The United States and the World’s Refugee Crisis

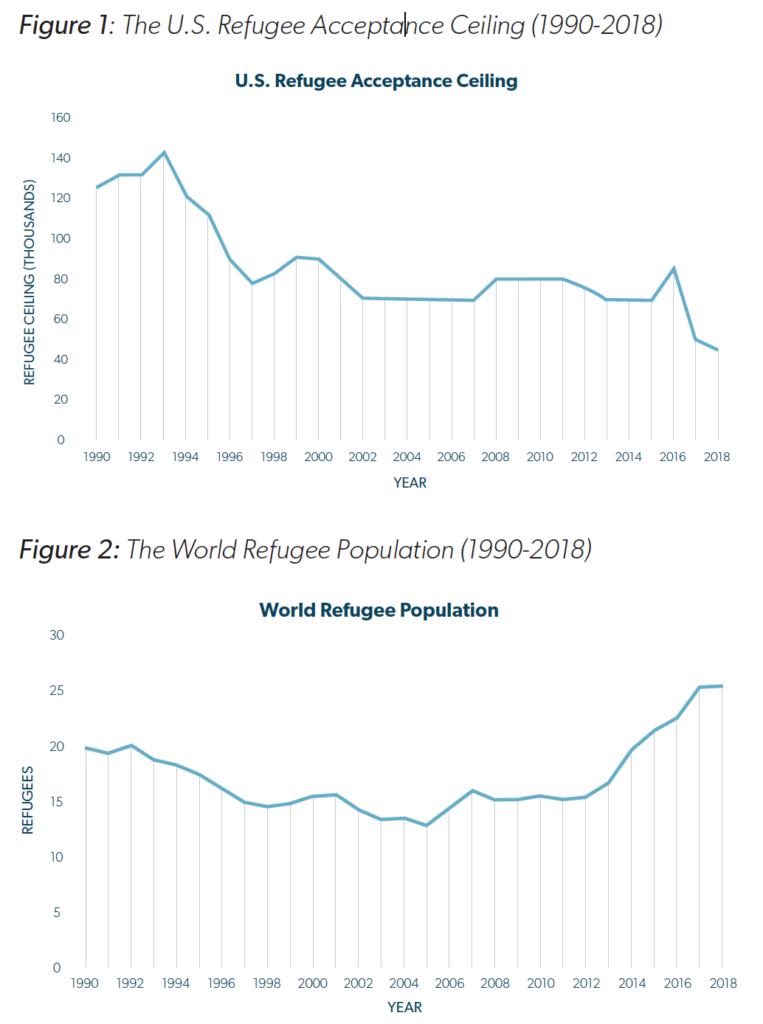

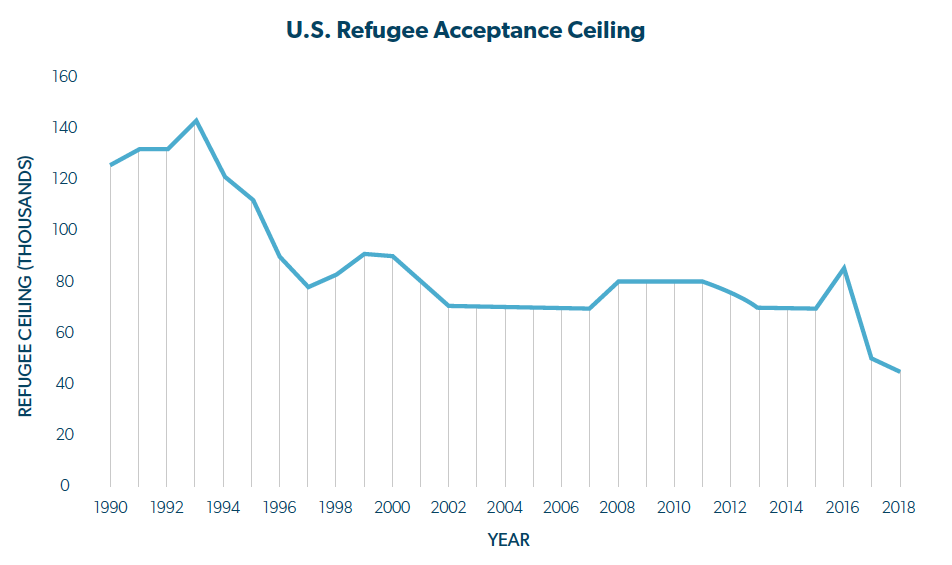

Current crises around the world, from Syria to Venezuela, have displaced an estimated 25.4 million refugees.1“Figures at a Glance,” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: USA, last modified June 19, 2018, http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html Historically, the United States has played a leading role in permanently resettling the world’s refugees, 2“Refugee population by country or territory of asylum,” The World Bank, accessed January 2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.REFG?end=2017&name_desc=false&start=1990&view=chart maintaining a refugee admission ceiling of 70,000 per fiscal year over the last two decades. 3“US Annual Refugee Resettlement Ceilings and Number of Refugees Admitted, 1980–Present,” Migration Policy Institute, accessed November 28, 2018, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/us-annual-refugee-resettlement-ceilings-and-number-refugees-admitted-united. As shown in figure 1, however, the current ceiling has been lowered to 45,000 for fiscal year 2018, which is the lowest level since 1980. 4Joel Rose, “Trump Administration to Drop Refugee Cap to 45,000, Lowest in Years,” NPR, last modified September 27, 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/09/27/554046980/trump-administration-to-drop-refugee-cap-to-45-000-lowest-in-years The global refugee population, by contrast, is growing.

Figure 1: The U.S. Refugee Acceptance Ceiling (1990-2018)

Figure 2: The World Refugee Population (1990-2018)

Sources: Data for refugee caps come from the Department of State Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, http://www.wrapsnet.org/admissions-and-arrivals/. Data for world refugee population come from “Refugee Population by Country or Territory of Asylum,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.REFG. Additional data points for years 2017–2018 were obtained from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Global Report 2017, http://reporting.unhcr.org/publications; “UNRWA in Figures 2017,” United Nations Relief and Works Agency, July 11, 2017, http://www.unrwa.org/resources/about-unrwa/unrwa-figures-2017; and “Figures at a Glance,” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: USA, last modified June 19, 2018, http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html.

At times, this reduction has been framed as a way to protect US workers from foreign competition. After all, the standard economic model of competitive labor markets predicts that an influx of foreign workers should depress wages for native workers if native workers are close substitutes to the incoming refugees— that is, if the refugees and natives have similar skill levels. 5 “4 Employment and Wage Impacts of Immigration: Theory.” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/23550. On the other hand, the same model predicts that additional refugees will boost the wages of native workers whose tasks are complementary. The crux of the debate over the optimal number of refugees largely comes down to determining the degree of substitutability between refugees and native workers.

Refugees in the United States typically work low-paying jobs, 6 William N. Evans and Daniel Fitzgerald, “The Economic and Social Outcomes of Refugees in the United States: Evidence from the ACS” (NBER Working Paper No. 23498, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, June 2017), https://doi.org/10.3386/w23498. which suggests that they are likely to compete with low-skilled workers and perform labor that complements the work of high-skilled individuals. Therefore, holding all else constant, an increase in the supply of labor from refugees should worsen labor market outcomes for low-skilled native workers while improving the circumstances of high-skilled native workers. The argument that accepting refugees may cause some US workers to lose jobs or face wage reductions has been the basis for many criticisms of refugee resettlement. The findings of empirical research, however, are not so cut and dry.

This paper summarizes the academic research on the impact of refugees on labor markets in the United States. In short, workers in US labor markets are dynamic and adapt in multiple ways to the entrance of refugees. Most estimates find no negative effects on native workers from influxes of refugees. The first section of the paper analyzes the localized effects of the influx of thousands of Cuban refugees to Miami in 1980. The next section takes a holistic perspective and examines the aggregate effects of refugees on the US labor market. The paper concludes with a discussion of the policy implications of existing research.

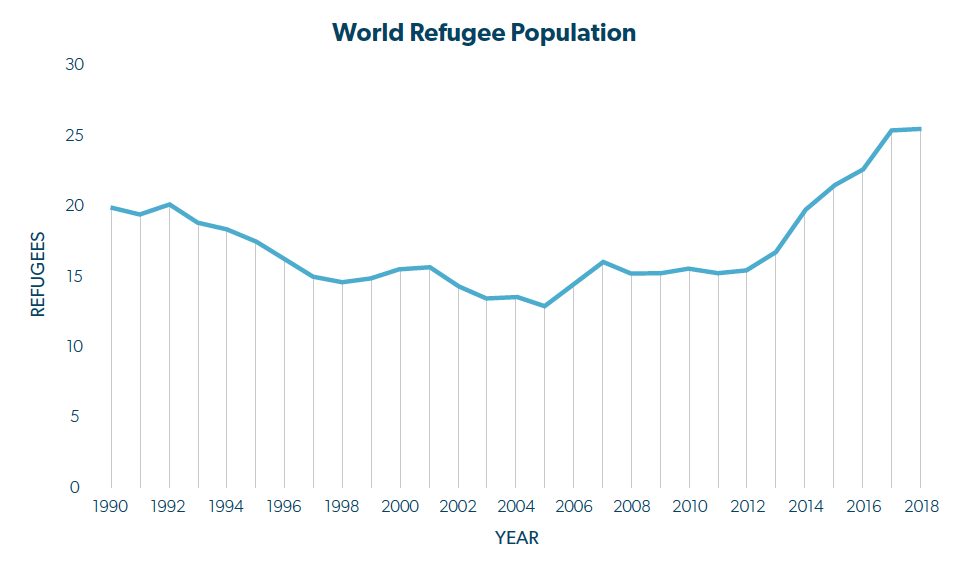

Table 1. Academic Findings on the Mariel Boatlift

Sources: a David Card, “The Impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami Labor Market,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 43, no. 4 (January 1990): 245–57.

b George J. Borjas, “The Wage Impact of the Marielitos: A Reappraisal,” ILR Review 70, no. 5 (October 2017): 1077–110.

c Giovanni Peri and Vasil Yasenov, “The Labor Market Effects of a Refugee Wave: Synthetic Control Meets the Mariel Boatlift,” Journal of Human Resources, January 30, 2018, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.2.0217.8561R1.

d George J. Borjas, “The Wage Impact of the Marielitos: Additional Evidence” (NBER Working Paper No. 21850, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, January 2016), https://doi.org/10.3386/w21850.

e George J. Borjas and Joan Monras, “The Labour Market Consequence of Refugee Supply Shocks,” Economic Policy 32, no. 91 (2017): 361–413.

f Michael A. Clemens and Jennifer Hunt, “The Labor Market Effects of Refugee Waves: Reconciling Conflicting Results” (NBER Working Paper No. 23433, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, May 2017, revised July 2017), https://doi.org/10.3386/w23433.

g George J. Borjas, “Still More on Mariel: The Role of Race” (NBER Working Paper No. 23504, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, June 2017), https://doi.org/10.3386/w23504.

Refugee Effects on a Local Labor Market: Insights from the Marielitos

Economists’ uncertainty regarding the labor market impact of refugees is highlighted by the many studies on the 1980 Mariel boatlift. That year, around 125,000 Cuban refugees, called the Marielitos, arrived in Miami, increasing the local labor supply by approximately 7 percent. 7David Card, “The Impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami Labor Market,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 43, no. 4 (January 1990): 245-257 A debate has recently been sparked between economists over whether or not the low-skilled Cuban refugees affected the wages and unemployment of low-skilled native Miami workers. Table 1 summarizes the major contributions to this debate, in chronological order.

The fourth column of table 1 shows the conflicting findings presented in the Mariel dispute and demonstrates the difficulty of identifying the labor market effects of the refugee influx given that it did not occur in a vacuum or as the result of a controlled experiment. Data quality issues and disagreements over methodology make identifying causality an ongoing challenge. Considering the continuing debate over the impact of this single, confined refugee influx, understanding the labor impacts of refugees on the entire country is far from a simple task.

Refugee Effects on the US Labor Market: A Holistic View

Looking beyond this particular episode, economists Anna Maria Mayda, Chris Parsons, Giovanni Peri, and Matthis Wagner have recently investigated the long-term effects of refugees on labor markets across the entire nation. Using the arrival and placement information of every refugee to enter the United States from 1980 through 2010, they analyzed the aggregate impact of refugees on the local labor markets to which they were resettled. They found no significant difference in wages or unemployment between native workers in labor markets where refugee arrivals represented 0.1 percent or more of the population and native workers in labor markets with a lower proportion of newly placed refugees. Individually examining the effect of refugees on the wages and employment of high- and low-skilled workers did not change the results. Refugees did not have an effect on either high skilled or low-skilled native workers. 8Anna Maria Mayda et al. 2017. “The Labor Market Impact of Refugees: Evidence from the US Resettlement Program,” US Department of State Office of the Chief Economist, 2017.

Other research offers some potential explanations for these zero effects of refugees on labor markets. For example, in a study using highly detailed labor force data on refugees being permanently resettled in Denmark and native workers there, economists Mette Foged and Giovanni Peri analyzed the effect of refugee inflows into Denmark from 1991 to 2008. They found that an increase of refugees had zero or slightly positive effects on the wages of low-skilled workers, a positive effect on the wage of high-skilled workers, and no effect on the unemployment of either group. They concluded that, owing primarily to differing language abilities, refugees are imperfect substitutes for lessskilled native workers. Thus, refugees push low-skilled workers to more-skilled, less manually intensive jobs and so have positive effects on natives workers’ wages, their employment, and their occupational mobility. 9Mette Foged and Giovanni Peri, “Immigrants’ Effect on Native Workers: New Analysis on Longitudinal Data,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 8, no.2 (April 2016): 1-34.

The findings from Denmark and the US suggest that there may be important factors researchers do not always fully consider when investigating the impact of refugees and immigrants on native US workers. One such factor is that native workers and refugees are inherently different, specifically regarding language ability, which may lessen the competition between the two groups for jobs requiring language aptitude. Another is that refugee placement programs in Denmark and the US provide job training and placement assistance, which may negate part of their impact on the labor market. As Mayda and her coauthors note, refugees may also spur occupational changes by native workers or lead them to pursue more education. Additionally, refugees do not solely increase the supply of labor — they also increase the demand for food, transportation, clothing, and other goods and services. In the same way, an influx of labor increases the incentive to invest in capital to pair with the greater labor supply. In the long run, additional investments in capital can bring incomes up as they make workers more productive. These factors likely mitigate any potential negative effects of refugees on wages and employment and provide a potential explanation for the studies finding zero effects in the United States.

Policy Implications: Depolarizing the Debate

The polarized public debate over the labor market impacts of refugees is made more challenging by the ongoing struggle of economists to arrive at a consensus because of imperfect data. Some find that refugees depress wages and increase unemployment among low-skilled US workers while increasing the wages of high-skilled workers. Many others conclude that refugees do not have any impact on the wages or unemployment of US workers. This ambiguity implies a need to recognize that refugees are not strictly beneficial or detrimental to the labor market. Openly acknowledging the lack of consensus in economic research and the possibility of zero effects would help to depolarize the current refugee debate and allow for more productive policy discussions.