Occupational licensing laws establish mandatory minimum entry requirements that must be met for aspiring professionals to begin working. These requirements include completing minimum levels of education and training, paying various fees, passing examinations, and satisfying “good moral character” standards. In the early 1950s, approximately 5 percent of workers in the United States were required to obtain a license to work.1Morris Kleiner, “Occupational Licensing,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14, no. 4 (2000): 189–202. As of 2019, the percentage of workers has grown to almost 22 percent.2Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Data on Certifications and Licenses,” last modified January 22, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/cps/certifications-and-licenses.htm.

This is nearly 10 times the fraction of workers (2.3%) receiving the federal minimum wage3Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers, 2017,” BLS Reports, Report 1072, March 2018, https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2017/home.htm. and more than double the percentage of workers (10.3%) that are union members.4Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union Members Summary,” news release, January 22, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm. Occupational licensing primarily occurs at the state level, but there are some examples of federal licensing, as well as variation at the county and municipal levels.

Some occupations, such as those of physicians, dentists, and registered nurses, are licensed in every state with little variation in licensing requirements. Other occupations, such as barbering and cosmetology, are universally licensed but with significant state-to-state variation. Barbers, for example, must complete 2,100 hours of education in Iowa— more than double the number of hours mandated in New Hampshire (800).5Dick M. Carpenter III, Lisa Knepper, Kyle Sweetland, and Jennifer McDonald, “The Continuing Burden of Occupational Licensing in the United States,” Economic Affairs 38, no. 3 (2018): 380-405. ; Edward Timmons and Robert Thornton, “The Licensing of Barbers in the USA,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48, no. 4 (2010): 740–57. Some occupations (such as those of massage therapists and radiologic technicians) are licensed in most states; others (e.g., lactation consulting and interior design) are licensed in only a few states. There are even examples of occupations that are licensed in only one state—such as florists in Louisiana.

To better understand the costs associated with occupational licensing requirements, we will use barbers as an illustrative example. As of September 2020, barbers require a license in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.6The Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation. Barber Licensing Data. https://csorsfu.com/. Using data provided through the Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation at Saint Francis University, we find that there is a large discrepancy in the fees required to obtain a barber’s license across states—from $10 in Pennsylvania to $450 in Alaska. Fees are far from the only requirement prospective barbers must meet to obtain a license. Other costs take the form of time spent on experience and training, different forms of examination, and good moral character requirements.

In the case of barbers, degree requirements range from none at all in some states to proof of graduation from a licensed barbering college in others. These educational programs can vary drastically in cost. In the 2019-2020 academic year, the average cost of tuition, books, and sup- plies was more than $15,000 per year.7Barbering/Barber Career Program Tuition & Fees Comparison, College Tuition Compare, https://www.collegetuitioncompare.com/compare/tables/vocation-al-program/barbering-barber/. This is a comparatively high cost considering that the 2019 median pay for barbers and other hairstylists was approximately $26,270 a year, or just under $13 per hour.8Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Barbers, Hairstylists, and Cosmetologists,” Occupational Outlook Handbook, last modified September 1, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/ooh/personal-care-and-service/barbers-hairstylists-and-cosmetologists.htm.In most states, after completing the education or experience requirements (thousands of hours of hands-on experience in some cases), prospective barbers must complete examinations. States vary in their examination requirements, but exams may be written, practical, or theoretical—or a combination of all three. After paying for education expenses and examinations, prospective barbers are also required in most states to demonstrate good moral character by disclosing any criminal history. In many cases, good moral character requirements might bar individuals with non-dangerous records from employment.

Barbers have mixed feelings about the licensing requirements and prospects for future reform. For example, in Arkansas, where there was a senate bill to abolish the State Board of Barber Examiners, barbers pro- tested and noted that the proposal “definitely takes the professionalism, and it definitely takes the craft out of what we do and it just puts us in layman’s terms.”9Quoted in Casey Frizzell, “Barbers Upset with Cuts Proposed Bill Would Make in Arkansas,” 5 News, March 7, 2019. Others also struggle with the prospect of what’s known as a transitional gains trap.10Gordon Tullock, “The Transitional Gains Trap,” Bell Journal of Economics 6, no. 2 (1975): 671–78. If licensing laws are repealed, then the time and money thousands have spent to obtain a license may become obsolete and, in the words of one director of an Arkansas barber college, the repeal “makes the license that they receive pointless.”11Quoted in Zack Briggs, “Bill Would Abolish Arkansas Barber Board, No License or Education Required to Cut Hair,” KATV, March 6, 2019.

While these feelings do persist, there is also the long-term situation to consider. When a similar Texas bill that would abolish the requirement that barbers be licensed, Texas state representative Matt Shaheen explains that “the legislation was created to expand employment opportunities. Texans that are willing to join the workforce and compete—especially low-income Texans looking to improve their lives—should face the fewest obstacles possible.”12Quoted in Camille Connor, “Barbers, Cosmetologists against Texas Bill That Would Do Away with Licenses,” News Channel 6, March 13, 2019. Both the Arkansas and Texas bills did not become law.

Why are occupations licensed and why are there such vast differences from state to state? Economists have developed two theories.13For a study that utilizes a similar approach of defining the relevant theories on the effects of licensing, see A. Frank Adams, John Jackson, and Robert Ekelund, “Occupational Licensing in a ‘Competitive’ Labor Market: The Case of Cosmetology,” Journal of Labor Research 23, no. 2 (2002): 261–78. The first theory focuses on the supply side of the labor market. By making it more difficult for aspiring workers to enter the licensed profession, licensing ensures that fewer individuals have the ability to enter the occupation. This reduction in supply results in the licensed practitioners having the ability to earn higher wages and charge higher prices for their services. Therefore, this theory suggests that welfare declines as a result of occupational licensing. Occupational licensing comes about and is able to persist as a result of concentrated benefits being received by the licensed professionals and individuals that develop a financial stake in the persistence of the regulation (e.g., schools and examining bodies). The costs associated with licensing, on the other hand, are dispersed among a larger number of people, and thus individuals are less passionate about limiting new or eliminating existing occupational licensing legislation. Nobel prize winning economist Milton Friedman advanced this theory specifically in the case of occupational licensing, and the theory was more formally outlined and generalized by economist Mancur Olson.14Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962); Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965). Practitioners will actively attempt to implement licensing as a means of increasing their own benefit.15George J. Stigler, “The Theory of Economic Regulation,” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 2, no. 1 (1971): 3–21. Practitioners’ differing abilities to organize into interest groups and influence state legislators will result in significant differences in licensing legislation from state to state.

An alternative theory of occupational licensing instead focuses on the demand side of the labor market. Consumers have less information about the qualifications, reputation, and ability of a professional than the professional has about him- or herself. By establishing minimum quality standards, occupational licensing alleviates this gap in information (known as the asymmetric information problem). As a result, occupational licensing may potentially increase welfare. This theory was originally developed by Nobel prize winning economist George Akerlof and later applied specifically to occupational licensing by economist Hayne Leland.16George Akerlof, “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84, no. 3 (1970): 488–500; Hayne Leland, “Quacks, Lemons, and Licensing: A Theory of Minimum Quality Standards,” Journal of Political Economy 87, no. 6 (1979): 1328–46. Berkeley economist Carl Shapiro also noted that occupational licensing may increase the human capital of licensed professionals by raising training levels, which may help to increase the quality of services that consumers receive.17Carl Shapiro, “Investment, Moral Hazard, and Occupational Licensing,” Review of Economic Studies 53, no. 5 (1986): 843–62.

Shapiro’s analysis showed that licensing may enhance welfare if professional qualifications and training are not observable, but will reduce welfare if training is observable. Professionals may use excessive investment into human capital as a signaling device—one that tends to benefit consumers who value high quality, but at the expense of consumers who do not value high quality. In addition, certification may potentially be inferior with respect to welfare than both licensing and market competition if professionals overinvest in training to serve as a signaling device.

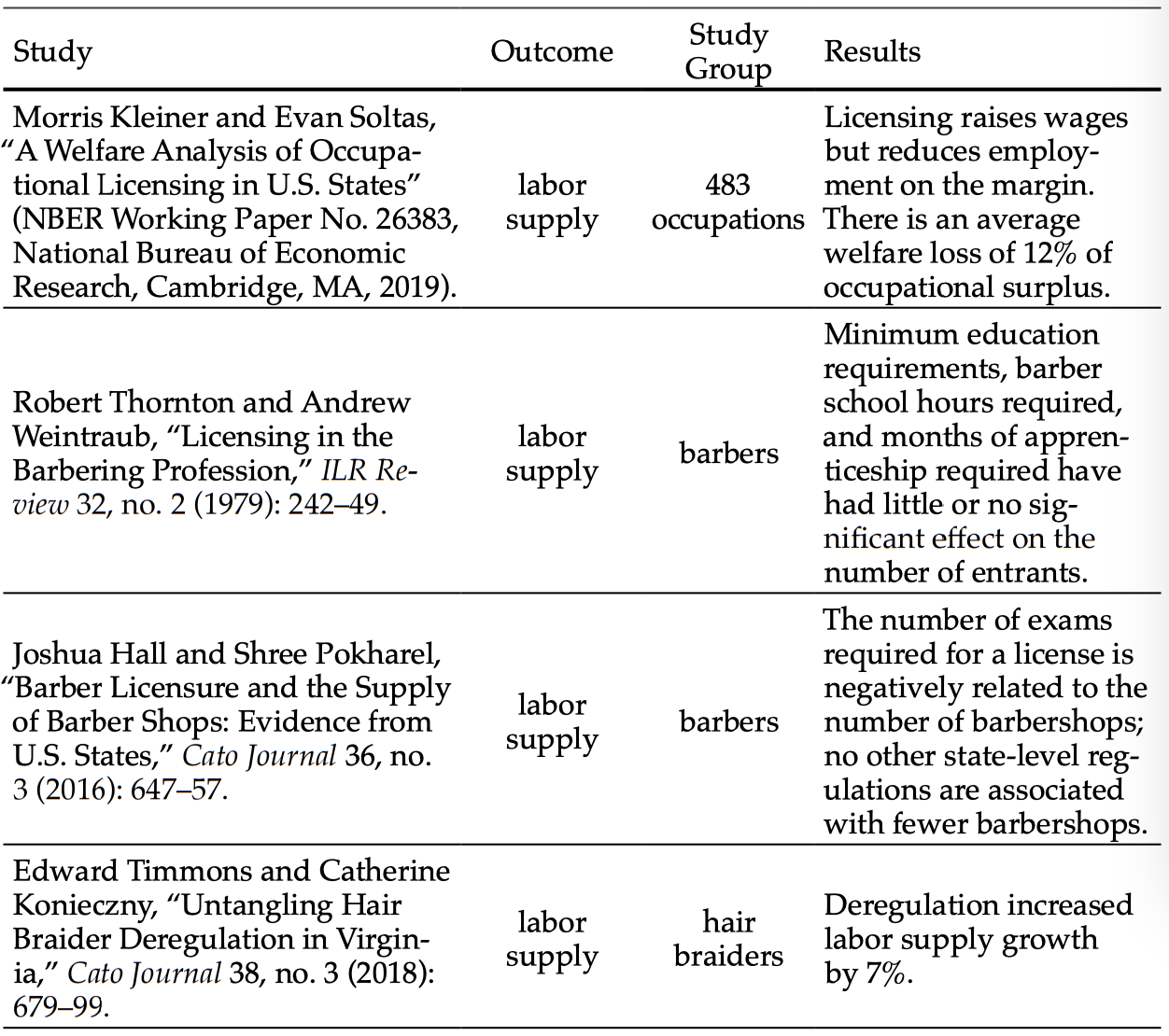

Other scholars have further expanded on this public choice theory of licensure by estimating market equilibriums in which licensure restricted the workers’ ability to supply their labor but also affected the demand for workers on the basis of quality and selection criteria. They find that licensing raised wages and hours but reduced employment and reduced average welfare.18Morris Kleiner and Evan Soltas, “A Welfare Analysis of Occupational Licensing in U.S. States” (NBER Working Paper No. 26383, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2019). Still other researchers studying the relationship between occupational licensing and public choice argue that practitioners favor licensing to reduce competition and keep inflated wages (which accords with the theory of public choice), but that public choice theory has limitations in capturing all of the potential harms of licensure.19Ryan Nunn and Gabriel Scheffler, “Occupational Licensing and the Limits of Public Choice Theory,” Administrative Law Review Accord 4, no. 2 (2019): 25–41. The researchers also suggest that public choice theory fails to theoretically address potential threats to public health and safety and places a disproportionate emphasis on studying professions in which the justification for licensure is the weakest.

Some scholars have argued that advances in technology have significantly reduced the effects of asymmetric information.20Adam Thierer et al., “How the Internet, the Sharing Economy, and Reputational Feedback Mechanisms Solve the ‘Lemons Problem’” (Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, May 2015). Consumers can use websites such as Yelp, Angie’s List, Google, and Facebook to gather information about the reputation and ability of professionals before completing a transaction. Research suggests that consumers may value and use consumer ratings in place of licensing status.21Chiara Farronato et al., “Consumer Protection in an Online World: An Analysis of Occupational Licensing” (NBER Working Paper No. 26601, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2020). It is also not clear why requirements for occupational licensing would substantially vary from state to state if regulators were primarily motivated by improving welfare. Further, there is little documented evidence of consumers being the primary lobbyists for new occupational licensing—instead, professional associations (and individuals with financial ties to the regulation) are generally the fiercest defenders and supporters of occupational licensing.22Morris Kleiner, Licensing Occupations: Ensuring Quality or Restricting Competition? (Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2006).

The fact that many licensed professionals fear that licenses will be “worthless” if barriers to entry are removed (the transitional gains trap) also seems to be more consistent with the supply-side theory than the demand-side theory. If licensing were primarily operating as a signaling device, the license should still serve an important purpose of signaling quality despite competition from unlicensed professionals.

Certification represents one regulatory alternative to occupational licensing. The state of California, for example, issues certificates to mas- sage therapists. Individuals without a certificate are free to practice massage therapy, but may not use the protected title “certified massage therapist.” Unfortunately, public perception often equates “regulation” with “licensing.” In reality, occupational licensing represents the strictest form of occupational regulation—an outright ban on practice unless individuals meet entry requirements. In Capitalism and Freedom, Milton Friedman defines less stringent forms of regulation that he refers to as certification and registration. Certification protects a title but does not prohibit practice. Registration refers to the state collecting contact information from applicants and maintaining a list of practitioners. Each of these less-stringent types of occupational regulation is much less prevalent than licensing. Only 2.3 percent of workers are certified, and registration is likely even less prevalent.23Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.” Adding to public confusion, states often use all three terms interchangeably in statutes and administrative code—most often states use the terms certification and registration in place of licensing.24Robert Thornton and Edward Timmons, “The De-licensing of Occupations in the United States,” Monthly Labor Review, May 2015.

The Institute for Justice has identified additional alternatives to occupational licensing besides certification and registration.25John K. Ross, “The Inverted Pyramid: 10 Less Restrictive Alternatives to Occupational Licensing” (report, Institute for Justice, November 2017). Figure 1 shows the “inverted pyramid” depicting alternative forms of regulation—beginning with the least-restrictive option at the top (market competition) and the most-restrictive option at the bottom (occupational licensing). The shape of the inverted pyramid represents the restrictiveness of a form of occupational regulation—a larger area within the pyramid corresponds with more freedom for the market to function without restriction.

Market competition is at the top of the pyramid and represents the least intrusive means of regulating the market. At the other extreme, licensure represents the most restrictive government-intervention approach to regulating an industry, in that it does not allow an individual to provide a good or service without the express consent and permission of a government organization. The menu of options shown in figure 1 provides regulators with nine less-costly and less-intrusive means of addressing possible market failures. As noted previously, advances in technology have likely reduced the potential for market failure, and the case that can be made for occupational licensing has weakened over time.

In the sections that follow, we trace the history of licensing and the origins of occupational licensing, before turning to a summary of the existing empirical literature on its effects. We then provide some important visualizations of the scope and effects of licensing before offering a framework for reform.

History of Occupational Licensing

Occupational licensing has a rich and expansive history. Rules governing occupations can be traced back to the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, circa 1700 BC. These early rules outlined expectations

Figure 1. Alternatives to Occupational Licensing

Source: John K. Ross, “The Inverted Pyramid: 10 Less Restrictive Alternatives to Occupational Licensing” (report, Institute for Justice, November 2017).

about prices for medical services and punishments for negligent practitioners. There is evidence that occupational regulation also existed quite early in China: competency examinations were used as a determinant of job proficiency in small, wealthy circles as early as the Han dynasty, and were expanded in the late seventh century AD by Wu Zetian of the Tang dynasty. These occupational regulations were known as the Imperial Examination. Members of any socioeconomic class in the country could pay an application fee and take a civil service examination; those who passed met the requirements to become a candidate for the state bureaucracy.26Benjamin Elman, Civil Examinations and Meritocracy in Late Imperial China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013). Later, during the Song dynasty, the program was regularized into a three-tiered system that included local, provincial, and court exams. Over the following few hundred years, the Chinese government expanded rudimentary licensing systems for dentists, physicians, and acupuncturists.27Yüan-ling Chao, Late Imperial China: A Study of Physicians in Suzhou, 1600–1850 (New York: Peter Lang, 2009).

Eventually, the idea of restricting entry into occupations to maintain a standard of performance, ensure quality and safety, and limit competition began to appear in Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries with the popularization and expansion of medieval guilds.28Occupational Licensing Legislation in the States (Chicago: Council of State Governments, 1952). Guilds were found within Germany, Naples, Sicily, and Spain. These were often made up of artisans or merchants who oversaw the entry into and practice of their craft or trade within a particular geographic region. These guilds often enforced their authority as a rudimentary professional association through grants of letter patents from monarchs. Gaining entry into these exclusive organizations often involved paying fees and dues and meeting competency requirements.

The foundations of occupational regulation in the United States were laid in the early colonies. Some later developments can be traced to the ideas of Scottish author Adam Smith, commonly regarded the father of modern economics. Smith discussed early forms of occupational regulation in his most well-known work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, such as regulations that limited the number of apprentices a skilled craftsman could undertake and regulations that limited the length of apprenticeship programs.29Chapter X: On Wages and Profit in the different Employments of Labor and Stock. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. (1776). Many of these ideas were incorporated into US state-level regulation concerning apprentices and property rights for many categories of workers such as bakers, leather merchants, lawyers, and innkeepers. During the 19th century some states and localities chose to progress from industry regulation to early forms of licensure that granted the right to practice to approved individuals only; examples can be found applying to barbers, embalmers, farriers, pawnbrokers, and a selection of other professionals.30Paul Larkin Jr., “Public Choice Theory and Occupational Licensing,” Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 39, no. 1 (2016): 209–331. These examples of occupational licensing were rare and hotly debated until a Supreme Court ruling in 1889 upheld the constitutionality of state efforts to regulate the medical profession for the purpose of promoting and maintaining health and safety.31Dent v. West Virginia, 129 U.S. 114 (1889).

Within the United States, occupational licensing was sparse until early in the Progressive Era (1890–1920)32Before 1870, a minority of states had early occupational licensing for attorneys, dentists, insurance brokers, physicians, and teachers. Between 1870 and the beginning of the Progressive Era, in 1890, some states also added additional licensing requirements for pharmacists and veterinarians. Marc Law and Sukkoo Kim, “Specialization and Regulation: The Rise of Professionals and the Emergence of Occupational Licensing Regulation,” Journal of Economic History 65, no. 3 (2005): 723–56. and was often undertaken by national professional organizations—most notably the American Medical Association (AMA) for physicians, which was established in 1847. The publicly stated mission of the AMA was to advance scientific research, improve public health, and create a consistent set of standards for medical education. The AMA also serves as a form of trade union by restricting the number of people who can enter a medical occupation, and therefore indirectly affects wages and limits potential competition by restricting the practice of medicine to exclude other professionals such as chiropractors and barbers.33Friedman. Chapter IX: Occupational Licensing. Capitalism and Freedom. (1962). In 1908, the Council on Medical Education within the AMA contracted the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching to survey the American medical education system with regard to public health and safety. Abraham Flexner was chosen to survey the 155 medical schools that existed at the time within North America, and found substantial differences in curriculum, assessment, and requirements for graduation.34Thomas Duffy, “The Flexner Report—100 Years Later,” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 84, no. 3 (2011): 269–76.

In 1910, Flexner published his findings in a report, titled Medical Education in the United States and Canada, that outlined specific recommendations for creating a single model of medical education. Direct consequences of this report included the closure or consolidation of many inefficient or understaffed medical schools, a series of rules stating that a new medical school cannot be created without the permission of the state government, and a set standard of education for those intending to be considered medical practitioners. Flexner’s report laid the groundwork for modern licensing, in that it established that all physicians receive at least six years of postsecondary formal instruction in order to practice medicine—instruction that adheres closely to the scientific method and maintains the protocols of scientific research. The medical doctor field, though the most notable example, was not the only field that adopted a form of occupational regulation and licensure during the Progressive Era. Many states introduced licensing requirements for professionals including accountants, architects, chiropractors, engineers, nurses, optometrists, and plumbers.35Law and Kim, “Specialization and Regulation.” By the mid-20th century, there were nearly 1,200 state licensing statutes and approximately 5 percent of jobs in the United States required an occupational license.36Law and Kim, “Specialization and Regulation”; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.”

The Progressive Era marked the beginning of modern occupational licensing systems in the United States. Occupational licensing under- went rapid expansion between 1950 and the late 2010s. There are many views about why this expansion occurred, two of which are referenced in the previous section. In summary, technological advances and increased professional specialization had made it increasingly difficult for consumers to judge differences between service providers.

Proponents of occupational licensing have often argued that they decrease consumer uncertainty and increase demand for licensed services while also providing a wage premium to incentivize individuals to invest in education and experience.37Kenneth Arrow, Essays in the Theory of Risk-Bearing (United States: Markham, 1971); Morris Kleiner and Alan Krueger, “The Prevalence and Effects of Occupational Licensing,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48, no. 4 (2010): 1–12. Opponents have often argued in response that these laws create unnecessary barriers to entry, limit competition by reducing the equilibrium labor supply, drive firms to locate inefficiently, reduce economic mobility, and raise prices—all while having negligible effects on the quality of products.38Alicia Plemmons, “Occupational Licensing Effects on Firm Entry and Employment” (Working Paper no. 2019.008, Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, 2019); Peter Blair and Bobby Chung, “Job Market Signaling through Occupational Licensing” (NBER Working Paper No. 24791, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2018); Brian Meehan et al., “The Effects of Growth in Occupational Licensing on Intergenerational Mobility,” Economics Bulletin 39, no. 2 (2019): 1516–28.

The expansion of occupational licensing laws since the mid-20th century can be partially attributed to the structure of the economy. In 1950, when 5 percent of jobs required an occupational license, the US economy primarily consisted of manufacturing.39Occupational Licensing Legislation in the States. At the time, a large portion of manufacturing did not require specialized college-level education, and many employees were hired directly out of high school and gained training and experience on the job. These manufacturing jobs relied on unions to enact collective bargaining to maintain employee standards, employer-employee relations, and wages. In recent decades, there has been a shift as the US economy has become service-oriented. As service-oriented jobs have expanded in scope, so have the number of jobs with occupational licensing requirements.

During the expansionary period of occupational regulation, the percentage of jobs that require a license has grown substantially—nearly 22 percent of workers require an occupational license as of 2019.40Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.” In the early 20th century, most licensing requirements were set by state legislatures or by professional organizations. As service-based occupations have become more specialized and diverse, many states have elected to appoint a board of individuals familiar with the industry to review and set the requirements for entry. Almost all the time, individuals on these boards currently work within the industry and have an incentive to limit competition. In addition, the board members may work within institutions that train and educate applicants, giving them a financial incentive to increase education and training requirements. Also, many states do not have sunsetting procedures whereby potentially inefficient or outdated occupational licensing requirements can be reviewed to determine whether they are still necessary for the promotion of public health and safety.41Council on Licensure, Enforcement & Regulation, “Sunrise, Sunset and Agency Audits,” accessed February 22, 2020, https://www.clearhq.org/page-486181.

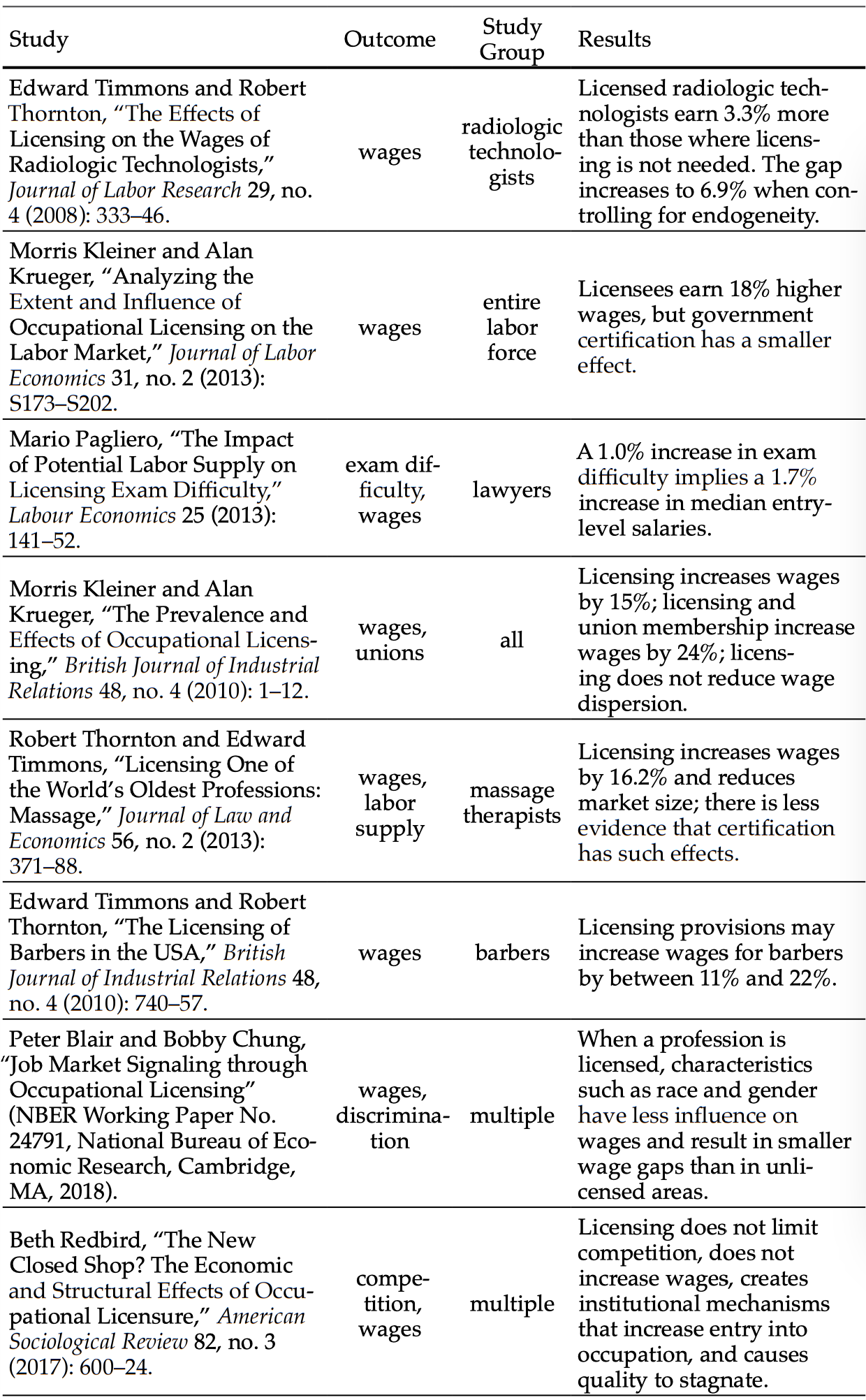

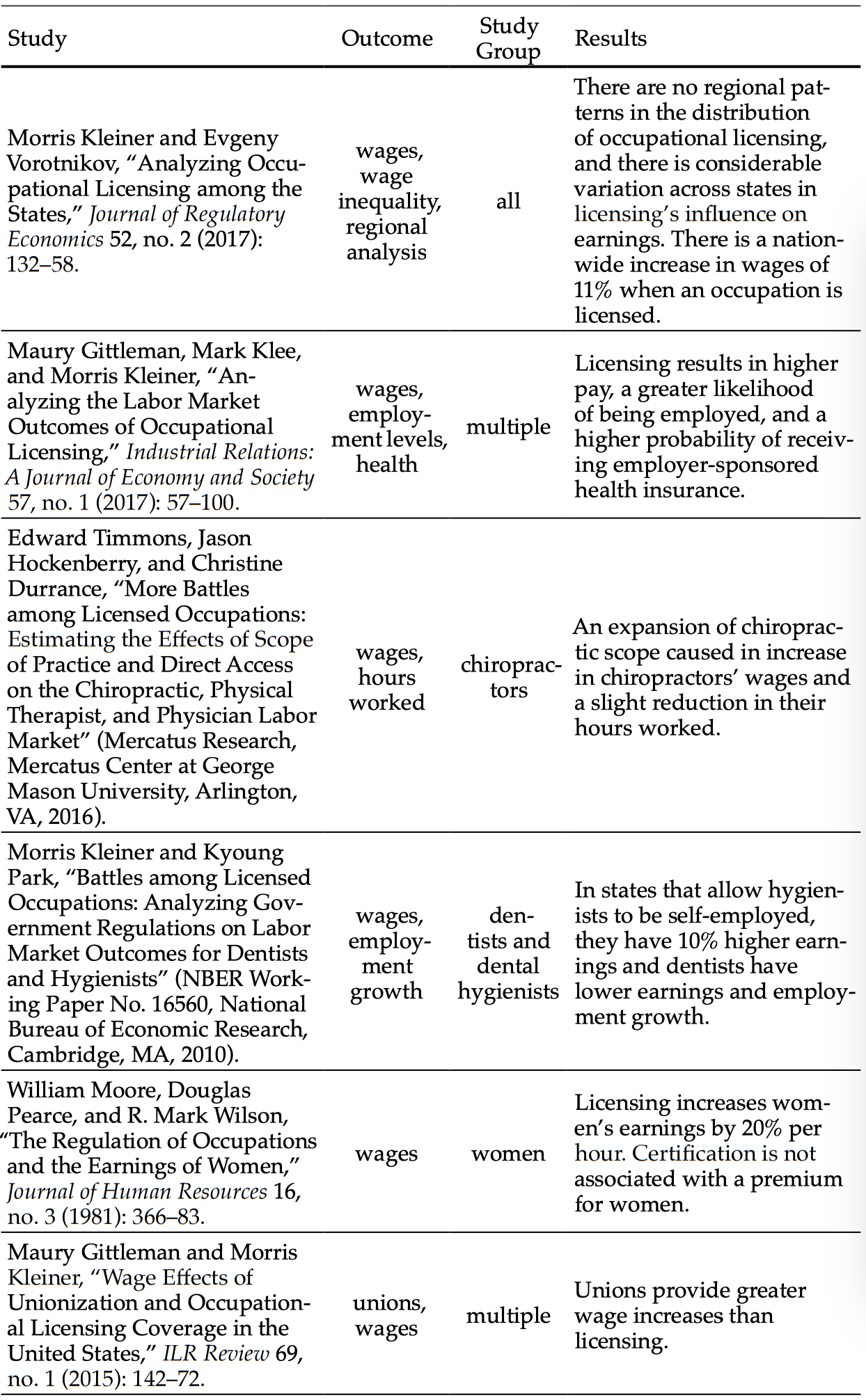

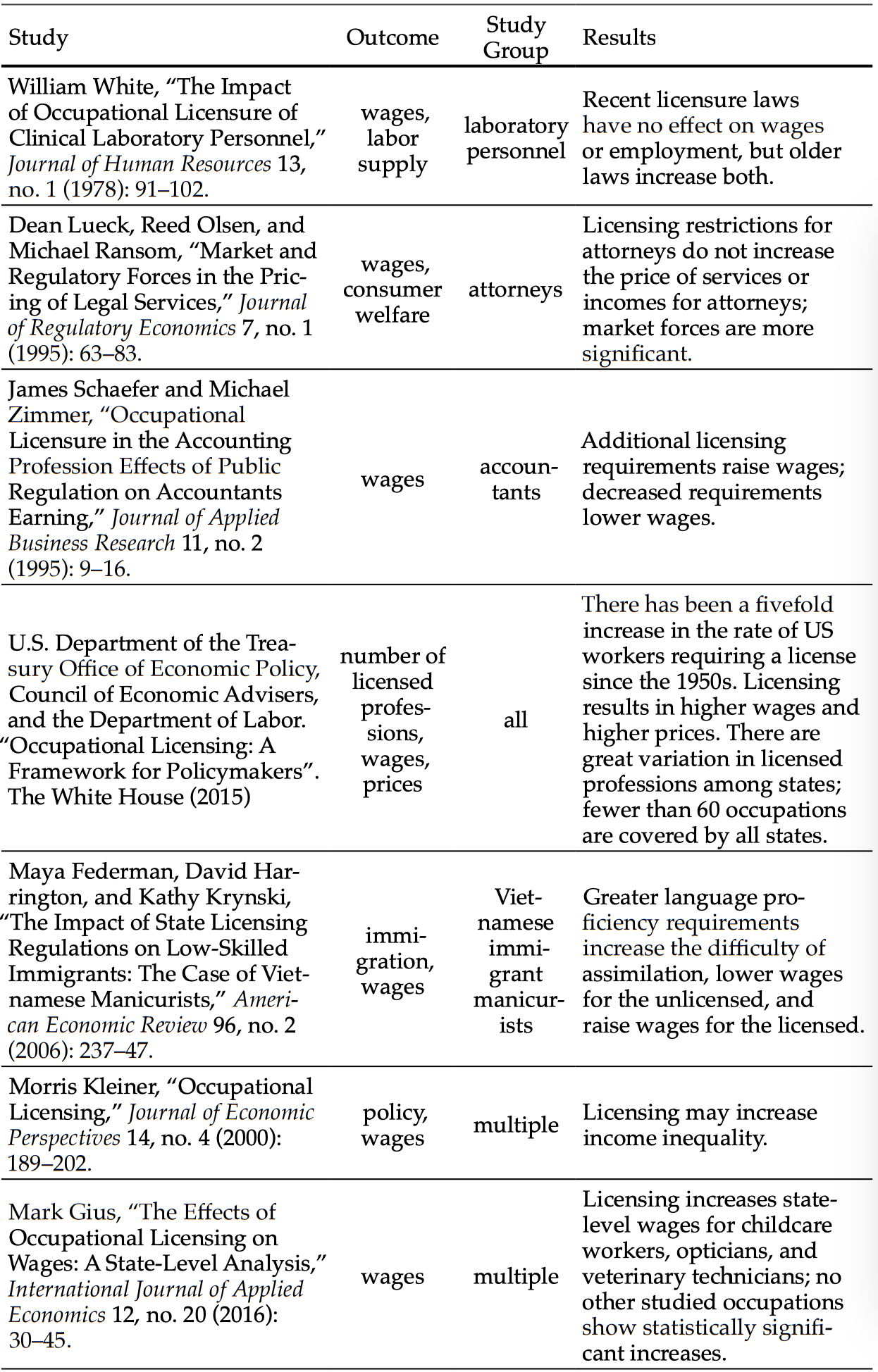

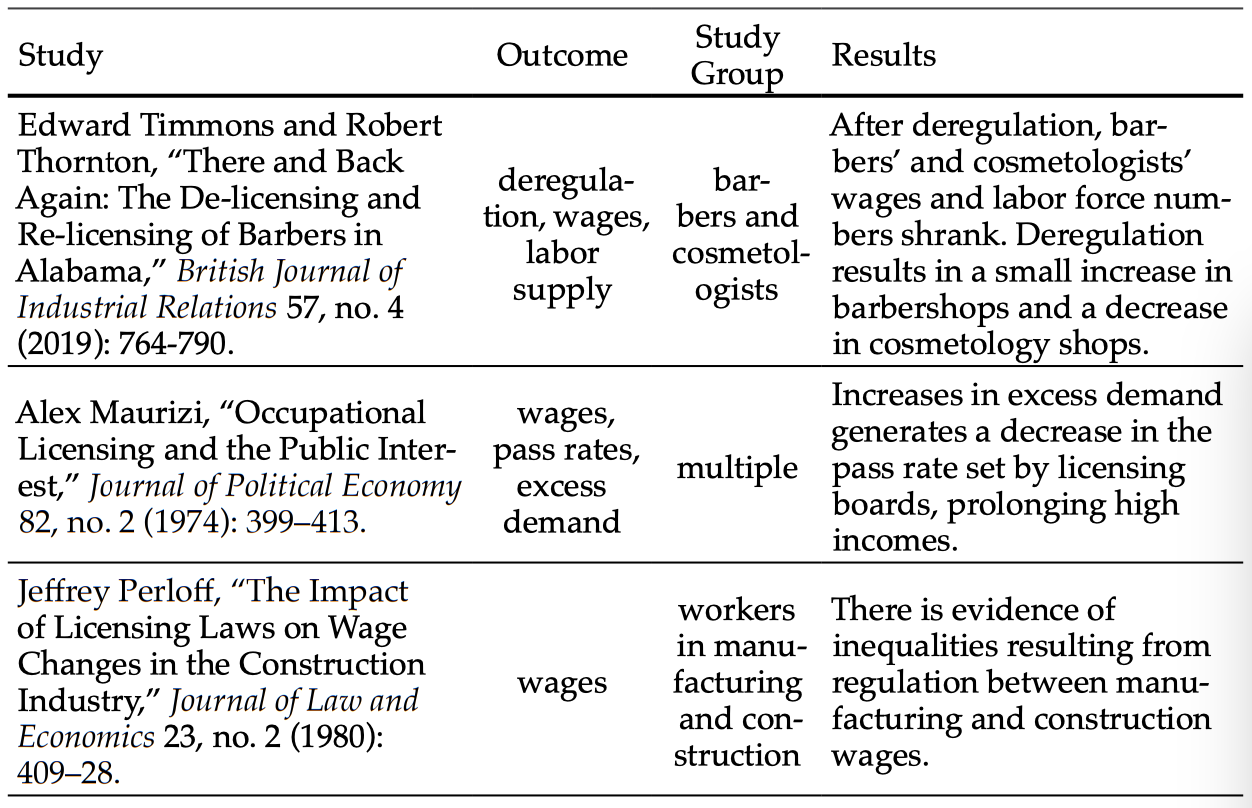

Literature

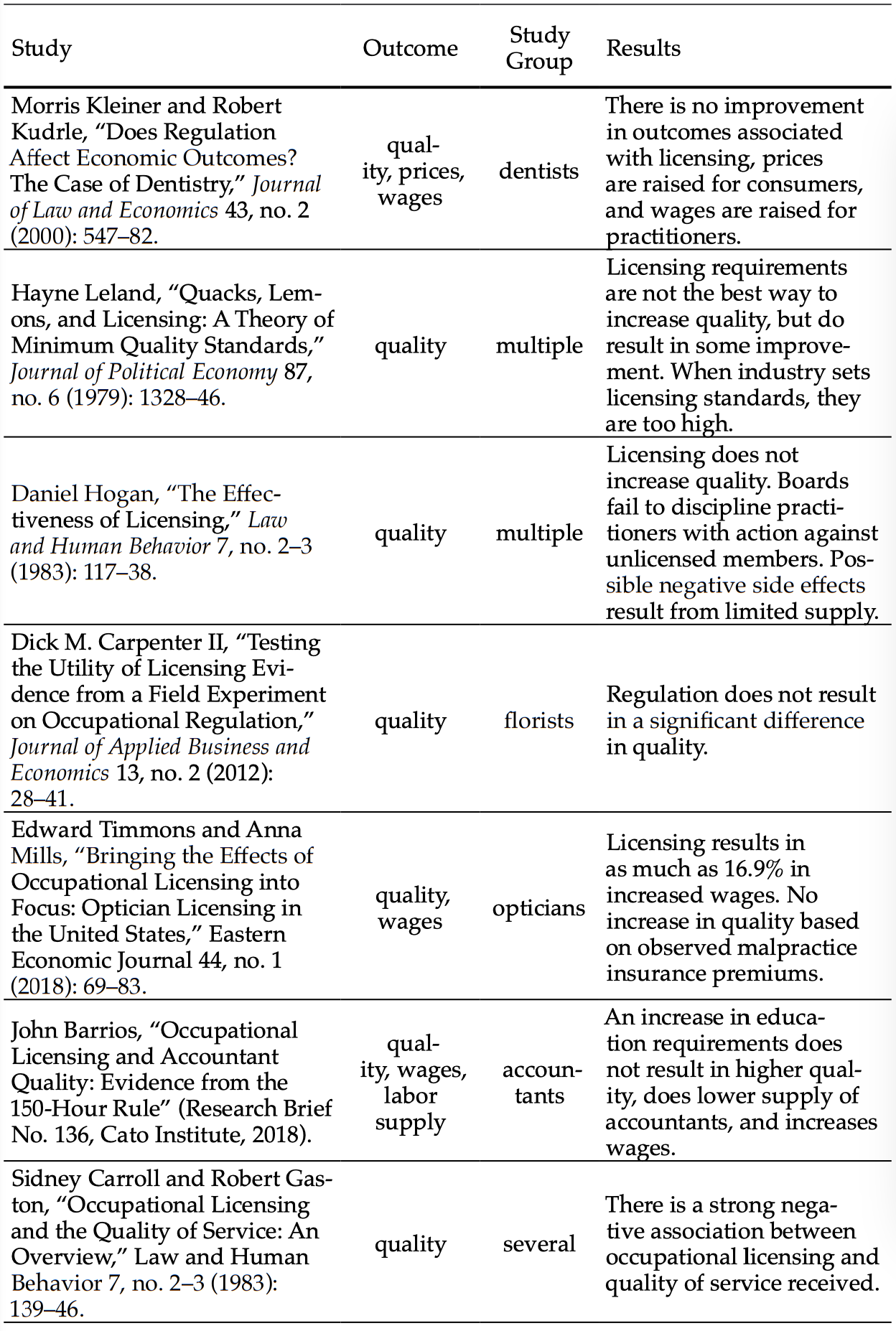

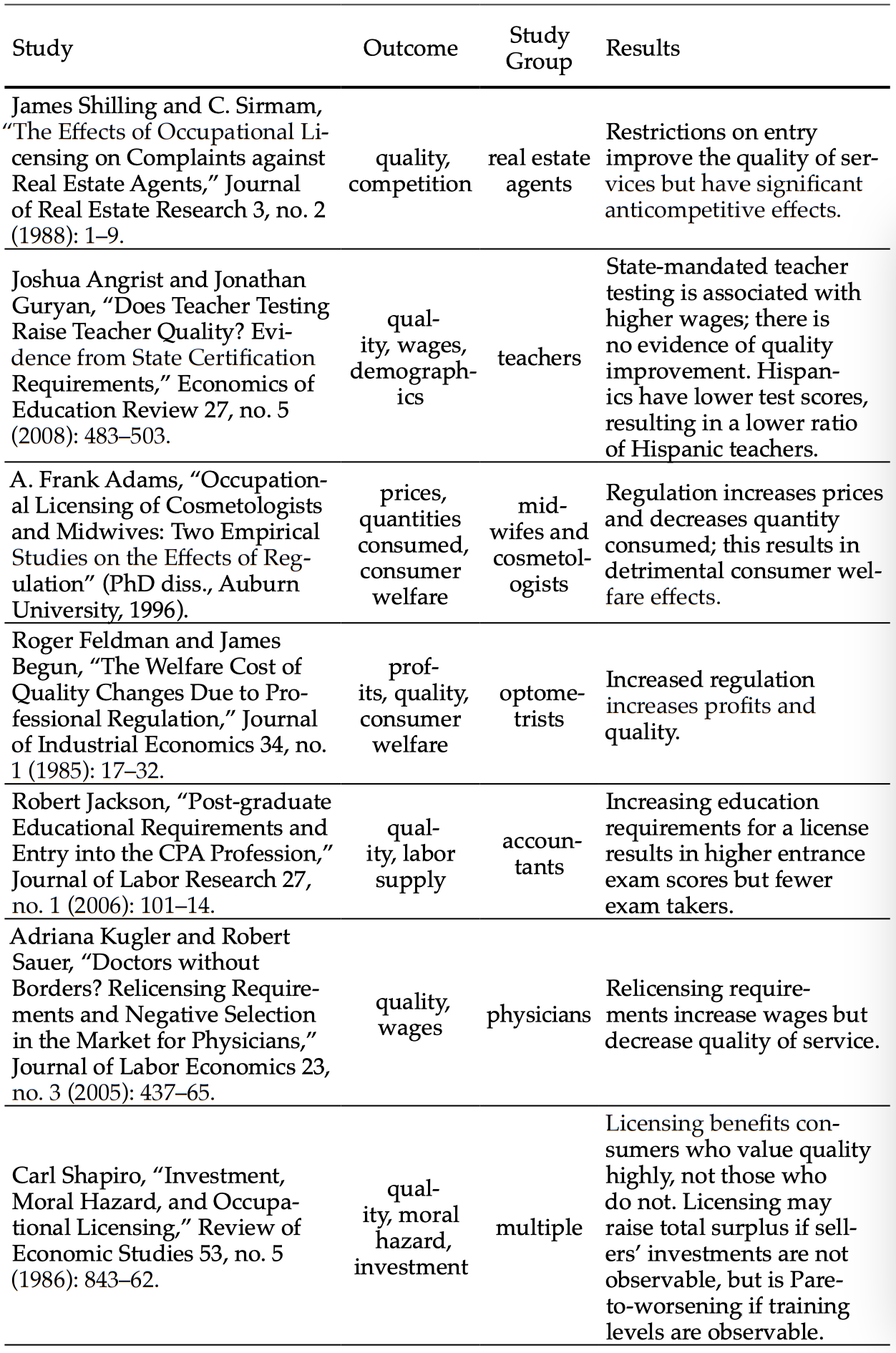

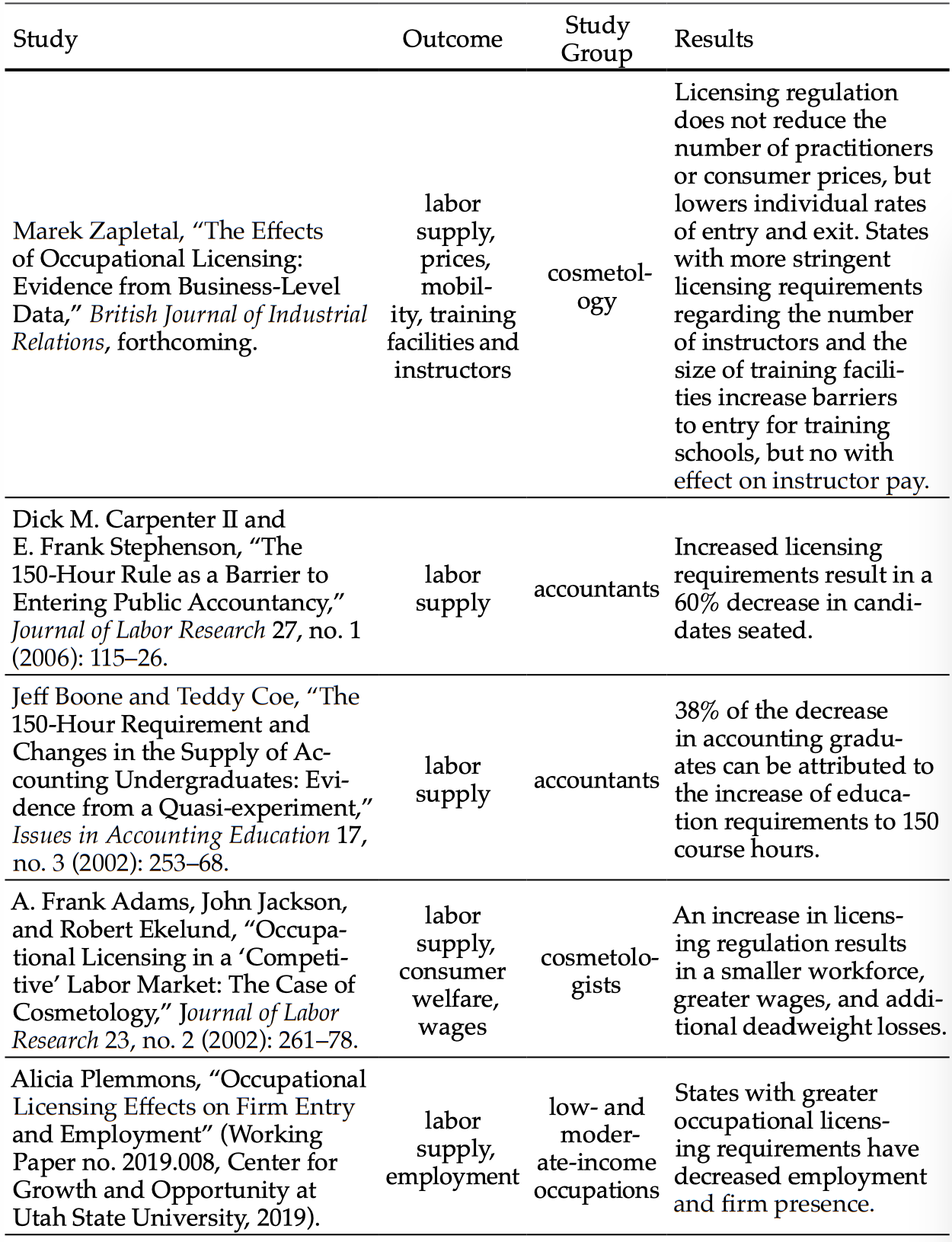

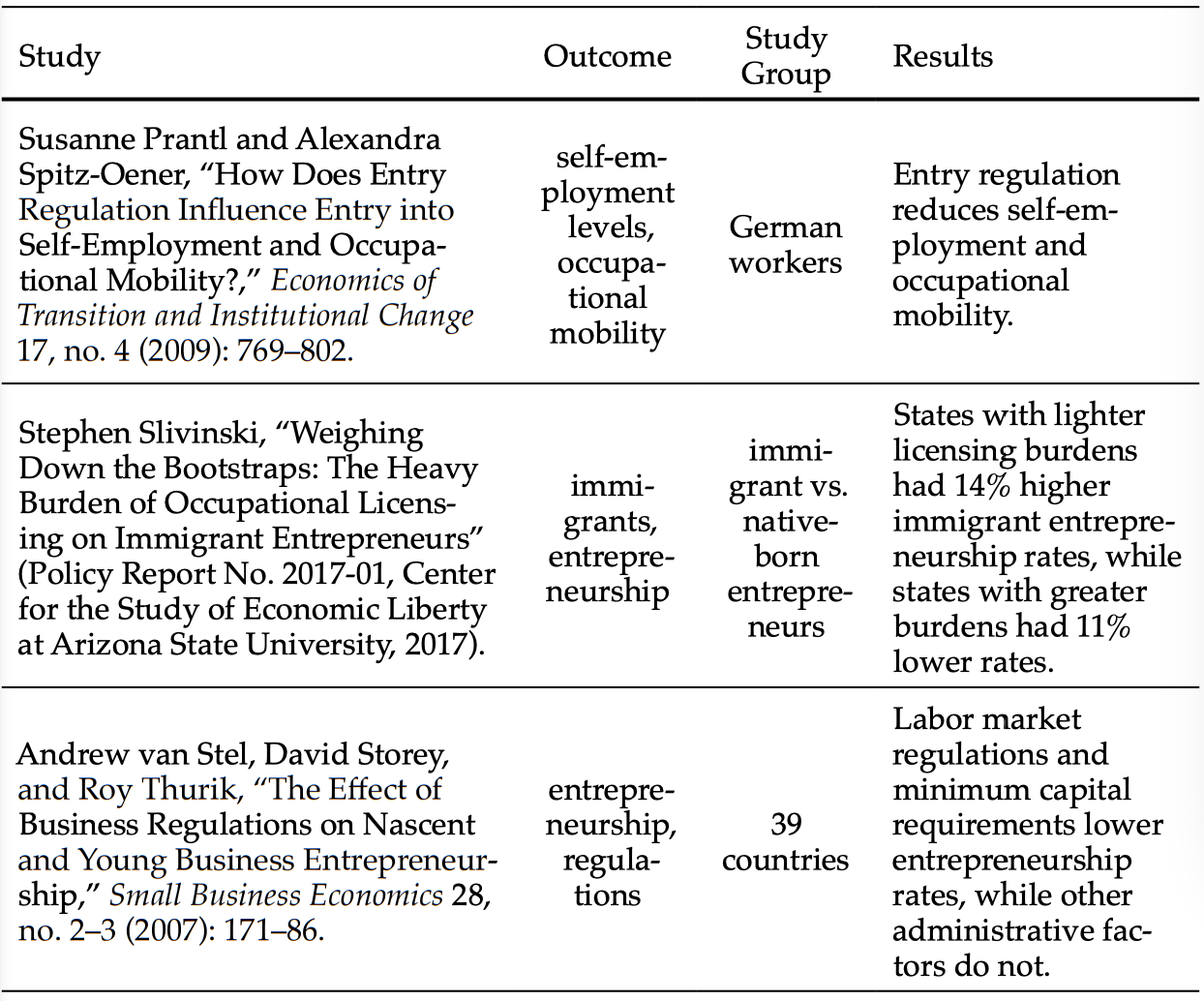

The appendix provides a list of studies divided by subject category. The first category focuses on how occupational licensing affects quality or the demand for goods and services. In general, these studies have been limited owing to data unavailability and the difficulty associated with measuring quality. The most common profession examined from the mid-1970s to shortly after the turn of the century was the dental industry. One study finds that the likelihood of adverse outcomes is reduced when licensing is present.42Arlene Holen, “The Economics of Dental Licensing” Arlington, VA: Public Research Institute of the Center for Naval Analysis, 1978. Two others, however, find little to no evidence of an effect on outcomes in dental hygiene.43Sidney Carroll and Robert Gaston, “Occupational Licensing and the Quality of Service: An Overview,” Law and Human Behavior 7, no. 2–3 (1983): 139–46; Morris Kleiner and Robert Kudrle, “Does Regulation Affect Economics Outcomes? The Case of Dentistry,” Journal of Law and Economics 43, no. 2 (2000): 547–82.

Quality studies have also been conducted in some other industries. A study that analyzed seven widely varying licensed occupations finds that licensing has either a negative impact or no impact on the quality of the services provided to consumers.44Carroll and Gaston, “Occupational Restrictions and the Quality of Service Received: Some Evidence” Southern Economics Journal, 47, no. 4, (1981): 959-976. Carl Shapiro provides a comprehensive theoretical model of the quality impacts stemming from occupational licensing and concludes that wealthier consumers who value high-quality goods and services greatly benefit from licensing, but lower-income individuals lose from tougher licensing standards through reductions in access.45Shapiro, “Investment, Moral Hazard, and Occupational Licensing.”

Occupational licensing is also likely to have an effect on the wages of professionals. One study finds evidence that licensure generally increases rents for massage therapists rather than affecting the quality of the service provided to consumers.46Edward Timmons and Robert Thornton, “Licensing One of the World’s Oldest Professions: Massage,” Journal of Law and Economics, 56, no. 2, (2013): 371-88. These rents are most commonly depicted through wage increases, for which estimates vary drastically across industries. Significant evidence of wage premiums has been documented for barbers, radiologic technologists, construction workers, dental hygienists, childcare professionals, opticians, and veterinary technicians.47Edward Timmons and Robert Thornton, “The Licensing of Barbers in the USA,” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 48, no. 4 (2010):740-57, December 2010; Edward Timmons and Robert Thornton, “The Effects of Licensing on the Wages of Radiologic Technologists,” Journal of Labor Research 29, no. 4 (2008): 333–46; Morris Kleiner and Kyoung Park, “Battles among Licensed Occupations: Analyzing Government Regulations on Labor Market Outcomes for Dentists and Hygienists” (NBER Working Paper No. 16560, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2010); Jeffrey Perloff, “The Impact of Licensing Laws on Wage Changes in the Construction Industry,” Journal of Law and Economics 23, no. 2 (1980): 409–28; Mark Gius, “The Effects of Occupational Licensing on Wages: A State-Level Analysis,” International Journal of Applied Economics 12, no. 20 (2016): 30–45; Edward Timmons and Anna Mills, “Bringing the Effects of Occupational Licensing into Focus: Optician Licensing in the United States,” Eastern Economic Journal, 44, no. 1 (2018): 69-83. Survey data on government-issued occupational licensing are associated with an 11 percent differential in wages after controlling for other differences among of the applicants.48Morris Kleiner and Evgeny Vorotnikov, “Analyzing Occupational Licensing among the States,” Journal of Regulatory Economics 52, no. 2 (2017): 132–58. These wage premiums and barriers to entry reduce the equilibrium labor supply by an average of 17–27 percent.49Peter Blair and Bobby Chung, “How Much of a Barrier to Entry Is Occupational Licensing,” British Journal of Industrial Relations (forthcoming).

Since occupational licensing inspires diametrically opposed reactions among citizens, such regulations often become the topic of political campaigns. A researcher who used data on political spending in state- level elections finds that greater political spending by healthcare interest groups, mainly physicians and nurses, increased the probability that a state would maintain licensing laws that restrict practice.50Benjamin McMichael, “The Demand for Healthcare Regulation: The Effect of Political Spending on Occupational Licensing Laws,” Southern Economic Journal 84, no. 1 (2017): 297–316. This is interesting because it raises the question of why an organized group of individuals already inside a profession would actively seek regulatory barriers to the entry of new professionals. A part of the rationale for this behavior may be related to a paternalistic argument, according to which those already in the profession and government seek to keep out, in the best interest of the public, those attempting to enter the profession—though what constitutes the public’s best interest is hotly debated.51Adam Summers, “Occupational Licensing: Ranking the States and Exploring Alternatives” Policy Study #361, Reason Foundation, 2007.

Occupational regulation also commonly has spillover effects on other areas of interest such as student loans. Though these connections remain understudied, they imply a larger problem that needs to be addressed. Recently, the New York Times investigated and found that 19 states have begun suspending people’s professional licenses for unpaid student loans52Jessica Silver-Greenberg, Stacy Cowley, and Natalie Kitroeff, “When Unpaid Student Loan Bills Mean You Can No Longer Work,” New York Times, November 18, 2017.—loans that students are taking out to meet ever-increasing licensing education and experience requirements.

Licensing can be viewed not only as assurance that services meet quality and safety standards, but also as a signal that the licensed workers themselves offer a threshold level of quality and competence. This signal affects workers’ employment opportunities and employers’ willingness to hire a diverse set of workers. One 2018 study finds that the information and human capital content supplied by licenses enable firms to rely less on race and gender as predictors of worker productivity.53Blair and Chung, “Job Market Signaling.” The researchers find that licensing reduces the racial wage gap between white men and black men by 43 percent and the gender wage gap between white men and white women by 36–40 percent. Examining licensing regimes that include good moral character criteria, they find that a license tends to be a positive indicator of nonfelony status, particularly for black men.

It should be noted that additional work by the same authors agrees with previous literature about the costs associated with occupational licensing.54Blair and Chung, “How Much of a Barrier to Entry Is Occupational Licensing.” See also Kleiner and Soltas, “Welfare Analysis of Occupational Licensing.” It is important to always weigh the potential benefits of occupational licensing against its associated costs, which are well documented and understood. From a policy standpoint, there are likely less costly ways for black men to signal nonfelony status.

Visualization and Discussion

In light of the growing presence of occupational licensing within the US labor force, it is important to be able to visualize how licensing requirements have changed during recent decades. Since many occupational licensing conditions are set at the state level, the fees, education requirements, and examinations can vary drastically among states. Some occupations are subject to multiple levels of regulation. In addition to state-level requirements, there are also a variety of federal requirements, and individual municipalities may maintain their own standards and requirements that apply to workers who practice or operate in their territory. For example, the Federal Aviation Administration maintains federal-level licensing requirements for aviation maintenance technicians, which apply on a national scale.55Federal Aviation Administration, “Basic Requirements to Become an Aircraft Mechanic” https://www.faa.gov/mechanics/become/basic/. On the other end of the scale, tour guides are required to obtain a license in New York City, but there is no statewide requirement.56NYC Business, “Sightseeing Guide License” https://www1.nyc.gov/nycbusiness/description/sightseeing-guide-license.

This section considers only occupations that are subject to licensing, meaning that workers require government authorization to provide their services legally, in all or a subset of states. As an illustrative example, consider emergency medical technicians (a universally licensed occupation) and bartender. In every state, emergency medical technicians must have government permission to practice emergency medical response and to transport patients by ambulance to medical facilities, and it would be illegal for someone to perform these actions without authorization. On the other hand, in 38 states bartenders may obtain a voluntary certification to serve alcohol, but this certification is not required in any state and individuals can operate in this capacity without the certification.

Visualizing changes in occupational licensing requirements over time is difficult because, until recently, there was no consistent collection of state-level data that asked whether a person was subject to an occupational license or that surveyed known occupations for their entry requirements. Therefore, the discussion of data will be divided into three subsections. The first subsection identifies the growth in occupational licensing for low- and moderate-income professions between 1993 and 2012.57The section summarizes the findings of Edward Timmons et al., “Assessing Growth in Occupational Licensing of Low-Income Occupations: 1993–2012,” Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy 7, no. 2 (2018): 178–218. The second subsection examines the growth in the frequency and cost of occupational licensing for low-and middle-income professions between 2012 and 2017. Finally, the third subsection discusses current and future data sources and how changes in the Current Population Survey will affect how researchers and policymakers are able to address and analyze the effects of occupational licensing moving forward.

It is important to note that in this discussion of occupational licensing there is often a focus on low- and medium-income occupations. This focus reflects a limitation of the current literature due to data availability constraints. It is often argued, though, that these occupations are the ones that are most important to focus on, since licensing costs constitute a larger percentage of household income for lower- and middle-income households, and losing time to fulfill training and experience requirements can potentially disadvantage or harm households that rely on lower-paying occupations.

1993-2012

The study of occupational licensing drastically changed with the introduction of a publication from the Institute for Justice, titled License to Work (LTW). LTW presents the state-level occupational licensing requirements for 102 professions across all states and the District of Columbia.58Dick M. Carpenter II et al., License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, 1st ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, May 2012). It provided a benchmark for researchers to use as they sought to compare occupational licensing requirements at the state level. Before LTW was published in 2012, very little data about licensing at the national level was readily available.

In 2018, one of us (Edward Timmons) coauthored a study that used LTW to study economic mobility.59Timmons et al., “Assessing Growth in Occupational Licensing.” We used 1993 data from the Professional and Occupational Licensing Directory60David P. Bianco, ed., Professional and Occupational Licensing Directory: A Descriptive Guide to State and Federal Licensing, Registration, and Certification Requirements (Detroit: Gale Research, 1993). and compared these data to the data for occupations that were listed in the 2012 LTW. Our study became one of the first analyses of growth in low-income occupational licensing. Though it does not provide an exhaustive list of all licensed professions, our study’s comparison serves as an important basis point, offering a perspective from which to track the growth of licensing regulations over time.

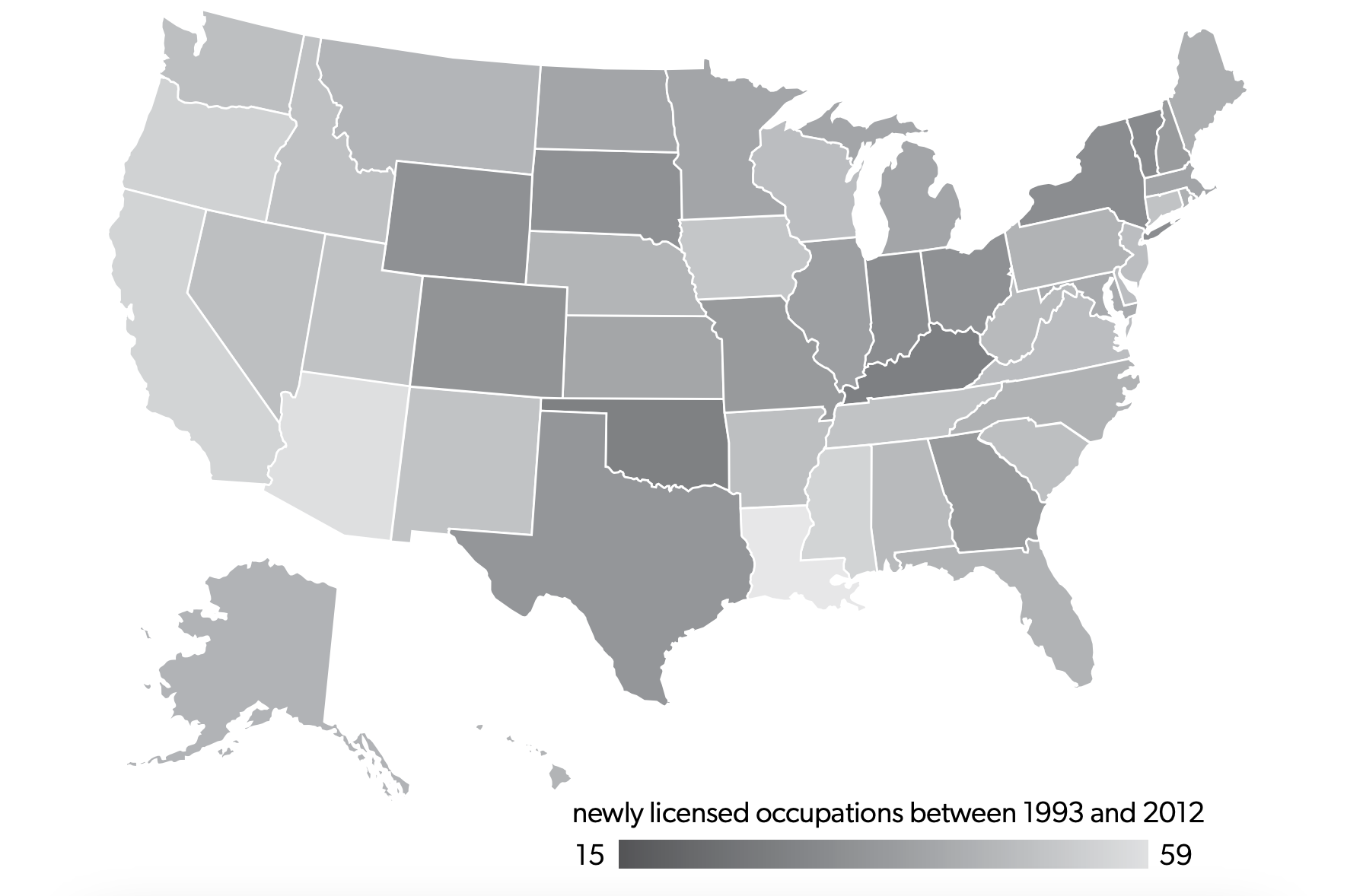

Figure 2 reproduces the original map of growth in licensed occupations from that 2018 study. Growth in the 1990s and shortly after the turn of the century was not limited to a single geographic region, and states differed drastically in the number of new occupational licenses they enacted—from a low of 15 in Kentucky to 59 in Louisiana. We also found that within the 1993–2012 period occupational licensing is associated with substantial negative effects on economic mobility within states.

Figure 2. Newly Licensed Occupations Between 1993 and 2012

2012-2017

License to Work was updated and rereleased in 2017.61Dick M. Carpenter II et al., License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, November 2017). Since the data collection and definition methodologies changed slightly between the 2012 and 2017 editions, there are limitations to the comparability of the aggregate state measures within these reports over time. Therefore, this subsection will discuss an overview of occupational licensing in 2017, as well as some observations about occupations for which data were collected consistently over this five-year period.

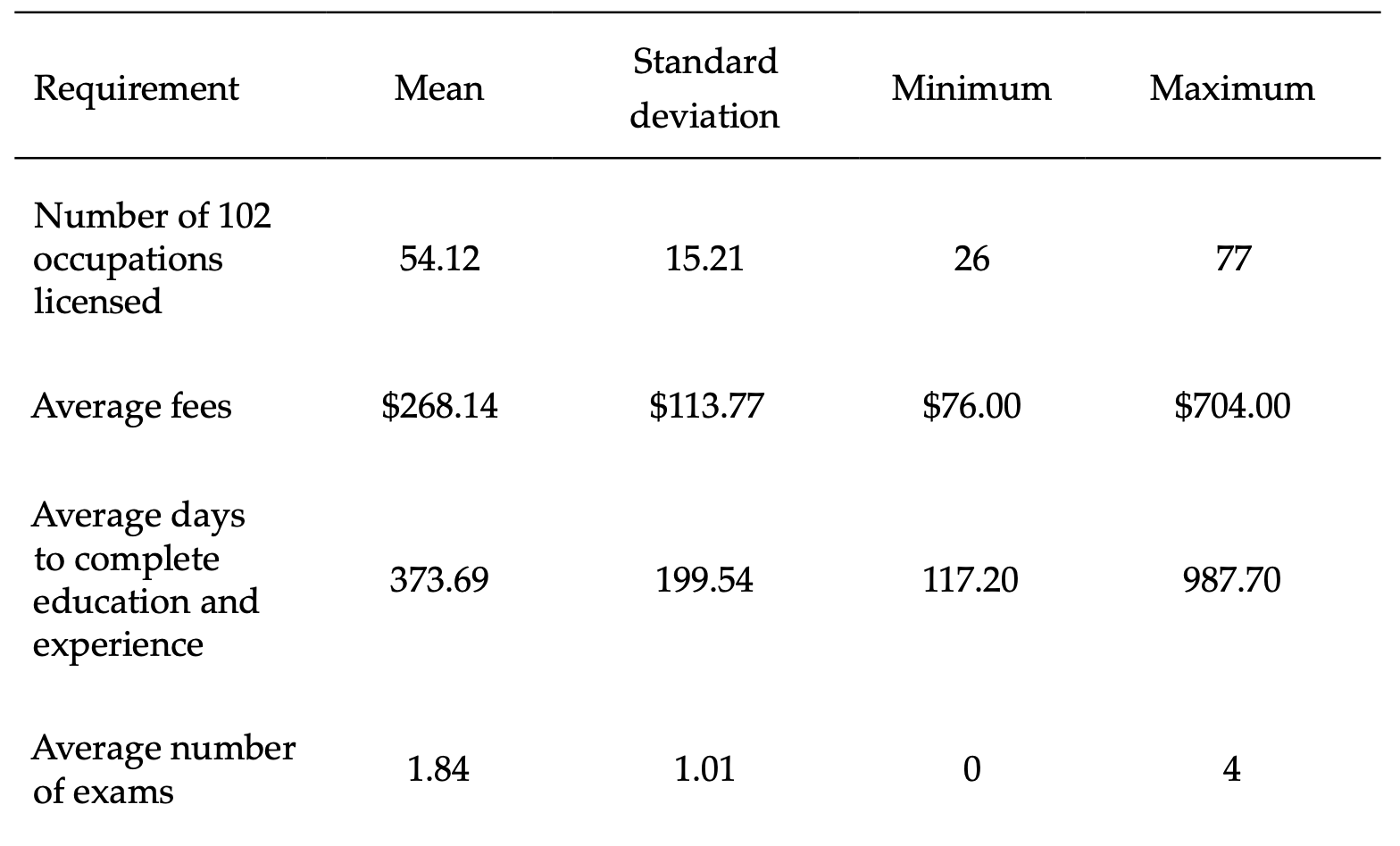

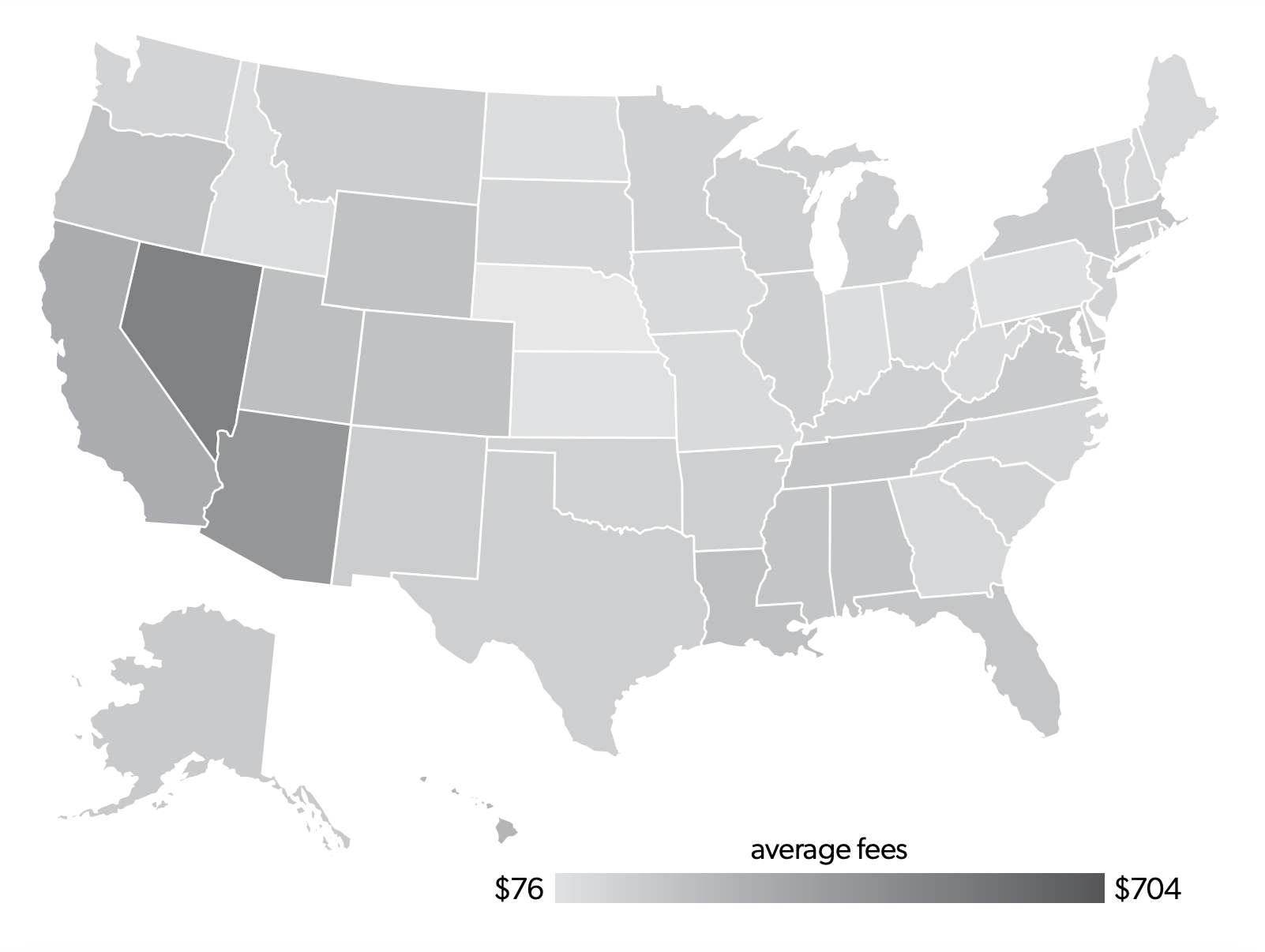

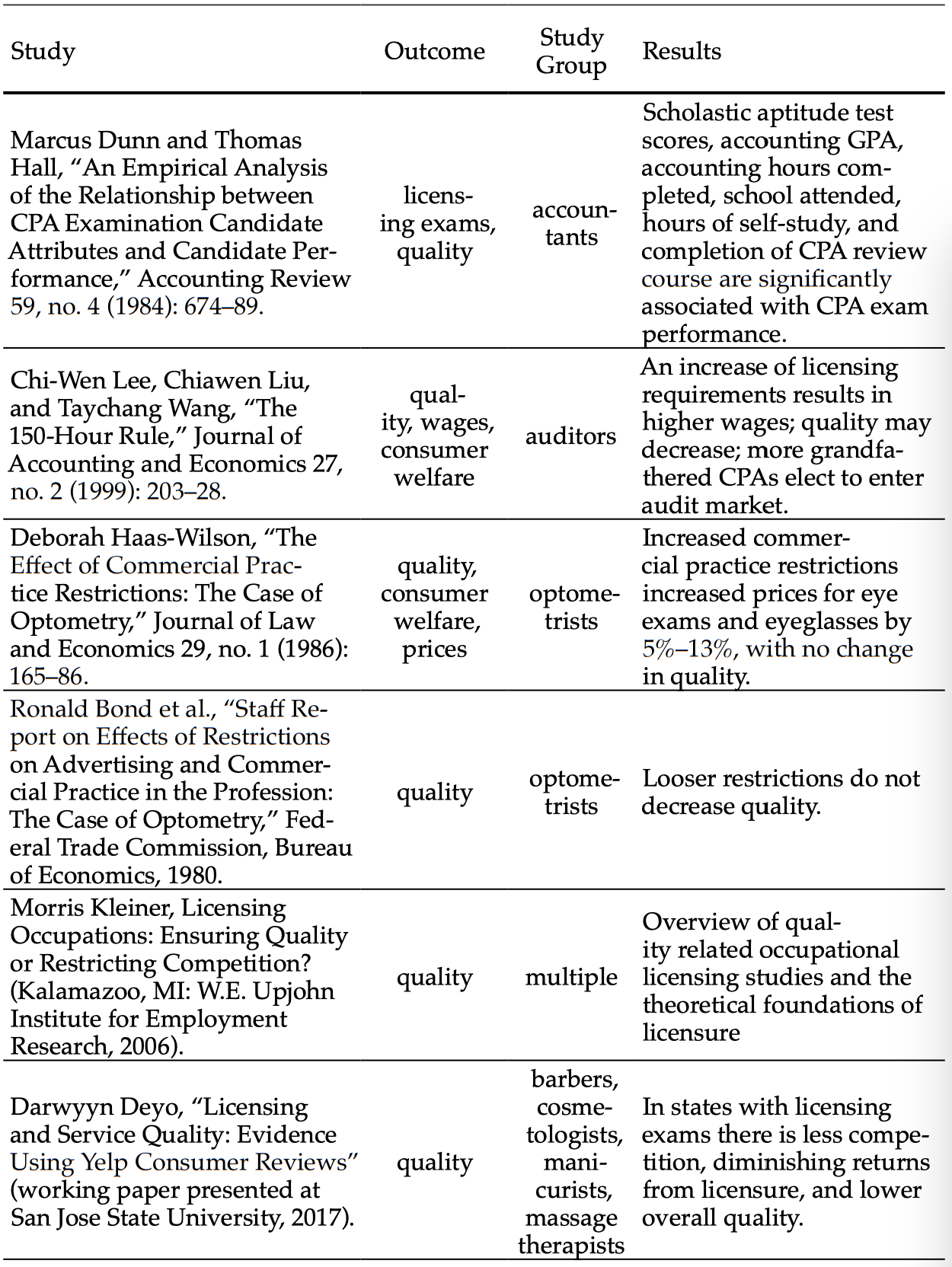

Table 1 presents summary statistics for occupational licensing costs across states for the 102 occupations included in the 2017 LTW update. One of the most notable and well-known costs of occupational licenses are fees. Comparing average fees is not the perfect way to capturing state variation, but it does provide a rough sketch of the regulatory environment. Figure 3 depicts the average fees to acquire a license in each state, and these vary drastically. Nevada is the most expensive state—on average, an occupational license costs $704. In Nebraska, the least expensive state, the average fee is $76. The average cost of a license across all states is $268.14; approximately two-thirds of states have averages within $113.77 above or below this average.

Table 1. Summary Statistics of 2017 Occupational Licensing Requirements

Figure 3. Average Fee to Obtain an Occupational License, 2017

Source: Dick M. Carpenter II et al., License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, November 2017).

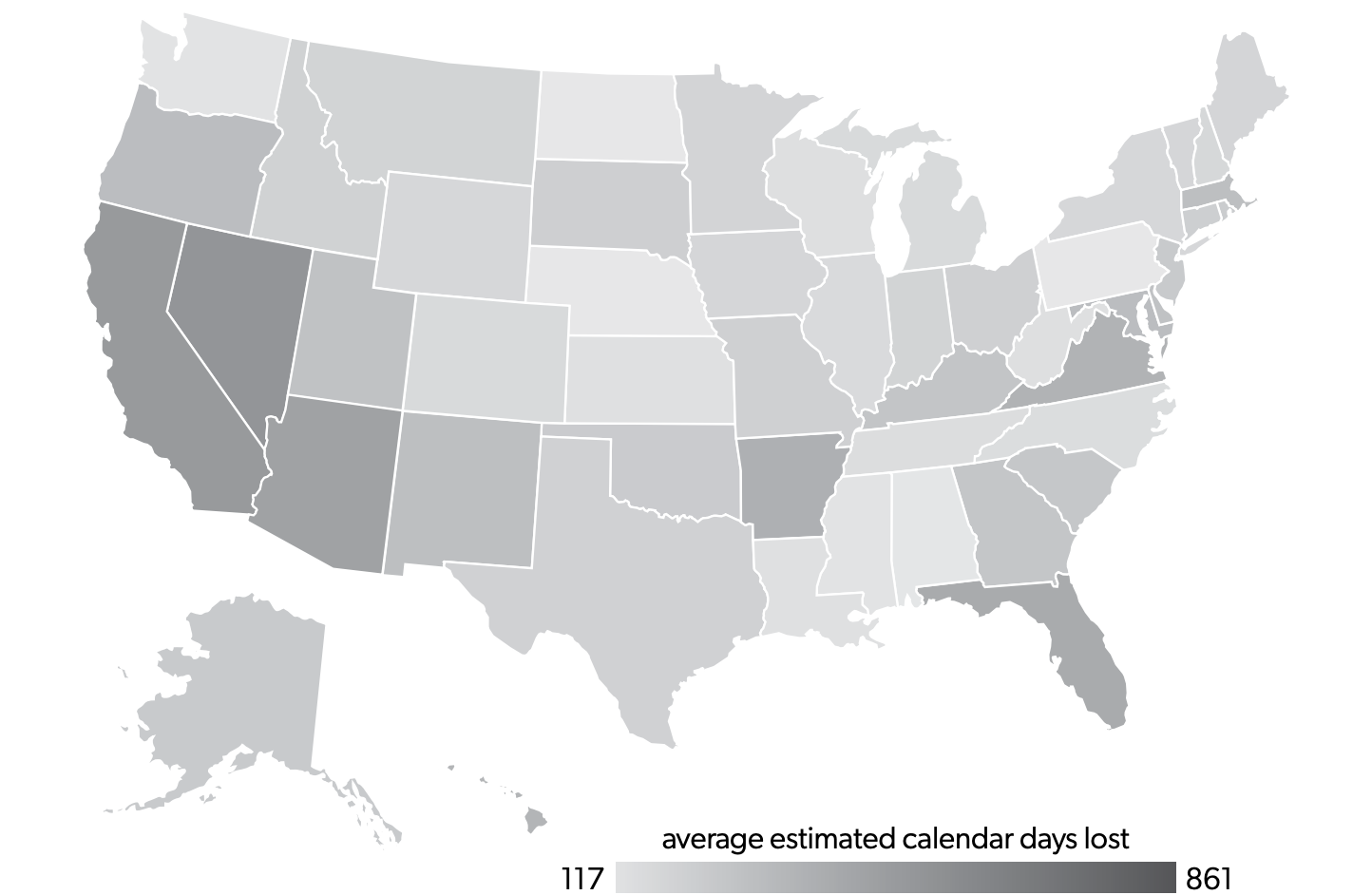

Table 1 also contains information on the number of the 102 occupations that are licensed within each state, the number of exams required to obtain a license, and the days required to complete mandated training and experience.

Figure 4 is a map depicting the length of time mandated to fulfill licensing requirements. One of the first interesting things to note is the similarities between average fees (figure 3) and education requirements (figure 4), since these measures tend to be correlated and if a state has a high cost in one, it often has a high cost in both. The amount of time needed to complete the education and experience requirements for a license in the United States, in 2017, averaged 373.69 days, or slightly over a year. The length of time necessary to fulfill these requirements can vary widely, from 117.20 days on average in Pennsylvania to 987.70 days in Hawaii (almost three years).

Figure 4. Average Number of Days to Complete Education and Experience Requirements for an Occupational License, 2017

Source: Dick M. Carpenter II et al., License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, November 2017).

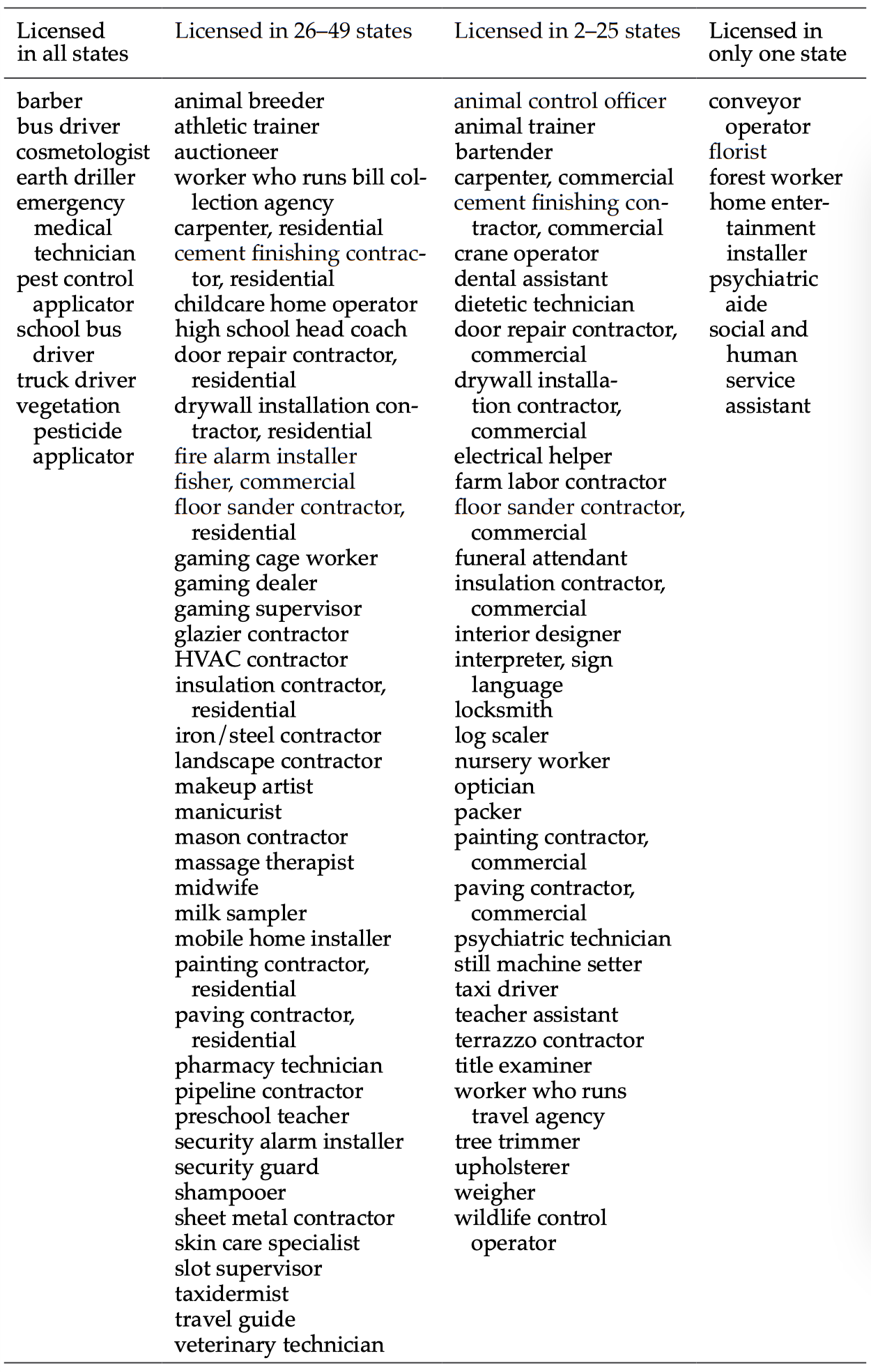

Professions that require licensing vary from state to state. For example, table 2 lists some of the many professions that require an occupational license. Some occupations are licensed in every state, such as those of bus drivers and emergency medical technicians. But many other licenses exist in only a selection of states. A few licensing regimes are entirely unique, in that only one state has enacted legislation to subject that profession to an occupational license. Some interesting examples include florists in Louisiana and home entertainment installers in Connecticut.

Since the 2012 edition of LTW differs in collection methodology from the 2017 edition, we can’t make direct comparisons of the state averages in fees or education requirements. It can be observed, however, that many professions saw an increase in the number of states that required occupational licensing between 2012 and 2017. For example, childcare workers now require a license in an additional 11 states, crane operators now require a license in an additional 14 states, and earth drillers are now required to obtain a license in every state—a license that involves costs ranging from $50 to $1,000 and up to six years of education requirements.

Table 2. Examples of Licensing Prevalence

Source: Dick M. Carpenter II et al., License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, November 2017).

Looking Forward

As of September 2020 there are a few great resources available that supply further information on occupational licensing. The Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation at Saint Francis University, founded in 2016, provides insight and data about the occupational licensing requirements for a variety of occupations across socioeconomic classes. Likewise, as noted previously, the Institute for Justice has published the License to Work study, which provides summary statistics about the licensing costs of 102 occupations across all states. Additionally, since 2015 the Current Population Survey has incorporated questions meant to identify individuals with professional certifications or occupational licenses. For instance, the survey asks respondents whether they currently have an active professional certification or a state or industry license, whether the certification or license was issued by a government agency (and at which level of government), and whether the certification or license is required for their job.

There are also a range of new federal data sources beyond the Cur- rent Population Survey available to students and policymakers.62Alex Bryson and Morris Kleiner. “Re-Examining Advances in Occupational Licensing Research: Issues and Policy Implications” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57, no. 4 (2019): 721-731. These include the Survey of Income and Program Participation, which in 2008 asked questions regarding professional certification and the Baccalaureate and Beyond which conducts four-year follow-up surveys on these 2008 degree recipients. The National Center for Education Statistics (within the US Department of Education) also provides the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study for 2012 and 2014. And the 2012 Education Longitudinal Study provides eight-year follow-ups on high school graduates from 2004.63Alex Bryson and Morris Kleiner, “Re-examining Advances in Occupational Licensing Research: Issues and Policy Implications,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57, no. 4 (2019): 721–31. These growing sources of data will assist legislatures to develop efficient policies and improve economic welfare.

Pathways for Reform

Momentum for reform of occupational licensing began to build up following the publication of Benjamin Shimberg, Barbara Esser, and Daniel Kruger’s Occupational Licensing in 1972.64Benjamin Shimberg, Barbara Esser, and Daniel Kruger, Occupational Licensing: Practices and Policies (Washington, DC: Public Affairs Press, 1972). The book reports the findings of a five-year study examining occupational licensing and notes a litany of problems with the status quo. Interest continued into 1980, when a conference organized by the American Enterprise Institute led to the publication of an edited volume on licensure.65Simon Rottenberg, ed., Occupational Licensure and Regulation (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1980). Interest from the academic community and the public policy community mostly languished for the next 20 years. Owing to a number of published works by economist Morris Kleiner (including three books), interest resumed in 2000. On the public policy front, the publication of the Obama White House report on licensing was also key.66White House, Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers, July 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/licensing_report_final_nonembargo.pdf.

From 1973 to 2013, only eight occupations were successfully delicensed.67Thornton and Timmons, “The De-licensing of Occupations.” From 2011 to 2016, twelve states attempted to delicense groups of occupations.68Robert Thornton, Edward Timmons, and Dante DeAntonio, “Licensure or License? Prospects for Occupational Deregulation,” Labor Law Journal 68, no. 1 (2017): 46–57. Perhaps the occupation for which deregulation efforts have been most successful is hair braiding. In 2005, twenty-nine states required hair braiders to obtain a full cosmetology license. As of September 2020, only seven states still maintain this requirement.69Updates on home page of “Braiding Freedom: A Project of the Institute for Jus- tice,” accessed February 22, 2020, http://braidingfreedom.com/ and Institute for Justice, accessed September 15, 2020, http://ij.org.

Instead of devoting efforts to delicensing individual occupations or groups of occupations, several states have successfully implemented comprehensive reforms. These reforms can be separated into three broad categories: (1) the Right to Earn a Living Act, (2) executive over- sight, and (3) mandatory sunset review.

The Right to Earn a Living Act (passed in Tennessee in 2016 and in Arizona in 2017)70S.B. 2469, 109th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Tennessee 2016); S.B. 1437, 53rd Leg., 1st Sess. (Arizona 2017). See also “Tennessee HB2201,” TrackBill, accessed February 22, 2020, https://trackbill.com/bill/tennessee-house-bill-2201-professions-and-occupations-as-enacted-enacts-the-right-to-earn-a-living-act-amends-tca-title-4-title-7-title-38-title-62-title-63-and-title-67/1238736/. recognizes that citizens have a fundamental right to work that takes precedence over existing occupational licensing law. It gives citizens the opportunity to sue the state if they believe that licensing laws are infringing on this fundamental right. In March 2017, the law resulted in a change in licensing requirements for behavioral health specialists in Arizona.71Angela Gonzales, “Goldwater Institute Helps Behavioral Health Counselors Continue Practicing in Arizona,” Phoenix Business Journal, November 7, 2017. As of September 2020, there have been no successful lawsuits in either state that have led to the complete removal of licensing laws.72Arizona also enacted a reform in 2019 that conditionally recognizes many licenses for new residents of the state. This reform did not change occupational licensing requirements for current residents, however.

Executive oversight initiates a review process by a state’s executive branch. Mississippi passed this type of reform in 2017.73S.B. 2489, 2017 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Mississippi 2017). An executive oversight law grants review power for all licensing rules to the state’s governor, attorney general, and secretary of state. If two of these three individuals object to a new licensing rule, the rule can be blocked or vetoed. As of September 2020, we are not aware of any instances in which Mississippi’s executive branch exercised this new authority to block licensing legislation.74The governor did veto legislation that would have tripled the experience requirement for real estate brokers in March 2018, but this was a more traditional veto of a pending bill rather than a rule change occurring outside the legislative process.

A number of states have instituted, by either legislation or executive order, a mandatory sunset review model. Under this type of reform, a mandatory review process is established that subjects existing occupational licensing to reviews. The frequency of these reviews varies depending on the state. Louisiana, Nebraska, and Oklahoma implemented this type of reform in 2018. Both Idaho and Ohio implemented it in 2019.75One issue with the sunset process is that it is subject to executive review. A great example of a sunset recommendation being overturned occurred with plumbers in Texas in June 2019. See Elizabeth Byrne, “Abbott Extends State Plumbing Board until 2021 after Legislature Abolished It,” Texas Tribune, June 13, 2019.

There is a fourth type of reform that, as of early 2020, has not been implemented in any state. In October 2018, Governor Susana Martinez of New Mexico issued an executive order permitting consumers to seek service from unlicensed professionals.76Office of the New Mexico Governor, “Martinez Issues Executive Order Implementing Comprehensive Occupational Licensing Reform,” KRWG, October 3, 2018. Essentially, the order would transform existing occupational licenses into voluntary certification. Courts made the determination that legislation would be needed to make the change, and no such legislation has yet been proposed in New Mexico.77Ellen Marks, “Licensing Reforms Require Legislative Approval,” Albuquerque Journal, October 23, 2018. Legislation has been put forward in West Virginia,78H.B. 2697, 2019 Leg., Reg. Sess. (West Virginia 2019). but (as of September 2020) has not been approved.

It is too early to surmise what type of reform is most effective. Up until the past five years, the general trend nationwide has been an increase in the scale and scope of occupational licensing. A number of states are currently engaged in reform efforts and soon there will be data available to evaluate the effectiveness of these different types of reform to inform policymakers and provide a template for implementing future reform.

Appendix: Table of Occupational Licensing Studies

Quality Studies

Wage Studies

Labor Supply Studies

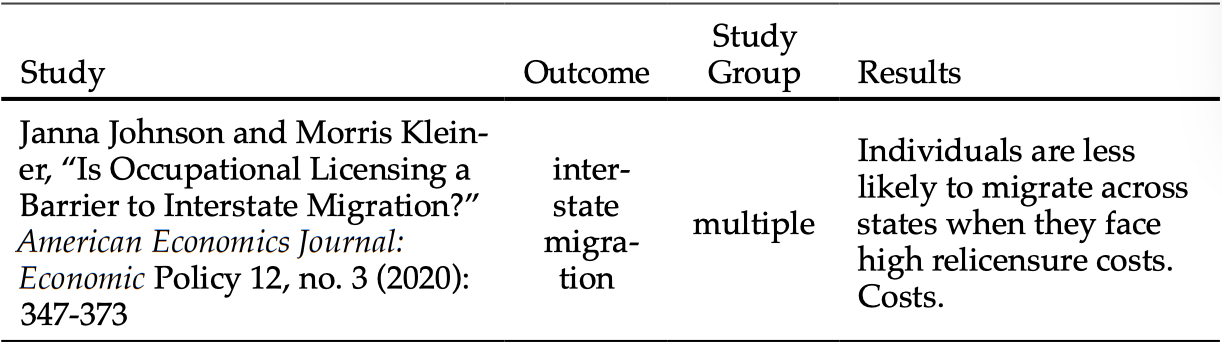

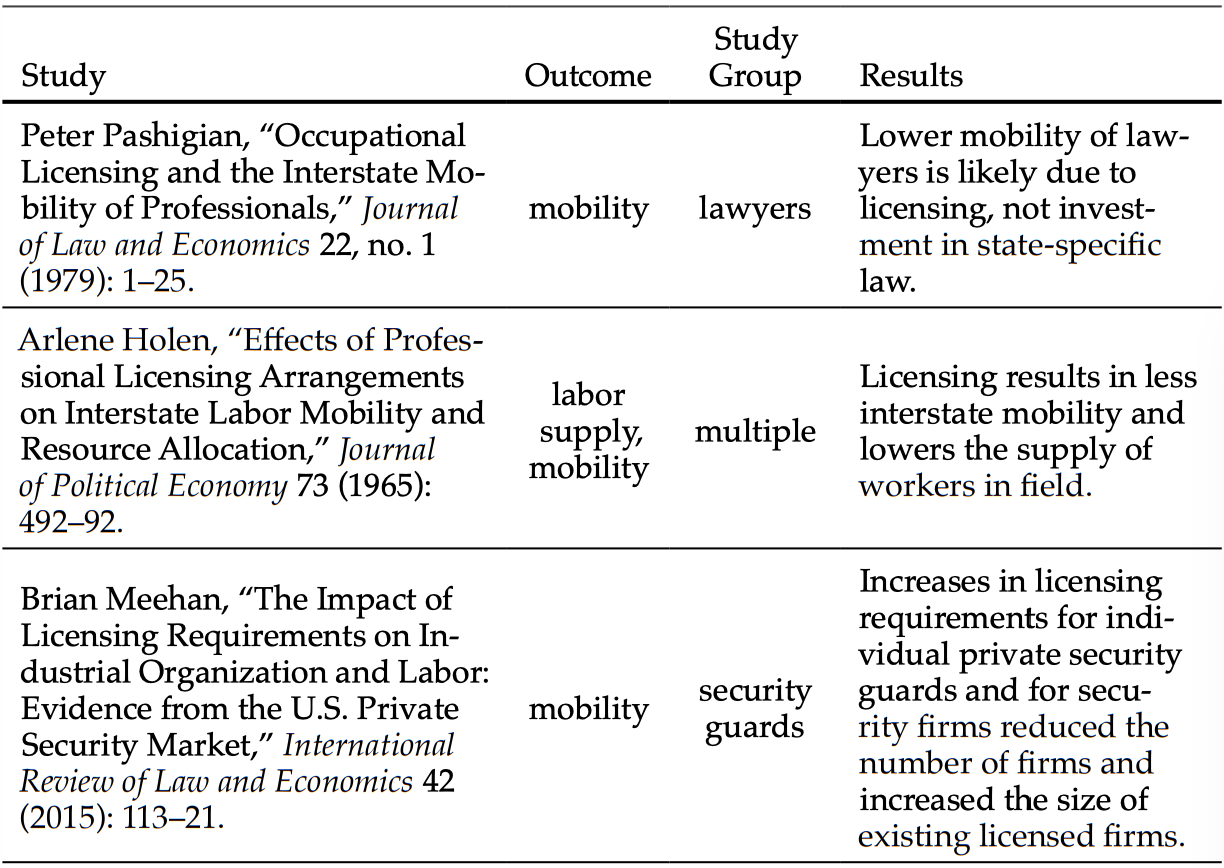

Migration and Mobility Studies

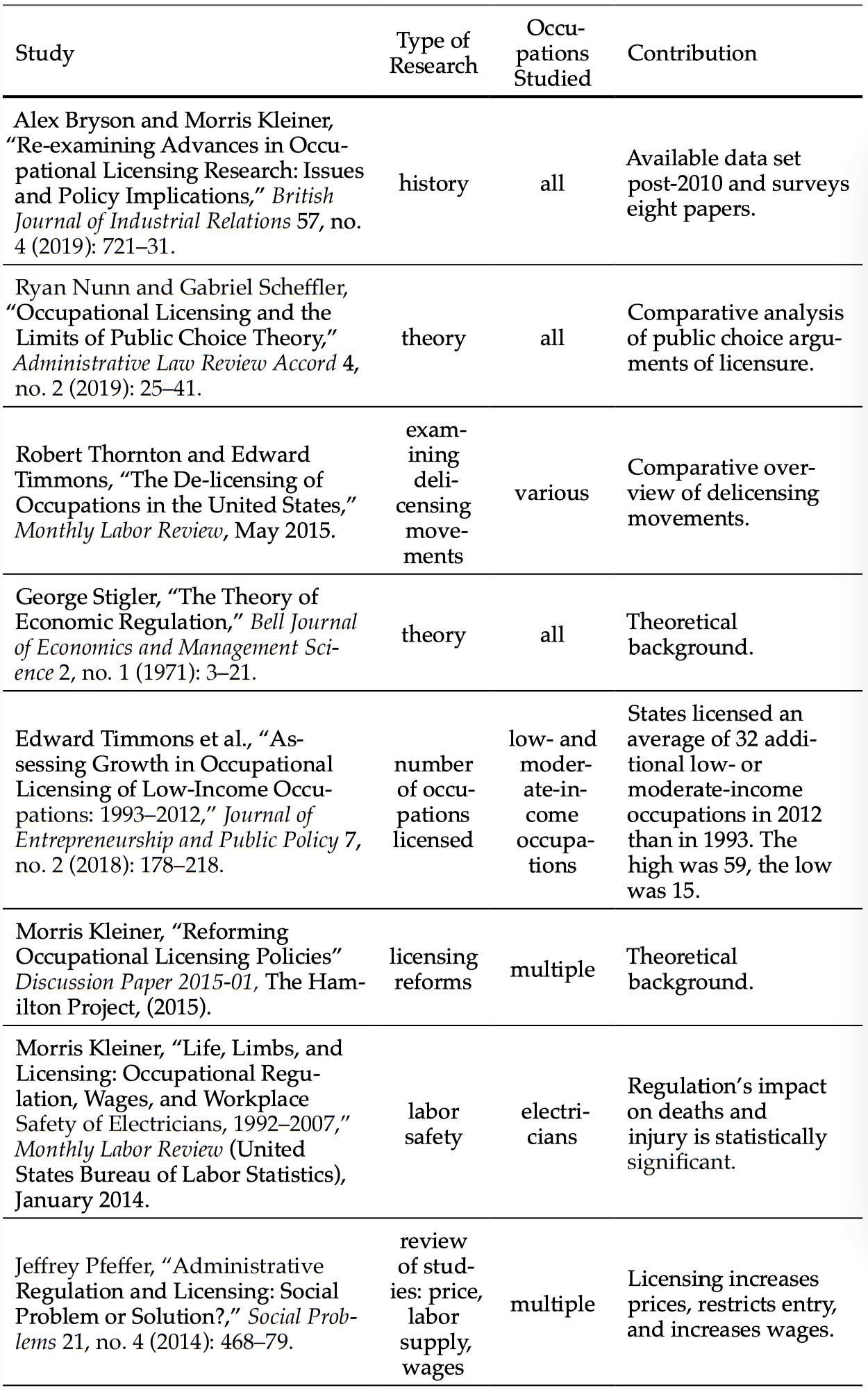

Entrepreneurship Studies

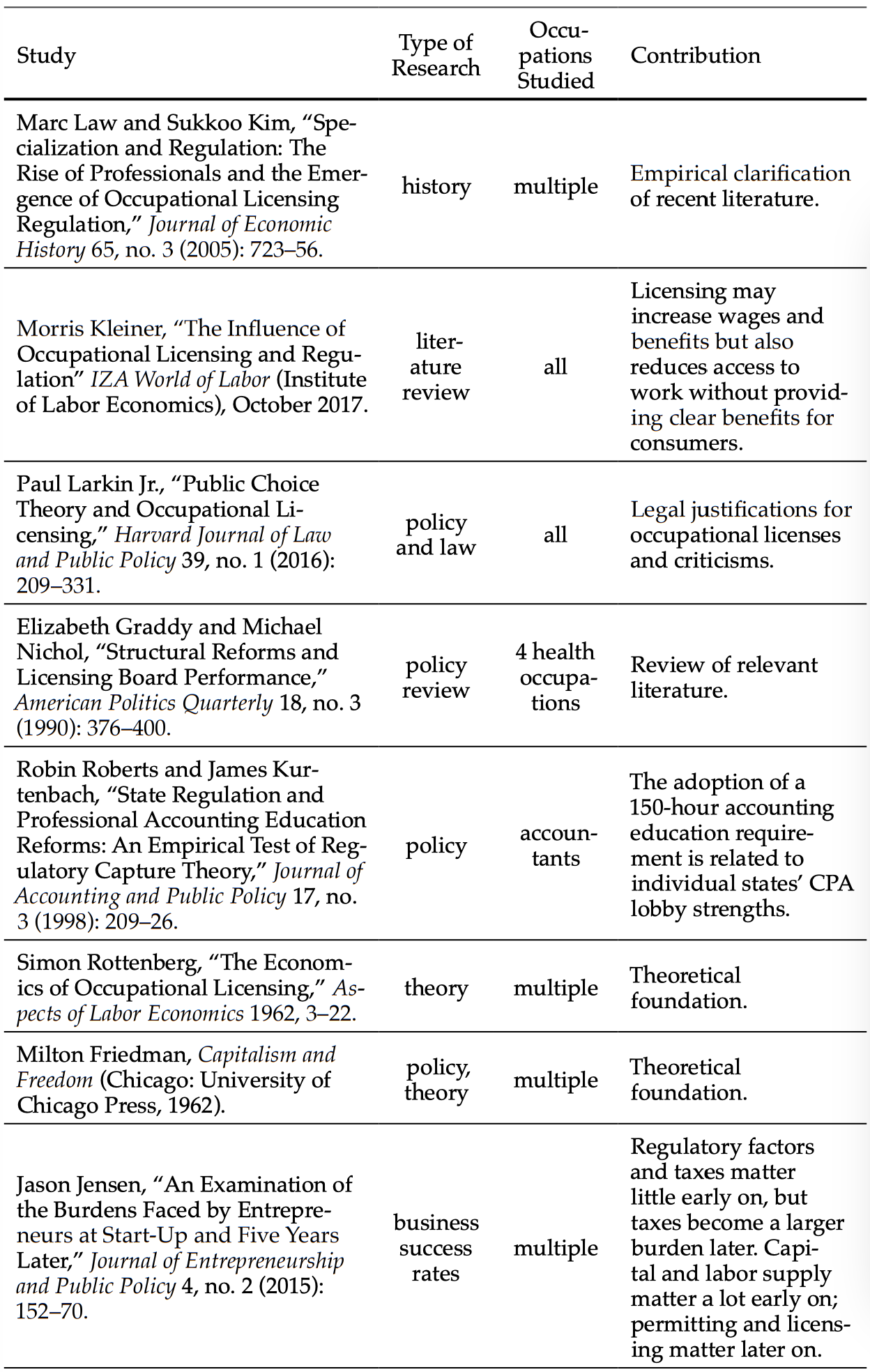

Summary Literature

References

Adams, A. Frank, John Jackson, and Robert Ekelund. “Occupational Licensing in a ‘Competitive’ Labor Market: The Case of Cosmetology.” Journal of Labor Research 23, no. 2 (2002): 261–78.

Akerlof, George. “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84, no. 3 (1970): 488–500.

Arrow, Kenneth. Essays in the Theory of Risk-Bearing (United States: Markham, 1971).

Barbering/Barber Career Program Tuition & Fees Comparison. College Tuition Compare. https://www.collegetuitioncompare.com/compare/tables/vocational-program/barbering-barber/.

Bianco, David P. ed. Professional and Occupational Licensing Directory: A Descriptive Guide to State and Federal Licensing, Registration, and Certification Requirements (Detroit: Gale Research. 1993).

Blair, Peter and Bobby Chung. “How Much of a Barrier to Entry Is Occupational Licensing.” British Journal of Industrial Relations (forthcoming).

Blair, Peter and Bobby Chung. “Job Market Signaling through Occupational Licensing.” (NBER Working Paper No. 24791. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. 2018).

“Braiding Freedom: A Project of the Institute for Justice.” Accessed February 22, 2020. http://braidingfreedom.com/ and Institute for Justice. Accessed September 15, 2020. http://ij.org.

Briggs, Zack. “Bill Would Abolish Arkansas Barber Board, No License or Education Required to Cut Hair.” KATV. March 6, 2019.

Bryson, Alex and Morris Kleiner. “Re-Examining Advances in Occupational Licensing Research: Issues and Policy Implications.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57, no. 4 (2019): 721-731.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Barbers, Hairstylists, and Cosmetologists.” Occupational Outlook Handbook. Last modified September 1, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/personal-care-and-service/barbers-hairstylists-and-cosmetologists.htm.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers, 2017.” BLS Reports. Report 1072. March 2018. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2017/home.htm.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Data on Certifications and Licenses.” Last modified January 22, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/cps/certifications-and-licenses.htm.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.”

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Union Members Summary.” News release. January 22, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm.

Byrne, Elizabeth. “Abbott Extends State Plumbing Board until 2021 after Legislature Abolished It.” Texas Tribune. June 13, 2019.

Carpenter, Dick M. II et al. License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing. 1st ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice. May 2012).

Carpenter, Dick M. II et al. License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing. 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice. November 2017).

Carpenter, Dick M. III, Lisa Knepper, Kyle Sweetland, and Jennifer McDonald. “The Continuing Burden of Occupational Licensing in the United States.” Economic Affairs 38, no. 3 (2018): 380-405.

Carroll, Sidney and Robert Gaston. “Occupational Licensing and the Quality of Service: An Overview.” Law and Human Behavior 7, no. 2–3 (1983): 139–46.

Chao, Yüan-ling. Late Imperial China: A Study of Physicians in Suzhou, 1600–1850 (New York: Peter Lang. 2009).

Connor, Camille. “Barbers, Cosmetologists against Texas Bill That Would Do Away with Licenses.” News Channel 6. March 13, 2019.

Council on Licensure, Enforcement & Regulation. “Sunrise, Sunset and Agency Audits.” Accessed February 22, 2020. https://www.clearhq.org/page-486181.

Dent v. West Virginia. 129 U.S. 114 (1889).

Duffy, Thomas. “The Flexner Report—100 Years Later.” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 84, no. 3 (2011): 269–76.

Elman, Benjamin. Civil Examinations and Meritocracy in Late Imperial China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 2013).

Farronato, Chiara et al. “Consumer Protection in an Online World: An Analysis of Occupational Licensing.” (NBER Working Paper No. 26601. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. 2020).

Federal Aviation Administration. “Basic Requirements to Become an Aircraft Mechanic.” https://www.faa.gov/mechanics/become/basic/.

Friedman, Milton. Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1962).

Frizzell, Casey. “Barbers Upset with Cuts Proposed Bill Would Make in Arkansas.” 5 News. March 7, 2019.

Gius, Mark. “The Effects of Occupational Licensing on Wages: A State-Level Analysis.” International Journal of Applied Economics 12. no. 20 (2016): 30–45.

Gonzales, Angela. “Goldwater Institute Helps Behavioral Health Counselors Continue Practicing in Arizona.” Phoenix Business Journal. November 7, 2017.

H.B. 2697. 2019 Leg. Reg. Sess. (West Virginia 2019).

Holen, Arlene. “The Economics of Dental Licensing.” Arlington, VA: Public Research Institute of the Center for Naval Analysis. 1978.

Kleiner, Morris and Alan Krueger. “The Prevalence and Effects of Occupational Licensing.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48, no. 4 (2010): 1–12.

Kleiner, Morris and Evan Soltas. “A Welfare Analysis of Occupational Licensing in U.S. States” (NBER Working Paper No. 26383. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. 2019).

Kleiner, Morris and Evgeny Vorotnikov. “Analyzing Occupational Licensing among the States.” Journal of Regulatory Economics 52, no. 2 (2017): 132–58.

Kleiner, Morris and Kyoung Park. “Battles among Licensed Occupations: Analyzing Government Regulations on Labor Market Outcomes for Dentists and Hygienists.” (NBER Working Paper No. 16560. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. 2010).

Kleiner, Morris and Robert Kudrle. “Does Regulation Affect Economics Outcomes? The Case of Dentistry.” Journal of Law and Economics 43, no. 2 (2000): 547–82.

Kleiner, Morris. “Occupational Licensing.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14, no. 4 (2000): 189–202.

Kleiner, Morris. Licensing Occupations: Ensuring Quality or Restricting Competition? (Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. 2006).

Larkin, Paul Jr. “Public Choice Theory and Occupational Licensing.” Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 39, no. 1 (2016): 209–331.

Law, Marc and Sukkoo Kim. “Specialization and Regulation: The Rise of Professionals and the Emergence of Occupational Licensing Regulation.” Journal of Economic History 65, no. 3 (2005): 723–56.

Leland, Hayne. “Quacks, Lemons, and Licensing: A Theory of Minimum Quality Standards.” Journal of Political Economy 87, no. 6 (1979): 1328–46.

Marks, Ellen. “Licensing Reforms Require Legislative Approval.” Albuquerque Journal. October 23, 2018.

McMichael, Benjamin. “The Demand for Healthcare Regulation: The Effect of Political Spending on Occupational Licensing Laws.” Southern Economic Journal 84, no. 1 (2017): 297–316.

Meehan, Brian et al. “The Effects of Growth in Occupational Licensing on Intergenerational Mobility.” Economics Bulletin 39, no. 2 (2019): 1516–28.

Nunn, Ryan and Gabriel Scheffler. “Occupational Licensing and the Limits of Public Choice Theory.” Administrative Law Review Accord 4, no. 2 (2019): 25–41.

NYC Business. “Sightseeing Guide License.” https://www1.nyc.gov/nycbusiness/description/sightseeing-guide-license.

Office of the New Mexico Governor. “Martinez Issues Executive Order Implementing Comprehensive Occupational Licensing Reform.” KRWG. October 3, 2018.

Olson, Mancur. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965).

Perloff, Jeffrey. “The Impact of Licensing Laws on Wage Changes in the Construction Industry.” Journal of Law and Economics 23, no. 2 (1980): 409–28.

Plemmons, Alicia. “Occupational Licensing Effects on Firm Entry and Employment.” (Working Paper no. 2019.008. Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University. 2019).

Ross, John K. “The Inverted Pyramid: 10 Less Restrictive Alternatives to Occupational Licensing.” (report, Institute for Justice, November 2017).

Rottenberg, Simon. ed. Occupational Licensure and Regulation (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute. 1980).

S.B. 1437. 53rd Leg. 1st Sess. (Arizona 2017).

S.B. 2469. 109th Gen. Assemb. Reg. Sess. (Tennessee 2016).

S.B. 2489. 2017 Leg. Reg. Sess. (Mississippi 2017).

Shapiro, Carl. “Investment, Moral Hazard, and Occupational Licensing.” Review of Economic Studies 53, no. 5 (1986): 843–62.

Shimberg, Benjamin, Barbara Esser, and Daniel Kruger. Occupational Licensing: Practices and Policies (Washington, DC: Public Affairs Press, 1972).

Silver-Greenberg, Jessica, Stacy Cowley, and Natalie Kitroeff. “When Unpaid Student Loan Bills Mean You Can No Longer Work.” New York Times. November 18, 2017.

Smith. Chapter X: On Wages and Profit in the different Employments of Labor and Stock. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. (1776)

Stigler, George J. “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 2, no. 1 (1971): 3–21.

Summers, Adam. “Occupational Licensing: Ranking the States and Exploring Alternatives.” Policy Study #361. Reason Foundation. 2007.

“Tennessee HB2201.” TrackBill. Accessed February 22, 2020. https://trackbill.com/bill/tennessee-house-bill-2201-professions-and-occupations-as-enacted-enacts-the-right-to-earn-a-living-act-amends-tca-title-4-title7-title-38-title-62-title-63-and-title-67/1238736/.

The Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation. Barber Licensing Data. https://csorsfu.com/.

Thierer, Adam et al. “How the Internet, the Sharing Economy, and Reputational Feedback Mechanisms Solve the ‘Lemons Problem.’” (Mercatus Working Paper. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Arlington, VA. May 2015).

Thornton, Robert and Edward Timmons. “The De-licensing of Occupations in the United States.” Monthly Labor Review. May 2015.

Thornton, Robert, Edward Timmons, and Dante DeAntonio. “Licensure or License? Prospects for Occupational Deregulation.” Labor Law Journal 68, no. 1 (2017): 46–57.

Timmons, Edward and Anna Mills. “Bringing the Effects of Occupational Licensing into Focus: Optician Licensing in the United States.” Eastern Economic Journal. 44, no. 1 (2018): 69-83.

Timmons, Edward and Robert Thornton, “The Effects of Licensing on the Wages of Radiologic Technologists.” Journal of Labor Research 29, no. 4 (2008): 333–46.

Timmons, Edward and Robert Thornton. “Licensing One of the World’s Oldest Professions: Massage.” Journal of Law and Economics. 56, no. 2, (2013): 371-88.

Timmons, Edward and Robert Thornton. “The Licensing of Barbers in the USA.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 48, no. 4 (2010):740-57. December 2010.

Timmons, Edward et al. “Assessing Growth in Occupational Licensing of Low-Income Occupations: 1993–2012.” Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy 7, no. 2 (2018): 178–218.

Tullock, Gordon. “The Transitional Gains Trap.” Bell Journal of Economics 6, no. 2 (1975): 671–78.

White House. Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers. July 2015. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/licensing_report_final_nonembargo.pdf.

Table of Contents

- Regulation and Entrepreneurship: Theory, Impacts, and Implications

- Regulation and the Perpetuation of Poverty in the US and Senegal

- Social Trust and Regulation: A Time-Series Analysis of the United States

- Regulation and the Shadow Economy

- An Introduction to the Effect of Regulation on Employment and Wages

- Occupational Licensing: A Barrier to Opportunity and Prosperity

- Gender, Race, and Earnings: The Divergent Effect of Occupational Licensing on the Distribution of Earnings and on Access to the Economy

- How Can Certificate-of-Need Laws Be Reformed to Improve Access to Healthcare?

- Land Use Regulation and Housing Affordability

- Building Energy Codes: A Case Study in Regulation and Cost-Benefit Analysis

- The Tradeoffs between Energy Efficiency, Consumer Preferences, and Economic Growth

- Cooperation or Conflict: Two Approaches to Conservation

- Retail Electric Competition and Natural Monopoly: The Shocking Truth

- Governance for Networks: Regulation by Networks in Electric Power Markets in Texas

- Net Neutrality: Internet Regulation and the Plans to Bring It Back

- Unintended Consequences of Regulating Private School Choice Programs: A Review of the Evidence

- “Blue Laws” and Other Cases of Bootlegger/Baptist Influence in Beer Regulation

- Smoke or Vapor? Regulation of Tobacco and Vaping

- Moving Forward: A Guide for Regulatory Policy