Introduction

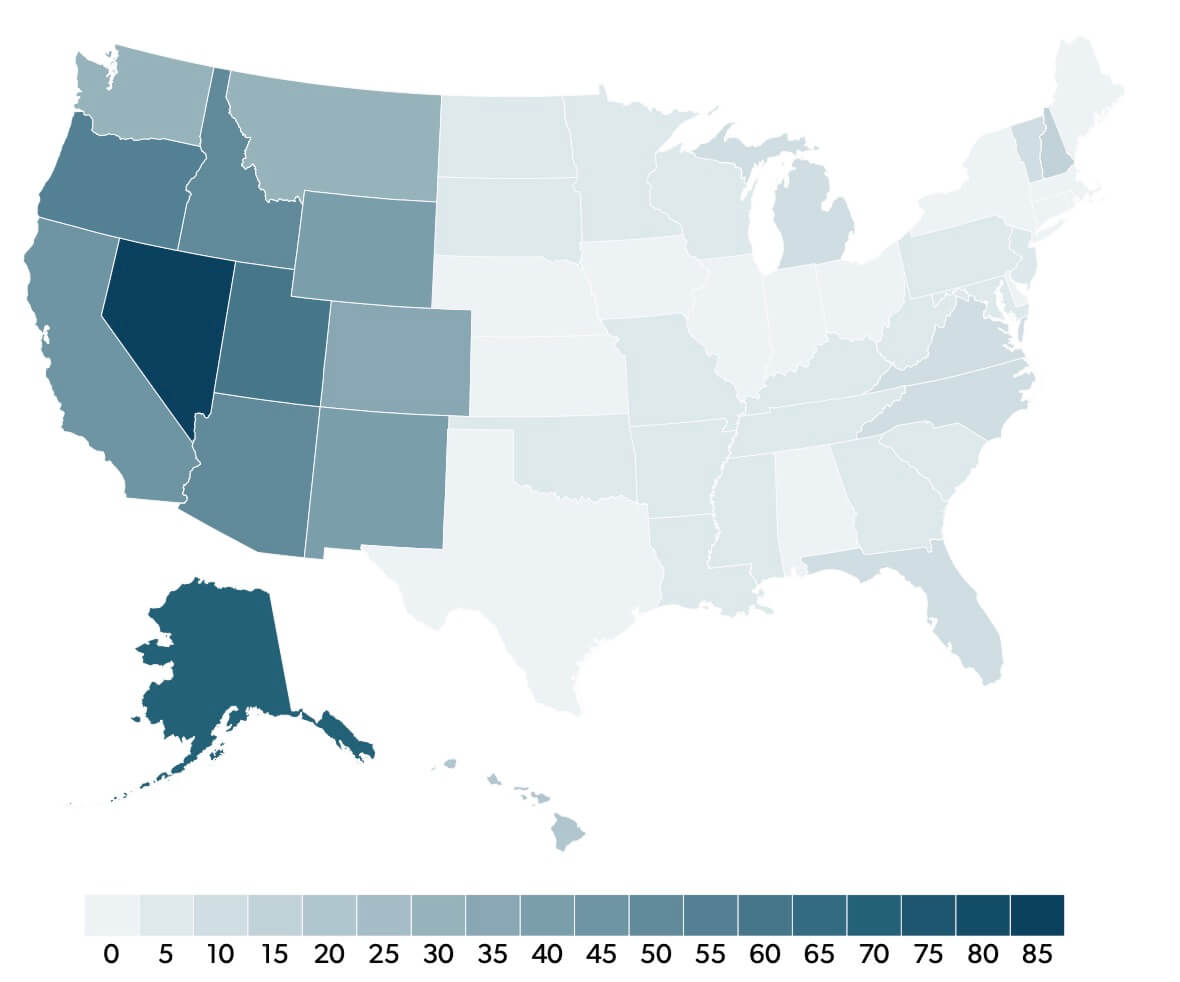

The federal government owns nearly 30 percent of all lands in the United States, and those lands generally are managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the Forest Service (FS), and the National Park Service (NPS). Each of those agencies falls under the administrative umbrella of the Department of the Interior (DOI) or the Department of Agriculture (USDA), and between them, they manage over 610 million acres of federal lands.1Carol Hardy Vincent, Carla N. Argueta, and Laura A. Hanson, “Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data,” US Congressional Research Service, March 2017, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42346.pdf.Figure 1 shows the percent of each state’s land area that is owned by the federal government. As the figure shows, federal lands are concentrated heavily in the western states.

Figure 1. Federal Land Ownership in the Western United States

Source: Carol Hardy Vincent, Laura A. Hansen, and Carla N. Argueta, “Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data,” Federation of American Scientists, Congressional Research Service, March 3, 2017, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42346.pdf.

Obtaining the funding needed to effectively manage such a large area has been a persistent problem. Each of the agencies responsible for managing federal land has a significant backlog of overdue maintenance projects. These maintenance needs are known as deferred maintenance, and together they form the maintenance backlog. The total maintenance backlog in 2019 was over $19 billion, with the largest share ($12 billion) held by the National Park Service (NPS).2US Congressional Research Service, “Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2009–FY2018 Estimates and Issues,” April 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43997.pdf.

Deferred maintenance can take many forms, including infrastructure repairs for roads, buildings, and other structures. Such deferred maintenance can result in damage to valued federal lands and can negatively impact the experiences of the millions of visitors who come to national parks and other federal lands every year. It can also cause environmental damage to public lands, which are often set aside specifically for conservation purposes.

For example, in 2019 the NPS outlined a plan to reconfigure and improve the parking at the Tuolumne Meadows Visitor Center in Yosemite National Park. According to the NPS, this improvement would reduce environmental damage by lowering the erosion caused by off-road parking that is negatively impacting water quality. If this improvement is not made, the National Park Service claims “the safety of visitors will continue to be compromised with increased pedestrian and vehicle traffic along the Tioga Road in congested areas.”3 US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, “Fiscal Year 2019 National Park Service Budget Justifications,” 2019, https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/upload/FY2019-NPS-Budget-Justification.pdf.

In addition to environmental sites, historical sites are also at risk of damage due to unmet maintenance needs. For example, the NPS plans to construct a new bulkhead at the Christiansted National Historic Site, which consists of several structures from 18th century colonial Virginia. The current bulkhead is old and does not comply with federal, state, or Coast Guard regulations. A new bulkhead would, according to the National Park Service, “eliminate safety hazard to employees and visitors,” “protect the park’s historic structures,” and “create recreational opportunities such as kayaking and paddle boarding.”4Ibid.

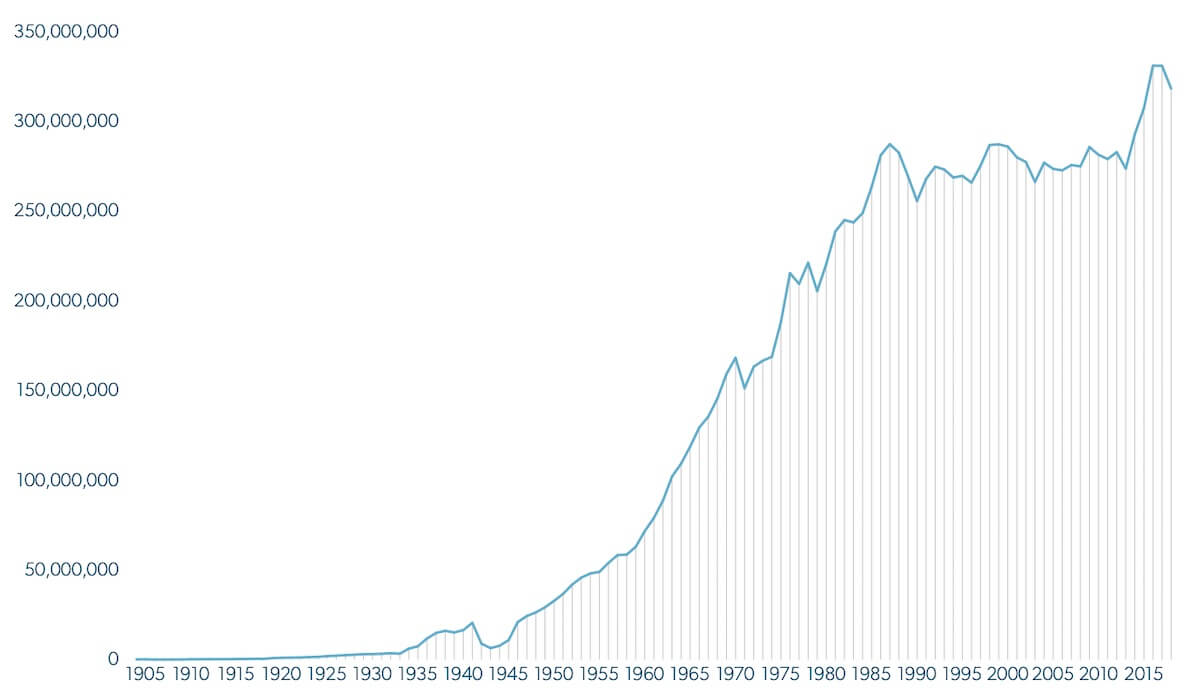

The deferred maintenance backlog has become an even more pressing issue as use of America’s federal lands continues to increase. As figure 2 shows, annual visitation to national parks has increased significantly since the mid-1900s. In 2018, national parks received more than 300 million visitors, which is roughly 33 million more than in 2009.5 Integrated Resource Management Application (IRMA) Portal, “Annual Visitation Report by Years: 2008–2018,” National Reports, National Park Service, accessed January 25, 2020. https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/SSRSReports/National%20Reports/Annual%20Visitation%20By%20Park%20(1979%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year). Unless effective policy solutions are implemented, deferred maintenance costs likely will continue to grow as more visitors create more wear-and-tear on roads, trails, and other resources in the parks.

Figure 2. Annual National Park Visitation (1905–2015)

Source: US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, “Fiscal Year 2019 National Park Service Budget Justifications,” 2019, https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/upload/FY2019-NPS-Budget-Justification.pdf

Effectively addressing the maintenance backlog could enhance the visitor experience by improving infrastructure, such as roads and bathrooms, that have fallen into disrepair. It also would help ensure that federal lands are being conserved properly.

In this policy paper we begin by examining how the maintenance backlog was created and why it has persisted over time. We then outline several solutions that potentially could be adopted to address the maintenance backlog. The solutions include giving park managers more control over entry fees, amending land acquisition policy to set aside money each year to be spent on deferred maintenance, and making use of concessionaire agreements to allow private companies to manage federal lands more effectively.

How was the backlog created?

One of the largest factors driving the maintenance backlog is the aging infrastructure in many of the parks across the country. Much of that infrastructure was built in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps, or by the National Park Service in the 1950s and 1960s under the Mission 66 program.6 Laura B. Comay, “The National Park Service’s Maintenance Backlog: Frequently Asked Questions,” US Congressional Research Service, August 23, 2017, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44924.pdf.

As park infrastructure has aged and parks have only increased in popularity, unmet maintenance requirements continue to pile up. While every agency has its own deferred maintenance backlog, the National Park Service backlog is the largest, at just over $11 billion in 2016.7US Congressional Research Service, “Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2009–FY2018 Estimates and Issues,” April 30, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43997.pdf.

The National Park Service does not report the amount spent on deferred maintenance every year. The US Government Accountability Office, however, estimated that the National Park Service spent an average of $1.16 billion per year from 2006 to 2015 on all kinds of maintenance, including deferred maintenance.8 US Government Accountability Office, “National Park Service: Process Exists for Prioritizing Asset Maintenance Decisions, but Evaluation Could Improve Efforts,” December 2016, https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/681581.pdf.

The sum of money needed to repair and conserve national parks continues to grow as infrastructure continues to age and park visitation continues to increase. In 2013, Jonathan B. Jarvis, then-Director of the National Park Service, testified before the US Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources regarding the growing deferred maintenance backlog. Jarvis claimed that, in order to keep the backlog at its current level, the NPS would need to spend $700 million per year. He also stated that in 2012 the NPS had spent only $444 million for that purpose.9Supplemental Funding Options to Support the National Park Service, Hearing before the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, United States Senate, 113th Cong. 20 (2013) (statement of Jonathan B. Jarvis, Director of the National Park Service).

Another factor contributing to growing maintenance needs in national parks is overcrowding. In both 2016 and 2017, national parks received over 330 million visitors—a record number of visitors. In 2017, visitors spent over 1.44 billion hours of recreation in the national park system, which exceed the prior year’s total by 19 million.10 US National Park Service, “National Park System Sees More Than 330 Million Visits,” news release, February 28, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1207/02-28-2018-visitation-certified.htm.

As visitation increases, parks have to deal with issues like waste management on a larger scale. For example, the National Park Service had to deal with almost 70 million pounds of waste in 2017.11 Karen Hevel-Mingo, “Working to Significantly Reduce Waste at National Parks,” National Parks Conservation Association, August 24, 2018, https://www.npca.org/resources/3243-working-to-significantly-reduce-waste-at-national-parks. During the federal government shutdown beginning in December 2018, many parks stayed open. However, without proper staffing, trash and waste piled up. This caused significant ecological damage and even forced some of the campgrounds at Joshua Tree National Park to close because of overflowing toilets.12Chris Boyette, “The Government Shutdown and Overflowing Toilets Force Joshua Tree National Park to Close,” CNN, January 2, 2019,

https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/01/us/government-shutdown-national-parks-toilets-services/index.html.

Additional visitors also increase the need for maintenance on park infrastructure like roads, bridges, and bathrooms. For example, Yellowstone National Park is served by two main roads, which provide access for more than 2 million vehicles annually.13Integrated Resource Management Application (IRMA) Portal, “Yellowstone NP: Annual Traffic Counts by Month,” STATS: Park Visitor Use Statistics, National Parks Service, accessed January 25, 2020. https://irma.nps.gov/STATS/SSRSReports/ParkSpecificReports/ParkAllMonths?Park=YELL. When many visitors travel through an area with limited roads, heavy wear and tear can result, making it even more difficult to access those areas to conduct needed maintenance.

According to the National Park Service, deferred maintenance needs for paved and unpaved roads comprised more than half of its $11 billion backlog.14National Park Service, “Servicewide NPS Asset Inventory Summary,” September 30, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/upload/NPS-Asset-Inventory-Summary-FY18-Servicewide_2018.pdf. Upkeep of deteriorating roads and bridges is also important for ensuring safety and maintaining operational efficiency for park visitors.15National Park Service, “Pavement Preservation: A Proactive Approach,” January 29, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/transportation/pavement-preservation.htm. Of the Forest Service’s 4,200 bridges, 11 percent have been deemed “structurally deficient’’ by the Federal Highway Administration, meaning they are in need of rehabilitation or have been restricted or closed.16 US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, “2015 Status of the Nation’s Highways, Bridges, and Transit: Conditions & Performance,” December 20, 2016, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/2015cpr/es.cfm; Virginia Department of Transportation, “Bridge Inspection: Definitions,” VDOT, n.d. https://www.virginiadot.org/info/resources/bridge_defs.pdf.

Overcrowding and deferred maintenance also can result in delays, especially for popular parks with many visitors. For example, Yosemite National Park alone receives 4 million visitors every year and advises potential summer visitors: “Expect delays of an hour or more at entrance stations and two to three hours in Yosemite Valley.”17National Park Service, “Traffic in Yosemite National Park,” May 7, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/traffic.htm. Such overcrowding also impacts the conservation efforts of national parks, as federal agencies have to combat invasive species that threaten the park’s ecosystem, maintain trails worn by use, and replant vegetation trampled by visitors.18 Meredith Rutland Bauer, “It Costs US National Parks Almost $1 Million a Year Each to Keep Looking Natural,” Quartz, October 14, 2016, https://qz.com/807018/national-parks-are-not-natural/.

Past efforts to address the backlog

Specific proposals to increase funding to land management agencies have been discussed several times, and some funding has been put towards the maintenance backlog. Despite this, direct, major action has not yet been taken.

In recent years, proposals by both President Obama and President Trump sought to increase funding for land management agencies. President Obama’s budget proposals for both Fiscal Year 2016 and 2017 included plans to raise funding for the National Park Service to fund upgrades and repairs to important infrastructure. The budget proposal highlighted the importance of maintaining national parks, especially prior to the National Park Service’s 100th birthday in August of 2016.19Office of Management and Budget, “Budget of the US Government Fiscal Year 2016,” 2015; Office of Management and Budget, “Budget of the US Government Fiscal Year 2017,” 2016.

Following those proposals, in December of 2016, Congress passed the National Park Service Centennial Act which created a special fund that reallocated at least $10 million of the revenue from Federal Recreation Lands Passes.20 National Park Service Centennial Act H.R. 4680, 114th Cong. (2016). The bill specified that none of that money was to go to acquiring new lands and that it all would be used to improve existing ones. Although this was a promising step, it equated to less than 1 percent of the overall deferred maintenance backlog.

In 2017 the National Park Service changed its park fee structure in an attempt to better address deferred maintenance needs. Most of the fee changes were minor increases of $5 to entrance fees at parks that already charge an entrance fee. The National Park Service stated that at least 80 percent of the money would stay in the park where it was collected to be used on projects to improve the visitor experience.21 National Park Service, “National Park Service Announces Plan to Address Infrastructure Needs & Improve Visitor Experience,” news release, April 12, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1207/04-12-2018-entrance-fees.htm. This small increase in fees is not likely to make a significant impact on the overall maintenance backlog.

In 2018, two bills had bipartisan support during the committee process, but were not passed. H.R. 6510 and S. 3172 sought to establish a “National Park Service Legacy Restoration Fund” with the specific goal of addressing the deferred maintenance backlog using revenues from energy development on federal lands and waters. Additionally, the bills required that no money from that fund be used for additional land acquisition.22Restore Our Parks and Public Lands Act, H.R. 6510, 115th Cong. (2018); Restore Our Parks Act, S. 3172, 115th Cong. (2018). The same bills were reintroduced to the 116th Congress in February of 2019 as H.R. 1225 and S. 500, respectively, where they await further action.23 Restore Our Parks and Public Lands Act, H.R. 1225, 116th Cong. (2019); Restore Our Parks Act, S. 500, 116th Cong. (2019).

More recently, President Trump’s proposed budget for Fiscal Year 2019 included the creation of a Public Lands Infrastructure Fund, which was never enacted, with specific goals for tackling the maintenance backlog accumulated by federal land management agencies. The plan proposed the use of revenue from energy leases on federal lands to provide up to $18 billion to the Department of the Interior for deferred maintenance.24 US Department of the Interior, “President’s $11.7 Billion Proposed FY 2019 Budget for Interior Includes Legislation to Strengthen

Infrastructure and Address Deferred Maintenance,” press release, February 12, 2018, https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/presidents-117-billionproposed-fy-2019-budget-interior-includes-legislation.

Bipartisan support exists for national parks generally and for taking action to address the maintenance backlog. According to surveys by the Center for American Progress (CAP), 77 percent of Americans believe the United States is better off with national parks and that repairing and restoring the national parks is a top priority. Another study by CAP shows that politicians who take a strong stand in support of national parks are significantly more popular among voters on both sides of the political spectrum.25Hart Research Associates, “Public Opinion on National Parks,” Center for American Progress, January 2016, https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/11070242/CAP_Polling-Slide-Deck-National-Parks2.pdf. While it is in most politicians’ interest to support bills protecting, repairing, or acquiring public lands, they often disagree on how those objectives should be accomplished. In addition, there is greater emphasis placed on acquiring new lands than on repairing and restoring public lands. This may be due to acquisition being a more visible signal to voters of the support a politician has for public lands, while repairs tend to be less visible.26William F. Shughart, “Katrinanomics: The Politics and Economics of Disaster Relief,” Public Choice 127, no. 1/2 (2006): 31–53. Even when money has been set aside for maintenance, funds tend to be diverted to other uses. In what follows, we explore policy options that could help address the maintenance backlog.

Option 1: Give park managers more control over entry fees

One policy option that could help address the maintenance backlog would be to give park managers more flexibility in determining park entry fees and more control over how those fees are spent. Under the current regulatory framework, park managers are not able to change the fees they charge visitors to account for fluctuations in demand. They also have limited ability to determine how funds raised in their park are spent. Giving park managers more control over park fees would help empower local managers to determine the appropriate level at which fees should be set and how best to use fees to address ongoing maintenance needs.

Under the current National Park Service entry fee system, parks are grouped into four different categories.

The categories were created by the National Park Service in 2006 in an attempt to simplify and standardize park fee structures.27National Park Service, “Your Fee Dollars at Work,” updated November 21, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/fees-at-work.htm. The categories roughly correspond to the park sizes and maintenance requirements. The smallest entry fees belong to the smallest NPS sites, including national historic sites, battlefields, and memorials. The next group includes larger areas, including national seashores, recreation areas, and monuments. Finally, the last two groups are comprised of national parks. Of the 419 parks operated

by the NPS, only 111 of them charge any entry fee.28 National Park Service, “Entrance Fees by Park,” updated December 23, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/entrance-fee-prices.htm

A 2015 report from the Office of the Inspector General for the US Department of the Interior outlines the layers of internal review required to change the fee category into which a particular park falls. The authors suggest that such a burdensome and lengthy process likely caused parks to decide not to update or change their fee levels.29 Office of the Inspector General, US Department of the Interior, “Review of National Park Service’s Recreation Fee Program,” February 19, 2015, https://www.doioig.gov/reports/review-national-park-services-recreation-fee-program.

The report highlights Lake Mead National Recreation Area, which tried to raise its entry fees in two phases, and received approval for the first increase after completing the regulatory process. However, the area’s managers later were informed that they would have to restart the process if they wanted to implement the second phase of the proposed fee increase. Park staff “simply did not have the time or resources to go through the process again.”30Ibid.

The current system prevents park managers or superintendents from making decisions about the appropriate level of entry fees to a particular park. If the National Park Service were to implement a park-by-park program that allows for flexible pricing schemes, then park managers would be able to adjust entry fees based on demand, the maintenance needs of individual parks, and different recreational uses.

Holly Fretwell and Shawn Regan of the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) outline the importance of allowing park managers and agencies to adjust their fee systems, or institute new ones, without congressional approval. Fretwell and Regan suggest that, similar to changing the designation of the park, the process of revising fees is so difficult that some park managers who wanted to update their park’s fee schedules simply gave up on the idea.31Shawn Regan, Reed Watson, Holly Fretwell, and Leonard Gilroy, “Breaking the Backlog: 7 Ideas to Address the National Park Deferred Maintenance Problem,” Property and Environment Research Center, February 16, 2016, https://www.perc.org/2016/02/16/breaking-thebacklog-2/.

One potential concern with allowing park managers to adjust fees more easily is that low-income visitors may be priced out of the parks. PERC scholars suggest that increasing park fees likely would not result in a significant reduction in visitors, as park fees are only small fractions of the total people spend on park visits. Compared to the costs of food, lodging, and transportation, park fees are minimal. According to reports that studied Yellowstone and Yosemite National Parks, entry fees made up less than 2 percent of the average total costs of visiting a park.32Ibid. This suggests changing park fees would not be likely to affect most visitors’ decision about whether to visit a park. It would, however, give park managers greater ability to raise funds to dedicate to maintenance needs in their parks.

Most entry fees are already required to stay in the park where they were collected. The Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act provides that at least 80 percent of entry fees must be used in the specific area where they were collected.33Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement, 16 U.S.C. § 87 (2004). That rule allows park managers to address maintenance requirements through entry fees, especially if paired with a flexible entry fee system. If park managers could experiment to find the most efficient entry fee for their particular park, they would receive a large portion of that fee revenue back that they could then use for maintenance needs. If a park had an important infrastructure issue and needed to raise revenue to compensate for that, park managers would be able to adjust the entry fee upward.

PERC scholars have also suggested using the entry fee system as a tool to help with park funding. In a 1997 piece titled “Back to the Future to Save Our Parks,” the authors highlight the ability for parks to use a fee system to become much more self-sufficient.34Donald Leal and Holly Fretwell, “Back to the Future to Save Our Parks,” Property and Environment Research Center, June 1, 1997, https://www.perc.org/1997/06/01/back-to-the-future-to-save-our-parks/. Park managers could use entry fees to fund individual deferred maintenance projects that they know are necessary for their park and then continue to use congressional funding to defray the majority of the park’s other costs. The authors suggest that park managers should be allowed to institute their own fee programs and tailor their fee systems to park needs. Additionally, they suggest that nearly all of the revenues collected from the fee system should be kept within the park so that managers can utilize the fee system to more directly meet funding needs.

Other scholars have also suggested allowing more flexible pricing for parks. A 2019 report commissioned by the Pew Charitable Trusts outlines a dynamic pricing system in which fees would increase during the busiest times of the year. The authors claim that a flexible pricing strategy could increase National Park Service revenues substantially and potentially provide $1.5 billion in revenues over the next 10 years, some of which could be used to help address the maintenance backlog.35AECOM, “Protecting Our Parks: A Strategic Approach to Reducing the Deferred Maintenance Backlog Facing the National Park Service,”Pew Charitable Trusts, Spring 2019, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2019/05/protecting-our-parks-report_low-res.pdf.

Flexible fee systems would also give park managers a tool for more effectively managing the numbers of park visitors. Just as park fees would increase on the busiest days to limit visitors and reduce overcrowding, park managers could reduce fees during the offseason to attract more visitors to the park. More flexible pricing for parks thus would help regulate overcrowding by encouraging some visitors to adjust the timing of their visits.

Option 2: Allocate LWCF funds for maintenance needs

A second policy option for solving the maintenance backlog is to amend the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) to dedicate some of its funding specifically to deferred maintenance on federal lands. The LWCF was established in 1964 for the purpose of financing federal land acquisitions.36Carol Hardy Vincent, “Land and Water Conservation Fund: Overview, Funding History, and Issues,” Congressional Research Service, June 19,

2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33531.pdf. After being extended several times by Congress, the LWCF was reauthorized permanently in March of 2019.37National Park Service, “History of the LWCF,” Land and Water Conservation Fund, March, 20, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/lwcf/lwcfhistory.htm The LWCF is used primarily by the Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, Forest Service, and National Park Service, which collectively manage more than 95 percent of the 640 million acres of total land owned by the federal government.38 Carol Hardy Vincent, Carla N. Argueta, and Laura A. Hanson, “Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data,” US Congressional Research Service, March 3, 2017, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42346.pdf

The LWCF raises $900 million annually, most of which comes from oil and gas leases on the Outer Continental Shelf.39 US Department of the Interior, “LWCF Overview,” Land and Water Conservation Fund, n.d., https://www.doi.gov/lwcf/about/overview Since the fund’s inception, the full $900 million has been appropriated for its intended use in only two years. Since 1964 there were fewer than 10 years in which $500 million or more was spent from the LWCF.40Carol Hardy Vincent, “Land and Water Conservation Fund: Overview, Funding History, and Issues,” Congressional Research Service, June 19, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33531.pdf.

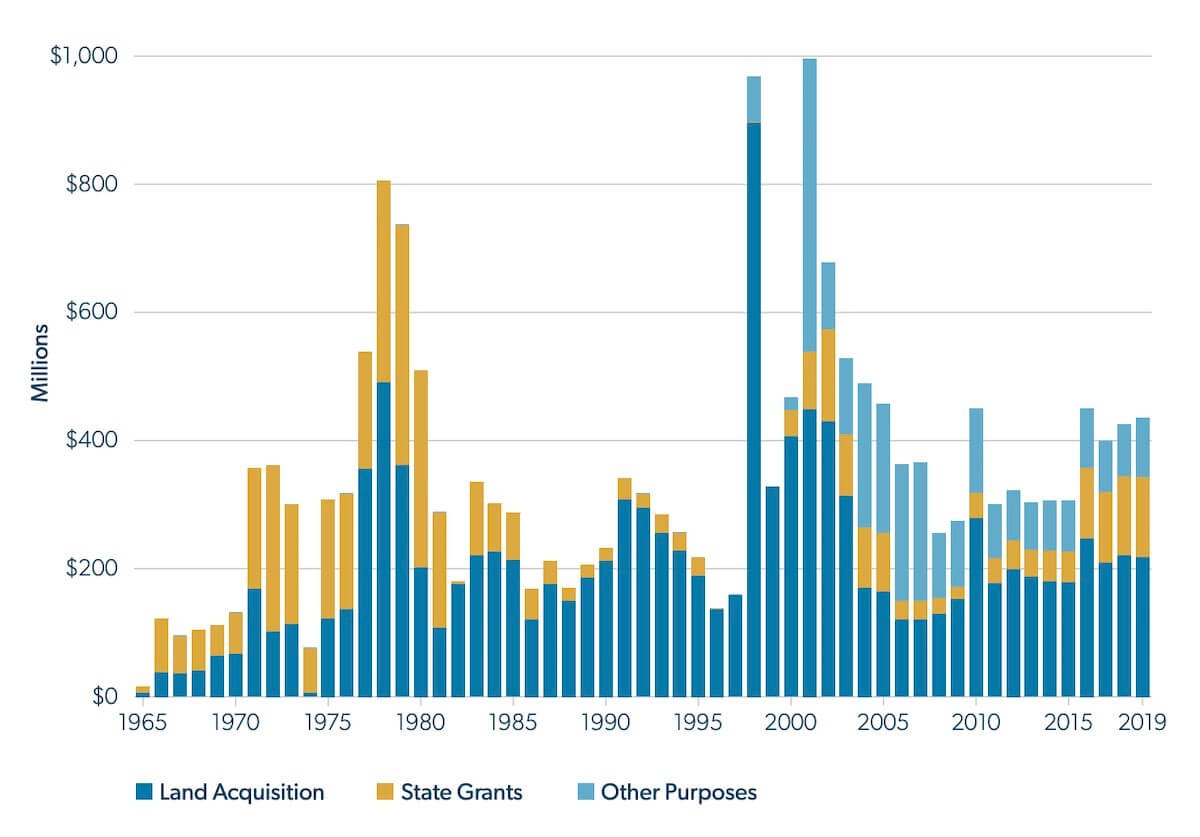

the LWCF is primarily used to acquire additional federal lands, the fund also assists states with outdoor recreation programs by establishing a grant system aimed at planning, acquiring, and developing outdoor recreation and conservation areas. Thus far, most of the fund’s allocated revenues have been spent to acquire new federal lands, leaving little room for maintenance.41Ibid. Figure 3 shows a breakdown of the distribution of LWCF revenue every year from 1965 to 2019.

Figure 3. LWCF Annual Discretionary Appropriations (in millions of dollars, not adjusted for inflation)

Source: Carol Hardy Vincent, “Land and Water Conservation Fund: Overview, Funding History, and Issues,” Congressional Research Service, June 19, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33531.pdf

Of the total of $18.4 billion that has been dispersed from the fund through 2018, $11.2 billion has been appropriated for federal land acquisition. State grant programs, the second largest appropriation from the fund, have received $4.7 billion over the same period.42 Carol Hardy Vincent, “Land and Water Conservation Fund: Appropriations for ‘Other Purposes,’” Congressional Research Service, August 27, 2018, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44121/7.

The remaining $2.6 billion have financed various smaller projects, including maintenance and infrastructure, which are included in “other purposes.”43Ibid. That category also includes things like the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund, which received roughly $50 million in 2004. The FWS contributes out of those monies to state-level endangered species and habitat conservation efforts on non-federal lands.44 US Fish and Wildlife Service, “Grants: Overview,” Endangered Species, updated October 2, 2019, https://www.fws.gov/endangered/grants/. No specific amount of the LWCF’s revenue is currently dedicated to deferred maintenance in the “other purposes” category, although when money is spent on deferred maintenance, it is included in that budget item.

While some LWCF money has been appropriated for maintenance purposes in the past, setting a minimum threshold or a specific dollar amount would provide more consistent funding to address ongoing maintenance needs. In most years, less than half of the LWCF’s annual revenues are appropriated. Federal land management agencies cannot make major changes in the way LWCF funds are distributed, but Congress could amend the LWCF to enable land managers to put LWCF funds to use to address deferred maintenance needs.

Amending the LWCF to help address the maintenance backlog on public lands has been discussed by Congress before. In 2015, the fund’s enabling legislation expired, requiring new legislation to be passed for it to continue. When debating the LWCF’s reauthorization before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Senator Lisa Murkowski, then the committee’s chair, stated, “As we look to reauthorize LWCF, I believe that it makes sense to shift the federal focus away from land acquisition, particularly in Western states, toward maintaining and enhancing the accessibility and quality of the resources that we have.”45Reauthorization of and Potential Reforms to the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), Hearing before the Committee on Energy and Natural

Resources, United States Senate, 114th Cong. (2015) (statement of Senator Lisa Murkowski, Chairperson of the Committee on Energy and Natural

Resources). She highlighted the fact that federal agencies own significant fractions of land in the Western United States, but that the same federal land management agencies are responsible for billions of dollars in unmet deferred maintenance projects.

Using the LWCF to protect and conserve lands that the federal government already owns would help achieve the fund’s original mission of protecting lands for recreation and conservation.

Option 3: Focus on maintenance over acquisition

A third policy solution that could help address the maintenance backlog on federal lands would be to amend the Federal Land Transaction Facilitation Act to allow some of the funds raised from selling federal lands to be used to address maintenance needs.

Some scholars argue that the federal government should reduce its focus on new land acquisition and instead focus on protecting the lands it already owns. Shawn Regan and Reed Watson from PERC argue that the focus on new land acquisition rather than maintenance hinders the ability of federal agencies to protect existing lands and creates future costs because acquiring more land requires more maintenance.46 Shawn Regan, Reed Watson, Holly Fretwell, and Leonard Gilroy, “Breaking the Backlog: 7 Ideas to Address the National Park Deferred

Maintenance Problem,” Property and Environment Research Center, February 16, 2016, https://www.perc.org/2016/02/16/breaking-thebacklog-2/.

The Federal Land Transaction Facilitation Act (FLTFA) authorizes the Bureau of Land Management to sell federal lands identified for disposal by land-use plans for the purpose of purchasing new lands deemed as having a high conservation value.47US Congress, Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Federal Land Transaction Facilitation Act Reauthorization: Report (to accompany S. 368), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CRPT-113srpt61/html/CRPT-113srpt61.htm. The revenues are also used to purchase small parcels of private land within the borders of larger federal land tracts, such as national parks.

The FLTFA allows the BLM to consolidate federal lands, increasing the efficiency of conservation resources, and to dispose of land that “is difficult and uneconomic to manage, is no longer required for a federal purpose, and will serve important public objectives if disposed of.”48Congressional Research Service, “Federal Land Transaction Facilitation Act: Operation and Issues for Congress,” December 10, 2012, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20121210_R41863_48c9fcb46ebeea51981d85a1e0895e88748c5457.pdf.

The FLTFA gives the federal government another land acquisition tool. However, the acquisition of high conservation value lands is already a key goal of the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Congress could amend the FLTFA so that some of its revenues finance deferred maintenance projects in national parks rather than being used solely for land acquisition. The goal of purchasing high-priority lands for conservation purposes could still be accomplished by the LWCF, while a portion of the FLTFA’s revenue could specifically target maintenance requirements.

The land sales authorized by the FLTFA generated more than $100 million for the BLM between 2000 and 2010.49Ibid. Designating some percentage of revenues received through the FLTFA for maintenance and infrastructure is another promising tool policymakers could utilize to address the maintenance backlog.

Option 4: Expand the use of private concessionaires

A fourth potential policy solution to help address the maintenance backlog on federal lands would be to expand the use of public-private partnerships in managing those lands. Through concessionaire agreements, private companies enter into contracts with the federal government to provide specific services at federal sites. Such services can include managing campgrounds or operating lodges, restaurants, or campgrounds. Companies entering into private concessionaires have a financial incentive to provide the best possible visitor experience and to address maintenance needs as they arise.

Concessionaires and agencies must agree on a plan that lays out the details of operating the concession in line with agency standards. Private concessionaires charge entry fees and use the resulting revenues to maintain the areas they are responsible for managing. A share of the entry fee revenues go directly to the government in the form of rent, while the rest is spent at the discretion of the private manager.

The Forest Service has made use of concessionaire agreements for decades to manage many recreation areas across the United States. Public-private partnerships for park management were first adopted by the Forest Service in the 1980s to keep parks open in the wake of budget cuts. Over half of the Forest Service’s thousands of recreation areas are managed under private concessionaire agreements.50Leonard Gilroy, Harris Kenny, and Julian Morris, “Parks 2.0: Operating State Parks through Public-Private Partnerships” (Policy Study 419,

Reason Foundation, Los Angeles, CA, November 2013), https://reason.org/wp-content/uploads/files/state_parks_privatization.pdf.

For example, many ski resorts across the United States operate on Forest Service land under similar lease agreements. While some resorts own the land they operate on directly, others have entered into lease agreements with federal land management agencies or private landowners. Companies that operate the resorts own their equipment and infrastructure, but the land itself is owned by other parties. Of the 476 ski resorts in the United States during the 2018–2019 season, 122 of them operated on Forest Service land.51 National Ski Areas Association, “Number of Ski Areas in Operation 1991-92 to 2018-19,” NSAA Industry Stats, August 2019, http://www.nsaa.org/media/367755/ski_areas_per_season_1819.pdf; Greg M. Peters, “The Future of Ski Resorts on Public Lands,” Your National Forests Magazine, Winter/Spring 2014, https://www.nationalforests.org/our-forests/your-national-forests-magazine/the-future-of-ski-resorts-on-publiclands Many of these resorts have successfully operated on federal land since the mid-1900s.52Richard A. Lovett, “The Role of the Forest Service in Ski Resort Development: An Economic Approach to Public Lands Management,” Ecology Law Quarterly 10, no. 4 ( January 1983), https://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/elq/vol10/iss4/1/.

Concessionaire agreements have also been used at the state level to help keep parks open in the face of financial strain. In 2011, California announced the planned closure of 70 state parks due to funding cuts. In an effort to keep some of these parks open, the California Department of Parks and Recreation established partnerships with external entities to prevent the shutdowns. Partnerships with private concessionaires and non-profits, in addition to agreements with outside donors and municipal governments, allowed the state to keep 69 of its 70 parks open.53 Gilroy et al., “Parks 2.0.”

Another example of private concessionaire agreements is at Crescent Moon Recreation Area in Arizona. A 2011 case study by Recreation Resource Management compared Crescent Moon, which is run privately, to the nearby publicly owned and operated Red Rock State Park.54Ibid. The two parks are similar in location, size, and in the numbers of visitors and revenues generated. The case study finds that Crescent Moon brings in roughly $45,000 every year for the Forest Service. Red Rock State Park, on the other hand, loses about five times that sum every year for Arizona’s state park system.55 Recreation Resource Management, “A Tale of Two Parks: Keeping Public Parks Open Using Private Operations Management,” case study, 2011, https://camprrm.com/how-we-work/case-study/. Although it is just one example, the success seen by the privately operated park suggests that the concessionaire system could be an important tool for improving park quality while avoiding large taxpayer-financed expenditures.

Other groups have also suggested that expanding the private concessionaire program could help ensure park quality and generate substantial revenues for federal land management agencies. For example, the American Society for Civil Engineers suggested that the federal government should “[l]everage partnerships between the National Park Service and other recreation facilities operators and private groups to better utilize facilities and compensate for usage” in the Public Parks section of its 2017 Infrastructure Report Card.56 American Society of Civil Engineers, “Parks: 11.9 Billion in National Park Service Deferred Maintenance,” in 2017 Infrastructure Report Card, released March 9, 2017, https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Parks-Final.pdf.

Public-private partnerships such as concessionaire agreements are important models that can help maintain park quality while also leveraging the private sector’s experience in effective cost management. Concessionaire agreements are unlikely to eliminate the backlog entirely. They may be helpful, however, in reducing the size of the backlog and slowing its future growth by creating incentives to address maintenance needs today.

Conclusion

Reducing the maintenance backlog on America’s federal lands will enhance the visitor experience and help ensure that America’s public lands are effectively preserved. It will also help to ensure visitor safety by maintaining roads, bridges, and other necessary structures. Finally, addressing important maintenance needs is crucial if federal agencies are to achieve their conservation goals and protect sensitive areas from environmental damage.

The policy options offered here provide several options for addressing the maintenance backlog on federal lands. Providing local park managers with the ability to experiment with flexible fees, directing money from existing land management funds, and utilizing private concessionaire agreements are all promising options to reduce the maintenance backlog and help ensure that federal lands are cared for effectively.

Whatever solution policymakers choose, action should be taken quickly if the maintenance backlog is to be addressed effectively. By choosing one option or a portfolio of options, policymakers can help solve the issues that deferred maintenance creates and prevent them from becoming worse. Addressing the current failure to maintain public parks will be crucial in ensuring that America’s public lands are preserved for future generations to enjoy.

Morning Consult

Morning Consult The Gazette

The Gazette MDPI

MDPI