The House of Representatives is scheduled to take up two immigration bills this week. The Dream and Promise Act of 2021 would provide a pathway for Dreamers to earn permanent residency. The second, the Farm Workforce Modernization Act of 2021, would expand options for legal entry for agricultural workers. These updates will reduce illegal immigration in the future and maximize the benefits of immigration to the entire country. Both Dreamers and migrant farmworkers are bound up in our inflexible immigration system with no way out.

Dreamers and farmworkers have had several failed attempts at reform in the past. Famously, different versions of reform for Dreamers have been introduced 10 times. For farmworkers, a false start came just last year. In 2020, President Trump started working with California’s Representative Zoe Lofgren on an update to agricultural guest worker policies. However, like the reforms for Dreamers, it didn’t make it across the finish line.

We shouldn’t be content if today’s efforts for Dreamers and farmworkers ends in only more pages of legislative debate. Agricultural communities need the workers that immigration provides to get food from farms to our tables. Dreamers and the communities that they live in need a path that reckons with their unique circumstances. The entire country will benefit from smart immigration reform.

Dreamers and their contributions to the U.S.

Dreamers are those brought to the U.S. as children by their parents. The name comes from the original Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, proposed in 2001. Despite the sympathetic case, the 2001 bill failed as have all other attempts since then.

In 2012, President Obama’s administration unilaterally created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy giving work authorization to those who were brought to the U.S. as children. DACA was never meant to last the nine years that it has survived. When it was created in 2012, it was meant to bide time for a legislative solution.

In the House on March 3, the American Dream and Promise Act of 2021 was introduced. The bill would create a way for Dreamers to earn conditional permanent residency if they pass background checks and graduate from high school, in addition to other requirements. Conditional residency is a kind of two-year trial period. When the two years are over, conditional residents must meet conditions to qualify for a 10-year green card or they become removable from the U.S. In the case of Dreamers, to earn permanent residency, the House bill gives three options:

- Dreamers must complete at least two years of college,

- Dreamers must complete two years of military service, or

- Dreamers must be consistently employed for at least 75 percent of the time when they were authorized to work in the country.

The House bill has some similarities with a bill introduced by Senators Lindsey Graham and Dick Durbin in February of this year. For example, the bill in the Senate creates a similar pathway for permanent residency and requires applicants pass a background check and graduate from high school. Both the House and Senate bills are exciting steps towards a needed legislative fix for Dreamers.

About 600,000 Dreamers across the country need solutions like these today. As many as 800,000 people have been protected through the program since it was created. Dreamers are young, on average 27, and work in a variety of occupations. In early 2020, many pointed out their important role in critical industries. For example, the Center for Migration Studies estimates that 40,000 DACA recipients work in healthcare. That meant many of those protected by DACA were on the front lines treating COVID-19.

Working in essential industries and throughout the economy makes Dreamers an economic boon. With back-of-the-envelope estimates, economists have suggested that they could contribute as much as $133 billion to the U.S. economy. After all, research suggests that 93 percent of recipients are actively working. And that culminates in Dreamers paying about $890 million in federal taxes each year.

Setting aside the economic contributions of Dreamers, the crux of the policy problem is that there isn’t a way for them to regularize their status — current policy doesn’t include a way to become legal residents. Even though many have been in the U.S. since they were just a few years old, DACA does not allow recipients to apply for citizenship or even permanent residency. As political scientist Michelangelo Landgrave explains, “It would be one thing if DACA recipients had to “wait in line” with other migrants, but under DACA there is no line.”

Landgrave also points out that the limitations of the program also “frustrates would-be employers.” For one, DACA requires a two-year timeline for renewal. Notably, this limits educational choices and any form of long-term planning. College degrees are generally four-year programs, and employers want to know that employees are likely to stick around. But the employment problems for DACA go deeper as well.

Due to their unusual legal status in the country, state laws prevent many Dreamers from working in certain occupations. For example, Utah just updated its laws to allow DACA recipients to work as police officers in the state. In 2019, Arkansas finally allowed Dreamers to work as nurses. Today the state is considering extending that policy to teachers as well. These are needed reforms. However, they are still only piecemeal reform efforts. Even though state economies will benefit from taking these state-level reforms, it is still only individual states that are one-by-one allowing Dreamers to work in a handful of licensed occupations.

Real reform that gives DACA holders permanent residency will further boost their contributions to state and local economies by removing these barriers. Employers will be able to depend on them, and valuable occupations will have more prospective members.

Providing a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers is a simple tweak that recognizes that our immigration policy doesn’t account for people in their situation. Telling people to get in line misses the mark because there is no line for those currently protected by DACA.

From farmworker to table

Like Dreamers, farmworkers tend to be a sympathetic case. The dependence of the U.S. agricultural sector on undocumented immigrants is one of the mind-boggling facts about the American immigration system. In national surveys of agricultural workers, barely half are legal workers.

Of the documented and undocumented workers, 78 percent have been in the U.S. for more than ten years. In the most recent survey from 2016, only three percent of workers had been in the U.S. for less than a year.

Much like the Dreamers, these are people who have woven themselves into the fabric of American society. It’s likely that an immigrant picked the food at your grocery store. It turns out public policy is the reason for this. Current policies make it difficult to come legally through existing pathways.

Current agricultural visa programs are complicated and expensive

It’s difficult but not impossible for agricultural companies to find legal workers through existing visa programs. Across the entire industry, H-2A workers make up 10 percent of farm labor. H-2A visas are seasonal work permits for agricultural laborers. H-2A worker requests tripled from 2010 to 2020. In the first quarter of 2021, only four percent of requests were denied.

Some might see this 96 percent approval rate as strange given COVID-19’s effect on employment rates — shouldn’t we restrict these visa programs to reserve agricultural jobs for Americans? But that misunderstands how to send the American economy into a strong recovery. Even during economic downturns we should keep these visa programs open. Robust recoveries depend on getting Americans back into their much more lucrative positions, not giving accountants jobs picking crops. In the short-term, H-2A workers get crops from the farm and onto our tables.

So if the H-2A visa program approves so many foreign workers, why are there so many undocumented workers picking crops? Why does the 2016 NAWS data indicate a nearly half-and-half split on work authorization for agricultural workers? For one, NAWS does not include H-2A workers. So it underestimates the legal workforce by however many H-2A visas are issued in a given year. But the biggest explanation is cost.

Using the H-2A program turns out to be expensive. It requires that employees be paid at a minimum wage set by the Department of Labor that is higher than the minimum wage set for native workers, making it expensive to employ H-2A workers. This policy is meant to protect the positions for natives. In addition to the high wage required to use the H-2A program, companies must also provide housing and transportation for H-2A workers.

One of the most promising and simple tweaks to the H-2A visa program in the Farm Workforce Modernization Act is softening the seasonal requirement tied to H-2A visas. On top of the wages, housing, and transportation requirements, employers have to demonstrate that they face seasonal work demands.

That seasonal work requirement doesn’t seem like a big deal until you consider industries that have year-round labor needs. Dairies, for example, don’t experience seasonal changes in demand. Because the dairy industry doesn’t experience seasonal fluctuations, they are unable to meet their labor needs through the H-2A program. Farm and dairy associations, like the New York Farm Bureau, have lobbied for years to open the H-2A program to create a legal workforce without seasonal constraints.

The proposed modernization legislation offers 20,000 H-2A visas to year-round employers. That should go a long way towards meeting the need for agricultural workers in year-round industries. For example, there are about 150,000 dairy workers in the U.S., which means that this visa expansion is a sizable increase in the number of workers that dairies can hire. Providing avenues for filling open jobs at U.S. industries strengthens the economy, and will benefit the entire country in other ways as well.

Reforming the H-2A program can reduce illegal immigration

H-2A reform also reduces illegal immigration. By making the process easier for employers to work within, and by introducing options for peaceful workers already here to legalize their status, there will be less incentive for workers to enter illegally and less need for employers to turn to undocumented workers. And because the bill would introduce additional enforcement, that may encourage businesses to hire legal workers instead.

Much of the reliance on undocumented labor stems from the relationship between Mexico and the southern U.S. The history of the southern border isn’t as clean as the lines shown on maps imply. For years, communities along the border had much more informal back-and-forth movement of people. Migration for seasonal farm work was circular because that was what both employers and the workers wanted. Immigrants came for harvests and then returned to Mexico or other nearby countries. The Bracero Program is one example, where Mexican guest workers came to the U.S. for temporary work. Yet even that was a formalization of earlier practices where workers came and went each season.

Today’s borders better reflect what is seen on the map. Increases in border enforcement meant that coming to the U.S. was more difficult. In turn, more difficult crossings made people less likely to return to their home country for fear that they wouldn’t make it back. So what had been a circular flow became a one-way movement. This is an unintentional outcome, but one that expanding the H-2A program can mitigate. Rising H-2A admissions broadly track the reduction in apprehensions per Border Patrol agent since 1987. In short, the Farm Workforce Modernization Act’s expansion of H-2A visas should reduce illegal immigration by giving workers and employers a legal option.

Of course, that reduction doesn’t deal with the undocumented workers in the U.S. already. The most practical response there should be removing dangerous individuals and requiring a strict standard for restitution for peaceful workers with immigration law violations. That requires creating a pathway for undocumented workers to regularize their status.

The Farm Workforce Modernization Act gets at this by instituting a fine of $1,000 for working illegally and requiring a background check. In addition, a worker who has been in the U.S. for 10 years can get in a new line created by the legislation to earn a green card. That requires not just a fine, but an additional four years of work. Eight years of additional work are required for those who have been in the U.S. for fewer than 10 years before they can apply for a green card.

To respond to fears that pathways to permanent residency might encourage illegal entry, the Act also requires E-Verify be used by employers. E-Verify is a federal program run by the Department of Homeland Security allowing businesses to verify if an employee is eligible to work in the U.S. Several states already require E-Verify, and government contracts generally require it as well. But the Farm Workforce Modernization Act would make it mandatory for all agricultural employment in the hopes of discouraging future undocumented workers from coming to the U.S..

These big steps also come with a lot of simple modernizations, for example, allowing electronic job postings for H-2A positions and consolidating applications to streamline the process for employers. Those are overdue and uncontroversial changes that bring the system into the 21st century. Together, the reforms will make the U.S. agricultural industry stronger and reduce illegal immigration.

Only legislation can improve the immigration system

The Dream Act and Farm Workforce Modernization Act both represent Congress stepping up to the plate on immigration reform. A concerning move in immigration policy has been the increase in executive actions because of Congress’s failure to secure legislative reform. President Trump’s administration demonstrated just how much sway the presidency holds over immigration issues. But before his administration, President Obama’s administration created DACA. This movement from defining immigration policy through the executive branch should be reversed with smart legislative updates to immigration policy.

Legislative action can reap the benefits of modernizing the immigration system. By creating a line for farmworkers and Dreamers, Congress can ensure that our agricultural sector and the communities that immigrants live in both thrive. The root of our economy’s dependence on illegal immigration has always been that legal entry is too difficult.

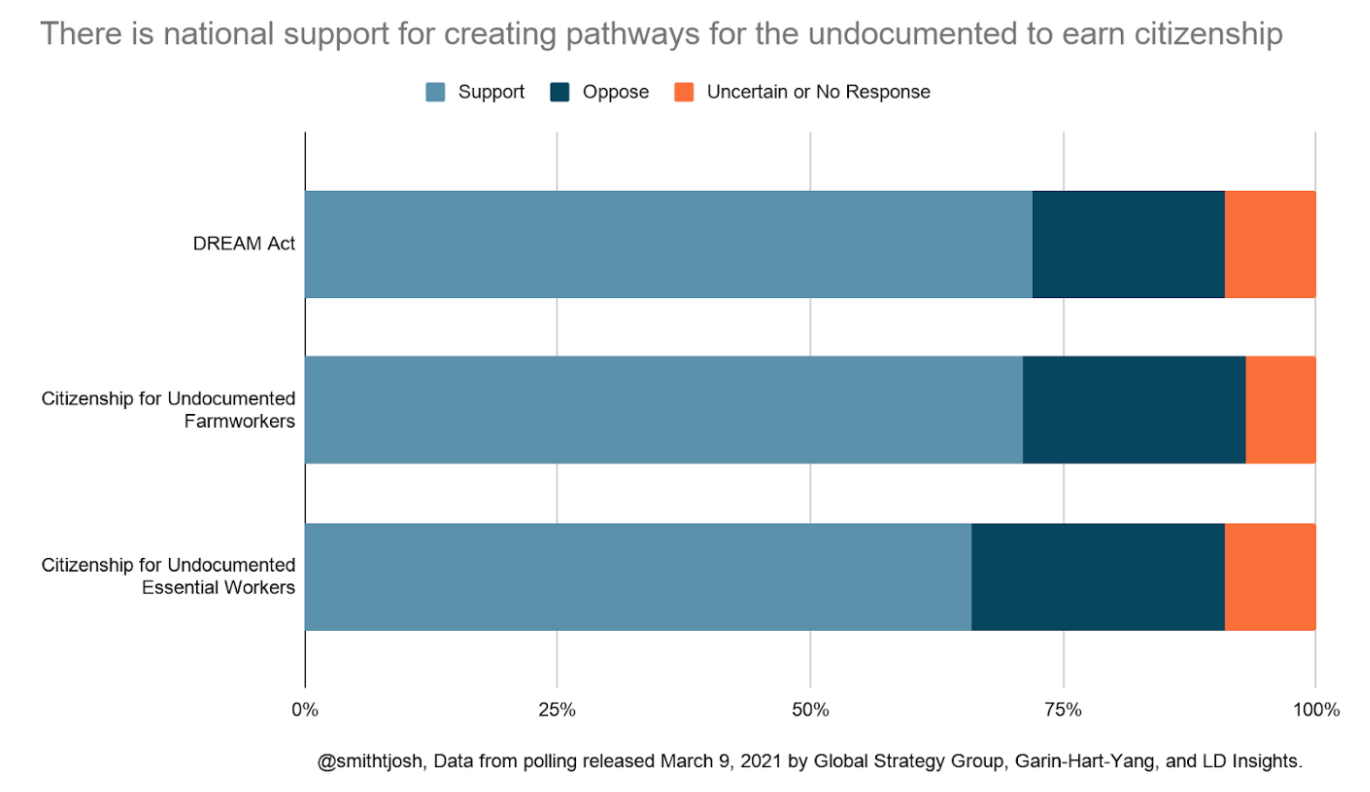

Members of Congress shouldn’t fear negative reactions from voters either. A late February poll by Morning Consult and Politico showed that about 60 percent of voters approve of a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Only 24 percent disapproved. And a survey released on March 9 suggested that there is bipartisan support. Most Republican voters, for example, preferred citizenship to deportation, 61 percent to 39 percent. Across the country, most voters supported a path to citizenship for Dreamers, essential workers, and farmworkers.

Source: Global Strategy Group, Garin-Hart-Yang, and LD Insights, March 9, 2021.

Reform that clarifies immigration processes will meet the needs of U.S. businesses and reduce illegal immigration. That’s the promise of updates like the Dream Act and the Farm Workforce Modernization Act: a U.S. immigration system that emphasizes legal pathways to the American dream.