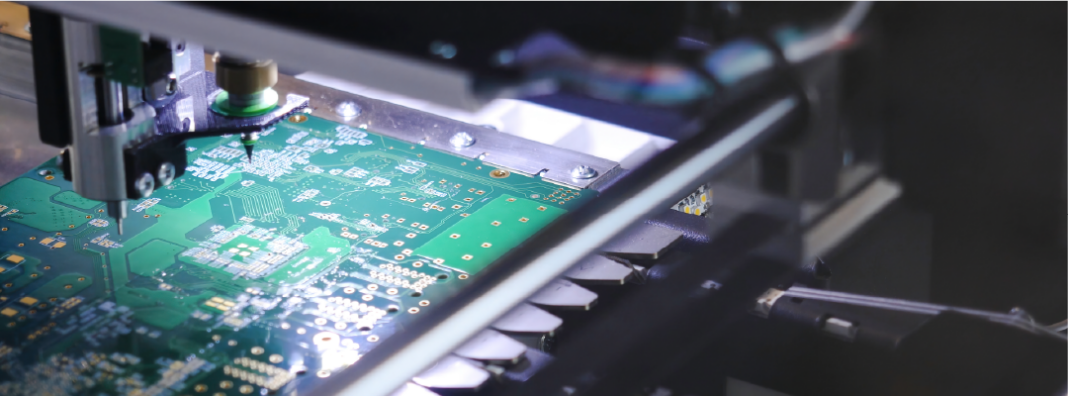

In December, Samsung delayed a Texas-based chip manufacturing facility’s start date. In January, the Taiwanese chip manufacturing company TSMC pushed back one of its planned Arizona plants. The reason? Workforce shortages. Two years after the U.S. passed legislation providing $280 billion over the next decade to spur the development of its semiconductors industry, such delays represent significant hiccups in America’s plan to boost our ability to build advanced computer chips.

The U.S. has provided significant investments and support for chip manufacturers in financial terms. However, you need more than financing to run a business. An often-overlooked reform to boost manufacturing in the high-tech sector is expanding skilled immigration. Our new research on the largest skilled immigration program in the U.S., the H-1B visa, suggests it is one of the missing pieces in successfully bringing more high-tech manufacturing within our borders.

It’s no surprise that there’s a need for additional workers who understand chip manufacturing. Consultants have projected hundreds of thousands of missing workers. This number grows to 1.4 million by 2030.

In the case of TSMC, this workforce shortage has been well-reported as a concern for more than two years ago. Lacking workers with the right training was reemphasized in their January announcement of the delay.

The same factor is at play in the case of Samsung’s plant delays. Samsung joined with the University of Texas in 2023 to create a “talent pipeline” for the state’s semiconductor industry.

These kinds of investments in domestic talent will certainly be one part of the solution to the skilled workforce shortage. To this end, the CHIPS and Sciences Act provides hundreds of millions in support for workforce development. These are commonsense investments in the U.S.’s domestic workforce.

However, training takes time. The U.S. needs to bring in workers ready to work today if it is serious about jumpstarting chip manufacturing.

Measuring the effect of H1-B visa holders on U.S. tech

This is where our new study comes into play. We are the first to examine the impact of skilled immigration policy reforms on young firms in the high-tech sector. Using data for which firms received an H-1B visa in fiscal years 2014 and 2015, we can see the effects that skilled immigration has on high-tech firms and their success.

For example, we find that firms that secured all of the foreign workers that they requested in a given year are more likely to survive in the next 5 years. On average, they have a 2.6 percentage point higher chance of survival compared to firms that received none of their requested H-1B visas. We see a stronger effect for younger firms, where chances of survival are higher by 3.5 percentage points.

This may seem like a small difference, but it has important consequences. It keeps the entire tech sector lean and fit. Our quantitative results predict that the increased business dynamism that follows the removal of current major H-1B policy-induced frictions would increase aggregate high-tech output by 26% and average firm productivity by 0.4%.

By promoting the success of young firms, immigration refreshes tech companies’ competitiveness and dynamism. Our model’s mechanisms suggest that higher young firm survival caused by lowering H-1B hiring frictions constrains the survival of less productive and older firms.

Furthermore, our results indicate that mitigating current frictions in skilled immigration policies has significant implications for increasing output and average firm productivity in the high-tech sector. That is, if we make it easier for U.S. companies to hire skilled talent no matter where they are from, we will make the U.S. economy stronger.

Based on our model mechanisms, measures that streamline the process for young firms can benefit the economy. At the simplest level, policymakers can capitalize on our research findings by streamlining access to skilled workers through the H-1B program by increasing the number of visas available, simplifying application procedures, reducing application fees, and/or making the transition for international students to work easier.

Our research is new, but we are not the first to point out that the U.S. needs to think of immigration as a tool for supporting homegrown innovation. Just a few months ago, Adam Ozimek and Connor O’Brien of the Economic Innovation Group proposed a “chipmakers visa” to support chipmaking in the U.S. More than a decade ago, a 2011 report from the Government Accountability Office pointed out that small firms often struggled when they did not receive the H-1B visas they requested and suggested that changes be made to improve the program.

The reality is that the H-1B program is the primary pathway for accessing foreign skilled labor in the U.S. today. Yet its stringent regulations frustrate companies, limiting their ability to grow and innovate in the country. The moves to train U.S. workers for these roles are vital–but the spark that will light the fire of success just might be a change to U.S. immigration policies.

Fortune Magazine

Fortune Magazine