act, Pub. L. No. 89-669, 80 Stat. 926 (1966). The statute directed the Secretary of the Interior and other federal agencies to “protect species of native fish and wildlife” and, “insofar as is practicable and consistent with the primary purposes” of those agencies, “preserve the habitats of such threatened species on lands under their jurisdiction.”6Ibid., §1(b). The primary method of achieving these goals was to penalize the taking or capturing of threatened species on lands within the National Wildlife Refuge System and to authorize the Department of the Interior to purchase lands to expand that system.7Ibid., §§ 4(c), 2(b).

In 1969, Congress passed the Endangered Species Conservation Act.8Endangered Species Conservation Act, Pub. L. No. 91-135, 83 Stat. 275 (1969). The act prohibited the importation of animals threatened with extinction. It also directed the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of State to work with other nations to encourage conservation practices to enhance the habitat of any animal imported into the United States.9Ibid., § 5.

The Original ESA

In 1973, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act.10Endangered Species Act of 1973, Pub. L. No. 93-205, 87 Stat. 884 (1973). The ESA builds upon the previous statutes by outlawing the “take” of endangered, and certain threatened, species.11Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1533(d), 1540 (2020). The statute defines “take” as to “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect” a listed species.12Ibid., § 1532(19). Anyone who “knowingly” violates the take provision of the act is subject to civil or criminal penalties.13Ibid., § 1540. The act also authorizes citizen suits that allow anyone to sue to prevent the take of a species.14Ibid., § 1540(g)(1).

The 1973 bill introduced the concept of “critical” habitat but did not expressly define the term. The only reference to critical habitat was in section 7, which required (and still requires) federal agencies to consult with the Department of the Interior to ensure that federal programs do not “result in the destruction or modification of habitat” that the Secretary of the Interior or Secretary of Commerce determines “to be critical.”15Endangered Species Act of 1973, 892.

Like its predecessor, much of the habitat focus in the 1973 bill was on acquiring land for species’ protection. Section 5 sets out a land acquisition program that authorized the secretaries to acquire land to conserve endangered or threatened species, and that allocated funds to carry out that purpose.16Ibid., 889.

The legislative history also reflects a desire to protect habitat through land acquisition. The Senate report on the bill stated that one of the needs for new endangered species legislation was to “lift the statutory restrictions that existing law places on authorization of monies for habitat acquisition from the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act, and extend to the Secretary land acquisition powers for such purposes from other existing legislation.”17Senate Committee on Commerce, Endangered Species Act of 1973: Report (to accompany S. 1983), S. Rep. No. 93-307, at 3 (1973).

Because the ESA did not define “critical habitat,” the two agencies responsible for administering the ESA issued guidance and regulations interpreting the term.18The ESA grants the Department of Interior authority over land and freshwater species and grants the Department of Commerce authority over marine species. Both the Department of Interior and the Department of Commerce have created agencies for promulgating regulations under the ESA (the Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Services, respectively). The agencies have jointly adopted critical habitat regulations, but most of the controversies involve the Fish and Wildlife Service. Therefore, most of the discussions in this paper will involve the Fish and Wildlife Service. The agencies defined “critical habitat” as “any air, land, or water … and constituent elements thereof, the loss of which would appreciably decrease the likelihood of the survival and recovery of a listed species or a distinct segment of its population.”19United States Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service, Joint Regulations (United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior and National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce), 43 Fed. Reg. 2 ( January 4, 1978). The areas included “any portion of the present habitat of a listed species and may include additional areas for reasonable population expansion.”20Ibid.

The Supreme Court Interprets the ESA in Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill

In 1978, the Supreme Court first interpreted the new ESA.21Tennessee Valley Authority. The lawsuit concerned a hydroelectric dam along the Little Tennessee River. The Tennessee Valley Authority had almost completed the federally funded dam when a University of Tennessee ichthyologist discovered the endangered snail darter in the river around the dam.22Ibid, 18–59. The Secretary of the Interior determined that, in addition to the risks to the fish itself, the dam threatened the snail darter’s habitat.23Ibid., 172. As a result, the Secretary determined that the dam project could not be completed.

The Tennessee Valley Authority argued that Congress’s continued appropriation of funds for the dam, even after the snail darter was discovered, demonstrated that Congress intended to supersede the requirements of the ESA in this case.24Ibid., 192, 193. The court rejected that argument and stated that, through the ESA, “Congress intended endangered species to be afforded the highest of priorities.”25Ibid., 174. The court concluded that the purpose of the ESA was to protect endangered species whatever the cost, and that Congress thought the value of endangered species was “incalculable.”26Ibid., 187–88.

In reaching its decision, the court relied on the language and legislative history of section 7.27Ibid., 181–82. In the court’s view, section 7 required federal agencies to take every measure within their regulatory power to avoid jeopardizing an endangered species or threatening its critical habitat.28Ibid., 183. The court’s decision elevated the protection of endangered species and their critical habitat above any other policy decision. Federal agencies were to avoid risk to listed species and their critical habitats, whatever the costs. As Justice Powell said in his dissent from the decision, the only requirement to “destroying the usefulness of even the most important federal project” would be if the secretary determined that “a continuation of the project would threaten the survival or critical habitat of a newly discovered species of water spider or amoeba.”29 Justice Lewis F. Powell, dissenting. Ibid., 203–04.

Reaction to TVA v. Hill: The 1978 and 1982 ESA Amendments

The decision in Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill caused a political backlash.30Zygmunt J. B. Plater, “Law and the Fourth Estate: Endangered Nature, the Press, and the Dicey Game of Democratic Governance,” Environmental Law 32, no. 1 (Winter 2002): 16. Consequently, Congress im- mediately amended the ESA in 1978. Among other changes, the 1978 amendments defined the critical habitat process, including the requirement that the Services consider economic impacts when designating habitat.31Endangered Species Act Amendments, §§ 2, 11, 92 Stat. 3751, 3766.

The 1978 amendments corrected the ambiguous definition of “critical habitat.” The statutory language, still in effect today, requires the Services “to the maximum extent prudent” to designate critical habitat when it lists a species.32U.S.C. § 1533(a)(3)(A) (2020). When designating critical habitat, the Services are to determine whether the critical habitat was occupied or unoccupied by the listed species.33Ibid., § 1532(5)(A). Occupied critical habitat are those areas containing the species that contain the “physical or biological features essential to the conservation of the species and which may require special management considerations or protection.”34Ibid., § 1532(5)(A). Unoccupied critical habitat are those areas “outside the geographical area occupied by the species” at the time of listing that are “essential for the conservation of the species.”35Ibid., § 1532(5)(A).

With the 1978 amendments, Congress also added economic considerations to the ESA process. Section 4(b)(2) requires the Services to “consider the economic impact, and any other relevant impacts, of specifying any particular area as critical habitat.”36Endangered Species Act Amendments, § 4(b)(2), 92 Stat. 3766. After reviewing these impacts, the Services can “exclude any such area from the critical habitat if [the agency] determines that the benefits of such exclusion outweigh the benefits” of designating the area critical habitat.37U.S.C. § 1533(b)(2) (2020).

The 1978 amendments also made changes to the section 7 consultation requirements. Federal agencies are still required to consult with the Services and ensure “that any action authorized, funded, or carried out” by an agency will not jeopardize the continued existence of a species or result “in the destruction or adverse modification” of the critical habitat of that species.38Ibid., § 1536(a)(2). But the 1978 amendments authorized the Services to allow projects that may affect the species or its habitat to continue if there are “reasonable and prudent alternatives” that minimize adverse impacts.39Ibid., § 1536(b)(3)(A).

If no reasonable or prudent alternatives are available, the 1978 amendments allow a federal agency or permit applicant to apply for an exemption from an “Endangered Species Committee.”40Ibid., § 1536(e)–(h). This seven-member committee, known colloquially as the “God Squad,”41Jared des Rosiers, “The Exemption Process Under the Endangered Species Act: How the ‘God Squad’ Works and Why,” Notre Dame Law Review 66 (1991): 843–45. is made up of mostly cabinet members.42U.S.C. § 1536(e)(3) (2020). Five members of the committee can allow a project to move forward regardless of the impact to a species or its critical habitat.43Ibid., § 1536(h).

The legislative history of the 1978 amendments shows Congress’s concern about the Tennessee Valley Authority decision. In explaining the changes made to the critical habitat sections of the ESA, the House committee report states that the court’s interpretation of the ESA gave “the continued existence of endangered species priority over the primary missions of federal agencies.”44House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, Endangered Species Act Amendments of 1978: Report (to accompany H.R. 14104), H.R. Rep. No. 95-1625, at 10 (1978). Amendments were therefore needed- ed to add flexibility to the critical habitat designation process.45Ibid., 13.

In 1982, Congress further amended the ESA. The 1982 amendments added language stating that listing determinations should be made “solely on the basis of the best scientific and commercial data available” to the agencies.46Endangered Species Act Amendments of 1982, Pub. L. No. 97–304, 96 Stat. 1411 (1982). Economic impacts are not to be a deciding factor in whether the secretary listed a species as endangered or threatened. Instead, economic impacts are to be considered in the “concurrent” designation of critical habitat.4716 U.S.C. §§ 1533(a)(3)(A)(i), (b)(2) (2020).

The House report on the 1982 amendments provides further explanation about the 1978 and 1982 amendments’ purpose and effect.48House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, Endangered Species Act Amendments (to accompany H.R. 6133), H.R. Rep. No. 97- 567 (1982). While the decision to list will be based on biological information, “the critical habitat designation, which is to accompany the species listing to the maximum extent prudent, also takes into account the economic impacts of listing such habitat as critical.”49Ibid., 12. In other words, “the critical habitat designation, with its attendant economic analysis, offers some counter-point to the listing of species without due consideration for the effects on land use and other development interests.”50Ibid.

With both the 1978 and 1982 amendments, Congress wanted to “increase the flexibility in balancing species protection and conservation with development projects.”51Ibid., 10. A key way the amendment balances conservation and economic considerations is section 4(b)(2)’s exclusion process.52Ibid., 12. It requires the Services to weigh the costs and benefits of designating an area as critical habitat and allows them to exclude areas from a designation.53U.S.C. § 1533(b)(2) (2020). But the agencies in charge of implementing the ESA cannot properly conduct that balancing unless they know all the relevant costs. Since the passage of the 1978 and 1982 amendments, the two agencies have viewed critical habitat as playing a limited role in the conservation process. As a result, they often determine that a critical habitat designation imposes few costs and provides few benefits.

The Services’ Approach to Analyzing Economic Impacts

Following the adoption of the 1978 and 1982 amendments, the Services did not frequently designate critical habitat. Early on, they made some effort at complying with the requirement but then quickly changed course.54US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Critical Habitat for the Northern Spotted Owl, 57 Fed. Reg. 10 ( January 15, 1992). They took the position that critical habitat designations are “unhelpful, duplicative, and unnecessary.”55New Mexico Cattle Growers Association v. US Fish and Wildlife Service, 248 F.3d 1277, 1283 (10th Cir. 2001). The Services believed that listing a species provided all the necessary protections to preserve those species.56Ibid. To some extent, the Services still see critical habitat as playing a limited regulatory role (US Fish and Wildlife Service, 84 Fed. Reg. 166, 45044.)

The Services’ belief that critical habitat was unnecessary resulted in them rarely designating critical habitat. Between April 1996 and July 1999, for example, the Fish and Wildlife Service only designated critical habitat for 2 of 256 species listed during that period.57Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, Amendments to the Critical Habitat Requirements of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (to accompany S. 1100), S. Rep. No. 106-126, at 2 (1999). The agency routinely put off designating critical habitat until ordered by a court to do so.58Ibid.

The Services’ view of critical habitat designations as superfluous affected their analysis of the economic impacts of critical habitat designation. When the agencies did designate critical habitat, they used an “incremental baseline approach” to study the costs.59 New Mexico Cattle Growers Association, 1280. This approach viewed any impacts not solely attributable to critical habitat designation as “baseline” impacts of listing the species.60Ibid. The Services then attributed any impacts above those baseline impacts to the critical habitat designation. But because the agencies viewed the listing as the key event, and the designation of critical habitat as unimportant, the Services would nearly always conclude that the designation of critical habitat resulted in no impacts.61Ibid., 1285.

In 1999, several New Mexico farming and ranching organizations challenged this interpretation of the ESA’s economic impact requirement.62Ibid., 1283. The organizations argued that some costs of listing are “coextensive” with the costs of critical habitat, and that (in this case) the Fish and Wildlife Service should include these costs in their economic analysis.63Ibid., 1282–84. Under this approach, the agency would have to consider all the impacts of designating critical habitat, even if those costs could also be attributed to other factors such as the listing of the species.

The 10th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the farmers and ranchers, and held that the Services would have to use the “coextensive” approach when analyzing economic impacts. The court stated that the agencies’ interpretation of the ESA’s economic impact requirement made it “virtually meaningless.”64Ibid., 1285. Because Congress would not have implemented a meaningless requirement, the court reasoned, Congress must have intended for the Services to measure the coextensive costs of designating critical habitat.65 Ibid.

In the years following New Mexico Cattle Growers Association, the Services slightly changed their opinion on the role of critical habitat. Before, the Services believed that critical habitat designations were duplicative of the listing process. After a few lawsuits, most notably Gifford Pinchot Task Force v. US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Services changed position.66Gifford Pinchot Task Force v. US Fish and Wildlife Service, 378 F.3d 1059, 1070 (9th Cir. 2004). In Gifford Pinchot, the Ninth Circuit ruled unlawful the agencies’ interpretation that critical habitat was duplicative and unnecessary.67Ibid.

Following Gifford Pinchot, the Services still maintained that critical habitat is duplicative of listing for protection of a species. Their new interpretation, however, stated that critical habitat can play a limited role in species recovery that could not be achieved through the listing process.68 US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Revisions to the Regulations for Impact Analyses of Critical Habitat, 78 Fed. Reg. 167 (August 28, 2013); US Fish and Wildlife Service, Policy Regarding Implementation of Section 4(b)(2) of the Endangered Species Act, 81 Fed. Reg. 28 (Feb. 11, 2016). Therefore, in some cases, a critical habitat designation will impose economic impacts if it helps the recovery (as opposed to merely the preservation) of the species.

In 2010, the Ninth Circuit endorsed the incremental baseline approach in Arizona Cattle Growers’ Association v. Salazar.69Arizona Cattle Growers’ Association v. Salazar, 606 F.3d 1160 (9th Cir. 2010). Based on the Services’ new approach to critical habitat following Gifford Pinchot, the court stated that the 10th Circuit’s concerns about the economic impact requirement being meaningless are no longer valid70Ibid., 1172–73. because, in at least some cases, designating critical habitat will impose costs independent of listing.71Ibid., 1173. Thus, instances where critical habitat is used to help species recovery are what matter for the purposes of determining whether to exclude an area from the designation.

The Ninth Circuit’s decision in Arizona Cattle Growers’ Association allowed the Services to continue using the baseline approach when analyzing the economic impacts of a critical habitat designation. In 2013, the Services formally adopted the approach by promulgating a regulation.72US Fish and Wildlife Service, 78 Fed. Reg. 167, 53062. Since then, landowners and other stakeholders have filed a few lawsuits to require the Services to follow the coextensive approach. In most of these cases, courts have deferred to the agencies’ interpretation of the ESA, holding that the incremental approach is proper.73Cape Hatteras Access Preservation Alliance v. US Department of the Interior, 344 F. Supp. 2d 108, 130 (D.D.C. 2004); Fisher v. Salazar, 656 F. Supp. 2d 1357, 1373 (N.D. Fla. 2009). The 10th Circuit has not addressed the issue since the Services adopted the regulation, although lower federal courts in Colorado and New Mexico, which are within the 10th Circuit, sided with the Fish and Wildlife Service in recent lawsuits.74Colorado v. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, 362 F. Supp. 3d 951, 988 (D. Colo. 2018); Northern New Mexico Stockman’s Association v. US Fish and Wildlife Service, CIV 18-1138 JB\JFR (D. N.M. 2020). Pacific Legal Foundation represents the two plaintiff ranching organizations in the latter lawsuit, which challenges the critical habitat designation for the New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse.

In September 2019, the Services altered their interpretation of the 1982 amendments.75US Fish and Wildlife Service, 84 Fed. Reg. 166, 45020. Before 2019, the Services’ regulations stated that the agencies must determine endangered status “solely on the basis of the best available scientific and commercial information regarding a species’ status, without reference to possible economic or other impacts of such determination.”76“Factors for listing, delisting, or reclassifying species.” 50 C.F.R. §424.11(b) (2020). The new rule removes the phrase “without reference to possible economic or other impacts” from the regulation.77US Fish and Wildlife Service, 84 Fed. Reg. 166, 45020. It also allows the Services to reference economic impacts when listing a species as threatened or endangered, although the Services are still prohibited from declining to list a species because of those economic consequences.78Ibid., 45024.

The 2019 rule may be a substantial change in position for the Services. Previously, the Services strictly interpreted the 1982 amendments as preventing the Services from conducting any analysis of the costs and benefits of listing a species.79US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Preparation of Environmental Assessments for Listing Actions under the Endangered Species Act, 48 Fed. Reg. 207 (October 25, 1983). This interpretation of the 1982 amendments was one justification for rejecting the coextensive approach.80Arizona Cattle Growers’ Ass’n., 1173. This interpretation also resulted in the Services’ rejection of the requirements of statutes and executive orders that require agencies to measure the costs and benefits of regulations.81US Fish and Wildlife Service, 48 Fed. Reg. 207, 49245.

The 2019 rule recognizes those statutes and executive orders that require agencies to measure the costs of their actions.82US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Revision of the Regulations for Listing Species and Designating Critical Habitat, 83 Fed. Reg. 143 ( July 25, 2018). While the Services cannot refuse to list an endangered or threatened species because of economic impacts, the agencies can still inform the public about those impacts.83US Fish and Wildlife Service, 84 Fed. Reg. 166 (August 27, 2019). The new rule, however, does not require the Services to analyze the costs of listing a species. At most, the new rule merely encourages the Services to measure these costs.

Even if the agencies start providing information about the economic impacts of listing decisions, it is unlikely that the Services will change course on the baseline approach to analyzing the economic impacts of critical habitat designation. Even if the Services know the costs of listing, the regulation defining “economic impacts” for critical habitat remains unchanged. The only ways to guarantee a change in policy are through litigation that challenges the incremental approach as unlawful, through a change in the Services’ regulations interpreting “economic impacts,” or through Congress amending the Endangered Species Act.

Measuring the Costs of Critical Habitat Designation

The Services should reconsider their approach to analyzing the economic impacts of critical habitat designation. Since the passage of the ESA, the Services have downplayed the role critical habitat plays in the endangered species process. The Services’ view that critical habitat has limited benefits also means that, per the agencies, critical habitat has limited costs, because they seem to believe designation has a limited impact overall on private property.

Currently the Services view listing and critical habitat designation as completely separate actions that have separate costs.84US Fish and Wildlife Service, 78 Fed. Reg. 167, 53067. Under the Services’ view, the costs of listing are primarily the opportunity costs associated with avoiding a “take” of the species.85US Fish and Wildlife Service, 57 Fed. Reg. 10, 1811. This estimates the costs from reduction of timber harvest as a result of the listing of the northern spotted owl. Projects and development may need to be altered or abandoned in order to avoid liability for harming a species. As stated earlier, until recently the Services’ regulations discouraged the agencies from measuring the costs of listing a species.

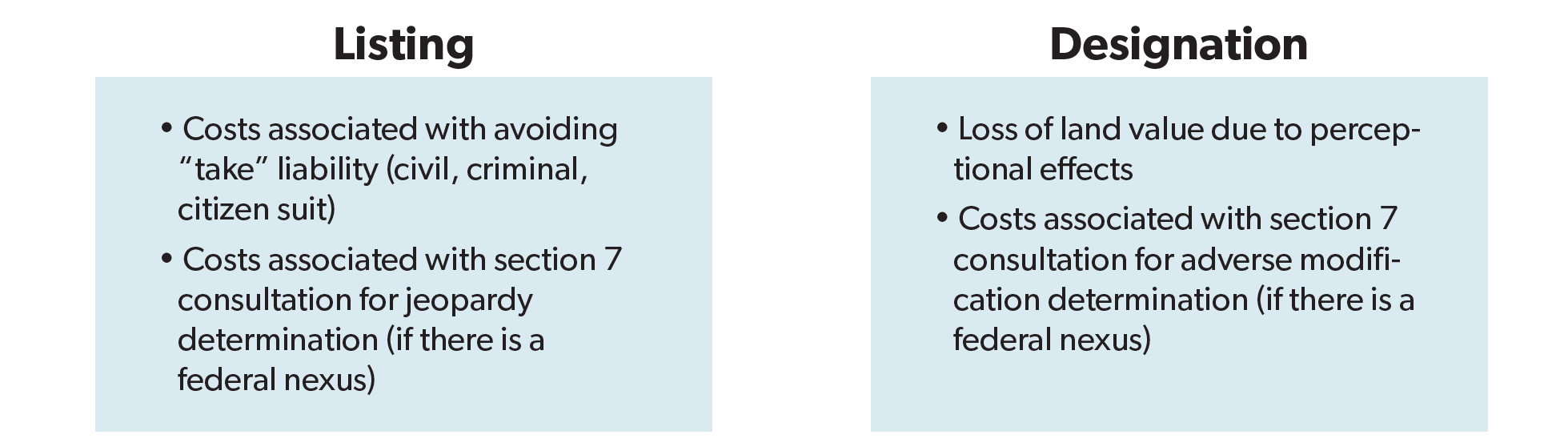

Figure 1. How the Services Currently Categorize the Costs of ESA Decisions

According to the Services, the primary cost of critical habitat designation comes from section 7 of the ESA.86US Fish and Wildlife Service, “Critical Habitat under the Endangered Species Act,” last modified June 13, 2017, https://www.fws.gov/southeast/endangered-species-act/critical-habitat/. Because section 7 only regulates federal agencies, the Services have often argued that a critical habitat designation does not affect private landowners.87When analyzing the economic impacts for the proposed critical habitat of the Florida bonneted bat, the Service recognized that section 7 consultation imposes costs but stated, “However, some activities on State, County, private, or other lands may not have a Federal nexus and, therefore, may not be subject to section 7 consultations.” US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for Florida Bonneted Bat, 85 Fed. Reg.112 ( June 10, 2020). According to them, unless a landowner needs a federal permit, the land lacks a “federal nexus” and the landowner does not need to worry about section 7 consultation. Thus, the Services argue, the ESA primarily imposes costs on private landowners through the listing process, not the critical habitat designation process. The only potential costs to private landowners come from other people’s perceptions about the value of land that is designated critical habitat.88US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for the Georgetown and Salado Salamanders, 85 Fed. Reg. 179 (September 15, 2020). The Services usually view these “perceptional effect” costs as minor.89Ibid.

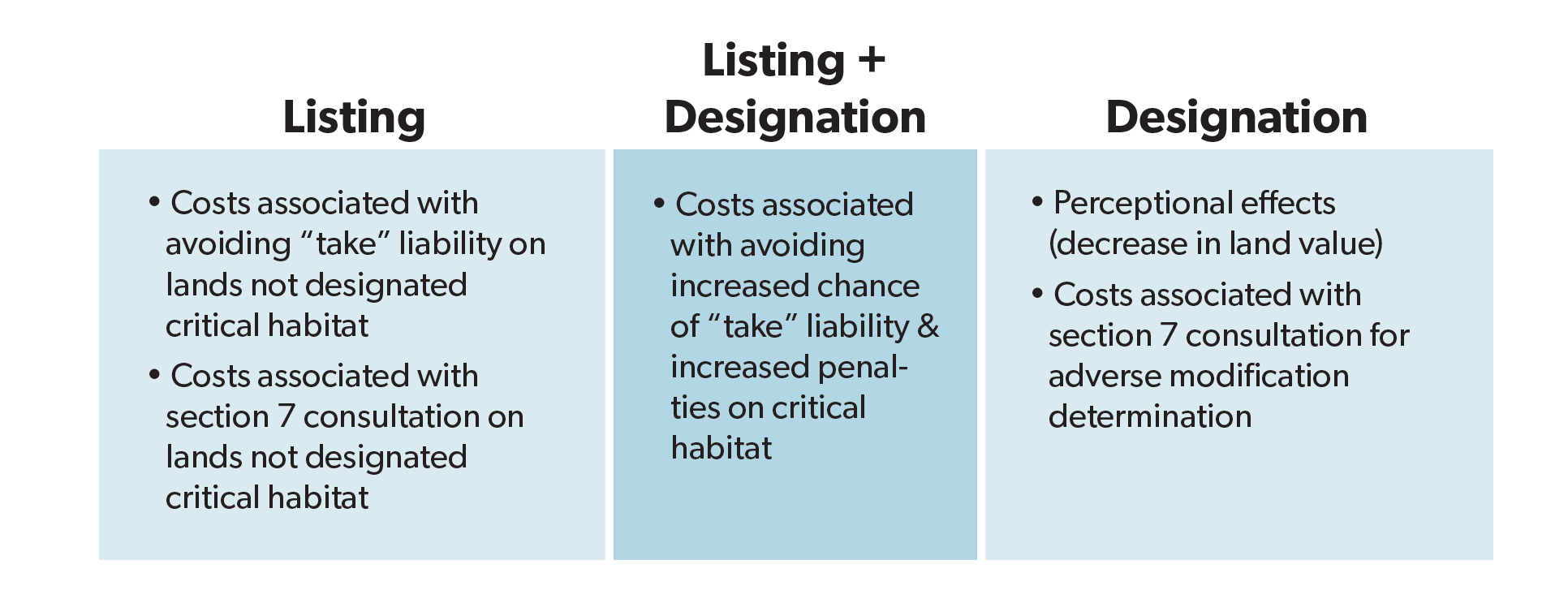

The Services’ current approach, as illustrated in figure 1, does not fully capture how a critical habitat designation affects private landowners. Sometimes the effects of listing a species are not realized until land is designated critical habitat.9090 Jonathan Wood, “Why Do Property Owners Care about Critical Habitat?,” FREEcology Blog, December 16, 2016, https://libertarianenvironmentalism.com/2016/12/16/critical-habitat/. A coextensive approach to measuring economic impacts, as illustrated in figure 2, would measure not just those costs solely attributable to designating critical habitat, but also those instances where the costs of critical habitat overlap with the costs of listing.

The Services should adopt the coextensive approach for two reasons. First, the coextensive approach is more closely aligned with the language and purpose of the 1978 and 1982 amendments to the ESA. In passing those amendments, Congress intended for the listing and critical habitat designation to happen concurrently and expressed an intent for the Services to analyze the economic impacts of decisions under the ESA. Although the 1982 amendments to the ESA clarify that economic impacts cannot factor into the listing decision, Congress still wanted as much economic information as possible about the Services’ actions. A coextensive approach to analyzing economic impacts reflects congressional intent.

Second, the coextensive approach better measures the marginal impacts of critical habitat designation. Although the Services state that they intend to study the “incremental” costs of designating critical habitat, in practice their strict approach to evaluating costs underestimates the marginal costs of designating critical habitat.91US Fish and Wildlife Service, 78 Fed. Reg. 167, 53062. By labeling costs as either “costs of listing” or “costs of designating critical habitat,” the Services leave out instances where the costs of listing are imposed on landowners because of the critical habitat designation.92Ibid.

Figure 2. Coextensive Approach to Categorizing Costs of ESA Decisions

But even if the Services continue the current approach of separating the costs of listing and the costs of designating critical habitat, they can improve the way they measure the impacts of critical habitat. The Services recognize that public perception of designated property can decrease the value of that property. However, the Services often fail to quantify these perceptional effects. Often, the Services cite a lack of data for the inability to quantify how critical habitat affects property values. Currently, there are only a few independent studies that study the impacts of critical habitat. More research can help the Service and the public better understand the impacts of designating critical habitat.

The Services Should Measure the Coextensive Costs of Designating Critical Habitat

The Services should include coextensive costs of listing when examining the costs of a critical habitat designation. The language and legislative history of the 1978 and 1982 amendments indicate that Congress wanted the Services to consider these costs when designating critical habitat. As stated earlier, Congress passed the 1978 amendments in response to Tennessee Valley Authority. The legislative history shows that Congress wanted the Services to have flexibility to balance the costs and benefits of designating critical habitat. More information will allow the Services to better achieve that goal.

Congress anticipated that the Services would designate critical habitat at the same time they listed a species.93House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, Endangered Species Act Amendments (to accompany H.R. 6133), H.R. Rep. No. 97- 567, at 12 (1982). In a congressional hearing about the proposed 1978 amendments, the Director of the Fish and Wildlife Service testified that the agency “adopted the policy of trying to designate critical habitat at the same time we list the species, so everyone knows what is at stake.” 94 Endangered Species: Hearings Before the House Subcommittee on Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation and the Environment of the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, 95th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1978), 2:868. Therefore, in adopting the 1978 amendments, Congress likely anticipated that the Services would approach the decision to list and designate critical habitat coextensively. In doing so, the agencies would not separate the economic impacts of the decision.

And as the Services recently recognized, the 1982 amendments do not prevent the agencies from measuring the economic impacts of listing. The 2019 rule acknowledges that studying the economic impacts of listing “more closely align[s] the regulatory language to the statutory language” of the ESA.95US Fish and Wildlife Service, 84 Fed. Reg. 166, 45026. Congress wanted the Services to provide this information, so long as they did not use it to determine whether a species is endangered or threatened.96Ibid. In other words, the 1982 amendments were passed ‘‘to prevent [critical habitat] designation from influencing the [listing] decision.”97House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, Endangered Species Act Amendments (to accompany H.R. 6133), H.R. Rep. No. 97- 567, at 12 (1982).

There are good reasons to measure the costs of listing, independent of any role those costs play in designating critical habitat. The 2019 rule acknowledges the value of knowing the costs of listing a species.98US Fish and Wildlife Service, 84 Fed. Reg. 166, 45025. Even if those costs cannot affect whether a species is listed, it can inform the public and policymakers about the impact of the Endangered Species Act.99Ibid. The Services stated, “Some members of the public and Congress have become increasingly interested in better understanding the impacts of regulations including listing decisions.” This information can allow Congress to respond whenever necessary.

Therefore, even if measuring the coextensive costs of critical habitat provides no insight about the marginal costs of designation, it still makes sense from a legal and public policy perspective. After the Supreme Court’s decision in Tennessee Valley Authority, Congress was concerned with the economic impacts of endangered species regulations generally. Although Congress restricted the Services from making listing determinations based on the costs of listing, it still wanted the Services to provide that information.

Measuring Coextensive Costs Better Measures the Marginal Impact

Measuring the coextensive costs of designating critical habitat, however, does make sense from an economic perspective because designating critical habitat can increase the marginal costs for landowners. Often, the costs of listing cannot be separated from the costs of designating critical habitat because designating critical habitat increases the likelihood and potential penalties for violating the ESA’s take provision.

The Service’s current approach to analyzing economic impacts fails to capture these costs. Unfortunately, few independent studies have tried to measure these impacts either. In order to better understand how critical habitat affects private landowners, researchers should study how private landowners react to critical habitat designations.

In many cases, the costs of listing and the costs of designating critical habitat cannot be separated. Although the Services state that their goal is to measure the incremental costs of designating critical habitat, the approach of separating costs of listing from costs of designation leaves out some of the marginal costs of a designation. In at least some cases, the costs of listing a species cannot be separated from the costs of designating critical habitat because the two decisions together impose costs on landowners.

The baseline approach only measures impacts solely attributable to the critical habitat designation.100US Fish and Wildlife Service, 85 Fed. Reg. 112, 35532–33. This approach does not allow the Services or the public to get a full picture of how critical habitat impacts private landowners. In order to accurately measure the marginal impacts of designating critical habitat, the Services should measure the coextensive costs of designating critical habitat.

For example, designating land as critical habitat imposes costs of listing onto those landowners. This is especially true when the Services designate land as occupied critical habitat. Designating land as occupied critical habitat signals that the species is prevalent in the area, and it reflects the Services’ determination of the importance of that habitat. Thus, individuals, organizations, and governmental entities often act as if the species is in the entirety of the critical habitat.

One way the costs of listing are linked with the costs of critical habitat is through the ESA’s take provision. The ESA makes it a crime to “knowingly” harm endangered species and some threatened species.10116 U.S.C. §§ 1540(a)(1), 1540(b)(1), 1533(d) (2020). The statute also authorizes the Services to impose civil penalties for those that take species, with the penalties being more severe for knowing violations.102Ibid., § 1540 The Services interpret “harm” to mean any act that “ac- tually kills or injures wildlife,” including “significant habitat modification or degradation where it actually kills or injures wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns, including breeding, feeding or sheltering.”103“Definitions,” 50 C.F.R. § 17.3 (2020).

A critical habitat designation increases the risk that a landowner will violate the take provision of the ESA.104See Kimberly L. Mayhew “United States v. Wang Lin Company: The Kangaroo Rat and Criminal Prosecution under the Endangered Species Act,” San Joaquin Agricultural Law Review 6 (1996): 193, 213. Under the Supreme Court’s decision in Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapter of Communities for a Great Oregon, 515 U.S. 687, 691 (1995), the government can prove an ESA violation solely by demonstrating habitat modification. By labeling habitat as “critical,” it is more likely that any modification of that habitat will be “significant,” given how critical habitat is defined in relation to species’ “essential” habitat needs.105University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center, “Do I have Critical Habitat on My Land?,” accessed November 6, 2020, https://wrrc.arizona.edu/gila/do-i-have-critical-habitat-my-land. “[C]ritical habitat designation may indicate that a species protected by the ESA may reside on your property. If this is the case, any land modification, which adversely affects the listed species could qualify as a ‘take’ of that species.” Indeed, while the ESA requires the Services to designate critical habitat concurrently with a listing, they have adopted regulations that allow them to delay a critical habitat designation if potential destruction or modification of the habitat “is not a threat to the species.”106“Criteria for designating critical habitat,” 50 C.F.R. § 424.12 (2020).

An occupied critical habitat designation can also increase the risk of liability for the non-habitat-modification take. For example, the Services define “harass” as “an intentional or negligent act or omission which creates the likelihood of injury to wildlife by annoying it to such an extent as to significantly disrupt normal behavioral patterns.”107“Definitions,” 50 C.F.R. § 17.3 (2020). One is more likely to harass a species if the species is present. And if the Services state that land is “occupied” by a species, landowners are more likely to take a conservative approach toward land use in order to avoid take liability.

A critical habitat designation also makes it easier for the Services to prove that a landowner “knowingly” violated the take provision.108 For an overview of how courts have interpreted the “knowingly” requirement, see Jonathan Wood, “Overcriminalization and the Endangered Species Act: Mens Rea and Criminal Convictions for Take,” Environmental Law Reporter 46, no. 6 ( June 2016): 10496. A critical habitat designation puts landowners on notice about the importance of the habitat and that the species is present (at least in the agencies’ estimation). People who knowingly violate the take provision face more severe penalties. Furthermore, when assessing penalties, a court may view someone as more culpable for a take after critical habitat is designated.109The Services will request greater penalties depending on one’s culpability in violating the ESA. See NOAA Office of General Counsel, “NOAA Policy for Assessment of Penalties and Permit Sanctions 29,” June 24, 2019, https://www.gc.noaa.gov/documents/Penalty-Policy-CLEAN-June242019.pdf.

While the Services include the range of a species upon listing it, there are important differences between the range of a species and its critical habitat. The range is “generally delineated around species’ occurrences” and may include areas used by a species only periodically.110“Definitions,” 50 C.F.R. § 424.02 (2020). Occupied critical habitat, on the other hand, comprises areas that are “essential to the conservation of the species” and “may require special management considerations or protection.”11116 U.S.C. § 1532(5)(A) (2020).

Furthermore, before the Services can label critical habitat occupied, the agencies must have substantial evidence that the species uses the area with sufficient regularity that it is likely present during any reasonable span of time.112New Mexico Farm and Livestock Bureau v. United States Department of the Interior, 952 F.3d 1216, 1226 (10th Cir. 2020); Ariz. Cattle Growers’ Ass’n., 1165. Pacific Legal Foundation represented several agricultural organizations in New Mexico Farm and Livestock Bureau. No such evidence is required to determine the range of a species. A critical habitat designation sends a strong signal to landowners, regulators, and other interested parties that the species is regularly present in the areas.

Therefore, the regulatory costs of a listing may not be actualized until the designation of critical habitat. Although the potential penalties for violating a take are technically costs associated with listing, the critical habitat designation increases the likelihood that those costs will be imposed on landowners. A critical habitat designation puts landowners and regulators on notice that the listed species is purportedly in that area. It focuses regulatory action on specific areas.113As stated earlier, occupied critical habitat “may require special management considerations or protection.” 16 U.S.C. § 1532(5)(A). A critical habitat designation also allows those interested in bringing citizen suits to focus their attention on activities that occur in designated critical habitat.

A recent critical habitat designation in Alabama shows how the costs of listing can be imposed on landowners through a critical habitat designation.114Pacific Legal Foundation is representing landowners and the Forest Landowners Association in a lawsuit against the Service over the designation of the black pine snake critical habitat designation. In 2015, the Service listed the black pine snake as a threatened species.115115 US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Species Status for Black Pine Snake with 4(d) Rule, 80 Fed. Reg. 193 (October 6, 2015). In February 2020, the Fish and Wildlife Service designated 324,679 acres of land in eight units in Mississippi and Alabama as occupied critical habitat for the pine snake, including 93,208 acres of private property.116US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for Black Pine Snake, 85 Fed. Reg. 38 (February 26, 2020).

By designating the area as “occupied” critical habitat, the Service imposed the costs of listing on the private property. Landowners responded to the designation by changing their behavior to avoid the increased liability that results from a critical habitat designation. As one timber organization noted in its comment against the designation, “with that designation comes the presumption that black pine snake populations are present.”117Gary Skipper, Southern Timberlands Alliance, “Comments on the Proposed Listing of Black Pinesnake (Pituophis melanoleucus lodingi) as a Threatened Species Pursuant to the Endangered Species Act, Associated 4(d) Rule, Critical Habitat, and Draft Economic Analysis” (Comment on FWS-R4-ES-2014-0046, May 11, 2015), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FWS-R4-ES-2014-0065-0133. But because the Service viewed the costs of avoiding take as baseline costs, it did not measure these costs when deciding what areas to exclude from the critical habitat designation.118US Fish and Wildlife Service, 85 Fed. Reg. 38, 11241–42.

Measuring the coextensive impacts of critical habitat can assist the services in setting appropriate boundaries for critical habitat designations. Additionally, the coextensive approach to measuring eco- nomic impacts can help the Services determine the appropriate boundaries of a critical habitat unit. The ESA’s economic analysis requirement directs the Services to weigh the costs and benefits of designating an area as critical habitat, and to authorize the exclusion of areas that they view as too costly. The baseline approach often fails to give the Services a full picture of the impacts of the designation.

For example, with the black pine snake designation, the baseline approach may have resulted in an excessive critical habitat designation. Over one-third of the private land falls within two units of critical habitat.119Ibid., 11268–69. Unit 7 of the designation consists of 33,395 acres of privately held forestland previously leased under Alabama’s Wildlife Management Area program. Unit 8 consists of 5,943 acres of land, of which 2,100 acres are privately owned.

In determining that the snake occupied Unit 7, the Service pointed to five sightings of the snake since 1994.120Ibid., 11254. To justify its designation of Unit 8 as occupied, the Service relied on two snake sightings since 1992.121Ibid., 11254. Public comments and peer reviewers criticized the Service’s methodology and determination that these lands are occupied by the snake.122 Mike Duran, “Peer Review of USFWS Proposal to Designate Critical Habitat for the Black Pinesnake” (Comment on FWS–R4–ES–2014– 0065, May 10, 2015), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FWS-R4-ES-2014-0065-0144; Gary Skipper, “Comments on the Proposed Listing of Black Pinesnake,” 12–14.

Despite few sightings and the small range of an individual snake, the Service labeled tens of thousands of acres as occupied critical habitat.123US Fish and Wildlife Service, 85 Fed. Reg. 38, 11239. The average home range area for an individual snake is between 106 acres, the median for an adult female, and 979 acres, the maximum ever recorded for an adult male (11248). If the Service had included coextensive costs in its analysis, there would have been greater political pressure on the Service to ensure that the size and location of the units were accurate because the public provides more scrutiny of costly regulations.124The Fish and Wildlife Service has recently proposed a rule that would lead to more exclusions when the costs of a designation outweigh the benefits, which reflects at least some political pressure to ensure that designations minimize costs. US Fish and Wildlife, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Regulations for Designation Critical Habitat, 85 Fed. Reg. 274 (September 8, 2020). Pacific Legal Foundation has submitted comments on behalf of itself and some of its clients in support of the proposed rule. If, after taking a closer look, the Service discovered that the critical habitat was unoccupied and not “essential for the conservation of the species,”12516 U.S.C. § 1532(5)(A). it could have excluded portions of the area from the designation. The baseline approach, however, foreclosed those possibilities.

There are few empirical studies looking at the coextensive costs of critical habitat designation. There are few empirical studies that look at the coextensive costs of critical habitat, but one recent study shows some link between listing costs and habitat designation.126Richard T. Melstrom, Kangil Lee, and Jacob P. Byl, “Do Regulations to Protect Endangered Species on Private Lands Affect Local Employment? Evidence from the Listing of the Lesser Prairie Chicken,” Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 43, no. 3 (2018): 346–63. In 2018, several professors studied how the listing of the lesser prairie chicken affected employment in counties with the chicken’s habitat. Prior to the listing in 2014, several states worked with the Fish and Wildlife Service to develop a conservation program that “offsets habitat losses with new habitat brokered through voluntary land use agreements.”127Ibid., 340. Many landowners and private companies expected the Service not to list the chicken as a result of the conservation program, but the Service eventually did so anyway. A federal court vacated the listing in 2015.128Permian Basin Petroleum Association v. US Department of the Interior, 127 F. Supp. 3d 700 (W.D. Tex. 2015). In fact, it was the Service’s unlawful application of rules related to the conservation plans that resulted in the court vacating the listing (722–74). In an unrelated case, Pacific Legal Foundation is representing an association of counties in western Kansas that participate in another lesser prairie chicken conservation plan. Kansas National Resources Coalition v. US Department of the Interior, 382 F. Supp. 3d 1179 (D. Kan. 2019).

The authors examined the effect of the brief listing on employment rates in the counties with lesser prairie chicken habitat.129 Melstrom, Lee, and Byl, “Lesser Prairie Chicken,” 348. They concluded that employment in those counties declined proportionally with the amount of habitat in those counties.130Ibid., 359. They also found some evidence that pre-listing conservation actions affected employment as well.131Ibid., 358. Although the Service never designated any of the land as critical habitat, the study shows that the costs of listing and the costs of habitat determinations are intertwined; when an area is labeled as habitat, that label announces to the public the presence of the species and thus triggers associated burdens.

Unfortunately, few other studies take a similar approach to measuring the costs of critical habitat designation. More independent research can help establish whether some costs of designation are coextensive with the costs of listing and whether designation imposes listing costs on landowners.

The services should reconsider their approach to measuring the economic impacts of critical habitat. With the 1978 amendments to the ESA, Congress intended for the Services to provide a full picture of how species’ legal protections affect individuals. The ESA’s economic impact analysis requires that impacts of listing be considered along with the impacts of designation. And while these costs cannot be used to prevent listing a species, they still provide valuable information about the costs of designating critical habitat.

The agencies’ 2019 rule allows the Services to assess the economic impacts of listing. But it is still too early to tell what effects, if any, this new rule will have on how the Services assess economic impacts for critical habitat. The new rule only authorizes the Services to analyze the economic impact of listing; it does not require it. It is possible that the Services will fail to provide any information on the costs of listing, even though the agencies’ policy now allows for such an analysis.

Even if the Services take an aggressive approach to evaluating the impacts of listing, it is uncertain whether the Services will incorporate those impacts into the critical habitat assessment. If the Services want to downplay the economic impacts of a critical habitat designation, they can continue to adhere to the baseline approach and completely separate the costs of listing and costs of designation. The most recent critical habitat designations still rely on economic analyses produced before the new rule.132US Fish and Wildlife Service, 85 Fed. Reg. 112, 35532. It will likely be several years before we will know what role, if any, the costs of listing play in the ESA process.

The Services Can More Accurately Assess the Costs of Designating Critical Habitat

Even if the Services continue to strictly apply the baseline approach to measuring economic impacts, they can improve how they measure the impacts of designating critical habitat. As discussed earlier, the Services state that critical habitat designation has a “limited regulatory role” in conserving endangered species.133US Fish and Wildlife Service, 84 Fed. Reg. 166, 45044. As a result, the Services view the main costs of a critical habitat designation as increased costs from section 7 consultation. However, those costs will only occur when a project has a federal nexus (i.e., when a project receives federal funds or requires a federal permit).134US Fish and Wildlife Service, “Critical Habitat under the Endangered Species Act,” last modified June 13, 2017, https://www.fws.gov/southeast/endangered-species-act/critical-habitat/. Even without a federal nexus, a critical habitat designation can impose costs on private property owners. The Services have recognized some of these costs, but they sometimes have difficulty quantifying all of the costs. If the Services are unable to fully evaluate the costs of designating critical habitat, independent research can help fill the data gap.

Costs on private landowners even in the absence of a federal nexus. A critical habitat designation can impose costs on private land even without a federal nexus.135Maximililan Auffhammer, Maya Duru, Edward Rubin, and David L. Sunding, “The Economic Impact of Critical-Habitat Designation: Evidence from Vacant-Land Transactions,” Land Economics 96, no. 2 (May 2020): 192. As discussed earlier, critical habitat has a signaling effect for state and local governments, nongovernmental organizations, and individuals.136The Services, 81 Fed. Reg. 28, 7414. In the agencies’ own words, a critical habitat designation “helps focus the conservation efforts of other conservation partners, such as state and local governments, nongovernmental organizations, and individuals.”137Ibid. And “when designation of critical habitat occurs near the time of listing, it provides a form of early conservation planning guidance.”138Ibid.

But this signaling function also comes with cost. If the agencies designate an area “where federal agencies can focus their conservation programs and use their authorities to further the purposes of the Act,”139Ibid. then it is more likely that such an area will be subject to future regulation. In some states, like California, a critical habitat designation can affect the environmental analysis conducted under the state’s environmental quality act.140California Public Utilities Commission, Proponent’s Environmental Assessment West of Devers Upgrade Project, October 2013, 4.4-101, https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/environment/info/aspen/westofdevers/pea/4.04_bio_part2.pdf. These potential issues can decrease the value of the land, even if the landowner never seeks a federal permit.141Auffhammer et al., “Economic Impact,” 191. Yet the Services often do not analyze these costs.

The Services did not always take this approach to the incremental costs of designating critical habitat. For example, the 1992 designation of critical habitat for the northern spotted owl shows the Fish and Wildlife Service’s early approach to analyzing the economic impacts of critical habitat. Although the Service as- sessed baseline costs and benefits before conducting the exclusion analysis, it still measured the estimated $113 million cost of the listing determination.142US Fish and Wildlife Service, 57 Fed. Reg. 10, 1811, 1816. The economic analysis then analyzed the costs solely attributable to the critical habitat designation by estimating the costs to federal, state, and local revenue, and costs related to job loss.143Ibid., 1815–16. But even in this thorough economic impact analysis, the Service concluded that the effects on private land would be minimal because there was no federal nexus.144Ibid., 1818.

In the mid-1990s, the Services effectively stopped designating critical habitat. But even since the agencies renewed the designation process, they have provided little information about the costs of critical habitat designations. Recent critical habitat designations contain limited economic analyses; this is the result of the Services’ view of critical habitat. When one of the agencies designates critical habitat on private land, it assumes that the lack of a federal nexus means that the designation does not impose any incremental costs.145 US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for the Trispot Darter, 85 Fed. Reg. 190 (September 30, 2020).

As discussed earlier, the Services have made references to the perceptional effects of designating critical habit on private land.146 Industrial Economics, Inc., Supplemental Information on Perceptional Effects on Grazing – Critical Habitat Designation for the New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse, January 15, 2014, 1, https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FWS-R2-ES-2013-0014-0097. But while the Services will recognize how designation of critical habitat can affect public perception of the designated property, they often do not quantify the loss of value resulting from the designation.147The economic impact analyses often cite data limitations as the reason the Services cannot quantify these costs. Industrial Economics, Inc., New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse, 8; Industrial Economics, Inc., Screening Analysis of the Likely Economic Impacts of Critical Habitat Designation for the Black Pinesnake, October 22, 2014, 3. Without quantifying the costs, the Services cannot adequately weigh the costs and benefits of excluding an area from a designation.

If the Services are underestimating the costs of critical habitat, those interested in knowing the true costs of critical habitat must look elsewhere. But of the few studies that examine the costs of critical habitat, many rely solely on economic theory or anecdotal accounts.148Auffhammer et al., “Economic Impact,” 192.

There are even fewer empirical studies that look at the impacts after an area has been designated critical habitat. The Services rarely evaluate the past impacts of their designations, even when the agencies review the critical habitat designation. For example, in 2012, the Service revised the critical habitat for the Northern Spotted owl.149US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plaints; Designation of Revised Critical Habitat for the Northern Spotted Owl, 77 Fed. Reg. 233 (December 4, 2012). While the economic analysis referenced the 1992 designation, it did not analyze any data from the original designation.150US Fish and Wildlife Service, Final Economic Analysis of Critical Habitat Designation for the Northern Spotted Owl, November 20, 2012. When discussing the potential impact on market value, the study stated: “As the public becomes aware of the true regulatory burden imposed by critical habitat (e.g., regulation under section 7 of the Act is unlikely), the impact of the designation on property markets may decrease.”151Ibid., 5–21. But the study did not look at what happened after the 1992 designation to see if public perception and market value impact changed in the 20 years following the original designation.

Some or all of the perceptional effects may be attributable to the increased risk of violating the ESA’s take prohibition. In other words, some of the decreased land value from a critical habitat designation may be because landowners will limit the use of the land in order to avoid liability. If that is the case, then the Services would not need to drastically change its approach to analyzing the economic impacts of critical habitat designation because the coextensive costs of a designation would be reflected in costs the Services already view as attributable to the designation. However, if the perceptional effects reflect the increased risk of violating the take provision, then the Services are probably incorrect that a designation’s impact to property markets will decrease over time. Furthermore, if decreased land value reflects increased risk to landowners, that only reinforces the need for concrete data on the impacts of critical habitat on housing markets.

More empirical studies are needed. Independent, empirical studies are important because they can further evaluate the costs of critical habitat designation. Moreover, affected landowners can petition the Services to revise the critical habitat designation based on the new information.152“Petitions,” 50 C.F.R. § 424.14 (2020). But even if a new analysis does not immediately change a designation, the information can shape policymakers’ attitudes about the consequences of their decisions.

Some recent independent studies have analyzed the effects of critical habitat on housing markets.153Jeffrey E. Zabel and Robert W. Paterson, “The Effects of Critical Habitat Designation on Housing Supply: An Analysis of California Housing Construction Activity,” Journal of Regional Science 46, no. 1 (February 2006): 67; Erik J. Nelson, John C. Withey, Derric Pennington, and Joshua J. Lawler, “Identifying the Impacts of Critical Habitat Designation on Land Cover Change,” Resource and Energy Economics 47 (February 2017): 89. A recent study from March 2020 looks at 13,000 housing transactions within or near critical habitats for the red-legged frog and the Bay checkerspot butterfly in California.154Auffhamer et al., “Economic Impact,” 188–89. The authors conclude that the critical habitat designation for the red-legged frog resulted in a 47 percent loss in property value.155Ibid., 205. For the Bay checkerspot butterfly, the authors’ data suggest a 78 percent loss in land value.156Ibid. Needless to say, these costs were not considered by the Fish and Wildlife Service when designating the habitats for these two species.

These types of empirical studies are a first step in better understanding the impacts of critical habitat designation. If policymakers and the public are to make informed judgments about environmental policy, they need to have reliable and valid information. Because the Services routinely underestimate the marginal costs of critical habitat designations, scholars must conduct independent research to provide information about the costs of critical habitat.

Measuring the Benefits of Critical Habitat

The ESA requires the Services to measure economic and other relevant impacts of designating critical habitat.15716 U.S.C. § 1533(b)(2). “Impact” means both the costs and the benefits of the designation. But similar to their cost analyses, the Services’ view of the role of critical habitat means that, in the agencies’ estimation, critical habitat offers few benefits. To the extent the Services discuss benefits, they mostly use abstract terms about the increased value to conservation or other environmental values.158US Fish and Wildlife Service, 85 Fed. Reg. 112, 35513.

Scholars debate whether critical habitat is an effective tool for conserving endangered species. A lot of the debate, however, occurs in legal academia.159Damien M. Schiff, “Judicial Review Endangered: Decisions Not to Exclude Areas from Critical Habitat Should Be Reviewable under the APA,” Environmental Law Reporter 47, no. 10 (April 2017): 10352. Schiff cites law review articles that discuss the impacts of critical habitat (10356 n. 75). As with the costs of critical habitat, there are few studies that attempt to quantify the benefits of a critical habitat designation.160Dave Owen, “Critical Habitat and the Challenge of Regulating Small Harms,” Florida Law Review 64, no. 1 (2012): 145. Of the studies that have been conducted, the conclusions are conflicting.161Ibid.

Some studies have shown a positive correlation between critical habitat designations and species recovery.162Martin F. J. Taylor, Kieran F. Suckling, and Jeffrey J. Rachlinski, “The Effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act: A Quantitative Analysis,” Bioscience 55, no. 4 (April 2005): 360. However, these studies do not explain why the designation, rather than some other variable, is producing the species recovery.163Owen, “Regulating Small Harms,” 45; Joe Kerkvliet and Christian Langpap, “Learning from Endangered and Threatened Species Recovery Programs: A Case Study Using US Endangered Species Act Recovery Scores,” Ecological Economics 63, no. 3 (August 2007): 507. In order to properly measure the benefits of a critical habitat designation, scholars need to control for other variables.164Robert L. Fischman and Lydia Barbash-Riley, “Empirical Environmental Scholarship,” Ecological Law Quarterly 44 (2018): 801. But just as critical habitat can impose the regulatory costs of listing, so too can it extend regulatory benefits.

Again, the Services’ view of the role of critical habitat has resulted in few data about the role of critical habitat. A recent Supreme Court case, however, may change the Services’ approach to comparing the costs and benefits of a critical habitat designation. In the past, the Services’ weighing of costs and benefits has lacked specificity because the Services did not believe their exclusion decisions were reviewable.

In Weyerhaeuser Company v. US Fish and Wildlife Service, several landowners and a timber company sued the Fish and Wildlife Service over its critical habitat designation for the dusky gopher frog.165Weyerhaeuser Company v. US Fish and Wildlife Service, 139 S. Ct. 361, 367 (2018). Among other claims, the landowners challenged the Service’s decision not to exclude their property from the critical habitat designation.166Ibid. The Service argued that the decision to not exclude was entirely within its discretion and could not be challenged.167Ibid., 370. The Supreme Court disagreed and held that the Service must offer a reasoned explanation for its decision.168Ibid., 372 While it ultimately did not decide whether the agency’s explanation was acceptable, the court’s decision allows other landowners to sue over exclusion decisions.

The exclusion decision is just one part of the critical habitat designation process. But before Weyerhaeuser, the Services thought that decisions not to exclude were unreviewable. This may have led them to be less than exhaustive in the whole process, including when analyzing the economic impacts of a designation.169Schiff, “Judicial Review Endangered,” 10365. If the Services make a renewed effort toward the exclusion process, they may begin to provide more accurate information about the costs and benefits of designation.

Conclusion

Congress Rejected a Preservation-at-All-Costs Approach

With the 1978 amendments, Congress introduced economic considerations into the Endangered Species Act. Reacting to Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill’s strict ruling, Congress rejected a conservation-at-any-cost approach. It introduced flexibility in balancing species protection and conservation with development projects.

Congress directed the Services to consider the economic impacts of critical habitat designation. The primary purpose is to help the Services decide whether to exclude areas from a designation. But accurate economic analyses can have broader implications. Knowing the true impacts of critical habitat can help policymakers in minimizing costs and maximizing benefits of endangered species policies.

The Services Could Do More to Provide Accurate Information

The exact costs and benefits of critical habitat are unknown. The Services narrowly interpret the ESA’s requirement to analyze the economic impacts of designating critical habitat. Primarily, the Services separate the costs of their decision into costs of listing and costs of designation. Some of the costs of listing, however, are not imposed until the Services designate critical habitat. The Services should analyze these coextensive costs to better understand the impacts of critical habitat. But even if the Services continue their current approach to analyzing the impacts of critical habitat designations, the Services may be understating the effects of their decisions.

The current legal regime has resulted in limited information from the Services. But some recent changes may lead to the release of more information about the impacts of the Services’ ESA decisions. The Services’ own regulations now allow them to measure the economic impacts of listing a species. Further, the Supreme Court has recently ruled that landowners can challenge the decision not to exclude areas from a critical habitat designation. With more information about the economic impacts of critical habitat designation, as well as more scrutiny of their economic impact decisions, the agencies may change course in the future.

Better Critical Habitat Policy Requires Accurate Information

Not only did Congress reject a preservation-at-all-costs approach, but such an approach may also be counterproductive. Ignoring the costs of an action may lead an agency to avoid considering alternative outcomes that may result in greater net benefits.170Jonathan H. Adler, “Money or Nothing: The Adverse Environmental Consequences of Uncompensated Land Use Controls,” Boston College Law Review 49, no. 2 (2008): 304; Gardner Brown Jr. and Jason F. Shogren, “Economics of the Endangered Species Act,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 12, no. 3 (Summer 1998): 15–16. Further, an at-all-costs approach often leads to hostility between the Services and those affected by the agencies’ decisions.

Many property owners, lawyers, and professors advocate for a more cooperative approach toward preserving habitat.171 Stephen Polasky and Holly Doremus, “When the Truth Hurts: Endangered Species Policy on Private Land with Imperfect Information,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 35, no. 1 ( January 1998): 22; John F. Turner and Jason C. Rylander, “The Private Lands Challenge: Integrating Biodiversity Conservation and Private Property,” in Private Property and the Endangered Species Act: Saving Habitats, Protecting Homes, ed. Jason Shogren, 116 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998); Adler, “Money or Nothing,” 359; Society of American Foresters, “Protecting Endangered Species Habitat on Private Land: A Position Statement of the Society of American Foresters,” October 21, 2013, https://nesaf.org/wp-content/uploads/mesaf-doc-archive/Exec%20Comm/2014%20ExComm%20Minutes/Protecting_Endangered_Species_Habitat_on_Private_Land.pdf; Megan E. Hansen, Sarah M. Bennett, Jennifer Morales, and Rebekah M. Yeagley, “Cooperative Conservation: Determinants of Landowner Engagement in Conserving Endangered Species” (Policy Paper, Center for Growth and Opportunity, Utah State University, Logan, UT, November 2018). While a more cooperative approach may require amending the ESA, some sections of the ESA already allow it. As stated earlier, one of the purposes behind the act was to ensure funding for habitat acquisition and preservation. Compensating landowners for preserving critical habitat can incentivize the preservation of critical habitat. But if landowners are to be adequately compensated, the agencies need to accurately analyze the economic impacts of critical habitat.

Section 10 of the ESA also provides for a cooperative approach to habitat conservation. Added in 1982, section 10 allows landowners to develop habitat conservation plans that detail mitigation measures for future projects.17216 U.S.C. §1539(a)(2)). In return, the Services allow some activities that would otherwise be illegal under the act. The Services have also used the critical habitat exclusion process to incentivize landowners to develop habitat conservation plans.173David J. Hayes, Michael J. Bean, and Martha Williams, “A Modest Role for a Bold Term: ‘Critical Habitat’ under the Endangered Species Act,” Environmental Law Reporter 43, no. 8 (August 2013): 10671–74.

Still, these sections of the ESA may not be enough for effective cooperative conservation. Some scholars have noted that current regulatory tools cannot be categorized as cooperative incentives because those programs “focus primarily on removing disincentives rather than providing outright benefits in exchange for species conservation.”174Lauren K. Ward, Gary T. Green, and Robert L. Izlar, “Family Forest Landowners and the Endangered Species Act: Assessing Potential Incentive Programs,” Journal of Forestry 116, no. 6 (November 2018): 530. If that is true, Congress may need to amend the ESA to allow more cooperative conservation practices. Knowing the true costs and benefits is the first step toward achieving better and more economically efficient conservation methods. But before policymakers can implement policies that minimize costs and maximize benefits, they need to know those costs and benefits.

More Independent Research Is Needed

Much of the debate about critical habitat is a debate about the costs and benefits of habitat designation. To have an accurate debate, the public and regulators need accurate information about the costs and benefits of critical habitat designations. This will allow the Services to make more informed decisions about critical habitat designations.

Knowing the true costs and benefits will help policymakers determine whether they can achieve benefits through more cost-efficient means. The Services’ current approach may not be providing a complete view of the impacts of critical habitat.

Recent regulatory changes and court decisions may alter the Services’ approach to critical habitat designation. But independent research can also help provide accurate and reliable information about the costs and benefits of critical habitat.

Unfortunately, there are few independent studies analyzing the impacts of critical habitat. Studies about the effects of critical habitat on housing are a good first step. But more research is needed on how critical habitat designations affect other markets as well (e.g., employment).

Furthermore, scholars need to conduct research on the coextensive costs of critical habitat designation. Even the independent research has followed the Services’ view that the costs of critical habitat are separate from the costs of listing. More data are needed to discern whether economic impacts of listing are im- posed through a critical habitat designation.

More research will help inform the public and policymakers about the role critical habitat plays in species conservation. Before lawmakers and others can make informed decisions about environmental policy, they must have the correct information. Independent researchers should continue their work to provide reliable information about the costs and benefits of critical habitat. Then policymakers can work with these researchers and other members of the public to adopt policies that balance conservation benefits against the costs to landowners.