As summer ends, you can learn an important lesson about immigration policy from your final trip to the beach.

Scoop up a handful of sand. Hold it loosely with your palm open. Then close your hand and squeeze as tight as you can. The sand slips through your fingers.

Just as squeezing the sand leaves you with less in your hand, many of our tighter enforcement efforts have left the United States with less control over our borders. Decades of research indicate that the best immigration policies aren’t heavy enforcement. Openhanded approaches that provide various options for immigrants and US employers have provided long-term benefits to the economy.

This is why policymakers should think twice about statements like “There’ll be no immigration reform until you get control of the border.” The impulse is correct. Everyone agrees that we should protect the country against dangerous people. However, it forbids our most promising tool for fixing the border: immigration reform that creates legal pathways for working in the United States.

Rather than viewing immigration reform as off the table until the border is under control, Congress can bring order to the border by clearing existing paths to legal status and creating new avenues for legal immigration. Research from past episodes of bipartisan reform shows that there is much to be gained and little to lose.

Creating a legal pathway enables economic growth

Policy wonks on the right and left agree that creating legal pathways or expanding guest worker programs provides economic benefit to the country. For example, several reports—from think tanks on both sides of the political spectrum—look at the effects of ending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy.

DACA applies to people brought to the country as children without authorization. It allows them to remain in the country, work under certain conditions, and has around 600,000 participants.

Researchers at the American Action Forum, a business-oriented and right-leaning think tank, pointed out that DACA recipients contribute about $3.4 billion in taxes to the federal government each year and almost $42 billion to annual US GDP. They also point out that deportation isn’t a free lunch—removing Dreamers will cost between $7 billion and $21 billion.

At the Cato Institute, researchers Logan Albright, Ike Brannon, and M. Kevin McGee estimated the effects of ending DACA on the US economy from 2019 to 2028. They conclude that such a change would cost the economy $351 billion and the US Treasury would lose out on $92.9 billion in tax revenue—nearly $10 billion a year.

Cato’s estimates look a lot like the results from four tax experts at the left-leaning Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). In the ITEP’s report, the authors analyze the tax contributions of undocumented immigrants and conclude that they contribute around $11.74 billion in state and local taxes. Two of the ITEP’s authors conclude that DACA holders contribute about $1.7 billion a year in a separate analysis.

The agreement from both sides on the benefits of immigration extends beyond the policy world in Washington and into the academic world. A recent report by the Latino Policy and Politics Initiative (LPPI) at UCLA projected the economic effects of four different policies that would give some form of permanent legal status to different groups of immigrants. Importantly, this report analyzed the effects of creating legal pathways for permanent status to both undocumented immigrants and legal immigrants who currently can’t become legal permanent residents. For example, those holding Temporary Protected Status (TPS), which is granted because of war, disease, or natural disaster. This is despite the long periods of time that TPS holders are often in the country. In the case of El Salvador, Haiti, and Honduras, often for 20 years or more.

The analysis by researchers at LPPI shows that creating any kind of permanent legal status for those who currently can’t do so would benefit the US economy. On the high end, they estimate between $1.5 trillion added to GDP and around 371,000 new jobs created over the next 10 years. On the lower end, they expect around $62 billion added to the GDP and 15,000 jobs for very small new legal immigration programs.

That multiple studies from groups of all political persuasions find economic benefits from expanding legal pathways isn’t surprising. It’s a common conclusion in research on immigration. CGO contributing scholar and macroeconomist James Feigenbaum estimates that a pathway to legal status is always a better deal than deportation.

Past amnesties did not encourage more illegal immigration

This research clearly shows the economic gains of simplifying the pathway to legal permanent residency, but what about the long-term consequences to immigration? Does giving legal status to undocumented immigrants increase illegal immigration by rewarding it?

Immigration experts Pia M. Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny examined the effects of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). IRCA, the 1986 amnesty law signed by President Reagan, gave 2.7 million undocumented immigrants a way to become legal residents. The short-term consequence: apprehensions at the border dropped. Long-term, the bill had no effect on rates of undocumented immigration.

Orrenius and Zavodny conclude that, “it appears that amnesty programs do not encourage undocumented immigration, as some critics of amnesty programs have charged.” Creating a legal pathway is unlikely to cause a large increase in immigration flows in order to take advantage of immigration reforms.

What we can learn from amnesty’s record

On the one hand, Reagan’s IRCA didn’t increase undocumented immigration. Yet on the other, it also failed to reduce it. At first, this may seem a frustrating finding for those interested in getting control of US borders and immigration. But the reality is not disempowering. Policymakers can learn a lot from this one-off legalization pathway.

IRCA’s failure to reduce long-term illegal immigration suggests that the policy may have been too short-lived. A promising insight comes from early research by Cato’s group of immigration scholars on the relationship between guest worker visa programs and illegal border crossings. By analyzing an 18-year period, they show a relationship between increasing temporary work visas and falling apprehensions of Mexicans illegally crossing the southern border.

As Cato’s David Bier concludes, from 2000 to 2018, a “1 percent increase in H-2 visas for Mexicans…was associated with a 1 percent decline in the absolute number of Mexicans apprehended for crossing illegally.” Expanding legal pathways reduces illegal immigration.

Escalating border enforcement hasn’t stopped illegal immigration

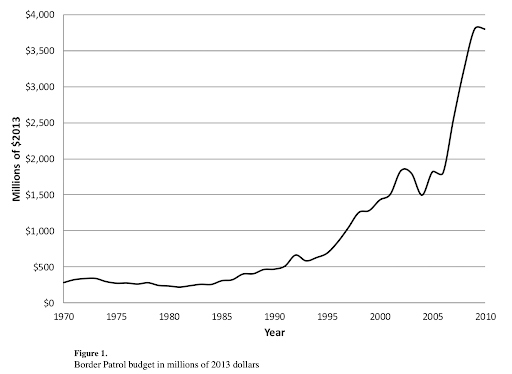

Stepping up border enforcement alone can increase illegal immigration because it forces workers to change their seasonal visits to permanent settlements. In a famous 2016 study, three immigration researchers showed that the increase in border enforcement has backfired by making it difficult for workers to move back and forth across the border. The once-temporary farm workers became permanent residents. Notably, the researchers found that increasing the Border Patrol’s budget from less than $500 million in 1970 to more than $3.5 billion in 2010 also failed to reduce the number of people coming to the country without authorization.

Source: Douglas S. Massey, Jorge Durand, and Karen A. Pren, “Why Border Enforcement Backfired,” American Journal of Sociology 121, no. 5 (March 2016): 1557–1600, doi:10.1086/684200.

This doesn’t mean that immigration enforcement efforts should stop, but focusing only on enforcement or one-time grants of legal status will not bring order to the border. Enforcement should prioritize the immigrants that are serious safety threats, and policymakers should create lasting pathways for those who came here illegally to pay compensation and regularize their status.

Drop the walls of red tape

Like the sand in your palm, the best approach to immigration reform is an openhanded system. Policymakers who want to control the border should start by making legal pathways wide and easily accessible.

Based on research, US policymakers have four promising steps to better its immigration system to the benefit of the entire country:

1. Simplify the green card application and approval process, including pathways for illegal immigrants to regularize their status (e.g., charging undocumented immigrants a penalty fee).

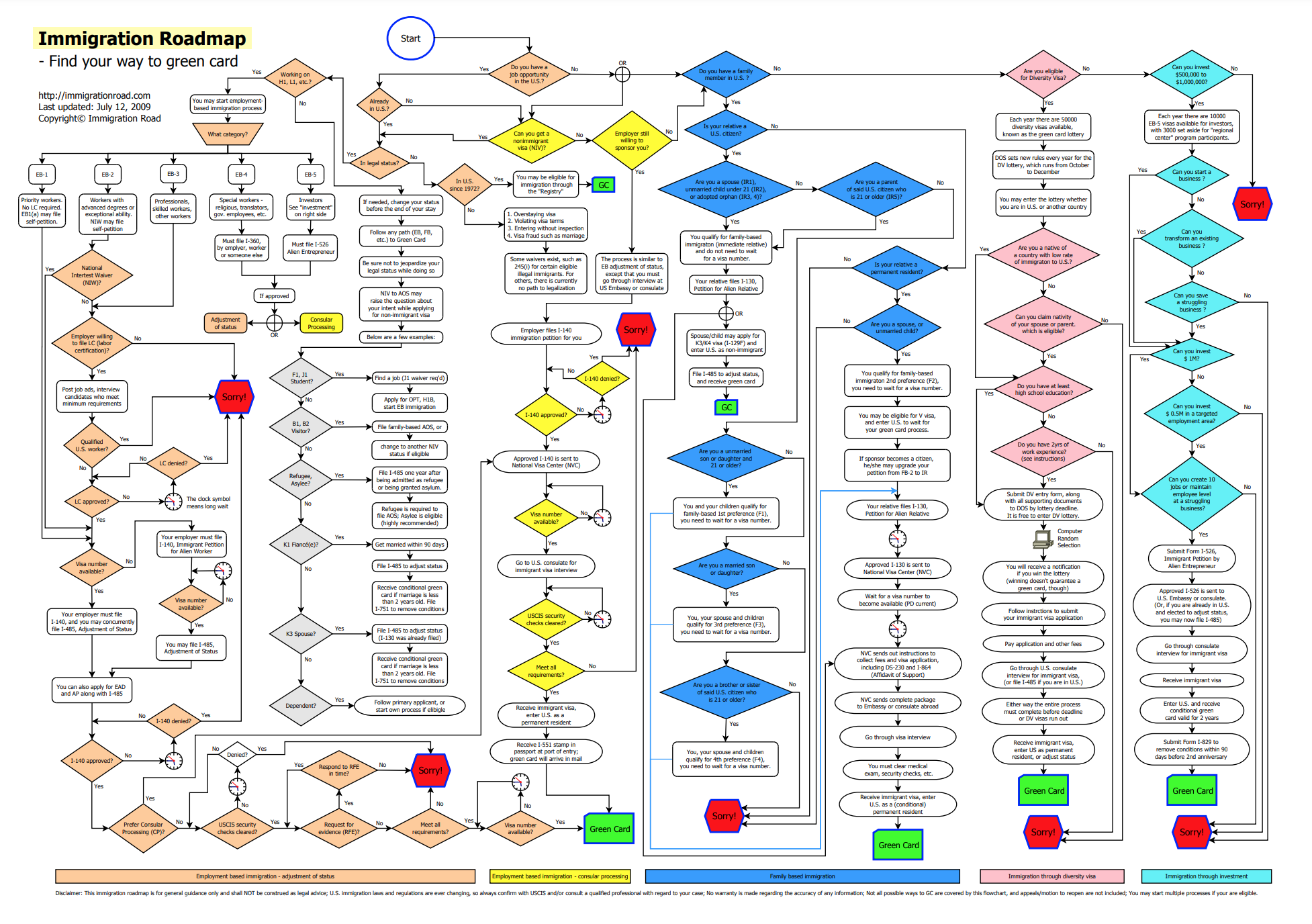

A large part of our illegal immigration problem is that the process for coming to the United States legally is too difficult for employers and immigrants. For example, Immigration Road’s flowchart for receiving a green card is a striking visual example of how our system makes legal immigration difficult.

Source: Immigration Road .

The government often fails to issue the green cards that it’s supposed to in a given year. For example, at the end of July 2021, an official with the Biden administration said that they will likely fail to use 100,000 green cards allocated for the year. Many immigrants wait months or years for a green card. As of October 1, it looks like around 80,000 of those visas will expire.

Unfortunately, this kind of administrative mishap in immigration policy is common. In a report for the Niskanen Center, immigration researchers Jeremy Neufeld, Lindsay Milliken, and Doug Rand estimate that as many as 940,699 green cards have not been issued but could have been. That’s almost one million people who could have come to the United States if the system worked more efficiently. A bill in Congress would recapture around 92,000 of these visas, around a tenth of those lost in the past. This is a good start, but it’s clear more will need to be done. For example, by making this a continuous process and removing the per-country caps on issuing green cards that others have proposed.

2. Treat US college degrees as visas.

Another red tape problem, current policy makes it difficult for international students who just spent four or more years earning a degree from a US university to stay in the country.

These students are gold mines, yet after they attend US universities, we send them away. Immigrants who earn a college degree are good candidates for keeping in the country for their economic benefits and talents. US policy should treat college degrees as visas or alter F-1 visas to automatically transition to green cards after completing a college degree.

3. Offer permanent status to children of legal international workers.

Current policy also makes it difficult for the international workers who bring their children to the United States to keep them here. A child originally sponsored by their parents ages out at 21. No matter their age when they arrive in the country, at 21 they have to leave or obtain a separate visa. That can mean children who have grown up in the country have no option but to leave.

Usually, these children are called “Documented Dreamers.” Organizations like Improve the Dream as well as legislation both in the House and the Senate aim to allow America’s international children to obtain green cards at 21 in recognition that they’ve grown up in the country.

4. Investigate better border control and enforcement methods that concentrate on dangerous individuals.

A promising example here is the Priority Enforcement Program. Research suggests that it creates trust within immigrant communities so that they will come forward to the police. In contrast to broad enforcement that concentrates mainly on low-level threats, these policies better promote public safety. The Biden administration recently directed agencies to implement similar changes.

Each of these recommendations offers a promising step towards reducing illegal immigration and investing in America’s economic future. Waiting to solve our border issue before creating any new immigration will only do more harm than good. Pathways for legal immigration will give policymakers a handle on today’s immigration problems and benefit the entire country.