1 Introduction

Cultural diversity is evident within and between countries, and it is widely recognized for its strong correlation with economic and political development (see, e.g., Nunn 2021). According to cultural geographer Wilbur Zelinsky, “the dominant culture of a given nation is determined by the characteristics of the first group of settlers who came to an empty territory regardless of how small the initial band of settlers might have been” (Zelinsky 1973).

To understand the influence of immigrants on the cultural and institutional evolution of settler societies, in this paper I revisit Zelinsky’s doctrine. I place specific emphasis on settlers’ culture as a pivotal element of their characteristics and assess its impact in explaining variations in gender norms within the United States, particularly within individual states. My approach hinges on exploiting the disparities in early settlers’ attributes across US counties, generated by immigration from places with distinct gender norms. This analysis seeks to determine whether early settlers carry and instill their values and beliefs in the newly established areas of the United States. I document higher female labor force participation (FLFP), both historically and currently, in US counties that historically hosted a larger share of settlers from origins with liberal gender attitudes. I also find that current residents of these US counties have liberal attitudes toward women’s roles in societies.

This paper centers on gender norms, encompassing beliefs and values concerning women’s roles in society, which exhibit significant disparities both among and within states. Survey-based measures, such as the General Social Survey (GSS), unveil substantial variations in gender roles and attitudes among respondents in the United States. Furthermore, by concentrating on gender norms, I can offer indicative evidence supporting potential mechanisms pertaining to the development and transformation of gender values and beliefs in US counties. These mechanisms are linked to gender attitudes in the settlers’ places of origin (see Sections 2.2 and 3 for details).

I examine the US context and identify the settler population by analyzing data concerning individuals who resided in US counties around the time of their establishment. These settlers encompass individuals born in the same state, those from other states, and those born outside of the United States. My focus centers on US counties that were created during the “age of mass migration,” a period characterized by a substantial influx of diverse migrants to the United States between 1850 and 1940. This choice is informative for several reasons. First, it enables me to study counties during their early stages of cultural and institutional development. Second, the era of mass migration offers an adequate setting for examining variations in the composition of settlers, both across and within states, due to the extensive and varied migration flows into the United States during that time.

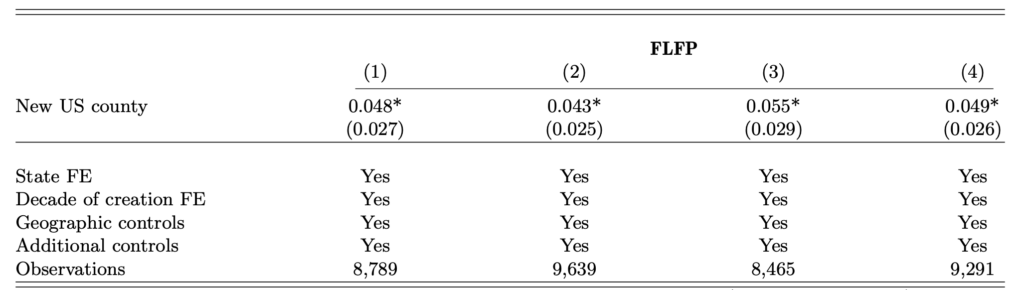

To understand the outsize influence of settlers during the initial stages of institutional development, I distinguish between two categories of newly formed US counties: “new” and “partitioned” counties. My primary sample of newly established counties—referred to as new counties—consists of those that were not created through partitioning or division from previously established counties but instead originated from areas that were not part of any county. In an alternative analysis, I consider counties that were partitioned from preexisting settled regions, referred to as partitioned counties.

The rationale behind this distinction is rooted in the notion that new counties might significantly differ from partitioned counties in terms of their level of establishment and development, encompassing factors related to county, community, society, culture, and institutions. Consequently, new counties are more representative of the “empty” territories alluded to in Zelinsky (1973)’s doctrine. A key distinguishing characteristic between new and partitioned counties is that the latter were densely populated. This presents an empirical framework to examine the cultural legacy of first effective settlement and directly assess Zelinsky (1973)’s doctrine, which contends that “the actions of this initial group of people have a much more significant impact on the cultural landscape of a region than the contributions of tens of thousands of new immigrants several generations later.” This approach aligns with theories of persistence through intergenerational cultural transmission, path dependence, and the pivotal role of initial conditions during critical junctures of institutional development in shaping social norms and attitudes, both in the short and long term (Alesina and Giuliano 2015; Bisin and Verdier 2017; Belloc and Bowles 2013; Bazzi et al. 2020; Couttenier et al. 2017; Tabellini 2008).

To examine the makeup of settlers, I analyze data on their demographic attributes, place of birth, and gender-related characteristics in their places of origin. To capture settlers’ culture, I employ quantitative measures that reflect values and beliefs originating from their places of birth. The fundamental premise here is that settlers internalize their cultural norms before relocating to new areas, establishing a connection between settlers’ culture and the prevailing culture in their home country or state. I present supportive evidence for this assumption in Section 6.

I begin by presenting a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of early settlers who resided in US counties around the time of their creation. My findings reveal that most of these settlers were literate men in their prime working years. Most were born outside of the state where they settled, followed by those born within the state and those born abroad. In terms of settlers’ cultural background, foreign-born settlers predominantly hailed from high-FLFP countries, defined as those with above-median FLFP rates. Meanwhile, out-of-state born settlers predominantly came from states where women had property and earning rights.

My analysis of the role of settlers’ culture in explaining variations in FLFP within states yields compelling evidence supporting the concept of cultural continuity and the persistence of norms over time, particularly within the primary sample of new counties. I establish a positive and statistically significant link between FLFP in newly established US counties, both in the short and the long term, and the cultural values of the initial settlers. These values are represented by factors such as historical FLFP (measured using various metrics) and women’s financial liberation in the settlers’ places of origin.

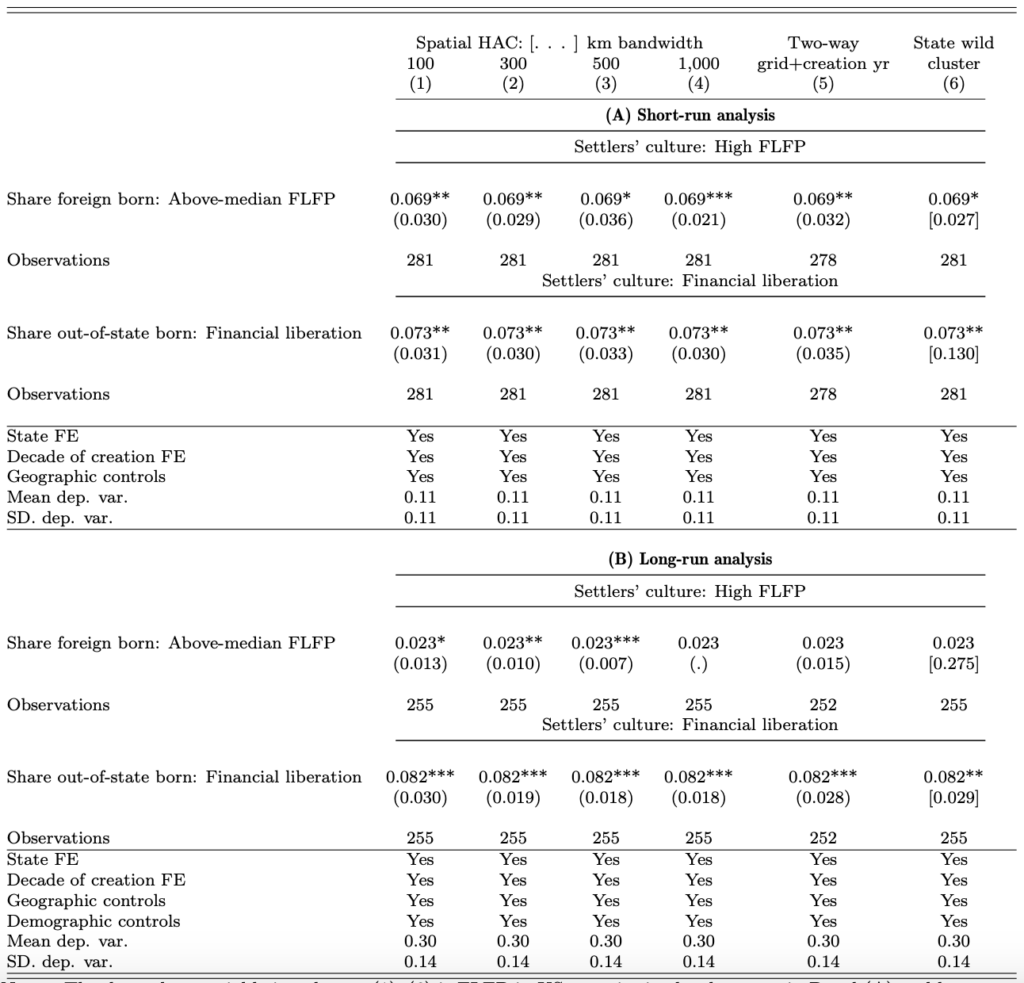

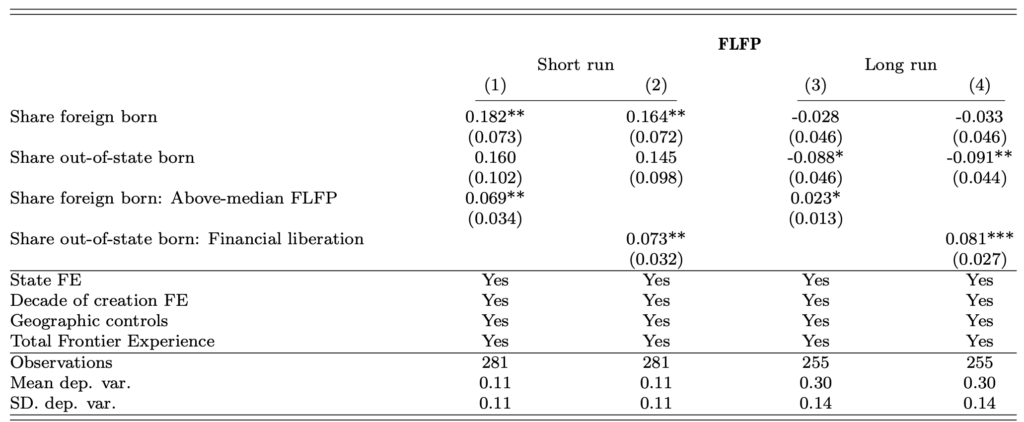

I conduct a comprehensive sensitivity analysis and demonstrate the robustness of the results to various modifications, including changes in the measurement of settlers’ culture, the consideration of demographic characteristics within counties, the inclusion of additional county-level factors pertaining to isolation and economic development, the use of alternative inference methods, and the incorporation of controls for counties’ frontier experiences.

However, when I focus on the alternative sample of partitioned counties, this relationship is not observed. I attribute this difference to the fact that partitioned counties are not in their earliest stages of development and do not experience the same critical junctures in the formation of their local culture.

Comparing the results obtained for newly created counties emerging from noncounty areas (new counties) with those from subdivisions of existing counties (partitioned counties) aligns with conducting a differences-in-differences analysis. The findings corroborate the predictions made by Zelinsky (1973) that the influence of settlement is considerably stronger when cultural institutions have yet to take shape. This phenomenon explains the significant impact of early settlers in new counties during crucial phases of cultural and institutional development, where the initial settlers shape local institutions and culture. These influences became entrenched norms, as opposed to the more advanced and established communities in partitioned counties. This innovative research framework thus serves as a practical means to empirically examine and document one of the potential mechanisms through which persistence may have occurred.

The main challenge in achieving causal identification stems from omitted variables that exhibit correlations with both the county-level proportions of settlers from regions with liberal gender attitudes and FLFP in newly established US counties. To address the potential issues of selection and sorting of settlers into newly created US counties based on specific local conditions, as well as the self-selection of settlers with particular characteristics, including gender-related values, I incorporate a set of covariates that are likely to impact both the composition of settlers and gender norms within US counties. These covariates account for local factors such as economic opportunities. Additionally, I implement an instrumental variables (IV) strategy designed to isolate potentially exogenous variations in settlers’ culture.

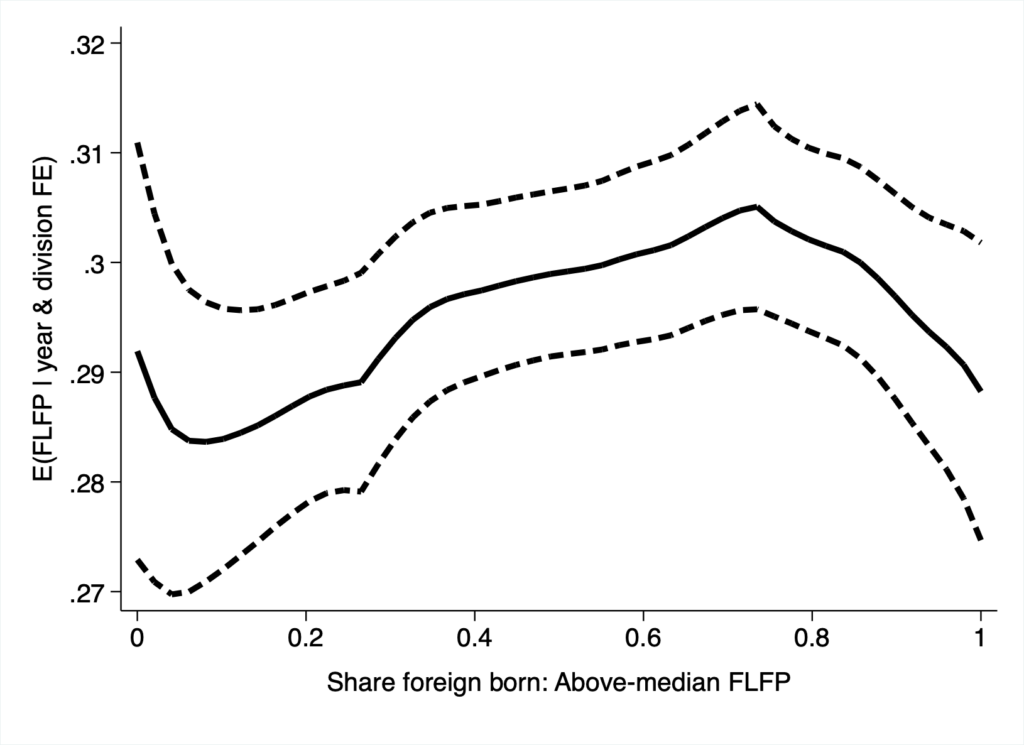

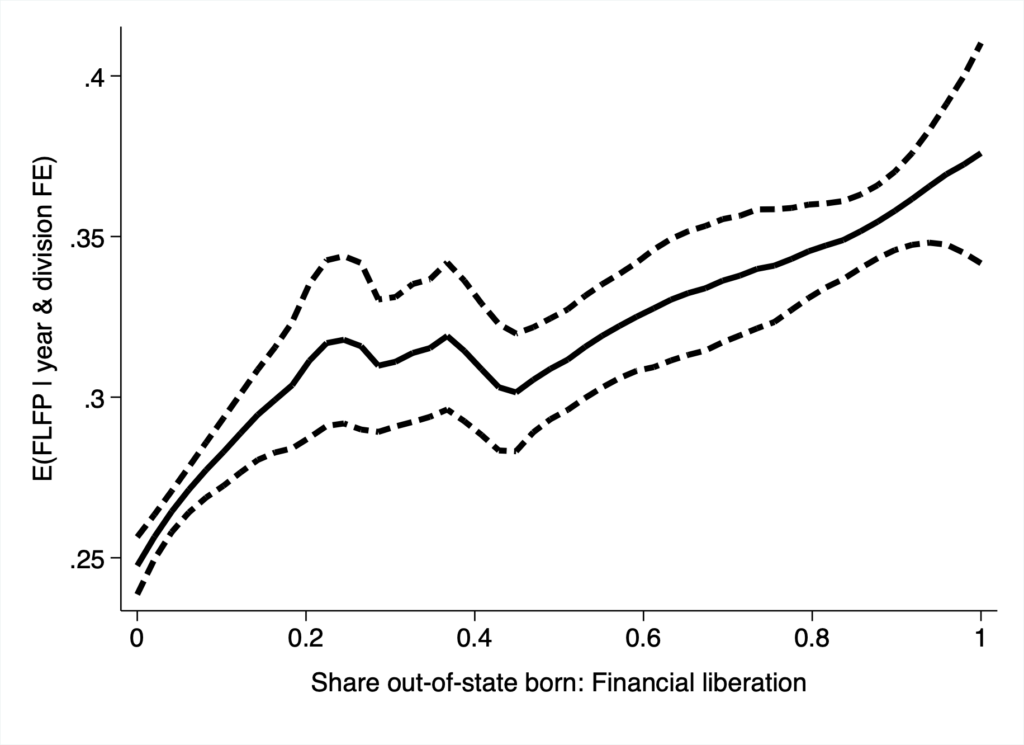

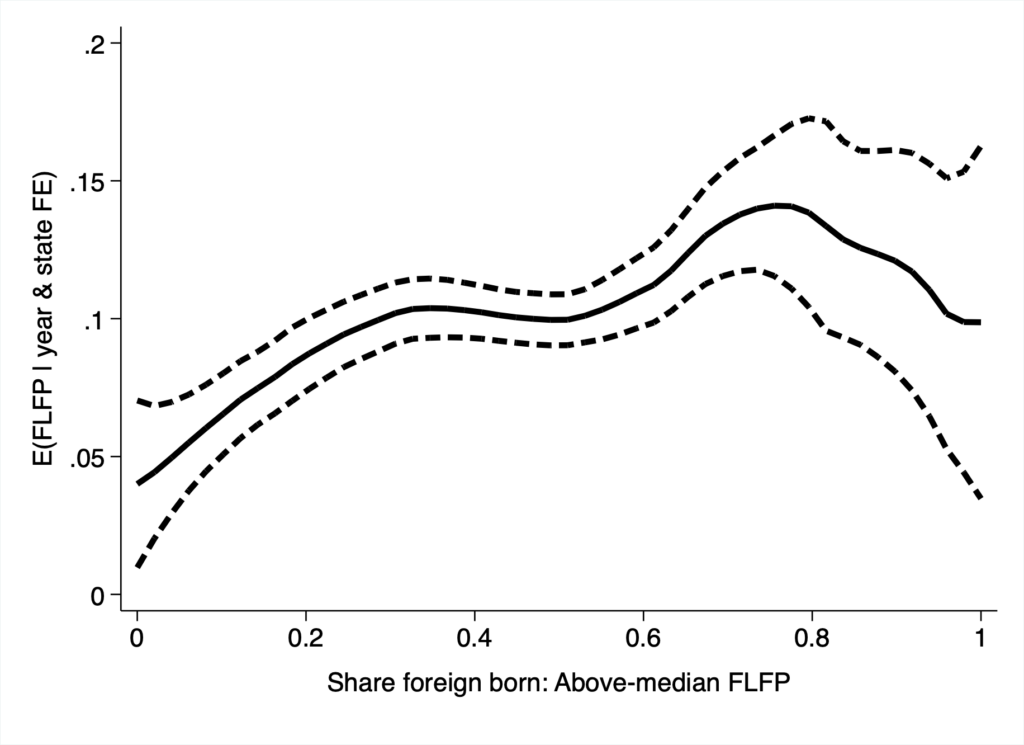

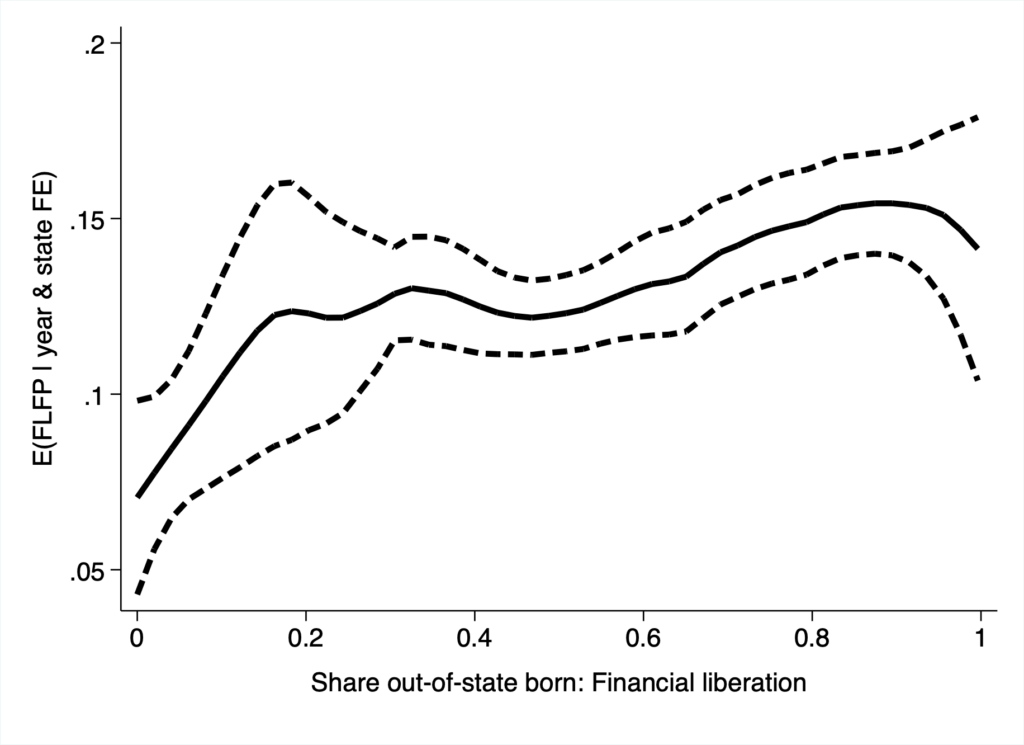

I tackle further potential threats to the study’s identification as well as various other issues and concerns that encompass potential limitations in quantifying settlers’ populations, the link between the timing of county formation and settler populations, migration endogeneity, and the validity of the cultural correspondence assumption. Moreover, I examine the factors influencing the enduring influence of initial cultural elements by exploring the nonlinear impacts of settlers’ culture on FLFP in recently formed US counties. I uncover structural shifts in FLFP levels within US counties with historical ties to settlers, both in the short and long run, revealing the presence of threshold effects in the transmission of cultural values.

I next investigate whether the culture of later settlers plays a significant role in cultural development within host areas. My findings indicate that the influence of initial settlers is considerably more significant for cultural formation compared to the contribution of new immigrants arriving several generations later.

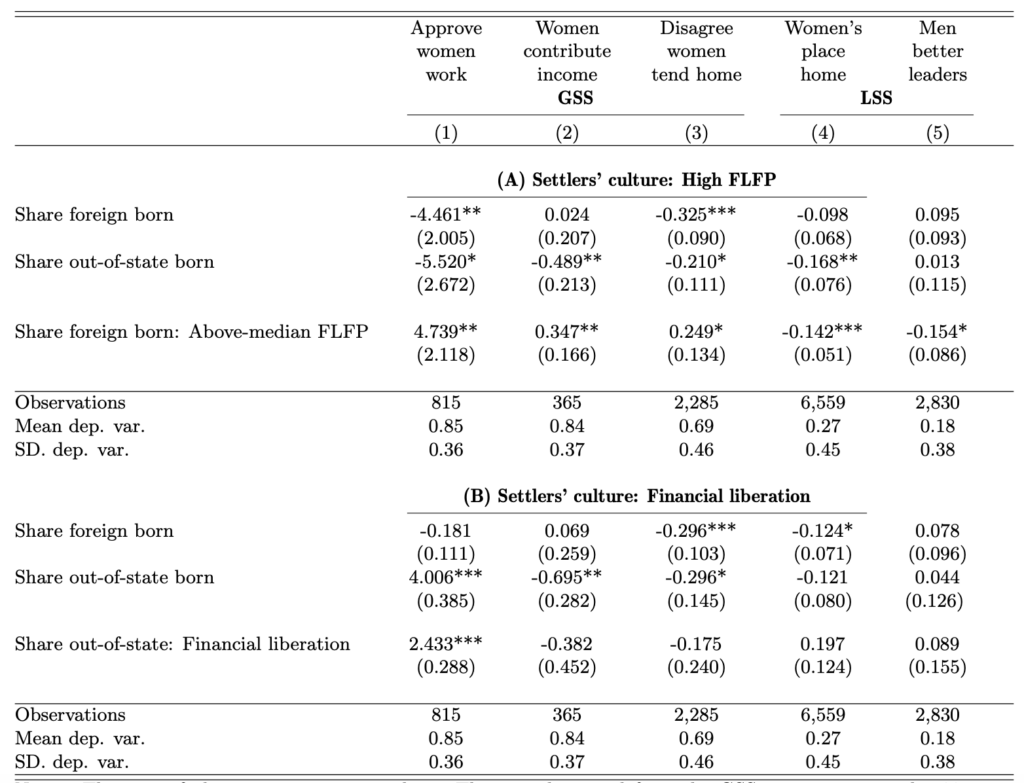

I then examine whether individuals currently residing in US counties that historically hosted a higher proportion of settlers with progressive gender attitudes exhibit pro-women’s empowerment and achievement attitudes beyond domestic responsibilities. To do this, I analyze data from the General Social Survey (GSS) and the LifeStyle Survey (LSS) and find that residents in counties with greater shares of early settlers from places characterized by high FLFP and women’s financial rights are more likely to support women’s participation in work and national affairs, not limited to household duties. These findings indicate the persistence of progressive gender attitudes in these counties.

This paper contributes to four strands of the literature. First, I contribute to the literature on the roots and persistence of cultural traits, specifically gender norms (Alesina et al. 2013; Algan and Cahuc 2006; Baranov et al. 2023; Becker and Woessmann 2008; Campa and Serafinelli 2019; Cortés et al. 2022; Gay 2023; Grosjean and Khattar 2019; Hansen et al. 2015; Nunn 2014; Teso 2019). Natural experiments in history affecting sex ratios, historical agricultural practices, and historical institutions including religion and family structures are documented as crucial determinants affecting the formation of gender norms. I contribute to this literature by examining a novel factor that may explain variations in gender norms across societies, focusing on the effects of early settlers’ characteristics. I show that their cultural traits at early stages of institutional and cultural formation have lasting impacts on the prevailing culture. These settlers thus leave the largest imprint on a locale’s gender norms by shaping its future formal and informal institutions, to which later migrants assimilate. The relatively underdeveloped cultural and institutional environment in these newly established counties allowed settlers to substantially impact the formation of local culture, institutions, and social identity.

Examining newly formed counties at various stages of cultural and institutional development presents a novel approach to directly assess the influence of early settlers and offers a potential mechanism for understanding persistence in terms of their impact on shaping local institutions and fostering entrenched local gender-liberal attitudes. Baranov et al. (2023) show that variation in the sex ratio of early settlers in Australia had persistent effects on gender norms. Baranov et al. (2020) examine whether the convict makeup of initial settlers in Australia had long-term effects on culture and show a persistent influence of convict colonization on marriage-related social norms. Brodeur et al. (2020) document that while common-law-based legal institutions improve women’s socioeconomic outcomes, these gains are absent or dampened in societies where ancestral cultural norms limit their rights. Other particularly relevant studies are Bazzi et al. (2020) and Grosjean (2014). Bazzi et al. (2020) revisit Turner’s thesis (Turner 1893), which argues that the American frontier fostered individualism in the United States, and document a more pervasive individualism and a greater opposition to redistribution in US counties with a greater frontier experience. Following an influential work in social psychology (Cohen et al. 1996), Grosjean (2014) addresses the cultural effects (the culture of honor) of the type of settler population (herders) in the South.

Second, this paper contributes to the literature on immigrants and their assimilation and gender norms (Alesina and Giuliano 2010; Antecol 2000; Blau 1992; Blau et al. 2011; Blau 2015; Blau et al. 2020; Fernandez et al. 2004; Fernandez and Fogli 2009; Fortin 2005). A strand of literature examining culture and gender norms relies on an epidemiological approach, which aims at separating the impacts of culture from those of institutions and economic environments. This approach relies on the descendants of immigrants, arguing that the latter transmit the values and beliefs of their country of origin in an institutional environment that is the same across all different immigrant groups (Fernandez 2011). This paper considers the first iteration of immigrants, who themselves played an important role in shaping the institutional environment that previous studies, relying on epidemiological approaches, treat as constant when examining subsequent immigrants.

Third, this paper contributes to the existing literature that documents (theoretically and empirically) the importance of initial conditions in determining the long-run equilibrium and modes of transmission (Akerlof and Kranton 2000; Bisin and Verdier 2011; Gay 2023; Shayo 2009), and to the emerging quantitative research that shows immigrants and culture matters for economic outcomes (Ager and Brückner 2013; Algan and Cahuc 2006; Barro and McCleary 2003; Fernandez and Fogli 2009; Guiso et al. 2009; Giuliano 2007; Sequeira et al. 2020; Tabellini 2010).1See Nunn and Puga (2012) for a comprehensive review of these studies. Fulford et al. (2020) examine the short- and long-term impact of immigrants and their descendants on local development in US counties. Exploring variations in country-of-ancestry composition, Fulford et al. (2020) show that immigrants from countries with higher economic development, cultural traits that favor cooperation, and a long history of a centralized state have a greater positive impact on county GDP per worker. Although much of the literature has focused on natural resource endowments, the cultural background of early settlers can be, and has been, interpreted as an endowment. My results provide evidence supporting both the horizontal and vertical transmission of gender norms. Miho et al. (2023) document evidence of between-group horizontal cultural transmission of gender norms using Stalin’s ethnic deportations as a historical experiment.

This paper also contributes to the growing literature on how patterns of migration shape cultural differences. In particular, it offers a framework for documenting that when immigration coincides with the critical juncture phase of institutional development in destination locations, it can help to propagate and entrench norms carried by immigrants in newly established locations (Brodeur et al. 2020; Brodeur and Haddad 2021; Couttenier et al. 2017; Grosjean 2014). I thus contribute to the literature on the origins of cultural differences and the effects of migration in shaping the evolution of cultures across societies. Finally, this paper sets the stage for future research to examine a host of other cultural traits in settler populations as well as other settler societies.

Several papers, including Bazzi et al. (2020), Grosjean (2014), Grosjean and Khattar (2019), and Baranov et al. (2023), show that initial cultural conditions matter. In addition, many papers since Fernandez and Fogli (2009) (including Blau et al. 2011 and Blau 2015) show that the culture of migrants persists, including in the case of FLFP. There are also other existing studies that have documented that the inflow of individuals with different cultural or political preferences shapes the values of receiving counties in the United States (e.g., Bazzi et al. 2021; Giuliano and Nunn 2021). This plausibly provides an answer to the question of whether we should expect a new culture to emerge in host societies. However, this research provides a novel framework to empirically examine the cultural legacy of first effective settlement and investigate cultural formation in settler societies.

The study supports previous findings of the literature on cultural persistence, namely several studies of the United States and other settlers’ countries, which document a lasting imprint of the characteristics and circumstances of early settlements on subsequent socioeconomic development. While there is an extensive literature on the roots of cultural traits, the novelty of this study in comparison to a battery of recent works (e.g., Bazzi et al. 2020; Fernandez 2011; Fiszbein et al. 2022; Guiso et al. 2016; Knudsen 2019; Nunn and Wantchekon 2011; Schulz et al. 2019; Spolaore and Wacziarg 2013; Voigtl¨ander and Voth 2012) is the significance of “first” settlement. Contrary to other persistence studies examining historical determinants at some historical point, this paper emphasizes the greater importance of initial settlement than later settlement. Its most notable contribution is to provide an “experiment” and a framework showing that early settlers can have an outsized influence on local norms when settlement coincides with early stages of cultural and institutional development. Unlike previous papers that uniquely consider immigrants from abroad (particularly European immigrants) to the United States, uniquely focus on movers within the United States (e.g., Southern migration), or solely consider frontier settlers, this paper examines the impact of both foreign (including European immigrants) and out-of-state born settlers on culture in all newly established US counties, which is also more comprehensive than solely considering frontier settlers.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, I provide a brief historical background on the process of county creation in the United States and a conceptual framework. In Section 3, I describe the novel methodology that allows me to investigate the cultural legacy of first settlement and the data sources used in this framework. I also provide some detailed descriptive statistics. Section 4 outlines the empirical strategy, and Section 5 discusses the results and presents several robustness checks. Section 6 addresses additional concerns, and Section 7 concludes.

2 Historical and Conceptual Background

In this section, I first provide a brief overview of the process of territorial expansion in the United States as well as state incorporation and county creation. County creation events provide an adequate setting to focus on counties at early stages of community, societal, cultural, and institutional development. In Appendix Section 7.1, I discuss alternative ways to define and measure newly settled areas based on population and population density thresholds. In the rest of this section, I provide a conceptual framework offering insights on the implications of Zelinsky (1973)’s doctrine of first effective settlement.

2.1 Territorial Expansion, State Incorporation, and County Creation

On July 4, 1776, the United States was created out of the Thirteen Colonies,2The Thirteen Colonies became New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. which declared their independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain and proclaimed themselves as free and independent states. It was not until 1873 with the Treaty of Paris, which put an end to the American Revolutionary War, that their independence was recognized by Great Britain.

The United States evolved from the Thirteen Colonies to its current form as a result of the following five largest territorial expansion events.3Appendix Figure A1 displays these expansion events. The first was the Louisiana Purchase (1803), which was a massive land purchase constituting almost 25 percent of the present-day United States, covering land from New Orleans up to Montana and North Dakota. The Adams-Onis Treaty, or the Florida Purchase Treaty, (1819) put an end to lengthy negotiations between the United States and Spain, officially transferring Florida to the United States. The third largest territorial expansion was the Texas Annexation (1845), which involved annexing the Republic of Texas—a region that had declared its independence from Mexico—and its subsequent admission to the Union as a US state. In 1848, the Mexican Cession encompassed the region that Mexico ceded to the United States as a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo after the Mexican-American war. Finally, the Alaska Purchase in 1867 resulted in the acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire by the United States.

The Congress of the Confederation, known as the United States in Congress Assembled, had governing authority over the United States. Its authority was granted by the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, which was the first constitution of the United States (an agreement among the 13 original states). The Congress of the Confederation enacted two key ordinances: the Land Ordinance of 1784 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. These two ordinances organized the creation of territorial governance and dictated the protocols for state admission to the Union, the division of land into administrative units, and public use of land. The Land Ordinance was a standardized system for settling and selling land, allowing frontier migrants moving westward to acquire land through direct sales from the federal government via the Public Lands Survey System of grids of square townships for the distribution and sale of land in definable parcels as a commodity. The Northwest Ordinance created the Northwest territory, the first organized incorporated territory of the United States beyond the 13 original colonies.

The westward territorial expansion of the United States happened gradually and was largely driven by population pressures and external geopolitical forces (Davis et al. 1972). However, it did not occur peacefully. With the arrival of more explorers, and as new settlers moved in, Native American tribes, previously occupying the West, were displaced and lands were violently taken away from them. Treaties forced millions of Native Americans onto reservations, which were then frequently broken, leading to even larger shares of lands being acquired by settlers.

US territories were administrative divisions overseen by the US government, but they were not sovereign entities like US states. They included both organized incorporated territories, governed through an organic act and constituting integral parts of the United States (where full constitutional rights were applicable), and unincorporated territories, which were not considered integral parts of the United States (with only partial application of the Constitution). The process of incorporation was under the authority of the US Congress. The Admission to the Union Clause of the US Constitution (preceded by the two ordinances) dictated how these territories would be admitted to the Union as US states. A total of 31 out of 37 states admitted to the Union by Congress were established within US-organized, incorporated territories. Sometimes an entire US territory became a state and sometimes just part of it.

The Northwest Ordinance authorized the creation of counties by the governor’s proclamation until the organization of the territorial general assembly, and thereafter by the general assembly itself. US counties constituted administrative or political subdivisions of a state. In an organized incorporated territory (not yet granted statehood), the territorial legislative assembly had the authority to create counties. For example, Arizona territory established by the Arizona Organic Act enacted the creation of Arizona’s first four counties (Mohave, Pima, Yavapai, and Yuma). Thus, US counties were, in some cases, formed before statehood.4 Appendix Figure A2 displays the territorial act in 1818 that was enacted by the territorial legislature of Alabama, which established Marengo County. In US states (organized incorporated territory admitted to the Union or US states not established within US-organized incorporated territories), county creation was under the authority of the state-specific General Assembly of Senate and House of Representatives, and conditions for county creation were dictated by state constitutions.5 For instance, Texas’s state constitution dictated that “no existing county could be reduced to less than 900 square miles without the consent of a two-thirds majority of the Legislature. In addition, the Legislature could continue to create counties without consent of the residents living on the land area being considered.” Other conditions imposed that new counties that were to be formed in Texas state from unorganized lands must be at least 900 square miles. Appendix Figure A3 displays an act passed by Alabama state to establish a new county as a subdivision of previously formed counties.

2.2 Conceptual Background

Wilbur Zelinsky is an American cultural geographer with many geographical studies on American popular culture. He famously argued in one of his books (Zelinsky 1973) that the first settlers significantly impact the dominant culture of a given nation. His doctrine of first effective settlement (also known as the Zelinsky 1973 doctrine) is a theory in cultural geography that served as a basis for future theories linking American history to present-day events. Zelinsky’s view—on how and why the behavior of the initial group of colonizers (settlers) matters more than that of subsequent immigrants in shaping the cultural geography of a given place—is based on the idea that the cultural institutions established by the first settlers will remain ingrained in the social fabric of a given territory. Moreover, the newly established institutions are self-perpetuating in the sense that they reproduce their cultures across time. Later immigrants will not defy prevailing institutions but rather will assimilate and socialize into the territory’s cultures and views. While changes will continue to occur in settled regions, these will be anchored in the cultural institutions established by the initial settlers. A related theory is the “fragment theory” of class, culture, and ideology by Louis Hartz in his influential book The Founding of New Societies (Hartz 1969), which argues that the diverse political and cultural traditions in new societies (in the United States, Latin America, South Africa, Canada, and Australia) represent a cultural fragment of the European countries from which they originated. He posited that each new society retains the ideology that was dominant in its parent country at the time of its founding.6Another related point is by Frederick Jackson Turner, who argued that the American frontier fostered individualism (Turner 1893). The earliest stages of development on the frontier were likely a critical juncture in the formation of local culture, as alluded by Turner (1893)’s thesis, where he notes that the “traits [of frontier society] have, while softening down, still persisted as survivals in the place of their origin, even when a higher social organization succeeded.”

Woodard (2011) expanded the doctrine of first effective settlement, particularly the homogeneity within settled nations, and argued that the movement of people to new territories, bringing with them the culture of the society they came from, resulted in the creation of multiple nations, which together constitute the country. These multiple American nations are thus culturally segmented parts, each composed of a group of people who share a common culture and origin defined beyond legal states and international boundaries. Woodard’s argument, inspired by the first effective settlement doctrine, relates directly to cultural formation in settler societies.

The implications of the various doctrines and theories from adjacent disciplines discussed above suggest that the culture of settlers of newly created US counties has a lasting impact on the culture formed in these areas. As counties are newly formed, and given that settlement is at its early stages,

settlers who first inhabit these territories may influence the formation of local economic, social, political, and cultural institutions—both formal and informal—institutions in a way that shapes the social fabric of that given county.

The purpose of this paper is thus to empirically examine the implications of these theories, particularly Zelinsky (1973)’s doctrine. It tests whether migrants who moved to US counties during their early formation carried the values and beliefs from their societies of origin to their new locales, and how these influenced the formation of institutions and culture in these newly settled areas. This relates to cultural persistence via both the spatial (horizontal/cultural continuity via portability) and the vertical (across generations or over time) transmission of cultural beliefs.

One possible outcome is that these settlers carried their cultural beliefs from their home country/state, moved to US counties, and shaped a culture that mirrors their home country/state culture, which persists to the present day. This would validate both the horizontal and vertical aspects of transmission of norms and values in newly formed US counties. Another possible outcome is that they moved to US counties and shaped a culture mirroring that of their home country or state, but this cultural influence did not persist over time or across generations. This would thus validate the horizontal transmission of norms and values only. Last, settlers may have arrived to US counties and shaped a culture that does not mirror that of their home country or state, meaning that both horizontal and vertical transmissions of cultural beliefs are absent in newly formed counties.

3 Data

In this section, I describe the novel methodology used to investigate the cultural legacy of first settlement, particularly how to capture counties in their early stages of cultural and institutional development, construct settlers’ population, and examine their composition in terms of demographic and cultural characteristics. I also describe the data sources used in this framework and provide some detailed descriptive statistics.

3.1 US Counties

I focus on county creation events to capture counties at their early stages of cultural and institutional development. I disregard counties created before 1840 and after 1940, limiting my analysis to counties formed between 1840 and 1940, for several reasons. First, the time period falls within the era of mass migration, which provides an adequate setting for both across- and within-state variation in settler composition as a result of the diverse and heavy migrant inflows to the United States during that period. Second, given that full-count US censuses are available only between 1850 and 1940, and counties are not identified in public-use microdata from 1950 onward, I cannot examine the composition of settlers residing in newly formed US counties any time before or after that period. Additionally, data on FLFP, the main outcome of interest in this paper, are only available as of 1850, which explains disregarding US counties created before 1840.7Out of 3,172 US counties, almost 42 percent were created before 1840, and only 2 percent were created after 1940. The remaining counties were created sometime between 1840 and 1940. As mentioned earlier, counties created between 1880 and 1889 are excluded from the analysis given that census data are missing for 1890 from all sources. Additionally, few counties that do not classify as new nor partitioned are also excluded. Expanding the sample selection to include the 65 counties created post-1940 does not alter the main sample of new counties given that none of them were created from noncounty areas. Appendix Section 7.1 and Appendix Figure A4 provide a detailed discussion on the importance of using county creation events to capture the first effective settlement rather than using population and population density thresholds.

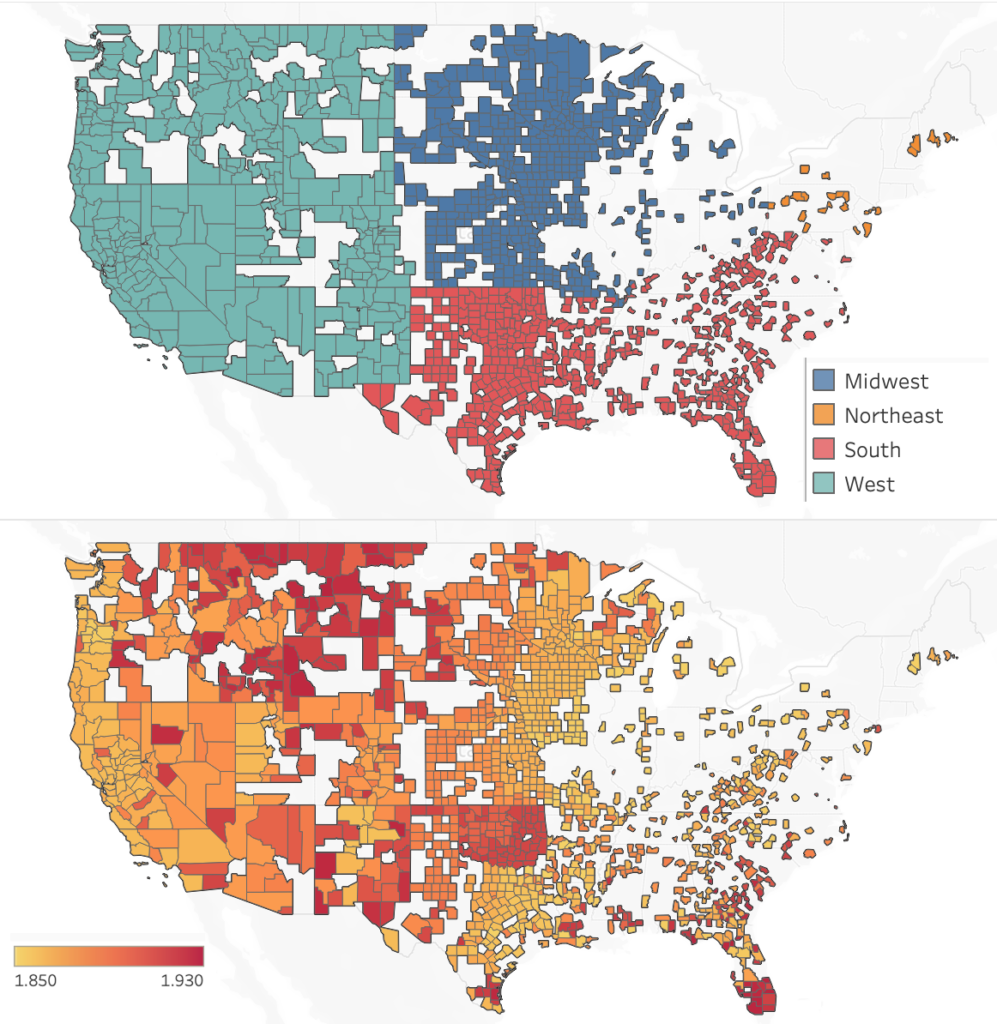

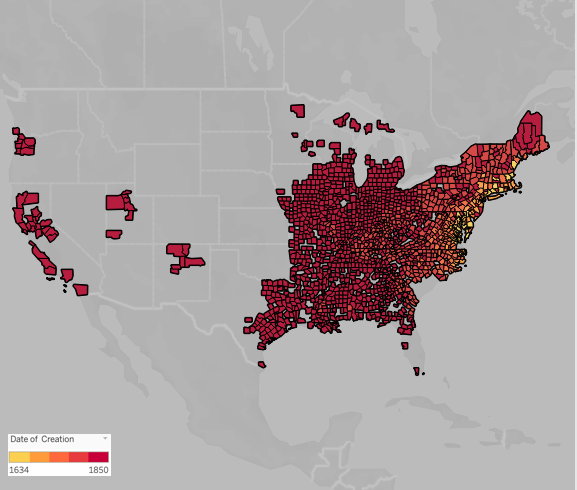

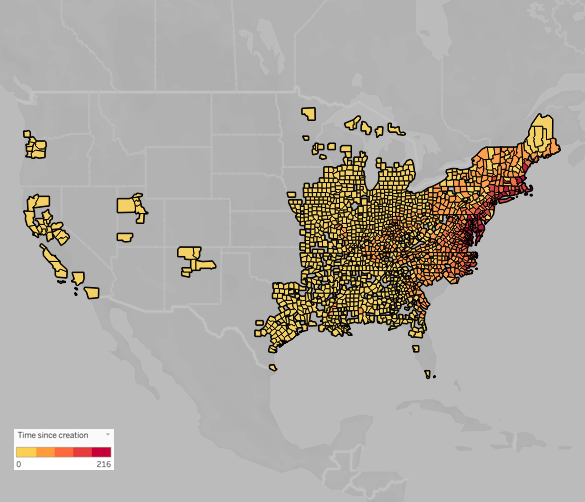

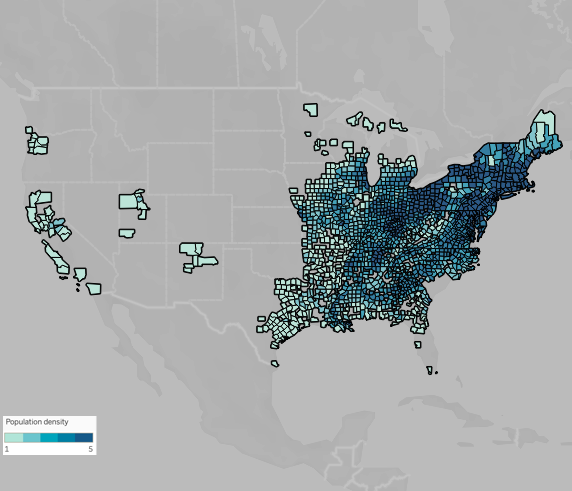

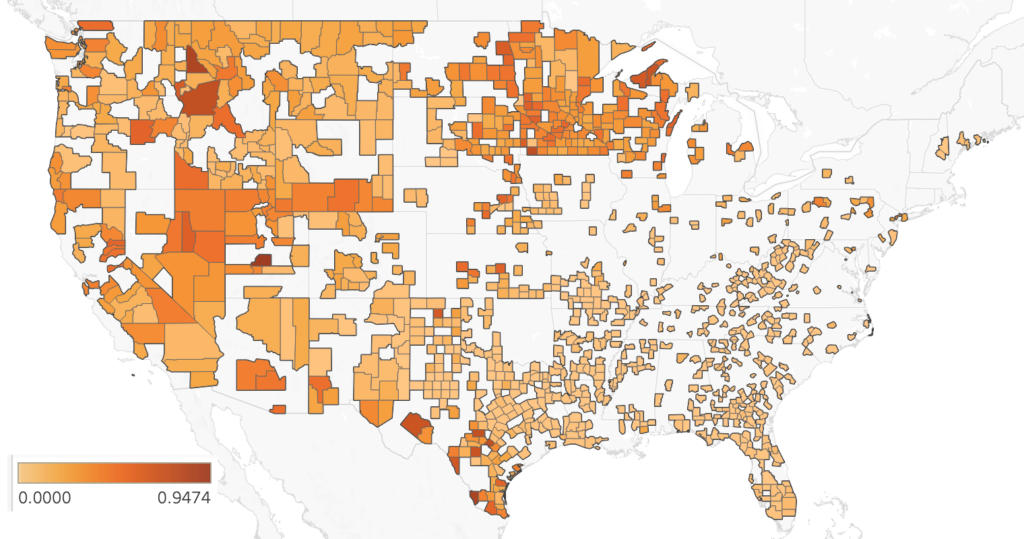

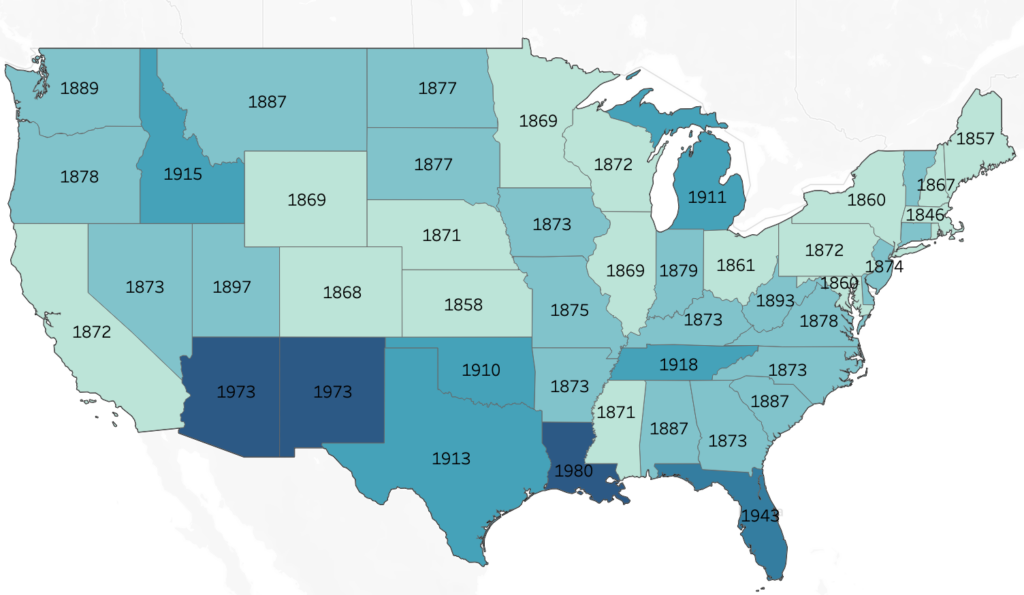

To construct my sample of US counties created between 1840 and 1940, I rely on the Atlas of Historical County Boundaries data set.8Data are available from https://publications.newberry.org/ahcbp. This data set provides information about the creation of every US county as well as their changes in administrative status, size (land area in square miles), shape, and location. I end up with a total of 1,381 US counties created between 1840 and 1940 (see Figure I). About 77 percent of these counties were created before 1900, and about 58 percent are in the West and Midwest census regions, 41 percent in the South census region, and the remaining counties in the Northeast census region. Due to missing census data for 1890 from all sources, I exclude 167 counties created between 1880 and 1889 from the sample.

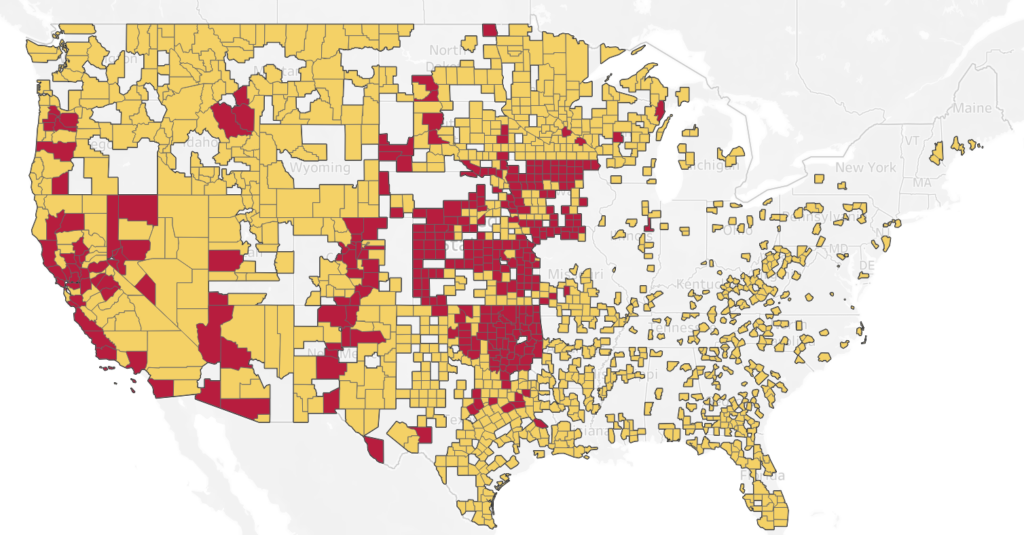

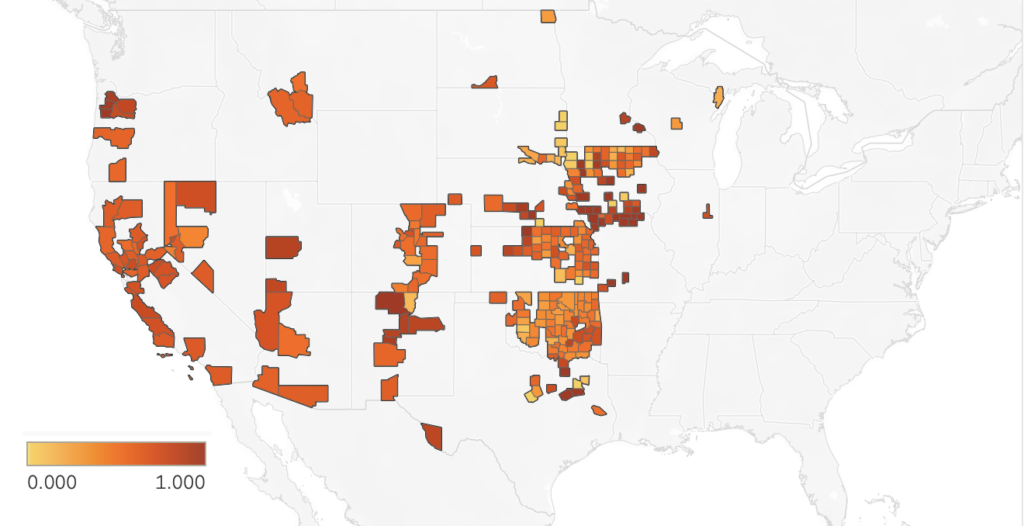

The 1,381 US counties created between 1840 and 1940 include counties that were not subdivided or partitioned but were created from noncounty areas, which I refer to as new counties. Figure II displays these new US counties in red. About 55 percent are in the Midwest census region, about 22 percent in the South census region, and the remaining 23 percent in the West census region. Close to 82 percent of these counties were formed before 1900, and the remaining 18 percent were formed sometime after 1900.

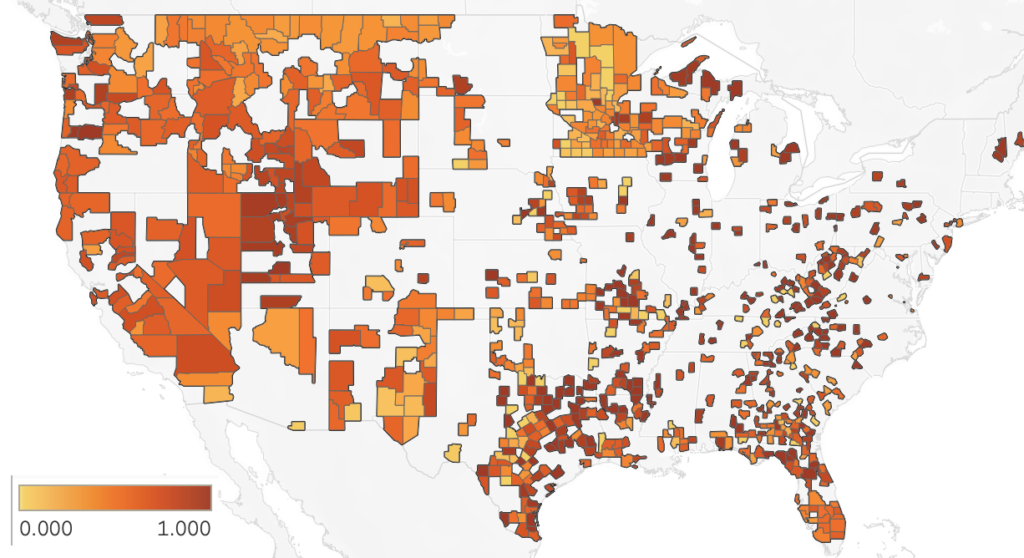

Additionally, new counties were created either by subdividing a previously formed county, by combining areas from multiple established counties, or through a combination of noncounty areas and portions of already formed counties. I refer to these as partitioned counties (see the yellow areas in Figure II). The gray areas in Figure II indicate counties that are excluded from the analysis because they were either created before 1840, between 1880 and 1889, or after 1940.

My main analysis is limited to the sample of new counties, i.e., those that were not subdivided or partitioned but were created (entirely) from noncounty areas. The main sample sums up to a total of 324 counties, excluding partitioned counties. This is crucial given that counties created through subdivision may differ from new counties in terms of how established the county, community, society, and institutions are. While the average number of inhabitants was 6,114 for new counties and 6,867 for partitioned counties, population density per square mile was more than four times larger in the latter group of counties (population density of 41.8) compared to new counties (population density of 10.9). Population and population density data are obtained from the first US Census available after the county’s creation date.

To fix ideas, consider Bullock County (Appendix Figure A3), founded in 1866 in Alabama state. Since the county was created as a combination of four previously established counties (Macon, Montgomery, Pike, and Barbour), it is a partitioned county and is thus excluded from my main sample of new counties. In Appendix Section 7.2.1, I provide a detailed discussion on the classification of newly created US counties across new and partitioned categories.

3.2 Settler Population

In this subsection, I describe how I construct the settlers’ population as well as the data sources and variables used to examine this population’s composition. I also provide a descriptive analysis offering new insights on the characteristics of settlers living in newly created US counties. I present summary statistics for my entire sample of settlers, by gender and by gender and category (foreign, out-of-state, and in-state born settlers) simultaneously.

3.2.1 Settler Population and Demographic Characteristics

I define the population of early settlers as individuals residing in US counties at the time of their territorial government’s creation. Having information about each county’s year of creation, I construct the settler population using information about county identifiers from full-count census data. Specifically, I build a data set of people living in these US counties by relying on the first full-count US Census available after the county creation date. In Section 6, I examine the validity of settlers’ definition given that census data are not available for areas before they become politically organized as an administrative entity of the United States.

I rely on complete-count US Census data (1850–1940) from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, or IPUMS (Ruggles et al. 2020).9The data are available from https://usa.ipums.org/usa/. The population counts exclude most Native Americans, who were generally not enumerated by the census before 1900. IPUMS provides access to US Census microdata and includes a wide range of information about individuals’ education/literacy, labor force and fertility status, income and occupational score, among other information. I carry out my analysis at the county level, so I generate county averages based on individual characteristics. County identifiers allow me to identify the county where the household was enumerated and, more importantly, where individuals are residing. I generate settlers’ county-level average age and gender composition as well as their marital, fertility, and literacy status.

Additionally, given that settlers coming from different places are exposed to a different set of values and beliefs, it is crucial to identify their country/state of origin. To do so, I rely on a variable available from IPUMS, which indicates the US state or foreign country where the individual was born. Using information about the birthplace allows me to divide the settler population into three different categories. The first category comprises foreign-born individuals, i.e., those born outside the United States. The second category includes those born out of state, i.e., born in a different US state from where their household resided at the time the census enumerator conducted the interview. Finally, in-state born individuals are those born in the same state where their household is located.

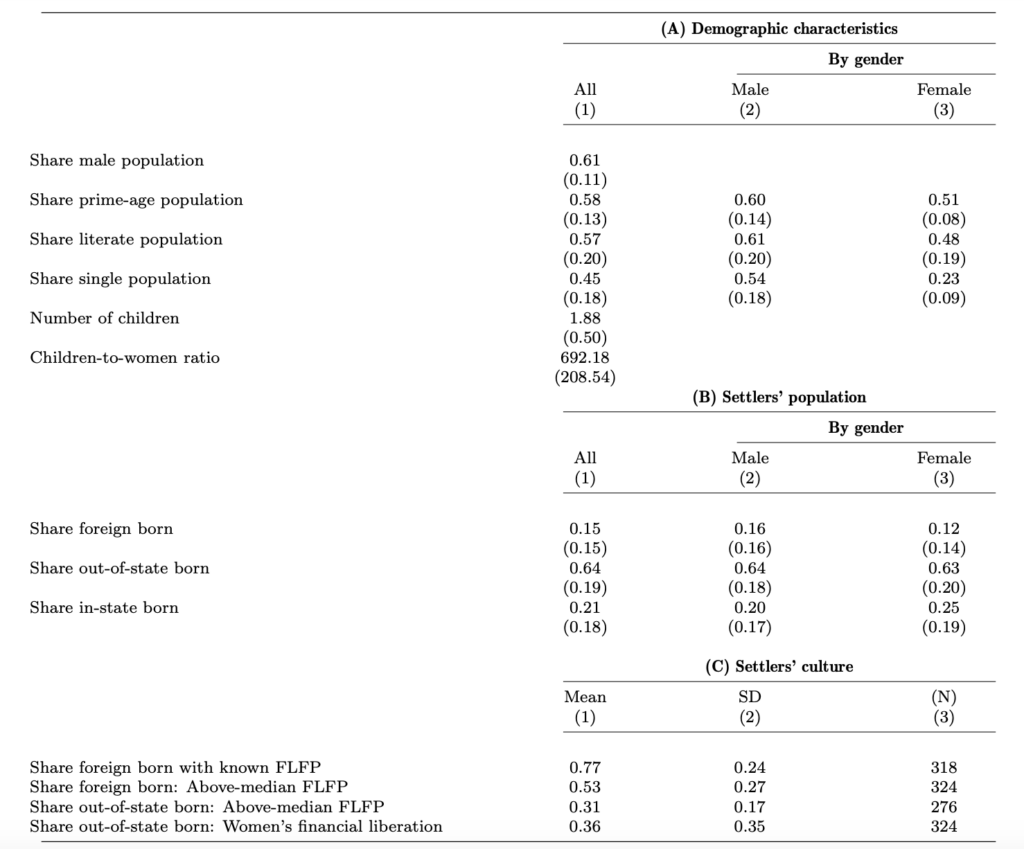

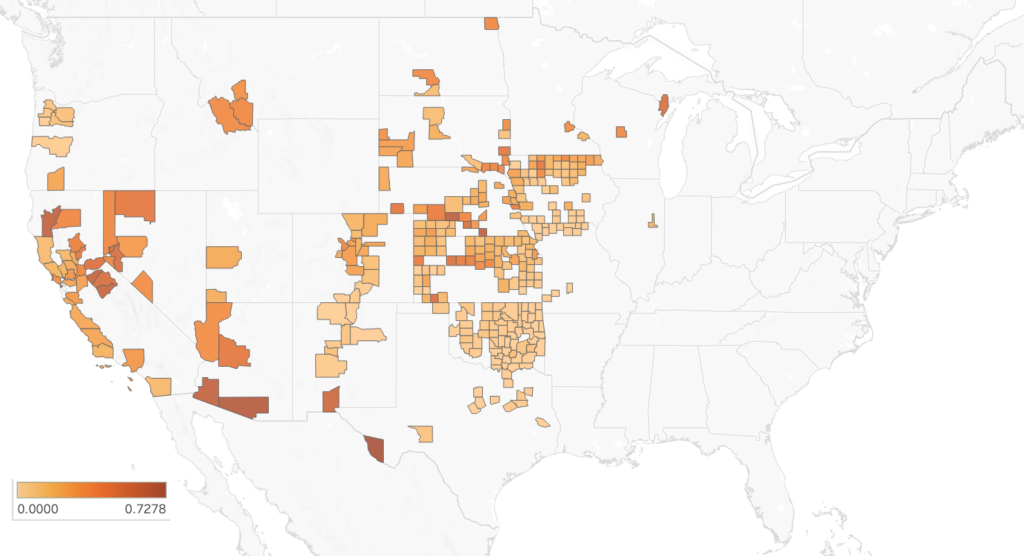

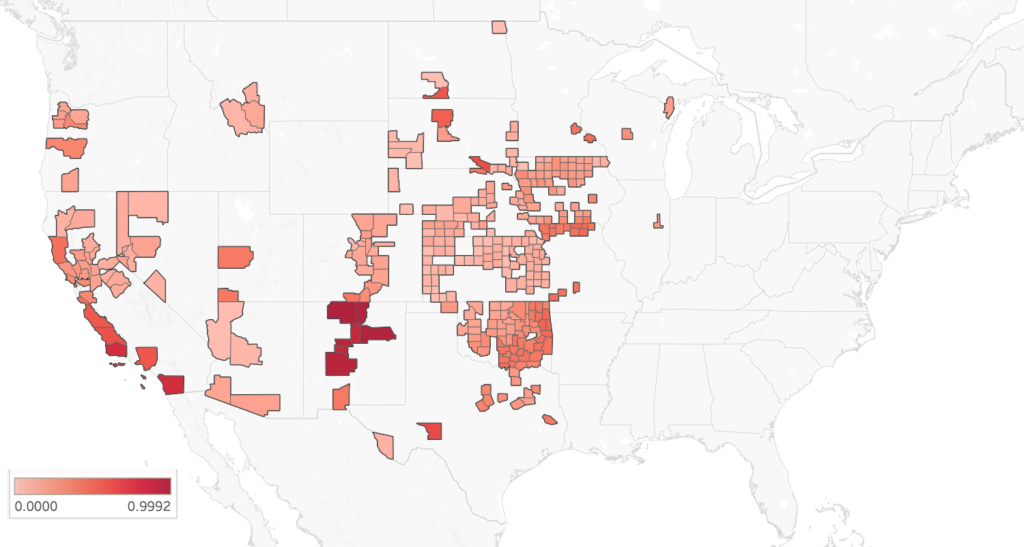

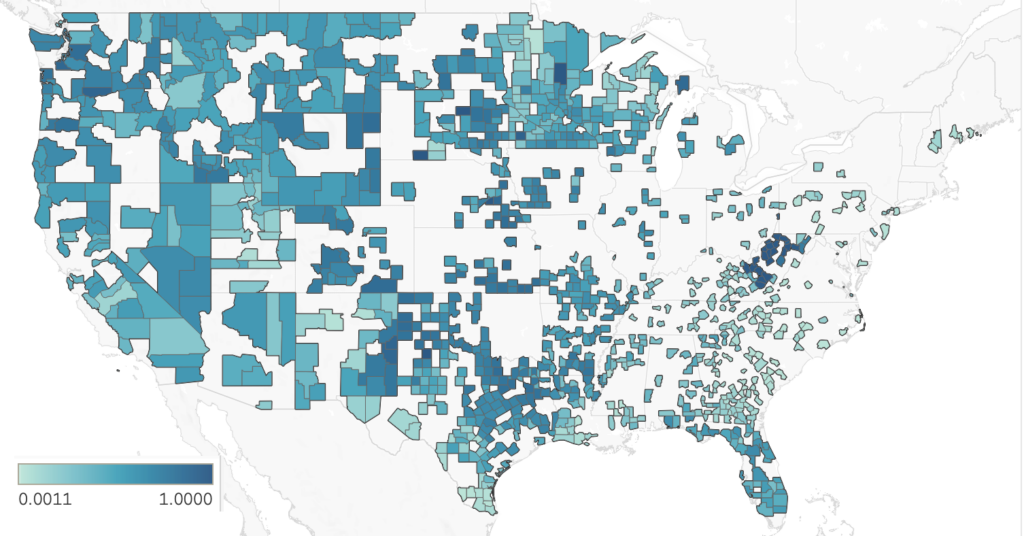

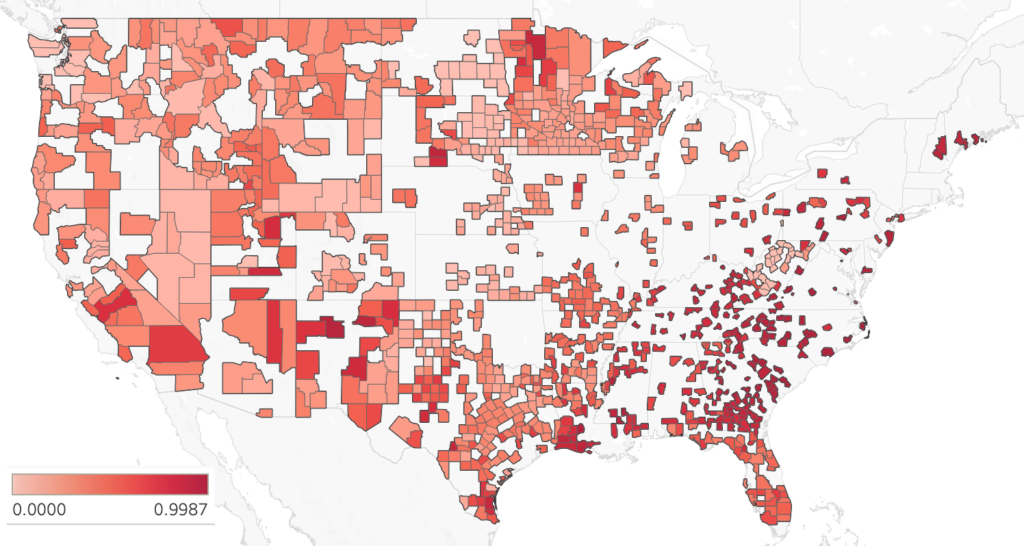

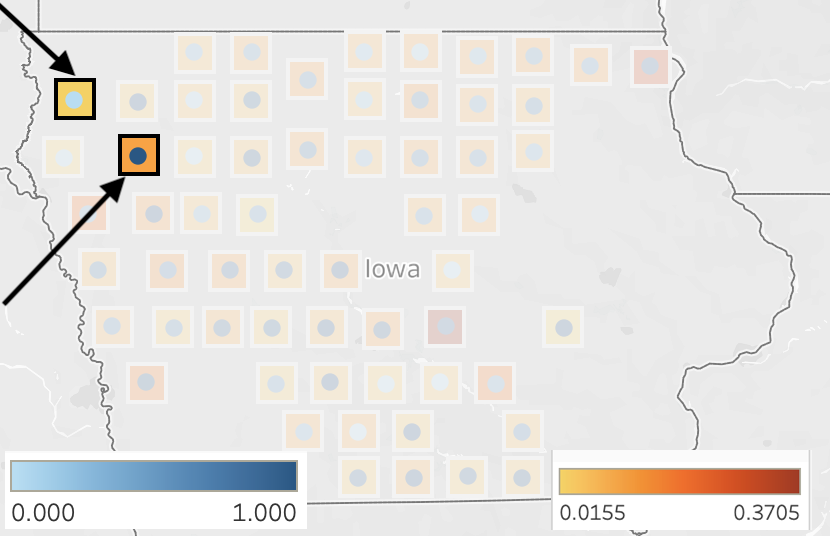

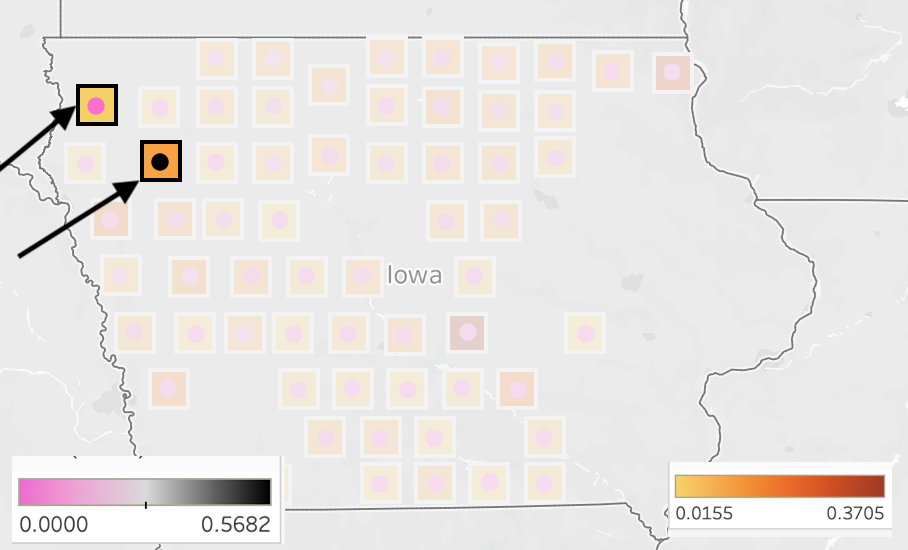

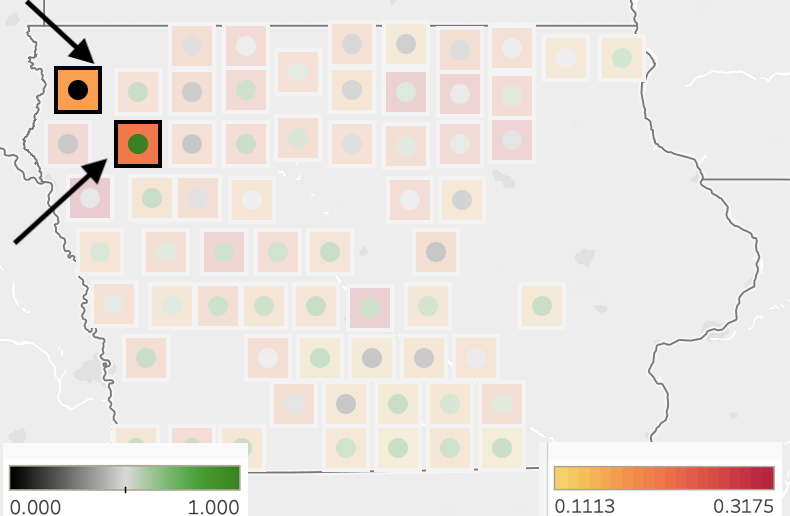

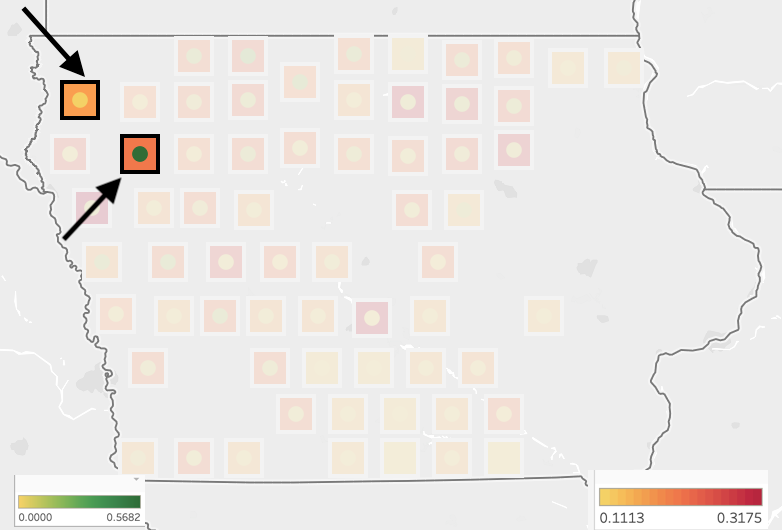

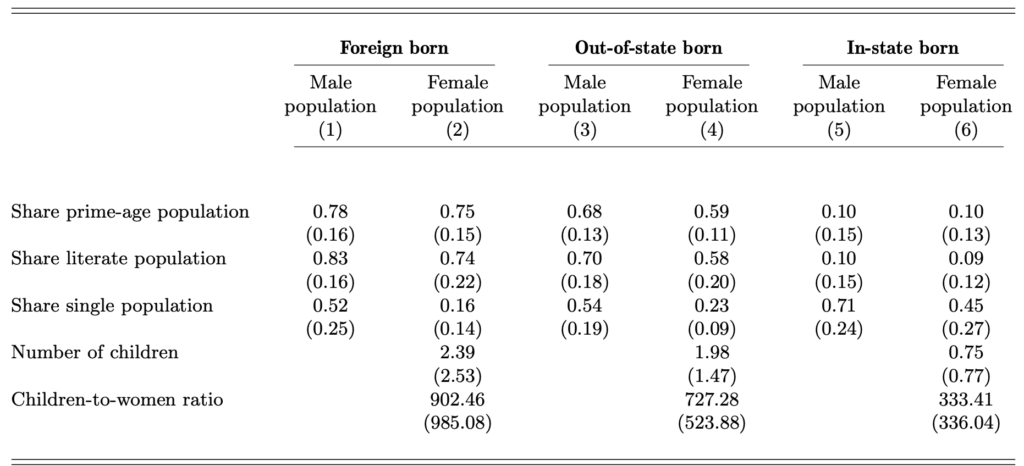

Table I provides summary statistics of the characteristics of settlers living in my sample of new US counties. Column (1), Panel (A) presents statistics for the entire sample of settlers, and columns (2) and (3) report statistics by gender. The results from column (1) show that settlers who occupied newly formed counties were mostly literate men in their prime age. The statistics reported in Panel (B) reveal that settlers were mainly out-of-state born migrants (64 percent), followed by in-state born individuals (21 percent). Foreign-born settlers constitute 15 percent of settler populations. Appendix Figure A5 illustrates the distribution of foreign-born, out-of-state, and in-state migrants out of the entire population, respectively, across my main sample of new counties. Appendix Figure A6 shows this distribution for the alternative sample of partitioned counties.

Panel (A), columns (2) and (3) of Table I show that these features apply to both male and female settlers, with a notably reduced proportion of singles among female settlers. These patterns are consistent with what historians, demographers, and economists have documented regarding the distinctive characteristics of frontier populations given the difficult and dangerous frontier conditions (Bazzi et al. 2020).

Appendix Table A1 repeats these descriptive statistics by gender for foreign, out-of-state, and in-state born settlers separately in columns (1)–(2), (3)–(4), and (5)–(6), respectively. The table confirms that regardless of gender, foreign and out-of-state born settlers were younger and more likely to be literate than in-state born individuals. Furthermore, the children-to-women ratios were significantly higher for female foreign and out-of-state-born settlers compared to those born in state.

3.2.2 Settlers’ Culture

To capture settlers’ culture, I use various proxies that reflect values and beliefs from settlers’ places of origin.10People moving to US counties from different locations may be exposed to different norms at their places of origin/birth, including gender-related ones. However, this paper does not focus on the distance traveled by these settlers. For instance, Von Berlepsch and Rodríguez-Pose (2019) exploit distance traveled and distinguish between internal migrants (what I refer to as out-of-state born individuals) and external migrants (foreign-born individuals) in their examination of the impact of migrants on counties’ long-run economic development. In contrast, I exploit migrants’ culture using gender norms at their places of origin/birth as the underlying variation rather than the distance traveled. The underlying assumption is the correspondence between settlers’ culture and the dominant culture in their sending country/state. I use a series of quantitative variables including FLFP (measured through various metrics) and women’s financial liberation rather than simply using the country or state of birth as a proxy variable for gender norms at the place of birth.11Due to data limitations, it may not be possible to explore the potential influence of different groups of Native Americans on settlers’ migration decisions or on gender norms. In some robustness specifications, I account for exposure to conflict with Native Americans. Specifically, I construct two quantitative variables. The first one captures FLFP by the country of origin per decade. The second one delves into the variation in the enactment of women’s financial rights across US sending states.12Financial empowerment is solely assessed for sending US states and not foreign countries. This is due to the heterogeneity in historical inheritance practices across various regions within a given country, as well as the scarcity of countries that granted women property and earning rights during the period of analysis.

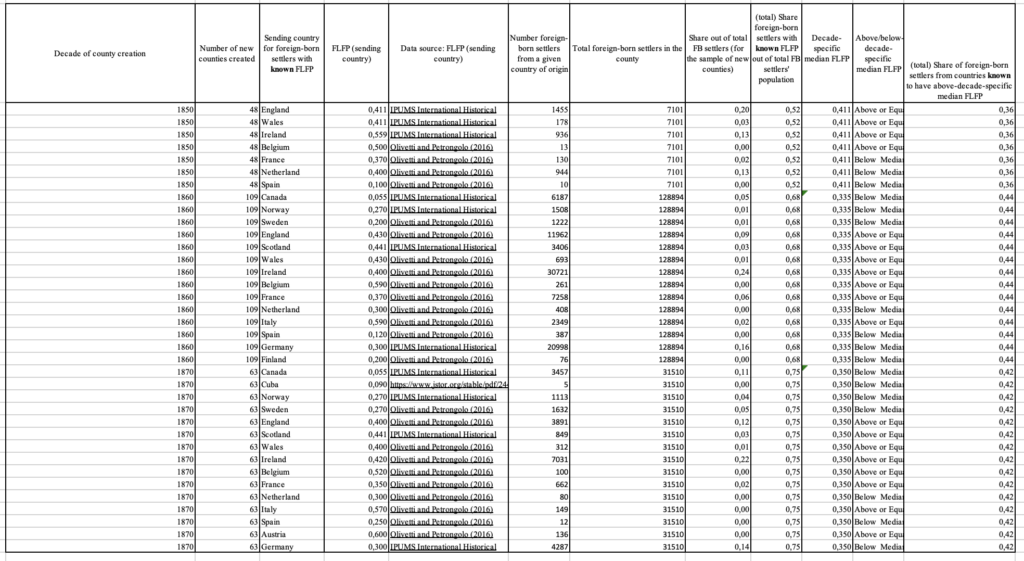

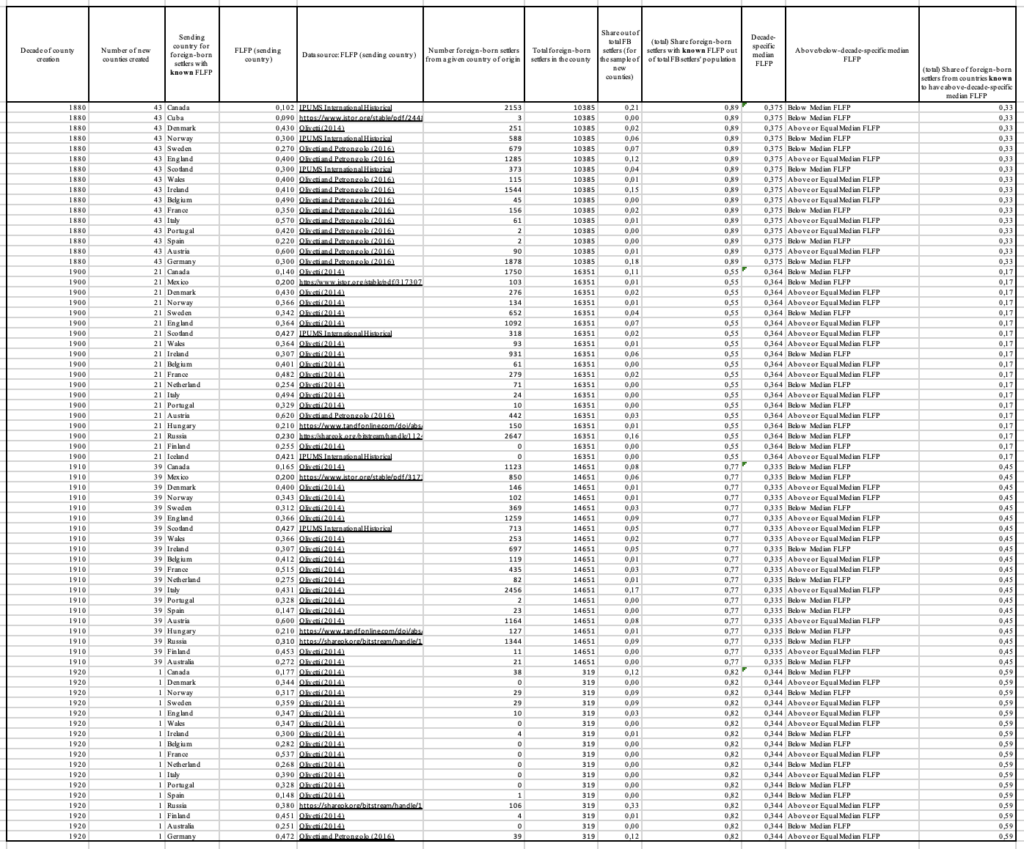

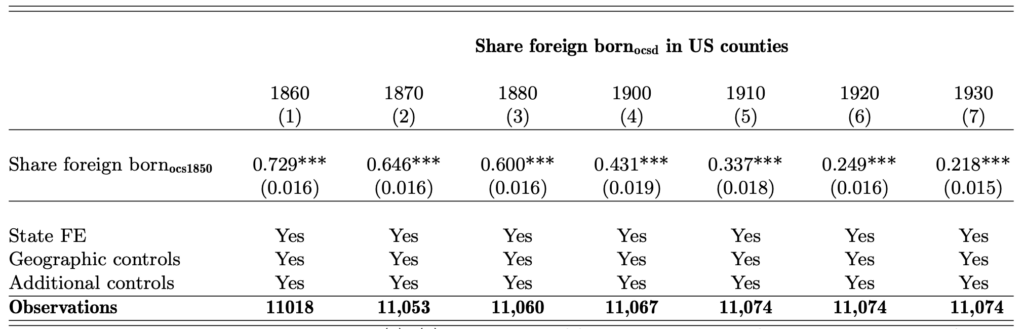

I create a data set of historical FLFP for foreign-born settlers’ sending countries (countries of birth), merging data from at least three different sources.13Foreign-born individuals from countries lacking historical labor force participation data are excluded from the population of foreign-born settlers with known FLFP. These individuals are instead classified as part of a population of foreign-born settlers with unknown FLFP. Foreign-born settlers from countries with both known and unknown FLFP comprise the entire foreign-born settler population. This includes data from IPUMS International Historical Censuses.14Data are available from https://international.ipums.org/international-action/samples. I combine this with information on FLFP by country by decade, extracted from Olivetti (2014) and Olivetti and Petrongolo (2016). Determining the optimal decade for constructing historical FLFP in the sending countries is not straightforward. In this paper, I use labor force participation data from the source countries from either the same decade, or one to two decades earlier than, the period when I identify the population of foreign-born settlers, depending on data availability. Since data on the migration date of settlers are unavailable, I gauge the characteristics of source countries based on when I observe the settlers, which is either in the same decade or a decade or two earlier, depending on data availability, before the county creation date. The underlying assumption is that the cultural beliefs of these foreign-born settlers are best reflected by the activities of their counterparts in the country of origin (Fernandez and Fogli 2009).

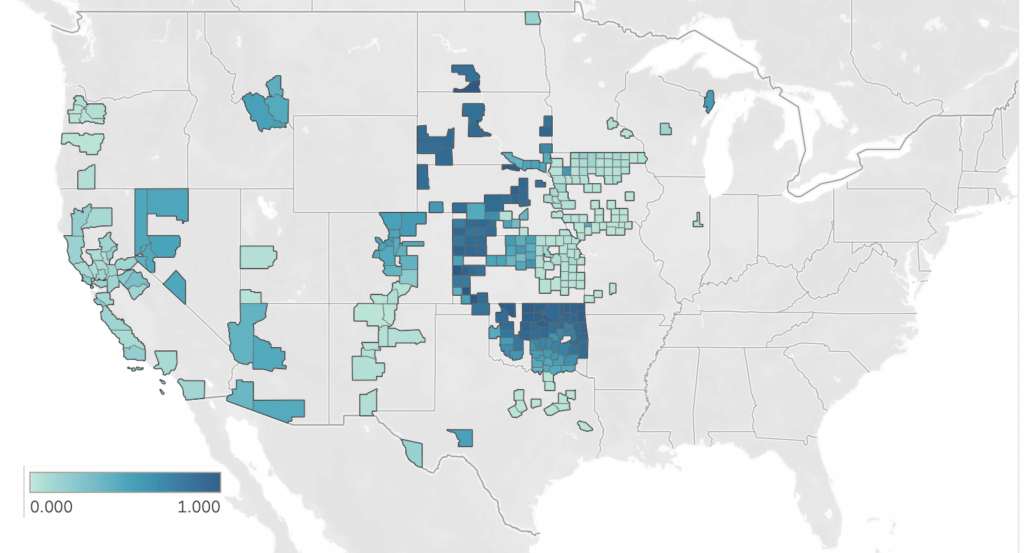

Summary statistics related to settlers’ culture reveal that foreign-born migrants primarily originated from high-FLFP countries. Table I, Panel (C) reports that 53 percent of foreign-born individuals from countries with known FLFP come from those with FLFP rates above the decade-specific median.15Notably, using the mean instead of the median does not affect the analysis. I proxy for settlers’ culture using FLFP with various metrics, not solely relying on the decade-specific median cutoff to distinguish those from high- and low-FLFP countries. I first employ a weighted average of FLFP from sending countries, adjusting for the share of foreign-born settlers residing in a specific US county and originating from a given country. I then construct a time-in-variant measure of gender norms in the origin country, established using the earliest available FLFP data for each country as of 1840. I compute most of these measures for settlers born out of state but do not incorporate them into the main specification. A more detailed discussion on this is provided later in the paper. Appendix Figure A7 shows the distribution, across my main sample of new counties, of the share of foreign-born settlers from countries known to have above-median FLFP. Appendix Figure A8 displays this distribution for the alternative sample of partitioned counties.

The second quantitative measure proxies for out-of-state born settlers’ gender norms, using the variation in the timing of passage and implementation of women’s financial liberation relative to the county creation date. This measure explores the timing of granting of property and earning rights to women across US sending states. The data on the timing of women’s financial liberation by state are obtained from Geddes and Dean (2002) and displayed in Appendix Figure A9.16Investigating the timeline of women’s legal rights (other than voting) in the 19th century, particularly during the period observed in this paper, reveals that only three countries passed formal changes and reforms regarding women’s property rights (Ireland, the United kingdom, and Scotland). I thus refrain from measuring financial liberation for settlers originating from foreign countries.

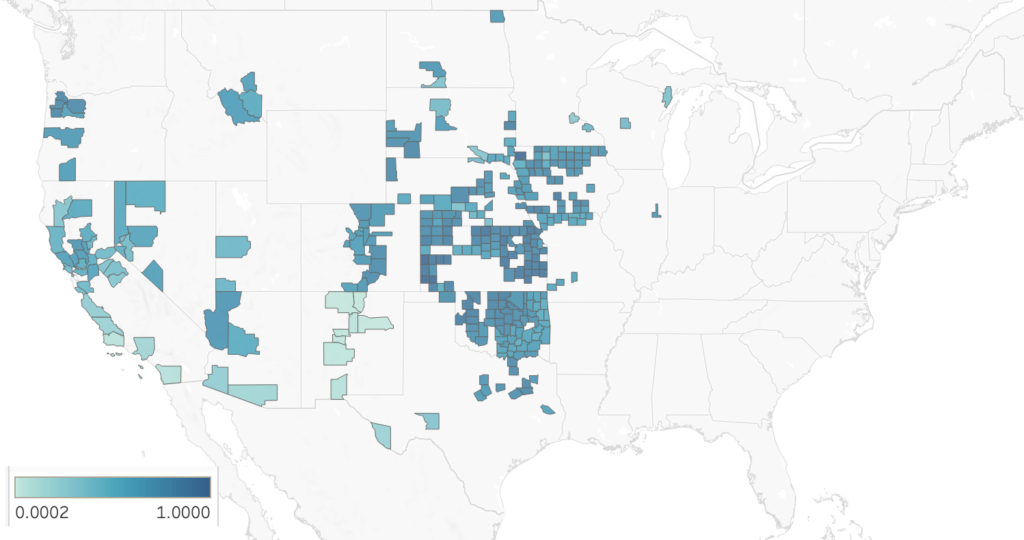

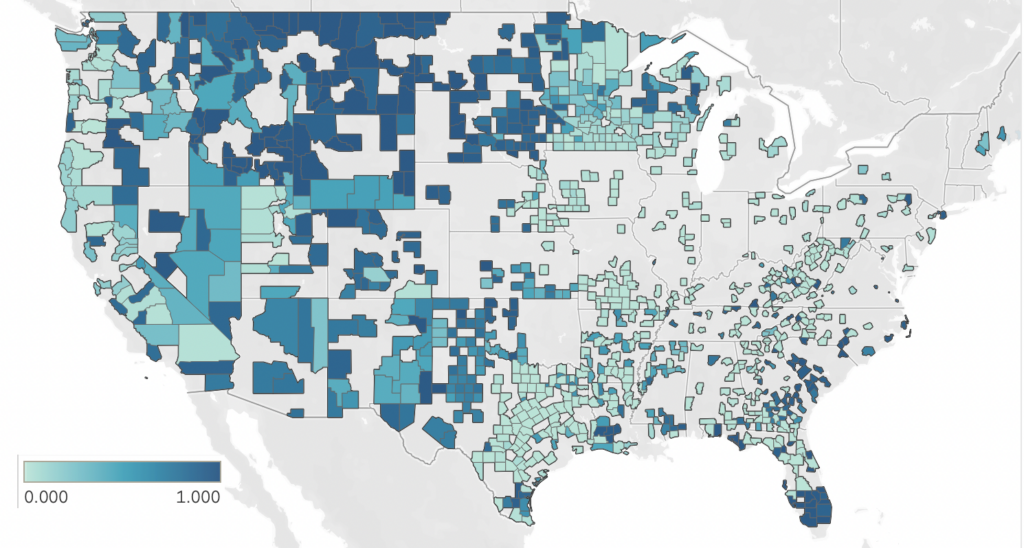

Panel (C) of Table I shows that almost 36 percent of out-of-state born settlers came from US states where women had property and earning rights (see Appendix Figure A10 for the distribution of this share across my main sample of new counties and Appendix Figure A11 for the sample of partitioned counties).

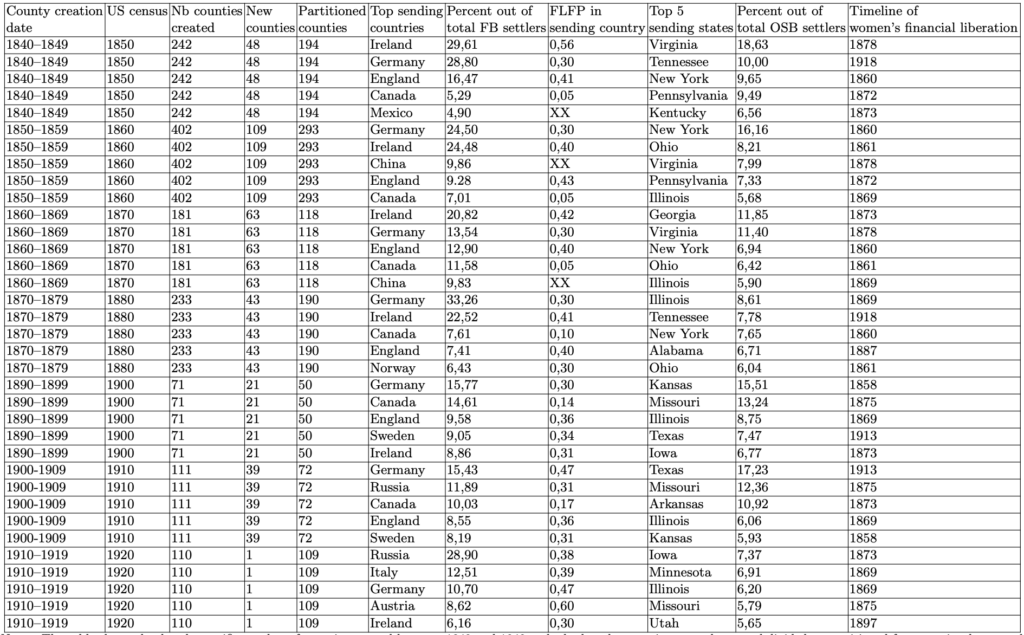

Appendix Section 7.4, particularly Appendix Figure A.8, offers a snapshot of the distribution of newly created counties by decade of creation and the type of counties established. It also includes a list of the top five sending countries/states of settlers, FLFP, and financial rights categorized by country/state of origin.

Appendix Figures A12 and A13 present a detailed overview of the countries of origin with known FLFP data, the relevant data sources used in each decade, the (total) proportion of foreign-born settlers with known FLFP out of the entire foreign-born settlers’ population, and the proportion of foreign-born settlers from countries. This information helps in understanding the sample used to establish the cutoff for high (above-median) FLFP.

3.3 FLFP in US Counties

I obtain data on FLFP in US counties from complete-count US Census data (1860–1940) from IPUMS. I rely on the variable “labforce,” which is a dichotomous variable that indicates whether a person participated in the labor force.17Official census accounts of FLFP before 1890 may be subject to underreporting. See Chiswick and Robinson (2020) for a discussion on the measurement problems of the 19th-century census FLFP. Additionally, note that before 1940, the census asked about the occupation in which individuals were “gainfully employed” (Goldin 2006).

4 Empirical Strategy

4.1 Strategy Visualization

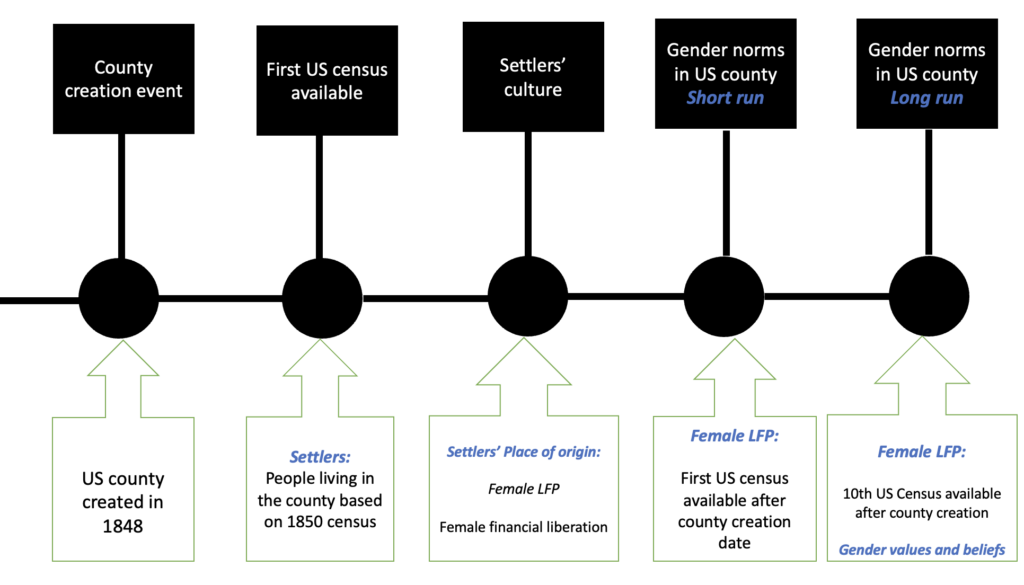

I begin by presenting a visual display to enhance the understanding of the methodology employed in this paper to investigate how the gender norms brought by early settlers can exert lasting effects on local culture. Appendix Figure A14 provides a detailed representation of the methodology used in this analysis. The primary event of interest is the county creation event. When a county is established between 1840 and 1940, I create the population of settlers using the first US Census conducted after the county’s creation date.

To assess settlers’ culture, I rely on variables such as FLFP and financial liberation in the settlers’ places of origin. To explore the role of settlers’ culture in explaining variations in gender norms within the United States, I calculate FLFP in US counties using data from the first US Census conducted after the county’s creation date for the short-run analysis. For the analysis focusing on persistence, I calculate FLFP approximately 100 years after the county’s creation date. Additionally, I measure gender values and attitudes using data from the GSS and the LSS.

4.2 Identification Strategy

In this subsection, I provide a formal description of my identification strategy and discuss potential threats to causal identification. The aim is to examine how settlers’ culture contributes to explaining variations in gender norms within the United States. The identification strategy entails a comparison of US counties created simultaneously within the same state, differing in the proportion of hosted settlers originating from regions with liberal gender attitudes. This comparison is made while considering the county-level total population and using proxies for local conditions. The analysis is conducted at the county level, focusing on my primary sample of new US counties created between 1840 and 1940. These are counties that were not subdivided or partitioned but were entirely established from noncounty areas.

In an alternative examination, I extend this analysis to the sample of partitioned counties. The rationale for considering this latter group of newly created counties is to directly test Zelinsky (1973)’s doctrine, which argues that early settlers exert an outsized influence through their imprint in shaping local culture and institutions. This approach also serves as an experiment to document one way in which persistence might have occurred, especially considering that counties formed as subdivisions of previously established counties could differ from new counties in terms of their level of societal, institutional, and cultural development.

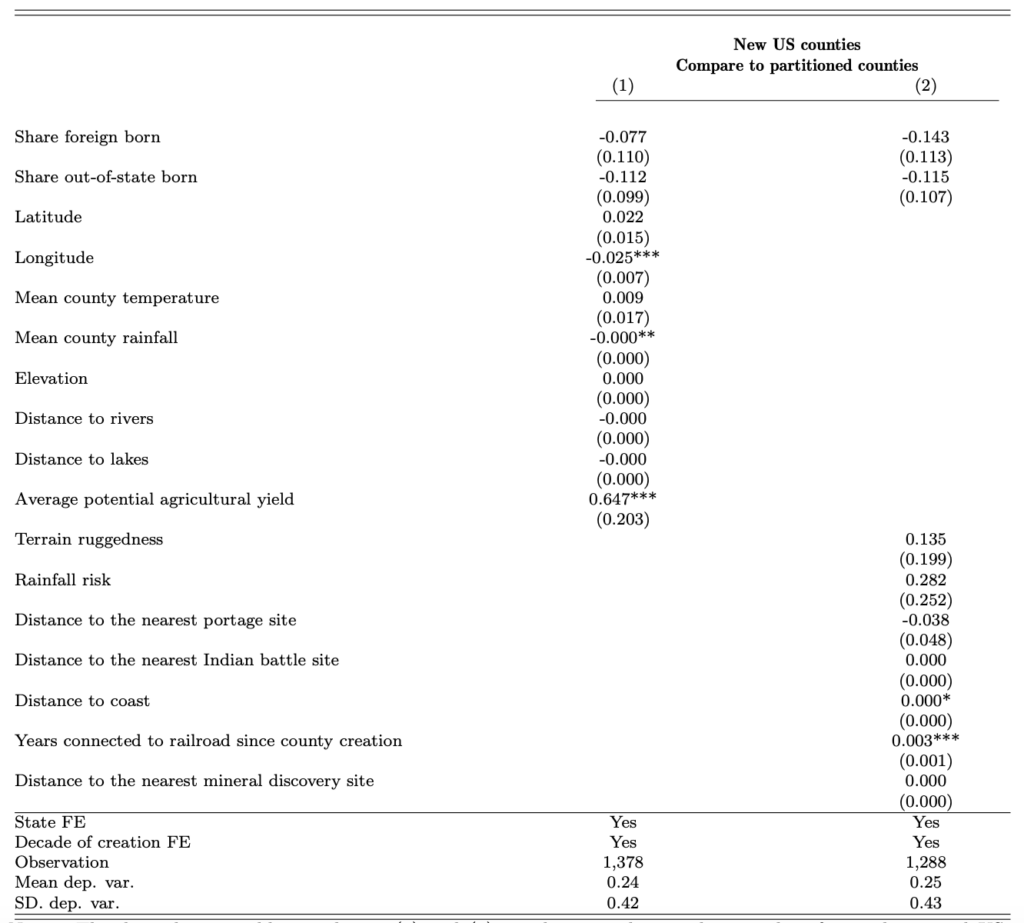

Comparing the results obtained for new counties, which are newly created from noncounty areas, with the results derived for partitioned counties, which are subdivisions of already established counties, is analogous to performing a differences-in-differences analysis.18In Appendix Table A2, I investigate whether observable county-level characteristics predict the classification of a newly created county as a new county. To do this, I focus on the sample of newly created counties and directly compare new counties with partitioned one. I present the results from linear probability models that incorporate state and decade of county creation fixed effects, along with the following geographic variables: latitude, longitude, mean county temperature, rainfall, elevation, distance to lakes and rivers from the county centroid, and average potential agricultural yield. In the second specification, I include additional controls that account for terrain ruggedness, rainfall risk, distance to the nearest portage site, distance to the nearest Indian battle site, distance to the coast, number of years the county has been intersected by railroads since its creation date, and distance to the nearest mineral discovery site. In column (1), 2 out of 10 variables are statistically significant, while in column (2), only 1 variable is significantly related to whether the county is classified as a new county. These findings suggest that the sample of new and partitioned counties is well balanced across a wide range of covariates. In the empirical analysis, I include state and decade of county creation fixed effects as well as the aforementioned geographic variables.

Although US counties were established at various times and across different states, variations across states and in the timing of county creation are not relevant for this research. The sole relevant variation lies in the composition of settlers in newly created counties, i.e., the makeup of the initial inhabitants of these counties after their creation, specifically their culture. The primary challenge for causal identification arises from omitted variables that are correlated with both the countylevel proportions of settlers from places with liberal gender attitudes and FLFP in newly created US counties. To establish a causal link between settlers’ culture and FLFP in US counties, I must assume that the spatial distribution of the relative share of settlers from places with liberal gender attitudes was random. The process of selection and sorting settlers into newly created US counties based on specific local conditions and/or self-selection of settlers with particular characteristics, including gender-related values, poses challenges to identifying the causal effects of settlers’ culture.

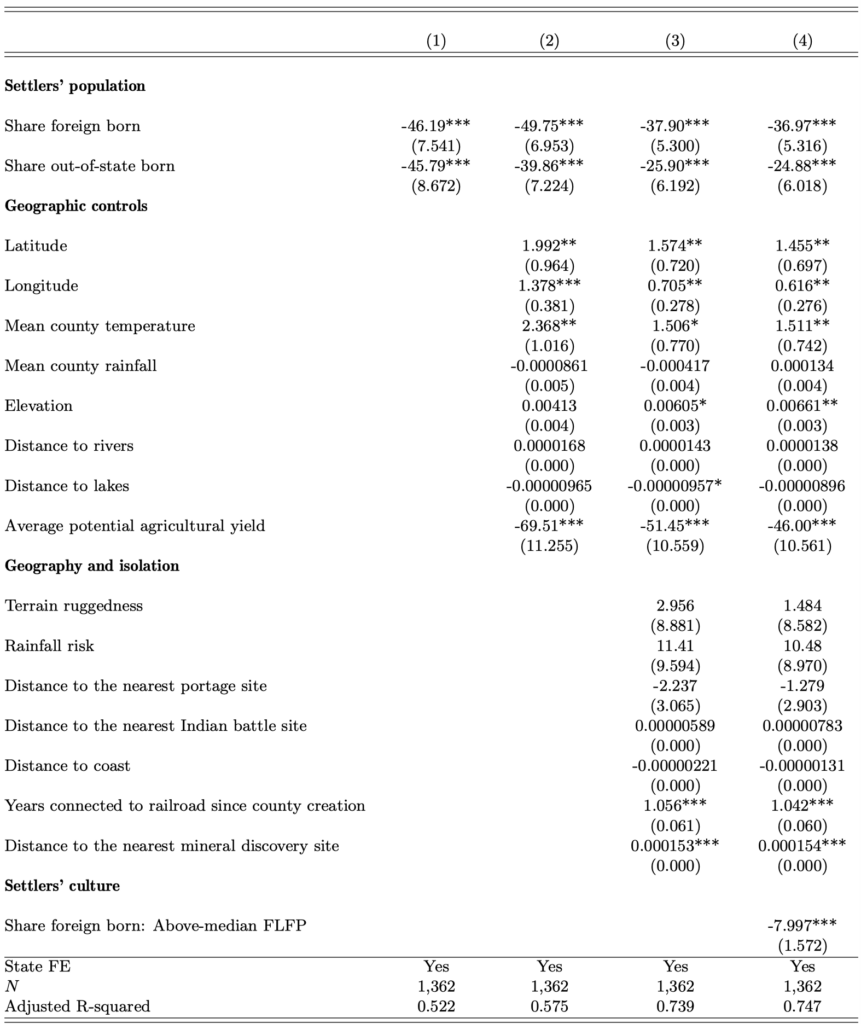

I address this potential endogeneity bias by incorporating a set of covariates that are likely to influence both the composition of settlers and gender norms in US counties. These covariates account for local conditions, including economic opportunities. In addition to county-level geographic characteristics, the covariates include terrain ruggedness, rainfall risk, distance to the nearest portage site, distance to the nearest Indian battle site, distance to the coast, number of years the county has been intersected by railroads since its creation date, and distance to the nearest mineral discovery site. Furthermore, to consider employment opportunities, I include controls for contemporaneous male labor force participation (MLFP) in US counties.

Of course, it is impossible to control for all plausible factors that may correlate with culture and also influence the spatial distribution of settlers from places with liberal gender attitudes. Therefore, I employ an IV strategy that isolates potentially exogenous variations in settlers’ culture. In Section 5.5, I provide a detailed discussion of the strategy, which draws inspiration from the work of Sequeira et al. (2020) and Bazzi et al. (2020). This strategy aims to isolate push factors by predicting migrant outflows from Europe based on climate shocks.

There are, however, other potential threats to my identification, in addition to location-specific confounders and, consequently, issues related to settlers’ selection and sorting. First, one might argue that the timing of county creation could be influenced by the composition of settlers, where a more homogeneous population might expedite the county creation process. In other words, endogeneity in county formation could be a concern. Second, defining settlers as the first inhabitants of newly created counties using the first available census data might be problematic if people had been residing in these counties long before their creation and, consequently, long before the first US Census was conducted. I address these concerns in Section 6.

Last, the correspondence assumption between settlers’ culture and the dominant culture in the sending country/state of settlers might not hold if settlers hold beliefs, preferences, and values that do not align with the norms of their country/state of birth. In other words, the cultural correspondence assumption might be challenged if there is a selective migration from their places of origin. While the IV approach mitigates this concern by isolating migration push factors based on climate shocks, I further investigate the validity of the cultural correspondence assumption in Section 6.

4.3 Model Specification

I now present the model specification used in this paper. I estimate the following specification using ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation:

(1)

where captures a given county

, created in a given state

, in a given decade

.

is the county-level FLFP. For the short-run (long-run) analysis, data on FLFP are extracted from the 1st (10th) full-count US Census available after county creation date.

is the distribution of foreign, out-of-state, and in-state born individuals out of the total population.19The shares of foreign, out-of-state, and in-state born individuals (omitted category) add up to the entire population in a given US county. The estimated coefficients on the share of foreign and out-of-state born individuals are thus relative to the share of in-state born individuals.

is the independent variable of interest proxied with values and beliefs from settlers’ country/state of birth using two different measures.20While, conceptually, examining the effects of hosting more out-of-state and more foreign-born settlers from gender-liberal places should not differ, studying the effects separately allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the overall effects of the characteristics of these two groups of early settlers and enables a comparison of their relative effects. The first measure encompasses FLFP in sending countries, quantified using a range of metrics. The second measure explores the chronological implementation and passage of women’s financial rights across US sending states.

includes a list of covariates susceptible to affect both the composition of settlers and gender norms in US counties, directly and indirectly, through economic development and other channels. The list incorporates baseline county-level geoclimatic controls such as latitude, longitude, mean county temperature and rainfall, elevation, distance to lakes and rivers from the county centroid, and average potential agricultural yield.21This latter measure of agricultural suitability, as provided by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, serves as a suitable proxy, for instance, for local economic development and the demand for female workers in agriculture. To these, I add a set of demographic controls characterizing settlers’ population, including the share of prime-age population (Bazzi et al. 2020), the share of literate population (Bazzi et al. 2020), the sex ratio computed as the ratio of the male over the female population (Baranov et al. 2023; Grosjean and Khattar 2019), the share of the single population (Bazzi et al. 2020), and the children-to-women ratio computed as the ratio of the number of children under 5 years of age over the number of women in their childbearing age times 1,000.

Finally, I also include additional controls that capture counties’ geography, isolation, conflict with Native Americans, and other factors that may be correlated with settlers’ location, culture, and gender norms in US counties. Specifically, I control for terrain ruggedness (Nunn and Puga 2012), rainfall risk (Davis 2016), distance to the nearest portage site (Bleakley and Lin 2012), distance to the nearest Indian battle site, distance to the coast, number of years that the county has been intersected by railroads since its creation date, and distance to the nearest mineral discovery site (Couttenier et al. 2017). $ and

are state and decade of county creation fixed effects, respectively, to account for time-invariant differences across states and common decade-specific shocks.

is the error term. My standard errors are clustered on 60-square-mile grid cells (Bester et al. 2011).

5 Main Results

In this section, I explore systematic evidence regarding the short-term historical relationship between settlers’ culture and FLFP at the county level. Subsequently, I replicate this analysis in the long run to investigate the enduring connection between settlers’ culture and FLFP as well as gender attitudes today. I also examine the correlation between the culture of later settlers and FLFP in US counties, both in the short and long term. This examination assists in discerning the cultural impacts of later settlement.

5.1 Settlers’ Culture: Short-Run Analysis

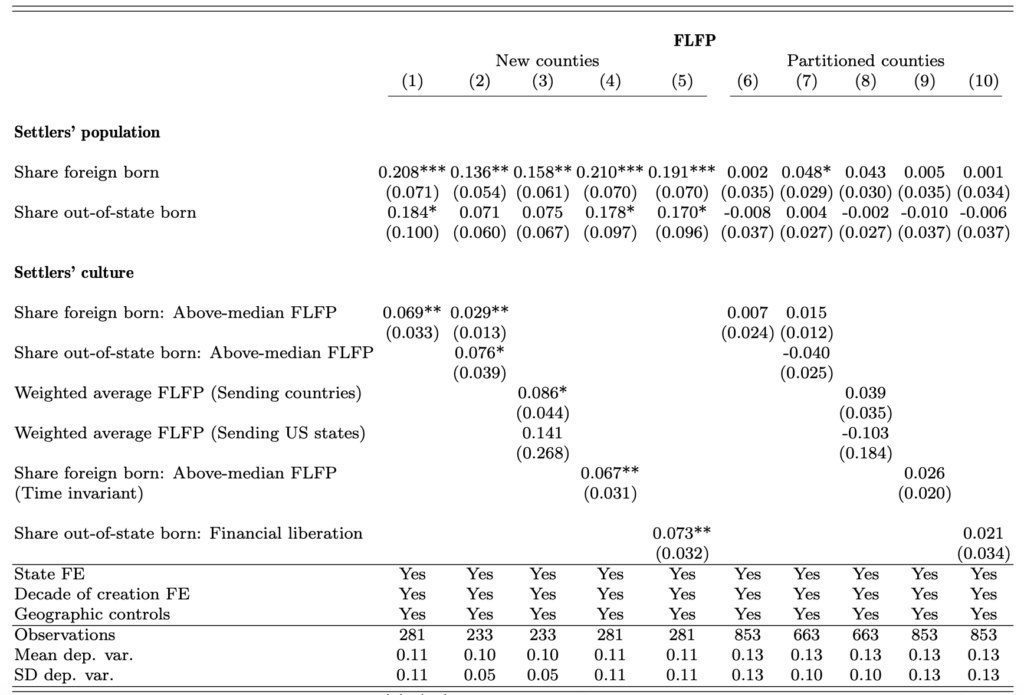

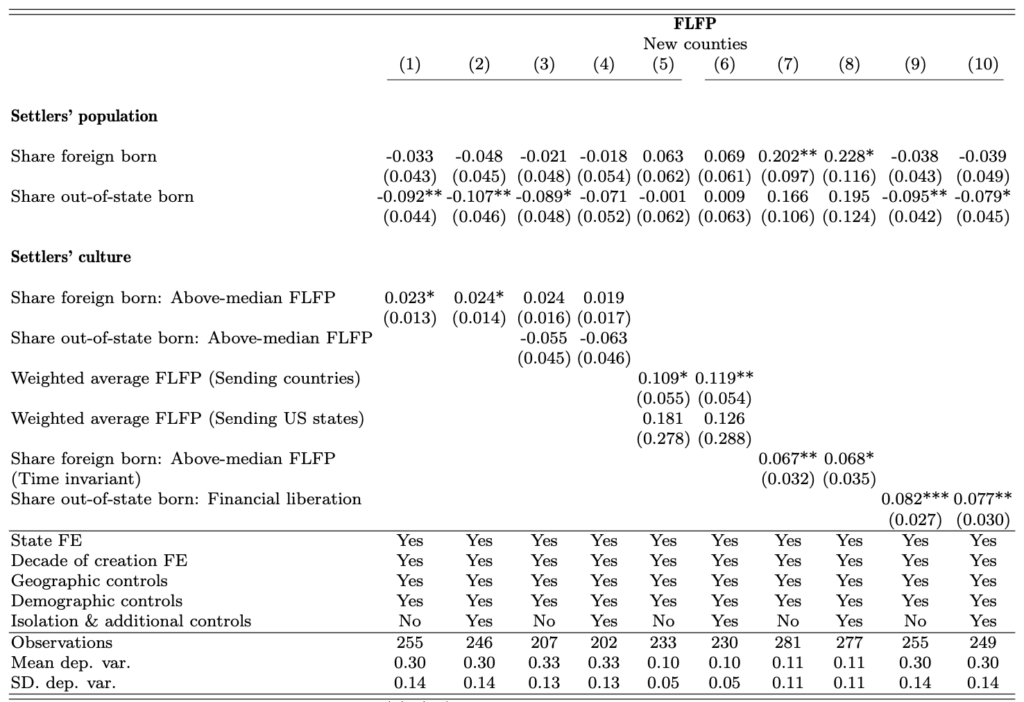

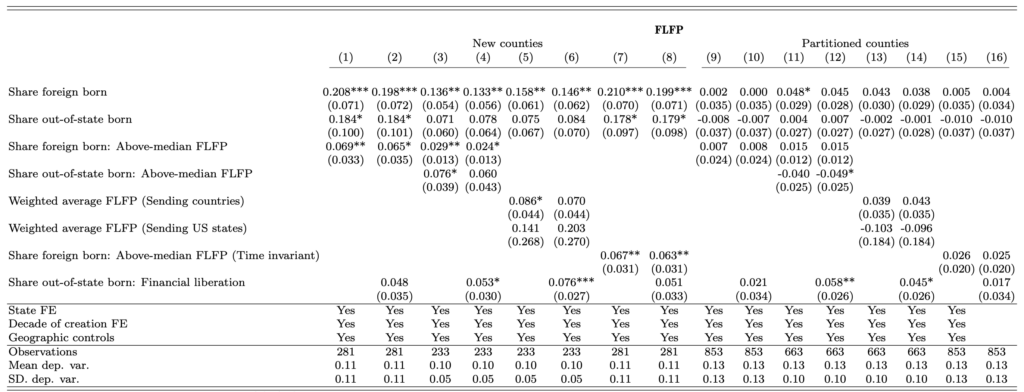

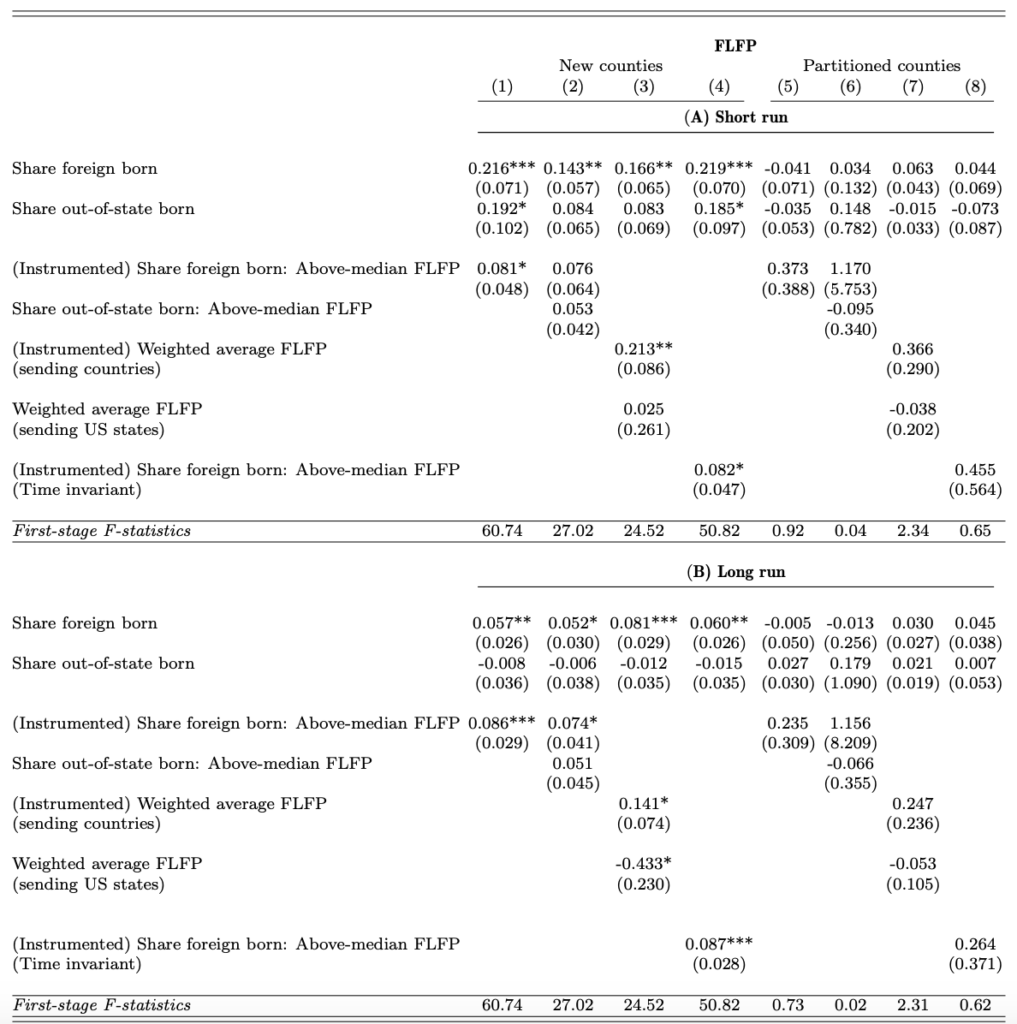

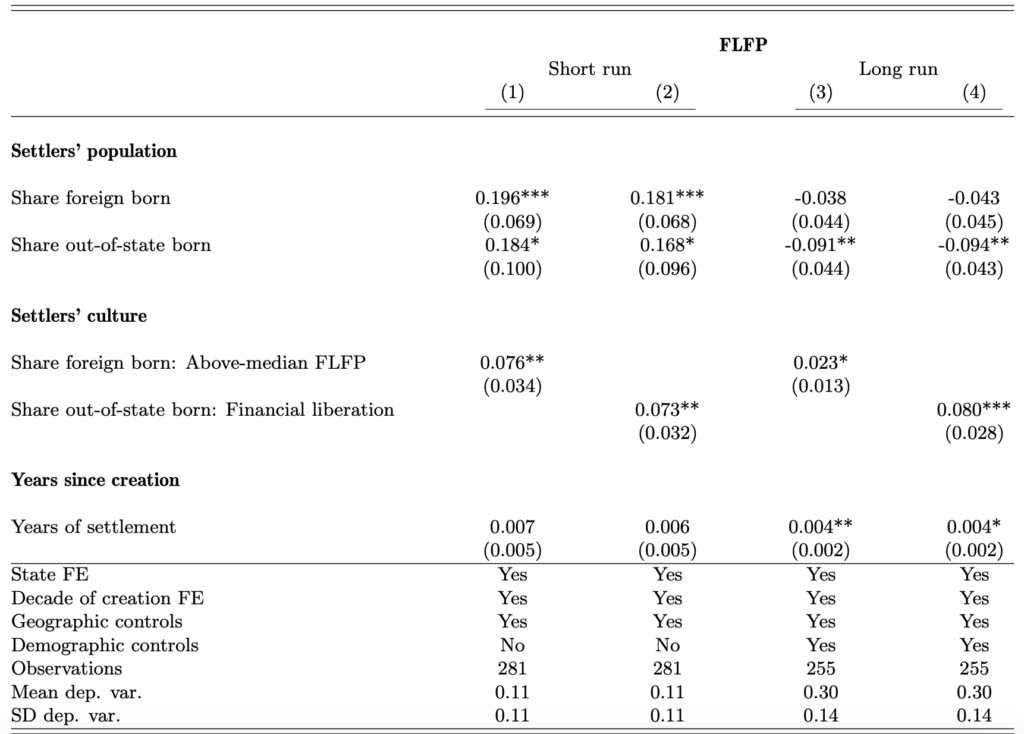

I begin by investigating the connection between settlers’ culture and gender norms in US counties at the time of their creation. Table II presents the results of estimating Equation (1), with the outcome variable of interest being FLFP in US counties in the short run. Data on labor force participation are extracted from the first US Census data available after the county’s creation. Throughout the analysis, I control for state and decade of county creation fixed effects as well as geographic countylevel variables. In columns (1)–(5), my main sample comprises new counties that were exclusively created between 1840 and 1940 from noncounty areas. In columns (6)–(10), I narrow down the sample to partitioned counties.

Contingent on the proportions of foreign-born, out-of-state born, and in-state born settlers within the total county-level population, I investigate whether a higher proportion of early settlers from places with liberal gender attitudes is correlated with FLFP in US counties in the short run. In columns (1)–(4) and (6)–(9), I assess settlers’ culture by using FLFP levels in sending countries to capture the values and beliefs of foreign-born settlers, employing various metrics. In columns (5) and (10), I use the variations in the timeline of the enactment of women’s financial liberation to calculate the proportion of out-of-state-born settlers originating from states where women had property and earning rights.

The results from my main sample analysis, presented in column (1) and limited to new counties created from noncounty areas between 1840 and 1940, show a positive and statistically significant correlation between the proportion of foreign-born settlers from countries with above-median FLFP and FLFP in US counties. The estimate in column (1) indicates that a 1 percentage point increase in the share of foreign-born settlers from countries with above-median FLFP is associated with approximately a 0.07 percentage point increase in FLFP in US counties.22The mean of the dependent variable, FLFP, in my primary sample of new counties is 0.11, with a standard deviation of 0.11. In my alternative sample of partitioned counties, the mean is 0.13, with a standard deviation of 0.12.

In column (2), I assess the sensitivity of the results to the definition of settlers’ culture, where I use FLFP data from their sending origins. Out-of-state born settlers constitute 64 percent of the early settler population, suggesting they may have a relatively more significant influence on local culture. Therefore, I examine the impact of the proportion of out-of-state born settlers from US states with above-median FLFP.

However, it is important to note that I aim to gather data on FLFP from the same decade or a decade or two earlier compared to when I study the population of out-of-state born settlers. These data may not be available for counties that were not yet created or were recently established, meaning it is not always possible to use FLFP from sending states to capture the cultural beliefs of out-of-state born settlers. Additionally, the data required to construct this measure are also used to create the main dependent variable of interest. As a result, I refrain from including the share of out-of-state born settlers from above-median FLFP states in the main specification for the rest of the paper and limit the analysis to a sensitivity check. The reduced sample size is due to missing data on FLFP in 1850 from the US Census, which is necessary to calculate the proportion of out-of-state born settlers from high-FLFP states.

The results presented in column (2) indicate that having a higher proportion of settlers from countries and states with high-FLFP is positively associated with a greater level of FLFP in the hosting counties. Compared to column (1), the effect for the share of foreign-born settlers from countries decreases in magnitude, yet the point estimate remains statistically significantly robust.23The fact that the coefficient linked to the culture of foreign-born settlers decreases when the culture of out-of-state settlers accounted for suggests a positive correlation between these variables. The relatively low, yet positive, correlation between these two variables supports the hypothesis that migration flows from various locations are randomly distributed across US counties, considering the correlation in the average characteristics of two different types of migrants. The estimates in column (2) reveal that a 1 percentage point increase in the proportion of settlers from countries and states with above-median FLFP is associated with roughly a 0.03 and 0.08 percentage point increase in FLFP in US counties, respectively.

I then explore alternative measures of FLFP from sending countries. The results could be highly sensitive to the definitions of high-FLFP from sending countries as above median or mean. To address this concern, I use a weighted average of FLFP from sending countries, with weights based on the share of foreign-born settlers originating from a given country and residing in a specific US county. In addition, since the gender norms of source countries are measured in the same or preceding two decades, the key variable of interest could be influenced by the backward propagation of cultural norms by contemporaneous migrants or migrants in earlier waves in similar regions. To mitigate this potential issue, I employ a time-invariant measure of origin-country gender norms, which is defined using the earliest (known) FLFP data available for each country as of 1840.

The results presented in columns (3) and (4) of Table II corroborate the findings outlined in the primary specification (column (1)). Settlers’ culture, as proxied by alternative variations of FLFP from sending countries, remains positively and statistically significant, with a magnitude ranging from 0.07 to 0.09 percentage points. In column (5), the positive and statistically significant estimate for the proportion of out-of-state born settlers originating from US states where women had property and earning rights confirms a positive association with FLFP in the short run for my primary sample of new counties, with a magnitude of 0.073 percentage points.

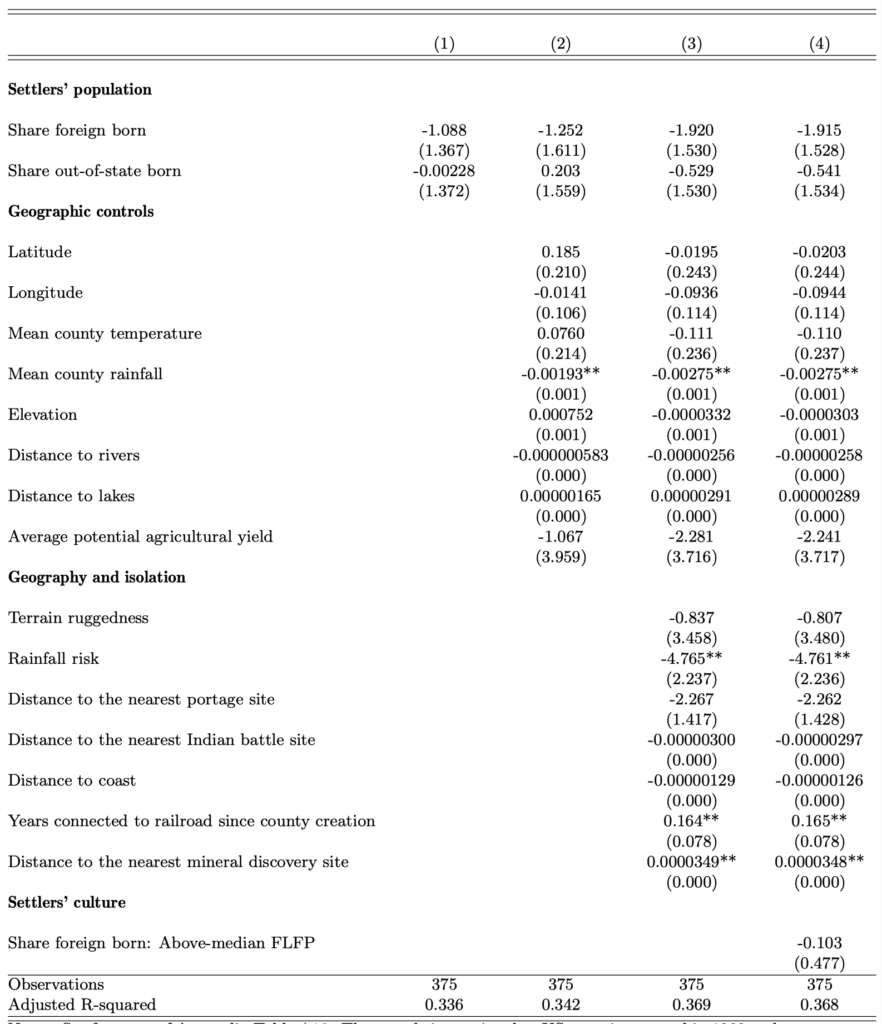

In columns (6)–(10), I replicate the same analysis for the sample of US counties that have been partitioned or subdivided from previously settled areas. I find evidence indicating the absence of a short-term historical relationship between settlers’ culture and FLFP in US hosting counties, which applies to measures of settlers’ culture.

5.1.1 Sensitivity Analysis

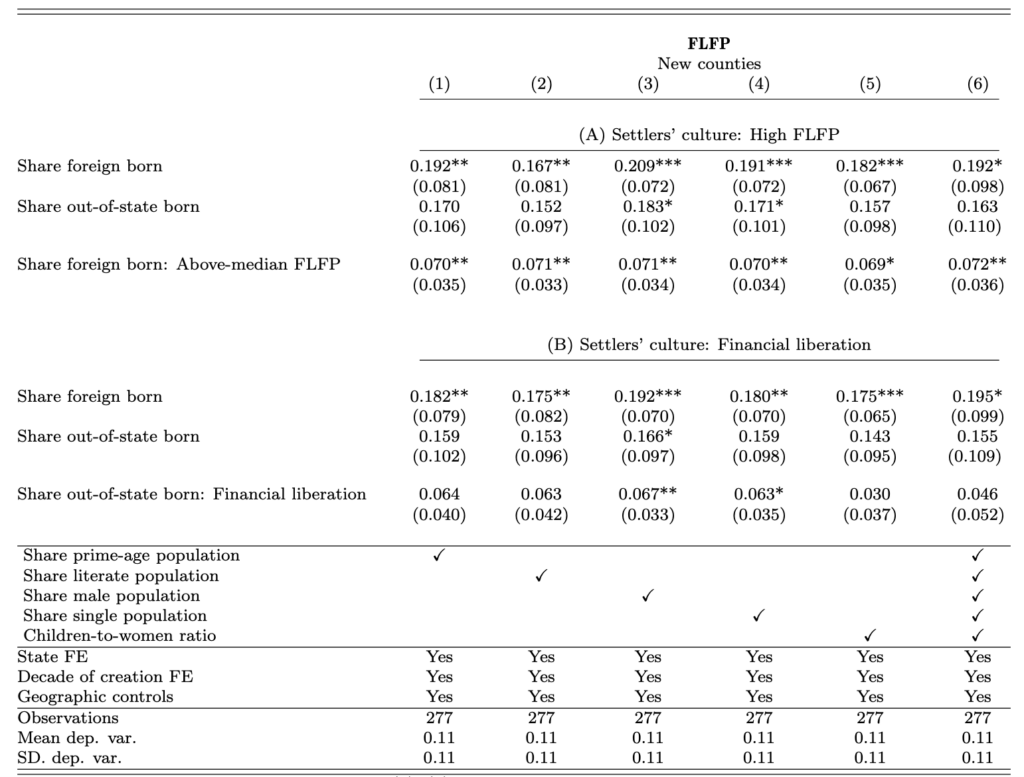

In Table III, I examine the robustness of the main results from column (1) of Table II by including a set of demographic controls. These controls encompass the share of prime-age population, the share of literate population, the sex ratio calculated as the ratio of the male to the female population, the share of the single population, and the children-to-women ratio computed as the ratio of the number of children under 5 years of age to the number of women in their childbearing age, multiplied by 1,000. The dependent variable in columns (1)–(6) is FLFP in US counties in the short run for the sample of new counties.

In Panel (A), settlers’ culture is proxied for using FLFP from sending countries. In Panel (B), settlers’ culture is proxied by women’s financial rights. Columns (1)–(5) in Panels (A) and (B) present the results of introducing each of these controls individually, and then all of them are introduced simultaneously in column (6). I find that having more settlers from high-FLFP countries remains strongly positively correlated with FLFP in US counties in the short run. The magnitudes of the point estimates document about a 0.07 percentage point increase in FLFP.24The results from Panel (B) reveal a high sensitivity to including these demographic controls. A plausible explanation is that the latter might directly be related to the treatment. An extreme example is that across sending populations, the FLFP rate is perfectly correlated with the literacy rate.

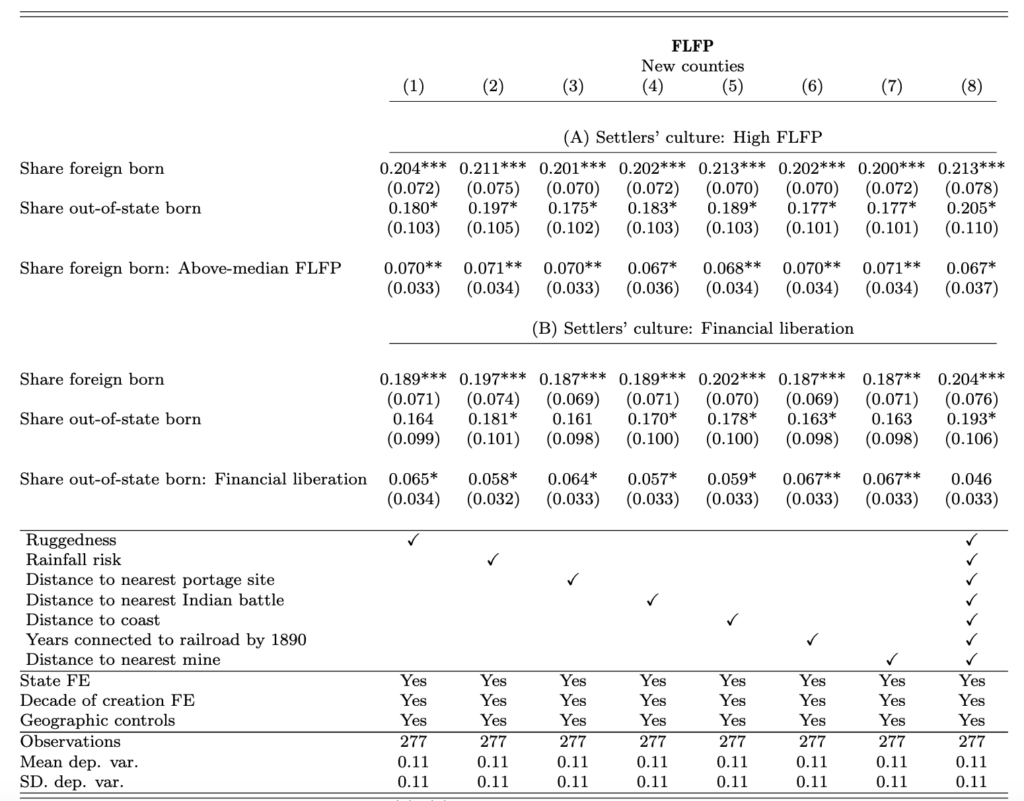

Next, I introduce additional controls that capture counties’ geography, isolation, and development levels that may be correlated with settlers’ location, culture, and gender norms in US counties. The structure of Table IV is similar to the one in Table III. I control for terrain ruggedness, rainfall risk, distance to the nearest portage site, distance to the nearest Indian battle site, distance to the coast, number of years that the county has been intersected by railroads since its creation date, and distance to the nearest mineral discovery site separately in columns (1)–(7) and simultaneously in column (8). I document that my main results remain robust to including these plausible confounding factors.

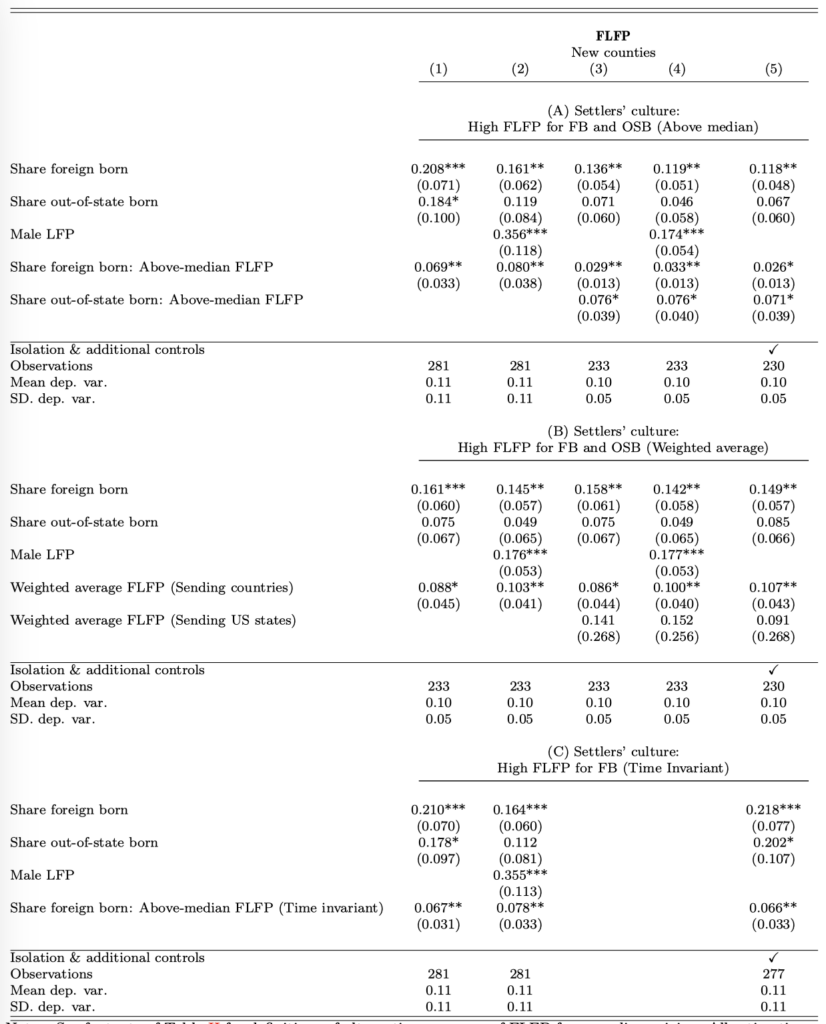

While I have assessed the sensitivity of the results to the definition of settlers’ culture using FLFP from sending origins in columns (2)–(4) of Table II, and have examined the robustness of the main results (column (1)), I have not yet tested the robustness of these alternative definitions to including location-specific confounders that could influence both the culture and locational decisions of migrants (i.e., as conducted in Tables III and IV). I thus further probe the analysis in Table V. Panels (A), (B), and (C) display the results using various measures of settlers’ culture: the share of foreign and out-of-state born settlers from countries/US states with above-median FLFP; a weighted average of FLFP from sending countries/US states, weighted by the share of foreign-born (out-ofstate) settlers residing in a given US county and originating from a given country (US state); a time-invariant measure of origin country gender norms, defined using the earliest (known) FLFP data available for each country as of 1840, respectively.

Column (1) of Panel (A) repeats the main results reported in column (1) of Table II. Column (1) of Panel (B) shows the results from using the share of foreign-born settlers from high-FLFP countries, using a weighted average of FLFP. Column (1) of Panel (C) repeats the results obtained in column (4) of Table II. In the goal of further accounting for county-level local economic conditions, I control for contemporaneous MLFP in US counties in column (2) of Table V. My findings remain robust to including this variable.

The results reported in column (3) of Panels (A) and (B) repeat my findings from Table II, particularly columns (2) and (3). In column (4) of Panels (A) and (B), I account for MLFP, and in column (5) of Panels (A), (B), and (C), I account for county-level additional controls that capture counties’ geography, isolation, and development levels. Overall, I document that alternative definitions for FLFP from sending origins remain robust to including local economic and geographic conditions.

Last, I examine the impact of settlers’ culture on FLFP in the short run using variables that capture values and beliefs from their places of origin in one regression. The results are reported in Appendix Table A3. The sample of US counties is restricted to new counties in columns (1)–(8) and partitioned counties in columns (9)–(16). The dependent variable in columns (1)–(16) is FLFP in US counties in the short run. State fixed effects, decade of county creation fixed effects, and county-level geographic controls are included throughout.

Columns (1), (3), (5), and (7) replicate columns (1)–(4) of Table II. Columns (2), (4), (6), and (8) are amended to additionally account for the share of out-of-state born settlers from states where women were granted financial rights. The results in Appendix Table A3 indicate that settlers’ culture, as proxied by the share of foreign-born settlers coming from high-FLFP countries (measured through various metrics), remains robust even when the other measure of culture (financial liberation of women) is included. The estimates continue to be positive and statistically significant throughout. Columns (9)–(16) repeat this analysis for partitioned counties. Once again, the findings suggest the absence of a short-term relationship between settlers’ culture and FLFP.

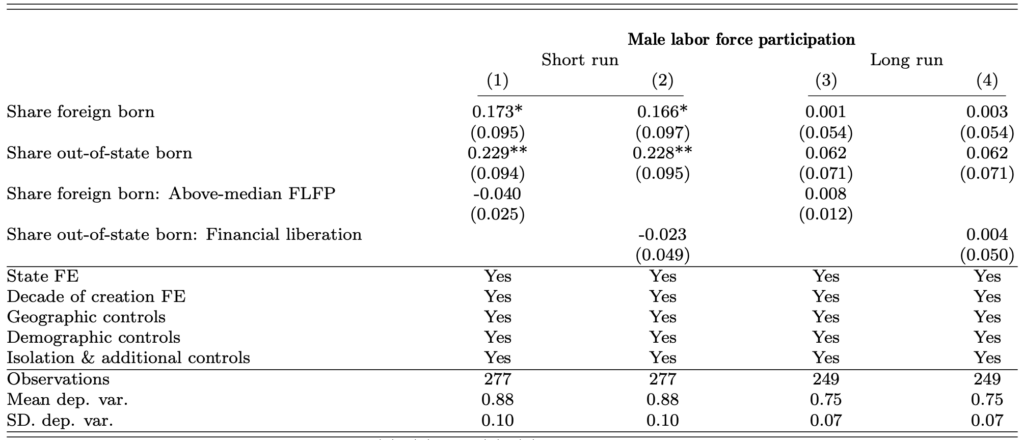

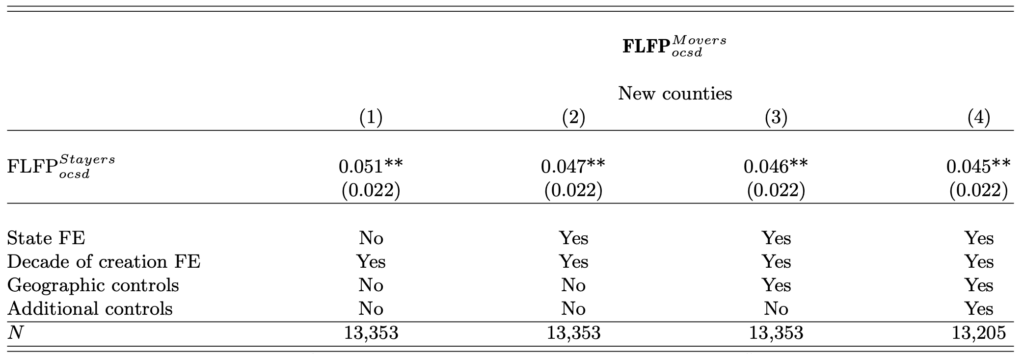

5.2 Later Settlers’ Culture: Short-Run Analysis

In this subsection, I directly test Zelinsky’s predictions by examining whether the culture of later settlers matters for cultural formation in hosting areas. In other terms, the purpose of this analysis is to investigate the cultural impacts of later settlement. If early settlers have a unique and dominant effect on the local culture, then later settlers’ culture should not determine gender norms differences across US counties.

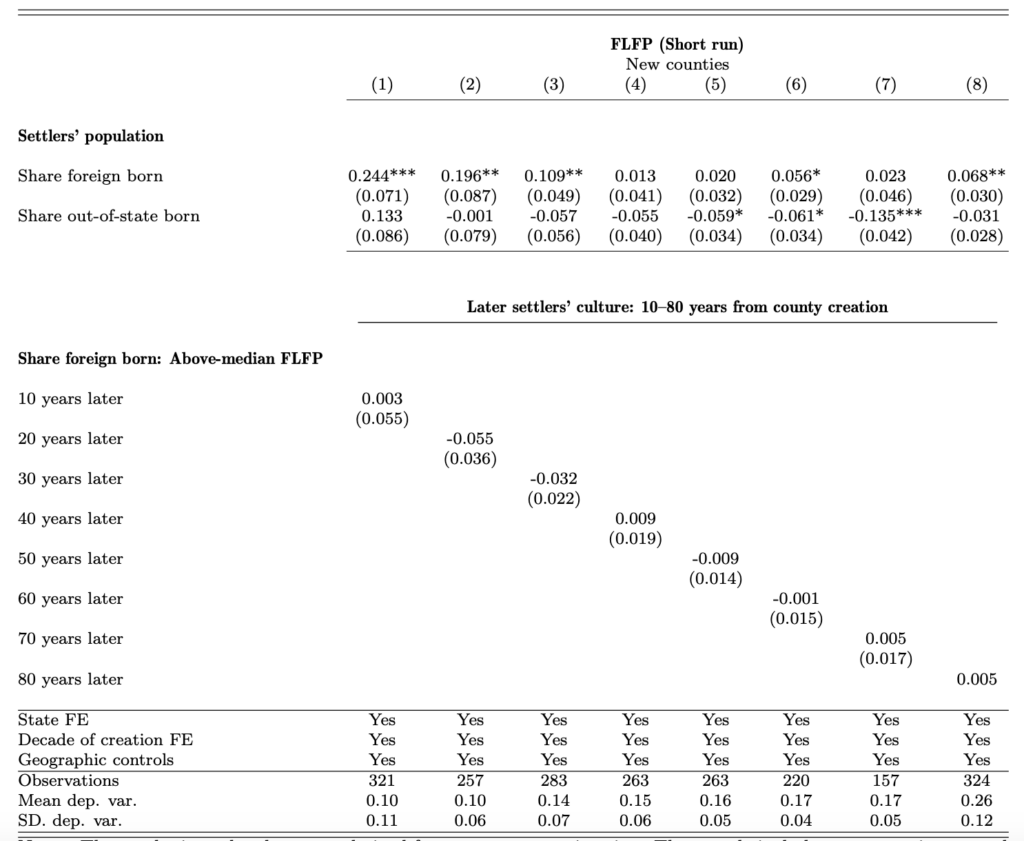

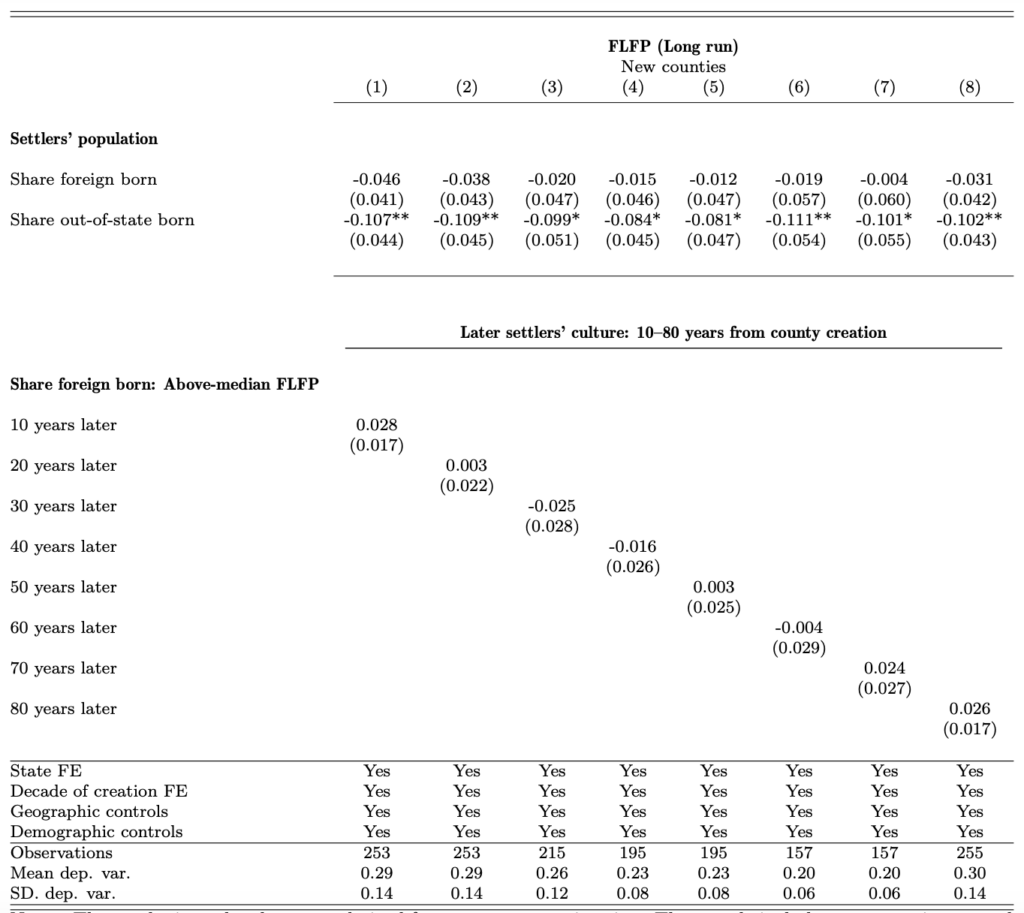

In Table VI, I probe the relationship between later settlers’ culture as measured by the share of foreign-born settlers from high-FLFP countries and FLFP in US counties in the short run. The result in each column are derived from a separate estimation and are based on a slightly altered version of Equation (1), where settlers’ population and culture capture later rather than early settlement.

I compute later settlers’ population using data from the 2nd, 3rd, … 8th census available after the county creation date. The dependent variable in columns (1)–(8) of Table VI is FLFP in US counties in the short run using from the 2nd, 3rd, … 8th census available after the county creation date (i.e., 10, 20, … 80 years later), respectively. Stated differently, columns (1)–(8) repeat the main analysis and specification 10, 20, … up to 80 years post-initial settlement and check whether the culture of people who inhabit newly created counties 10, 20, … 80 years after its creation determine its FLFP levels.

In column (1), later settlers’ culture for each US county is measured using the share of foreign-born individuals who reside in that county 10 years after its creation and who originate from sending countries. Settlers’ culture in columns (2)–(8) is measured using the share of foreign-born individuals who reside in that county 20–80 years after its creation and originate from high-FLFP sending countries.

The findings across columns (1)–(8) reported in Table VI reveal that later settlers’ culture does not determine FLFP in the short run.25The analysis is in the short run given that settlers’ culture and FLFP in US counties is measured at the same time (i.e., 10, 20, … 80 years postcounty creation date). I then repeat this analysis, focusing on the long-term FLFP in US counties as the dependent variable, based on the 10th census available after the county creation date. Settlers’ culture is measured using the share of foreign-born individuals who reside in that county 20-–80 years after its creation and originate from high-FLFP-sending countries. It remains crucial to mention that the results from this analysis do not allow me to simply reject the importance of later settlers’ culture, particularly for persistence. Later settlers matter as a result of the first settlement through following migrants’ clustering (see Section 5.9 for more details).

The findings from this analysis provide evidence in support of Zelinsky (1973)’s doctrine that the first group of people matter much more for cultural formation than the contribution of new immigrants a few generations later.

5.3 Long-Run Analysis

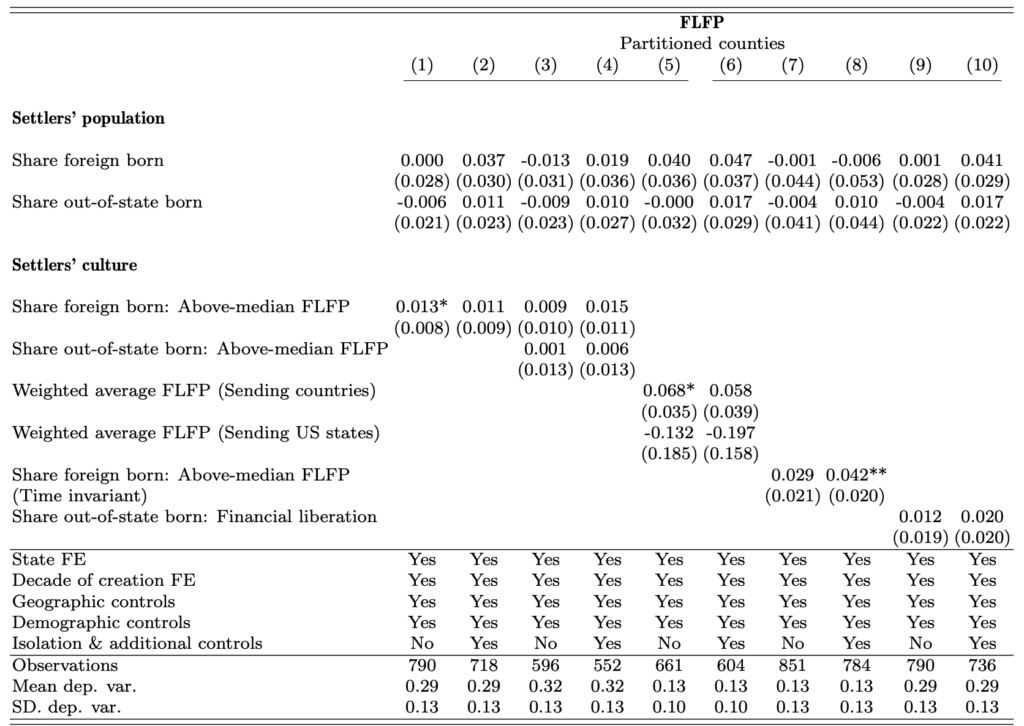

I now turn to the long-run relationship between the culture and gender norms of early settlers in the United States and their impact. This analysis examines the influence of foreign and out-of-state born settlers from places with liberal gender attitudes on gender norms in US counties, specifically during their early stages of cultural and institutional development, and the long-run effects of this influence. I begin by estimating Equation (1) in the long run. The dependent variable in columns (1)–(10) of Table VII is FLFP in US counties, using data on labor force participation from the 10th US Census available 100 years after each county’s creation. The analysis is limited to new counties throughout.

Exploiting settlers’ culture, I document an increase in FLFP 100 years later, with a higher share of foreign-born settlers from countries with above-median FLFP. The estimate presented in column (1) of Table VII suggests that a 1 percentage point increase in this share is associated with an approximately 0.02 percentage point increase in FLFP for the primary sample of new US counties in the long run. This result remains consistent even after accounting for counties’ demographic, geographic, isolation, and development characteristics. It also holds when considering alternative measures of settlers’ culture using FLFP from their respective origins. These long-term findings align with the results of FLFP a few years after county creation (short-run results reported in Table II), providing evidence for the enduring impact of settlers’ culture. In columns (9) and (10) of Table VII, I find that this relationship persists when using women’s financial liberation as a proxy for settlers’ culture.26I conduct a similar analysis for counties categorized as partitioned, as shown in Appendix Table A4. These results confirm there is no long-term relationship between the culture of initial settlers and the FLFP in US hosting counties.