Regulation, while usually well intended, can have detrimental effects on overall economic activity because it creates barriers to entry for firms and workers and because it hinders economic activity more generally. Economies that are more heavily regulated tend to have lower rates of new firm starts, lower levels of overall employment, and lower economic growth overall.1Djankov et. Al (2002), Klapper, Laeven, Rajan (2006) Simeon Djankov, Raphael La Porta, Florenzio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer, (2002). “The Regulation of Entry,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (2002), No. 1: 1-37; Simeon Djankov, Caralee McLiesh, and Rita Ramalho, “Regulation and Growth,” Economics Letters, 92 (2006): 395-401; Leora Klapper, Luc Laeven, and Raghuram Rajan, “Entry regulation as a barrier to Entrepreneurship,” Journal of Financial Economics , 82 (2006), No:3: 591-629; James Bailey and Diana Thomas, “Regulating Away Competition: the effect of regulation on entrepreneurship and employment,” Journal of Regulatory Economics, 52 (2017): 237-254. In addition, regulation has been shown to have disproportionately negative effects on low-income households and workers.2Diana W. Thomas, “Regressive Effects of Regulation,” Public Choice 180, no. 1/2 (2019): 1–10. Price increases resulting from regulation are borne disproportionately by low-income consumers,3Dustin Chambers, Courtney A. Collins, and Allan Krause, “How Do Federal Regulations Affect Consumer Prices? An Analysis of the Regressive Effects of Regulation,” Public Choice 180, no. 1/2 (2019): 57–90. lower-wage professions tend to suffer decreasing wages as a result of regulation,4James Bailey, Diana W. Thomas, and Joseph Anderson, “Regressive Effects of Regulation on Wages,” Public Choice 180, no. 1/2 (2019): 91–103. and states with higher levels of regulation tend to have higher levels of poverty.5Dustin Chambers, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Laura Stanley, “Barrier to Prosperity: The Harmful Impact of Entry Regulations on Income Inequality,” Public Choice 180, no. 1/2 (2019): 165–90. Given the differential effects of regulation on different socioeconomic classes, an obvious question is whether regulation has differential and potentially negative effects on different genders and races as well. In this chapter, we explore this question in more detail by reviewing the literature on occupational licensing—a type of labor-market regulation—and its effect on gender and race wage gaps.

Occupational Licensing, Gender, and Race

More than a quarter of all workers employed in the United States in 2017 held a certificate or an occupational license.6Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,” last modified January 22, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat49.htm. This number has increased dramatically since the 1950s, when roughly 5 percent of the employed were licensed or certified.7Ryan Nunn, Occupational Licensing and American Workers (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2016). As a result of this trend, occupational licensing has become an important institution in the analysis of labor markets.

Occupational licensing is a government credential that an individual is required to acquire to legally work for pay in an occupation. It can be required by a local, state, or federal government, but state requirements are the most common in the US. Licensure may entail receiving specific training, passing exams, completing continuing education requirements, and paying certification fees, and licensing requirements often contain some morality clause. The main rationale for a license is to protect the health and safety of customers and to ensure a high quality of service. However, the number of worker types covered by licensing regulation has increased dramatically since the 1950s, and states now require licenses not only for workers in traditional health and safety fields, such as doctors and electricians, but for more and more categories of workers, such as interior designers and travel agents.8For more information on this point, see chapter 7 in this volume by Alicia Plemmons and Edward Timmons.

Traditionally, economic theory suggests that occupational licensing increases barriers to entry and results in increased, positive economic profit for incumbents in the labor market whose supply is now restricted.9Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962). Additionally, the literature on rent-seeking suggests that intra-industry rent-seeking can result in a skewed distribution of regulatory rents, where some suppliers benefit at the expense of others.10Robert B. Ekelund and Robert D. Tollison, “The Interest-Group Theory of Government,” in The Elgar Companion to Public Choice, ed. William F. Shughart II and Laura Razzolini (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2001). The implication of these theoretical contributions for the analysis of the effect of occupational licensing on wages is that, depending on the licensing institutions, distributional consequences may differ.

On the whole, Maury Gittleman, Mark Klee, and Moriss Kleiner find that credentialed (licensed or certified) workers earn on average 5.7 percent more than noncredentialled workers, are more likely to be employed, and are more likely to receive employer-provided health insurance.11Maury Gittleman, Mark A. Klee, and Moriss M. Kleiner, “Analyzing the Labor Market Outcomes of Occupational Licensing,” Industrial Relations 57, no. 1 (2018): 57–100. In addition, Gittleman, Klee, and Kleiner find that licensing does not seem to have an effect on wage inequality. However, other researchers have found that countries with more stringent entry regulations for businesses do have increased income inequality (Chambers, McLaughlin, and Stanley 2019). Occupational licensure is one example of an entry regulation, though one that these researchers did not examine specifically.12Dustin Chambers, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Laura Stanley, “Barrier to Prosperity: The Harmful Impact of Entry Regulations on Income Inequality,” Public Choice 180, no. 1/2 (2019): 165–90. The expanding number of occupations requiring licensing has the potential to be regressive in nature, however, by providing greater benefits to those who are already wealthier. While a credential increases wages for those employed, it also has the potential to change worker selection into a field because of the higher barrier to entry and, as a result, it reduces overall employment in that field.13Morris M. Kleiner and Evan J. Soltas, “A Welfare Analysis of Occupational Licensing in U.S. States” (NBER Working Paper No. 26383, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, October 2019).

Occupational Licensing and Gender

Gender differences in compensation are measured in terms of the widely discussed gender wage gap. In 2014, full-time female workers earned on average 81.1 percent of male weekly earnings on an annual basis.14Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2018,” BLS Report 1083. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-earnings/2018/pdf/home.pdf. This highly cited statistic continues to cause outrage among politicians and the public, and has been used as a justification for legislation requiring firms to release earnings data and prohibiting employers from retaliating against employees who disclose their own wages or inquire about their employer’s wage practices.

In historical comparison, the earnings gap has decreased significantly since 1979, the first year for which comparable earnings data area available. Women earned on average 60 cents on the male dollar between 1950 and 1980, but the earnings ratio began to increase in the late 1970s and convergence has been significant since then. Women’s weekly earnings ratio increased from 61.0 percent to 76.5 percent of male workers’ between 1978 and 1999,15Francis D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, “Gender Differences in Pay,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14, no. 4 (2000): 70. but progress has been slower and more differentiated since.

Economists have studied the wage gap and potential explanations for it extensively over the past several decades, and the most recent comprehensive study by Blau and Kahn (2017) suggests that up to 62 percent of the gap can now be explained.16Francis D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations,” Journal of Economic Literature 55, no. 3 (2017): 789–865. In this study, economists Francis Blau and Lawrence Kahn examine traditional measures of human capital, such as education and experience, as well as additional controls for industry, occupation, and union coverage. The results for their full specification suggests that females earned 91.6% of male earnings in 2010, which leaves a gap of 8.4 cents between male and female earnings.17Blau and Kahn, “Gender Wage Gap,” 797. This remaining gap could be the result of either unobserved differences between male and female workers (statistical discrimination) or the discriminatory tastes of coworkers, customers, and employers.18Gary S. Becker, The Economics of Discrimination (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957).

Claudia Goldin argues persuasively that the remaining female-to-male earnings gap comes from within-occupation differences in earnings rather than from between-occupation differences.19Claudia Goldin, “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter,” American Economic Review 104, no. 4 (2014): 1091–119. Put differently, it is not the systematic choice of lower-paying occupations on the part of women that drives the gender wage gap, but instead earnings differences within occupations. Across different occupations, women in the same occupation systematically earn less than their male counterparts, even when researchers control for education and experience.

Taking a closer look at the pharmacy profession, which has a comparatively low wage gap, Goldin and her coauthor, Lawrence Katz, suggest that growth of pharmacy employment in retail chains and hospitals and the decline of independent pharmacies over the past half century has created an environment of greater substitutability among pharmacists and subsequently greater linearity in pay (that is, a reduced penalty for part-time work) in which women, who are more likely to work part time, get paid the same as men, who have more traditional work schedules.20Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, “A Most Egalitarian Profession: Pharmacy and the Evolution of a Family-Friendly Occupation,” Journal of Labor Economics 34, no. 3 (July 2016): 705–46.

In their discussion of this relatively egalitarian profession, Goldin and Katz highlight two particular factors that have resulted in greater substitutability of individual pharmacists: First, greater use of information technology and more pervasive prescription drug insurance have enhanced the ability of pharmacists to hand off clients. Second, the standardization of pharmacy products and the reduction of the prevalence of compounding by individual pharmacies have reduced the importance of the idiosyncratic expertise and talent of particular pharmacists. As a result, consumer preferences for particular pharma- cists have decreased and pharmacists have become more substitutable. At the same time, the shift toward larger-scale retailing of drugstores facilitated a shift toward linearity in pay. This greater substitutability and pay linearity have helped close the within-occupation wage gap.

Pharmacists are paid an almost equal hourly wage—there is no wage premium for working traditional office hours and there is not a large wage penalty for part-time work. This helps to decrease the wage gap between men, who are more likely to be full-time workers, and women, who are more likely to work part time.21Goldin and Katz, “Most Egalitarian Profession.”

Given these insights regarding the remaining disparities in earnings between men and women, as well as the insights regarding what features of an occupation may drive more equal pay, it appears that occupational licensing could have the potential to contribute to alleviating gender pay differences if it increases substitutability between workers and produces linearity in pay similar to what is seen in the pharmacy profession. In other words, occupational licensing may reduce the wage gap if licenses and related credentials make individual workers more substitutable. Licensing laws do likely make some workers more substitutable, since they establish a minimal requirement for work experience and education and offer some level of quality control. If the resulting greater substitutability increases temporal flexibility and linearity in pay, occupational licensing may accordingly reduce the wage gap.

Additionally, occupational licensing laws could increase pay transparency if trade organizations report average pay for workers. To the extent that this information is accurate and readily available, it could also potentially narrow the wage gap. Recent literature suggests that increased pay transparency narrows the gender wage gap by slowing down the growth of male wages22Morten Bennedsen et al., “Do Firms Respond to Gender Pay Gap Transparency?” (NBER Working Paper No. 25435, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, January 2019). and increasing wages for women with higher education levels.23Marlene Kim, “Pay Secrecy and the Gender Wage Gap in the United States,” Industrial Relations 54, no. 4: 648–67.

Occupational licensing could increase the wage gap, on the other hand, by imposing geographic constraints on mobility, limiting job switching, increasing the costs of labor force absences, and encouraging nonentry into the licensed field.

If occupational licensure acts as a geographic constraint and limits worker mobility, the gender wage gap could increase. Research has shown that individuals who work in occupations that require state-specific licensing exams are much less likely to move across state lines than individuals in nonlicensed professions.24Janna E. Johnson and Morris M. Kleiner, “Is Occupational Licensing a Barrier to Interstate Migration?,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 12(3):347-73. The license makes it more costly to move. Since women often increase their wages by changing employers, this limits their possibilities.

Geographic constraints are particularly important for employees trailing their spouses. Women are historically more likely to be trailing spouses, and the existing literature seems to suggest that they continue to be more likely than men to be the spouse who moves for a partner’s job.25Summarizing the existing literature on the topic of tied migration and labor force participation and employment, a 2009 study suggests that women are more likely than men to be tied migrants. Thomas J. Cooke et al., “A Longitudinal Analysis of Family Migration and the Gender Gap in Earnings in the United States and Great Britain,” Demography 46, no. 1 (2009): 147–67. While good empirical evidence on the absolute number of trailing spouses by gender is nonexistent, William Bielby and Denise Bielby report that women are more likely than men to report reluctance to relocate for a better job (for themselves).26William T. Bielby and Denise D. Bielby, “I Will Follow Him: Family Ties, Gender-Role Beliefs, and Reluctance to Relocate for a Better Job,” American Journal of Sociology 97, no. 5 (1992): 1241–67. If a couple moves as a result of the trailed spouse’s employment prospects and the move requires the trailing spouse to obtain a license or other credential in order to continue working in the same occupation, the credential can become a barrier to entry that results in the trailing spouse taking a lower-paying position or staying out of the labor force altogether.

Though it does not specifically examine the impact of licensure laws, research examining the effects of job relocation on spousal careers suggests that family relocation negatively affects women’s earnings both in absolute terms and relative to their husbands’ earnings, which increase.27Cooke et al., “Longitudinal Analysis of Family Migration.” Additional contributions, which corroborate the findings of Cooke and his coauthors, include the following: Thomas J. Cooke, “Family Migration and the Relative Earnings of Husbands and Wives,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 93 (2003): 338–49; Joyce P. Jacobsen and Laurence M. Levin, “Marriage and Migration: Com- paring Gains and Losses from Migration for Couples and Singles,” Social Science Quarterly 78, no. 3 (1997): 688–709; Felicia B. LeClere and Diana K. McLaughlin, “Family Migration and Changes in Women’s Earnings: A Decomposition Analysis,” Population Research and Policy Review 16 (1997): 315–35; Kimberlee A. Shauman and Mary C. Noonan, “Family Migration and Labor Force Outcomes: Sex Differences in Occupational Context,” Social Forces 85, no. 4 (2007): 1735–64. Jeremy Burke and Amalia Miller look at evidence from military families and find that spousal earnings decline by 14 percent after a move, that a move increases the likelihood of no earnings for the spouse, and that these career costs persist for two years after the move.28Jeremy Burke and Amalia R. Miller, “The Effects of Job Relocation on Spousal Careers: Evidence from Military Change of Station Moves,” Economic Inquiry 56, no. 2 (2018): 1261–77. The authors specifically note both that spouses may avoid entering fields that require a license because of the barrier to entry licenses create and that wages may be negatively affected for spouses in licensed fields. The military has noted the impacts of licensure on spousal careers by offering the Spouse Education and Career Opportunities Call Center for career and education counseling around licensure, and the Defense-State Liaison Office has recently worked to change state laws to better accommodate state reciprocity in licensure for military spouses. These actions suggest that female earnings are negatively impacted by some state licensing. The continuing education requirements for many state-licensed occupations also have the potential to adversely impact women at higher rates than men. Women are more likely to take a break from their careers owing to concerns about childcare or elderly parents and to choose to work part time.29A 2013 Pew Research Center study reports that 42% of mothers and 28% of fathers said they had to reduce work hours in order to care for a child or a family member. In the same study, 39% of mothers and 24% of fathers said they had taken a significant amount of time off in order to care for a child or a family member, and 27% of mothers and 10% of fathers said they had quit a job in order to care for a child or family member. Pew Research Center, On Pay Gap, Millennial Women Near Parity—for Now (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2013). In 2011, mothers spent, on average, 14 hours per week caring for children, while fathers spent only 7 hours. For more information regarding the differences between mothers and fathers in terms of the amount of time spent on childcare and housework, see Pew Research Center, Modern Parenthood (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2013). These decisions can make required continuing education credits prohibitively expensive for women to acquire, in terms of both time and money. Often larger employers will help employees meet continuing education requirements by hosting classes or by helping to offset the monetary outlay required for attending classes. Workers who take a break from their profession can find it difficult to gather information about continuing education requirements. Additionally, the opportunity cost of continuing education likely changes during a career break: Someone who is not currently employed in the licensed profession can’t use work hours to meet continuing education requirements, but must instead take time that was allocated to child- care or elderly care, to other careers or schooling, or to dealing with health concerns. Finally, the relative costs of any testing and classes, in monetary terms and in terms of time spent, are significantly higher for a part-time worker (and earner) than for an individual currently working and earning a full-time salary in a licensed profession spending a similar amount of money and time.

For example, when Massachusetts adopted a continuing education requirement for licensed real estate agents in 1999, the number of licensed active agents decreased by between 39 and 58 percent.30Benjamin Powell and Evgeny Vorotnikov, “Real Estate Continuing Education: Rent Seeking or Improvement in Service Quality?,” Eastern Economic Journal 38, no. 1 (2012): 57–73. The National Association of Realtors notes that the majority of realtors are women—meaning this regulatory change likely adversely affected women at higher rates than men.

An occupational license is now required in a large number and variety of fields. It is possible that a license decreases the wage gap in some fields, exacerbates it in others, and has dual effects (working in both directions) in still others. Occupational licensure likely also changes who enters the licensed field, further complicating attempts to understand licensure’s impact on gender wage gaps. While empirical research can help bring better understanding of licensure’s impacts, the complexity of the ways that licensing could impact wages complicates these studies.

Occupational Licensing and Race

As in the case of the gender wage gap, occupational licensing has the potential to decrease the racial wage gap if licensure increases substitutability for all workers along the lines suggested by Goldin and Katz and if it reduces the information asymmetry between employees and employers relating to employees’ qualifications. Asymmetric information regarding employee qualification is particularly problematic for minority workers. Employee quality is difficult to observe ex ante—consequently, in the absence of sufficient information, employers may rely on observable characteristics such as race and gender to infer worker ability and productivity. As a result, individual applicants may be judged not solely on the basis of observable individual characteristics but also on the basis of the average characteristics of a group they are observed to belong to. If employers are legally prohibited from asking questions about criminal background, they may infer information about an individual’s criminal background from the individual’s race or gender. Women are less likely to have a criminal record than men, and white individuals are less likely to have a criminal record than black or Latino individuals, on average.31David Neumark, “Wage Differentials by Race and Sex: The Roles of Tastes Discrimination and Labor Market Information,” Industrial Relations 38, no. 3 (1999): 414-445. This kind of statistical discrimination is difficult for individual workers to overcome.

Amanda Agan and Sonja Starr provide some evidence for the presence of this kind of statistical discrimination. They show that black applicants were significantly less likely to receive resume callbacks and were less likely to be employed in “ban the box” states in which employers are prohibited from including questions relating to criminal background on job applications.32Amanda Agan and Sonja Starr, “Ban the Box, Criminal Records, and Racial Discrimination: A Field Experiment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 133, no. 1 (2018): 191–235. In an environment in which other job-market signals are unavailable, licenses can potentially help minorities overcome such asymmetric information problems with respect to worker productivity and qualification. While employers may not be able to ask questions about criminal background directly, they can require a license or certification—which often includes a criminal back- ground check as a prerequisite. Having to show a license can therefore allow minority workers to signal qualifications beyond the average of the minority group they belong to and avoid statistical discrimination. In other words, if licenses provide consistent signals about worker qualities that are otherwise difficult to communicate, especially for minorities, they may reduce wage inequality.

Occupational licensing could, however, also aggravate the wage gap between workers of different races if the positive effect of increased substitutability is outweighed by negative effects of increasing and differentiating barriers to entry for different races. For example, occupational licensure laws are widely accepted to reduce the labor supply in the market—the credentialing aspect of the license means there are fewer suppliers of labor in that market. If this decrease in supply is felt more heavily by minority groups, the wage gap could increase.

The presence of licensing requirements might alter worker selection into a field. Individuals who are deterred from entering a profession because of licensing requirements would not show up in a wage gap study since they would not be considered to be in the field. It is possible that a license requirement would deter larger numbers of minority workers from entering a labor market than white workers. For example, occupational licensure laws often impose significant educational requirements workers must fulfill in order to obtain and maintain the license. If minorities graduate from trade schools and colleges at lower rates than their white counterparts, they will be ineligible for many licensed jobs at higher rates than white individuals.33A 2017 study by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center examined educational outcomes by race and ethnicity and found, approximately, that Hispanic students completed a degree or certificate program within six years at a rate of 46 percent and black students completed such a program within six years at a rate of 38 percent, while white students completed it within six years at a rate of 62 percent. Doug Shapiro et al., “Completing College: A National View of Student Attainment Rates by Race and Ethnicity—Fall 2010 Cohort” (Signature Report No. 12b, National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, Herndon, VA, April 2017). Licensure rules that prohibit individuals with recorded felonies from entering the licensed professions could impact minorities at higher rates than white individuals.34Sarah K. S. Shannon et al., “The Growth, Scope, and Spatial Distribution of People with Felony Records in the United States, 1948–2010,” Demography 54 (2017): 1795–818. Similarly, a lack of access to credit35For example, a report issued by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland based on the 2016 Small Business Credit Survey suggests that black-owned firms have difficulty obtaining credit for business expansions. For more information on these challenges, see Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, 2016 Small Business Credit Survey Report on Minority-Owned Firms, November 2017. to pay for exam and application fees could prevent minorities from entering a field at higher rates than white workers. In all these cases, the licensing requirement does not benefit minority workers unless they can meet the requirements of licensure. Statistics relating to within-occupation earnings for minority workers are therefore potentially skewed if minority workers are less likely to enter a profession in the first place.

Empirical Results

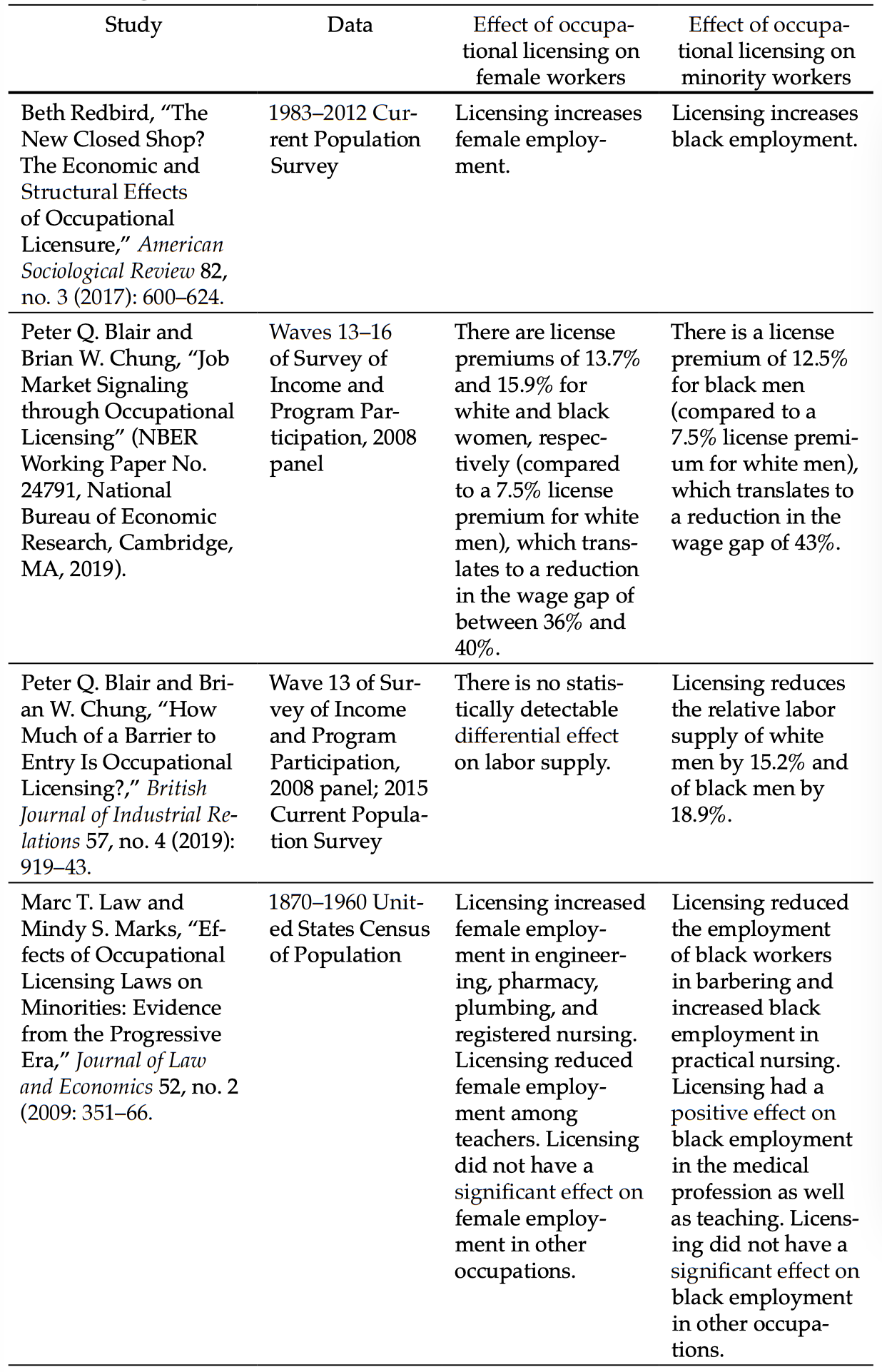

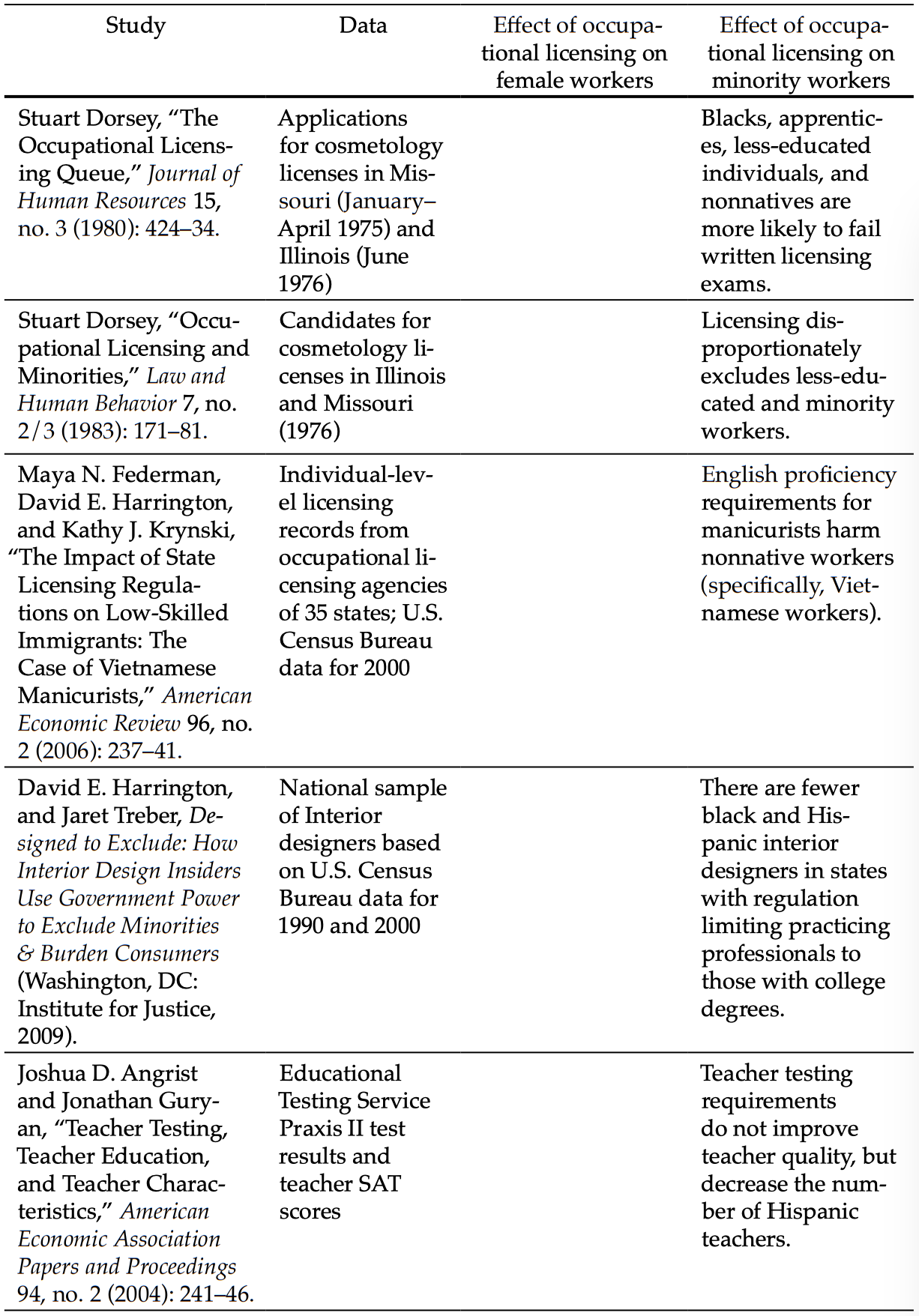

The empirical evidence on how occupational licensing affects female or minority labor-market outcomes is mixed. Recent contributions suggest that occupational licensing reduces both the gender wage gap and the racial wage gap, and that it does not effectively function as a barrier to entry with divergent effects on minorities and white workers. As noted earlier, however, there is concern that worker selection skews these results. Older research suggests that occupational licensing and regulation more generally benefited white men at the expense of women and minorities. For example, a 2010 paper finds that stricter regulations for funeral directors reduce the proportion of women in that profession by 24 percent.36Alison Cathles, David E. Harrington, and Kathy Krynski, “The Gender Gap in Funeral Directors: Burying Women with Ready-to-Embalm Laws?,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48, no. 4 (2010): 688–705. This chapter’s appendix summarizes the main results of a number of empirical contributions to this literature. However, some recent empirical evidence suggests that occupational licensing increases wages within a profession, may reduce the gender and racial wage gap, and may increase the employment of women and minorities. Peter Blair and Brian Chung find that occupational licensing narrows the gender wage gap by 36–40 percent (36% for white women and 40% for black women, as compared to white men). More specifically, using data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation, they report that the license premium for white and black women was

13.7 percent and 15.9 percent, as compared to 7.5percent for white men. They also find that occupational licensing narrows the gender wage gap by 36-40% and the wage gap between black and white men by 43 percent.37Peter Q. Blair and Brian W. Chung, “Job Market Signaling through Occupational Licensing” (NBER Working Paper No. 24791, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2019). Beth Redbird finds that occupational licensing does not increase wages, but that it improves access to licensed occupations for historically disadvantaged groups, including black and female workers.38Beth Redbird, “The New Closed Shop? The Economic and Structural Effects of Occupational Licensure,” American Sociological Review 82, no. 3 (2017): 600–624. Note that Deyo, Kleiner, and Timmons question the validity of Redbird’s findings. They specifically criticize Redbird’s lack of a theoretical framework, the data she uses, and her empirical methodology. Darwin Deyo, Edward Timmons, and Morris Kleiner, “A Response to ‘New Closed Shop: The Economic and Structural Effects of Occupational Licensure’,” Mercatus Policy Brief, November 2018. Redbird hypothesizes that the increased share of minorities among licensed professionals is the result of formal procedures, such as licenses, replacing informal barriers to entry. She suggests that formal barriers to entry are more likely to be color-blind and measurable and can be publicized, while informal barriers to entry into a profession may encourage discrimination and homogeneity.

Blair and Chung find that black men in particular benefit from licenses that signal nonfelony status: in their sample, black men in a licensed profession on average earned a premium of 12.5 percent, as compared to a 7.5 percent premium for licensed white men. Blair and Chung argue that licenses serve as a job-market signal that allows minority workers to overcome asymmetric information between firms and workers, who are subject to statistical discrimination relating to employee productivity and to quality more generally.39Blair and Chung, “Job Market Signaling.” More specifically, licenses help to overcome barriers to entry for African American men for whom employers overestimate the likelihood of a criminal past.40Agan and Starr, “Ban the Box.”

One major concern regarding occupational licensing is that it will reduce the supply of labor in licensed professions41Kleiner and Soltas, “Welfare Analysis of Occupational Licensing.” and will change the characteristics of those entering those professions. For example, a higher education requirement might encourage some women to not enter an occupation, or a nonfelony status requirement might exclude some minority workers who would otherwise have pursued a certain career. Evidence reported by Ryan Nunn supports the idea that licensing might skew access.42Ryan Nunn, “How Occupational Licensing Matters for Wages and Careers,” Brookings Institution, March 2018 and Ryan Nunn, “Occupational Licensing and American Workers,” Economic Analysis – The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, June 2016. Nunn reports that 27 percent of non-Hispanic whites hold occupational licenses while only 22 percent of blacks and 15 percent of Hispanics hold licenses. The exclusion of these workers will not show up readily in an empirical analysis, but it certainly impacts the wages that people will or will not earn.

Blair and Chung may temper Nunn’s results, however. They suggest that occupational licensing reduces labor supply by an average of 17–27 percent. But their results also suggest that the negative effects of licensing are stronger for white workers and weaker for black workers.43Peter Q. Blair and Brian W. Chung, “How Much of a Barrier to Entry Is Occupational Licensing?,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57, no. 4 (2019): 919–43. This reduction in the wage and employment gap cannot be a desirable result if it comes at the expense of absolute minority employment, however. The fact that a profession has relatively more minority employment or a smaller wage gap between white and black workers is only a desirable outcome if these changes are the result of minority workers being absolutely better off.

Shedding light on this concern, Morris Kleiner shows that licensed occupations grow at a rate that is 20 percent less than that of unlicensed occupations,44Morris M. Kleiner, “A License for Protection,” Regulation 29, no. 3 (Fall 2006): 17–21. which suggests that, rather than improving opportunities for minorities, licensing may just reduce opportunities for employment overall. This evidence suggests that when the wage gap within a field decreases, this may not mean workers are doing better overall. In fact, some of the relative improvements among minorities may be the result of reductions in the wages and employment of white men rather than the result of increases in the wages or employment of black men. These mixed empirical results suggest that more research needs to be done to better understand the effects of licensure on market outcomes. It’s possible that licensure laws help female and minority labor market outcomes in some circumstances and hurt them in others. Research needs to more closely examine the impact of licensure on worker selection, socioeconomic status, part-time work, style of work, and education in order to more clearly differentiate these effects.

Other Types of Regulation, Gender, and Race

A handful of studies consider the effect of specific regulatory reforms on minorities. A 1994 study finds that deregulation of trucking resulted in a dramatic increase in the proportion of black drivers, who had previously been prohibited from entering the industry by the predominantly white trucking business owners who were the beneficiaries of trucking regulation.45John S. Heywood and James H. Peoples, “Deregulation and the Prevalence of Black Truck Drivers,” Journal of Law and Economics 37, no. 1 (1994): 133–55. Sandra Black and Philip Strahan consider the differential effect of banking deregulation on male and female workers in the industry. They find that, while deregulation reduced earnings for all workers in banking, women were relative beneficiaries of the reforms, which reduced the gender wage gap in the banking industry. In addition, women’s share of employment in managerial positions increased following deregulation.46Sandra E. Black and Philip E. Strahan, “The Division of Spoils: Rent-Sharing and Discrimination in a Regulated Industry,” American Economic Review 91, no. 4 (2001): 814–31. A 2019 study finds that the cost of regulation in terms of wage effects is mostly borne by lower-wage workers and that workers in higher-earning managerial and compliance-relevant professions, such as accountants and lawyers, earn higher wages when an industry becomes more regulated.47Bailey, Thomas, and Anderson, “Regressive Effects of Regulation on Wages.” These studies help highlight how the barrier-to-entry aspect of regulation may be more costly to women and minority workers than to white male workers.

While some of the effects discussed above may be small and may be considered negligible or justifiable costs by advocates of greater levels of regulation, an important downside of regulation, especially when it is ineffective in terms of achieving its desired goal, is that it creates a group with a vested interest in its persistence. Regulation that redistributes resources from one group to another but is otherwise ineffective will have advocates in those who benefit from the law, and thus will be more persistent than its relative policy success might suggest. Gordon Tullock coined the term “transitional gains trap” to describe this phenomenon of regulatory persistence in the face of policy failure.48Gordon Tullock, “The Transitional Gains Trap,” Bell Journal of Economics 6, no. 2 (1975): 671–78.

Policy Reform

Even when it is well-intentioned, labor-market regulation such as occupational licensing laws can have unforeseen yet detrimental effects that are particularly burdensome for minorities and women. As we have shown above, the empirical record about occupational licensing laws is by no means easy to assess or clear cut. While such laws seem to increase wages for those in the licensed profession, they do so at the expense of reductions in employment both in the short term and dynamically in the long term. Several of the studies we reviewed earlier suggest that such employment effects are most severe for women and minorities, although there is recent evidence that suggests that the share of women and minorities in certain professions increases with licensure.

Overall, occupational licensing laws are similar to regulation more generally in that they redistribute earnings and employment among groups. While the specific redistributive effects of occupational licensing laws are difficult to trace, existing evidence suggests that incumbent workers in an industry benefit at the expense of newcomers, including women and minorities. Occupational licensing also changes who is able and willing to enter a field. Evidence also suggests that occupations with licensing laws are less dynamic—that is, less likely to grow. This is troubling if one policy goal is wage growth for women and minority groups. Wages grow the most in dynamic industries. This evidence is in line with an emerging literature on the regressive effects of regulation, which identifies detrimental effects for low-income households as an important cost of regulatory accumulation.49See several contributions to a special issue of Public Choice on the topic, most importantly Michael D. Thomas, “Reapplying Behavioral Symmetry: Public Choice and Choice Architecture,” Public Choice 180, no. 1/2 (2019): 11–25; Chambers, Collins, and Krause, “How Do Federal Regulations Affect Consumer Prices?”; Bailey, Thomas, and Anderson, “Regressive Effects of Regulation on Wages”; G. P. Manish and Colin O’Reilly, “Banking Regulation, Regulatory Capture, and Inequality,” Public Choice 180, no. 1/2 (2019): 145–64. For a discussion of regulation more generally, see Bentley Coffey, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Pietro Peretto, “The Cumulative Cost of Regulations,” Review of Economic Dynamics, forthcoming.

In light of this evidence on occupational licensing and on regulation more generally, additional licensing laws should be considered with great caution. Empirical research on occupational licensure is mixed, researchers regularly question the data used in studies, and the necessity of many licensure laws for health and safety has also begun to be questioned.50David Skarbek, “Occupational Licensing and Asymmetric Information: Post-hurricane Evidence from Florida,” Cato Journal 28, no. 1 (2008): 71–80. With more than 25 percent of the workforce already required to hold a license to perform their jobs, policymakers should be cautious about expanding this practice to include even more professions and workers.

Given high existing levels of occupational licensing in the states, a move toward greater labor market freedom and general deregulation may be more effective for generating economic growth. Economic growth will, in turn, increase wage growth for women and minorities. Most occupational licensure happens through state legislation. This makes blanket policy recommendations difficult to deliver. We caution all policymakers against enacting additional licensure laws without careful study of their impacts. We also suggest that existing licensure laws be carefully examined to see whether they are necessary for the health and safety of consumers. Such studies should also consider secondary effects of regulation.

In the process of considering new regulation or examining existing laws, policymakers should consider whether a voluntary certification program could provide similar benefits to consumers. Voluntary certification has the potential to provide many of the possible benefits of licensure discussed earlier (especially the benefits related to overcoming asymmetric information problems and avoiding statis- tical discrimination) without excluding from the labor market large segments of workers who cannot meet the educational, monetary, or time burden involved in obtaining a certificate. On net, voluntary certification would be more dynamic than licensure and would provide customers with more choice.

Conclusion

As described in this chapter, the evidence is largely inconclusive regarding the differential effect of regulation on women and minorities and, more specifically, the differential effect of occupational licensing laws on those groups. While some recent research seems to find that licensing laws have a positive effect on gender and minority wage gaps, the difficulty with the existing evidence is that it cannot control for potential effects of such laws on differential access to labor markets. If occupational licensing laws disproportionately disincentivize labor market participation by women and minorities, the narrowing of gender and minority earnings gaps comes at the high cost of dis-employment for such groups.

On the whole, licensure is likely an expensive way to help minorities and women, because it hurts consumers and potential entrants to licensed professions and increases unemployment, while not necessarily (or only imperfectly) creating the circumstances that promote wage equality.

Appendix: Table of Empirical Studies on Occupational Licensing and Gender or Race

References

Agan, Amanda and Sonja Starr. “Ban the Box, Criminal Records, and Racial Discrimination: A Field Experiment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 133. No. 1 (2018): 191–235.

Bailey, James and Diana Thomas. “Regulating Away Competition: the effect of regulation on entrepreneurship and employment.” Journal of Regulatory Economics. 52 (2017): 237-254.

Bailey, James, Diana W. Thomas, and Joseph Anderson. “Regressive Effects of Regulation on Wages.” Public Choice 180. No. 1/2 (2019): 91–103.

Becker, Gary S. The Economics of Discrimination (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957).

Bennedsen, Morten et al. “Do Firms Respond to Gender Pay Gap Transparency?” (NBER Working Paper No. 25435. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. January 2019).

Bielby, William T. and Denise D. Bielby. “I Will Follow Him: Family Ties, Gender-Role Beliefs, and Reluctance to Relocate for a Better Job.” American Journal of Sociology 97. No. 5 (1992): 1241–67.

Black, Sandra E. and Philip E. Strahan. “The Division of Spoils: Rent-Sharing and Discrimination in a Regulated Industry.” American Economic Review 91. No. 4 (2001): 814–31.

Blair, Peter Q. and Brian W. Chung. “How Much of a Barrier to Entry Is Occupational Licensing?” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57. No. 4 (2019): 919–43.

Blair, Peter Q. and Brian W. Chung. “Job Market Signaling through Occupational Licensing” (NBER Working Paper No. 24791. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. 2019).

Blau, Francis D. and Lawrence M. Kahn. “Gender Differences in Pay.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14. No. 4 (2000): 70.

Blau, Francis D. and Lawrence M. Kahn. “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations.” Journal of Economic Literature 55. No. 3 (2017): 789–865.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2018.” BLS Report 1083. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-earnings/2018/pdf/home.pdf.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.” Last modified January 22, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat49.htm.

Burke, Jeremy and Amalia R. Miller. “The Effects of Job Relocation on Spousal Careers: Evidence from Military Change of Station Moves.” Economic Inquiry 56. No. 2 (2018): 1261–77.

Cathles, Alison, David E. Harrington, and Kathy Krynski. “The Gender Gap in Funeral Directors: Burying Women with Ready-to-Embalm Laws?” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48. No. 4 (2010): 688–705.

Chambers, Dustin, Courtney A. Collins, and Allan Krause. “How Do Federal Regulations Affect Consumer Prices? An Analysis of the Regressive Effects of Regulation.” Public Choice 180. No. 1/2 (2019): 57–90.

Chambers, Dustin, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Laura Stanley. “Barrier to Prosperity: The Harmful Impact of Entry Regulations on Income Inequality.” Public Choice 180. No. 1/2 (2019): 165–90.

Chambers, Dustin, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Laura Stanley. “Barrier to Prosperity: The Harmful Impact of Entry Regulations on Income Inequality.” Public Choice 180. No. 1/2 (2019): 165–90.

Coffey, Bentley, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Pietro Peretto. “The Cumulative Cost of Regulations.” Review of Economic Dynamics, forthcoming.

Cooke, Thomas J. “Family Migration and the Relative Earnings of Husbands and Wives.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 93 (2003): 338–49.

Cooke, Thomas J. et al. “A Longitudinal Analysis of Family Migration and the Gender Gap in Earnings in the United States and Great Britain.” Demography 46. No. 1 (2009): 147–67.

Deyo, Darwin, Edward Timmons, and Morris Kleiner. “A Response to ‘New Closed Shop: The Economic and Structural Effects of Occupational Licensure’.” Mercatus Policy Brief. November 2018.

Djankov et. al. (2002), Klapper, Laeven, Rajan (2006) Simeon Djankov, Raphael La Porta, Florenzio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. (2002). “The Regulation of Entry.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (2002). No. 1: 1-37.

Djankov, Simeon, Caralee McLiesh, and Rita Ramalho. “Regulation and Growth.” Economics Letters. 92 (2006): 395-401.

Ekelund, Robert B. and Robert D. Tollison. “The Interest-Group Theory of Government.” The Elgar Companion to Public Choice, ed. William F. Shughart II and Laura Razzolini (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2001).

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. 2016. Small Business Credit Survey Report on Minority-Owned Firms. November 2017.

Friedman, Milton. Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1962).

Gittleman, Maury, Mark A. Klee, and Moriss M. Kleiner. “Analyzing the Labor Market Outcomes of Occupational Licensing.” Industrial Relations 57. No. 1 (2018): 57–100.

Goldin, Claudia and Lawrence F. Katz. “A Most Egalitarian Profession: Pharmacy and the Evolution of a Family-Friendly Occupation.” Journal of Labor Economics 34. No. 3 (July 2016): 705–46.

Goldin, Claudia. “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter.” American Economic Review 104. No. 4 (2014): 1091–119.

Heywood, John S. and James H. Peoples, “Deregulation and the Prevalence of Black Truck Drivers.” Journal of Law and Economics 37. No. 1 (1994): 133–55.

Jacobsen, Joyce P. and Laurence M. Levin. “Marriage and Migration: Comparing Gains and Losses from Migration for Couples and Singles.” Social Science Quarterly 78. No. 3 (1997): 688–709.

Johnson, Janna E. and Morris M. Kleiner. “Is Occupational Licensing a Barrier to Interstate Migration?” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 12(3):347-73.

Kim, Marlene. “Pay Secrecy and the Gender Wage Gap in the United States.” Industrial Relations 54. No. 4: 648–67.

Klapper, Leora, Luc Laeven, and Raghuram Rajan. “Entry regulation as a barrier to Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Financial Economics. 82 (2006). No:3: 591-629.

Kleiner, Morris M. “A License for Protection.” Regulation 29. No. 3 (Fall 2006): 17–21.

Kleiner, Morris M. and Evan J. Soltas. “A Welfare Analysis of Occupational Licensing in U.S. States” (NBER Working Paper No. 26383. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA. October 2019).

LeClere, Felicia B. and Diana K. McLaughlin. “Family Migration and Changes in Women’s Earnings: A Decomposition Analysis.” Population Research and Policy Review 16 (1997): 315–35.

Manish, G. P. and Colin O’Reilly. “Banking Regulation, Regulatory Capture, and Inequality.” Public Choice 180. No. 1/2 (2019): 145–64.

Neumark, David. “Wage Differentials by Race and Sex: The Roles of Tastes Discrimination and Labor Market Information.” Industrial Relations 38. No. 3 (1999): 414-445.

Nunn, Ryan. “How Occupational Licensing Matters for Wages and Careers.” Brookings Institution. March 2018.

Nunn, Ryan. “Occupational Licensing and American Workers.” Economic Analysis – The Hamilton Project. Brookings Institution. June 2016.

Nunn, Ryan. Occupational Licensing and American Workers (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. 2016).

Pew Research Center. Modern Parenthood (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. 2013).

Pew Research Center. On Pay Gap, Millennial Women Near Parity—for Now (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. 2013.

Powell, Benjamin and Evgeny Vorotnikov. “Real Estate Continuing Education: Rent Seeking or Improvement in Service Quality?” Eastern Economic Journal 38. No. 1 (2012): 57–73.

Redbird, Beth. “The New Closed Shop? The Economic and Structural Effects of Occupational Licensure.” American Sociological Review 82. No. 3 (2017): 600–624.

Shannon, Sarah K. S. et al. “The Growth, Scope, and Spatial Distribution of People with Felony Records in the United States. 1948–2010.” Demography 54 (2017): 1795–818.

Shapiro, Doug et al. “Completing College: A National View of Student Attainment Rates by Race and Ethnicity—Fall 2010 Cohort” (Signature Report No. 12b. National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Herndon, VA. April 2017).

Shauman, Kimberlee A. and Mary C. Noonan. “Family Migration and Labor Force Outcomes: Sex Differences in Occupational Context.” Social Forces 85. No. 4 (2007): 1735–64.

Skarbek, David. “Occupational Licensing and Asymmetric Information: Post-hurricane Evidence from Florida.” Cato Journal 28. No. 1 (2008): 71–80.

Thomas, Diana W. “Regressive Effects of Regulation.” Public Choice 180. No. 1/2 (2019): 1–10.

Thomas, Michael D. “Reapplying Behavioral Symmetry: Public Choice and Choice Architecture.” Public Choice 180. No. 1/2 (2019): 11–25.

Tullock, Gordon. “The Transitional Gains Trap.” Bell Journal of Economics 6. No. 2 (1975): 671–78.

Table of Contents

- Regulation and Entrepreneurship: Theory, Impacts, and Implications

- Regulation and the Perpetuation of Poverty in the US and Senegal

- Social Trust and Regulation: A Time-Series Analysis of the United States

- Regulation and the Shadow Economy

- An Introduction to the Effect of Regulation on Employment and Wages

- Occupational Licensing: A Barrier to Opportunity and Prosperity

- Gender, Race, and Earnings: The Divergent Effect of Occupational Licensing on the Distribution of Earnings and on Access to the Economy

- How Can Certificate-of-Need Laws Be Reformed to Improve Access to Healthcare?

- Land Use Regulation and Housing Affordability

- Building Energy Codes: A Case Study in Regulation and Cost-Benefit Analysis

- The Tradeoffs between Energy Efficiency, Consumer Preferences, and Economic Growth

- Cooperation or Conflict: Two Approaches to Conservation

- Retail Electric Competition and Natural Monopoly: The Shocking Truth

- Governance for Networks: Regulation by Networks in Electric Power Markets in Texas

- Net Neutrality: Internet Regulation and the Plans to Bring It Back

- Unintended Consequences of Regulating Private School Choice Programs: A Review of the Evidence

- “Blue Laws” and Other Cases of Bootlegger/Baptist Influence in Beer Regulation

- Smoke or Vapor? Regulation of Tobacco and Vaping

- Moving Forward: A Guide for Regulatory Policy