An ancient Indian parable tells the story of a group of blind men who encounter an elephant for the first time. Each man explores a different section of the animal, one touching its ears, another its’ trunk, and so on with the side, legs, tail, and tusk. The man touching the tail believes an elephant is like a rope, while the one touching the tusk believes it is like a spear. Because of their limited reach, they gain only a partial idea of what an elephant is but none has the complete picture. Despite only having partial access, each man is still convinced that his section represents the whole.

A similar dilemma often plays out in national conservation policy. Our natural heritage is vast and made up of diverse but interconnected parts. People in one region may have knowledge of their own area’s resources and challenges but limited knowledge about other regions’ characteristics. Only by combining the knowledge of many can we gain an accurate picture of the national conservation landscape. The role of federal agencies like the Department of the Interior is to gather knowledge about the nation as a whole in order to make informed management decisions. Using input from the public, scientists, and federal employees’ own experience, policymakers aim to make informed decisions based on the best available scientific knowledge.

But much like the different parts of the elephant, different regions of the country provide unique insights about conservation. Crowdsourcing provides a way to combine these unique insights into a descriptive whole that can inform conservation policy. It provides another avenue through which conservation knowledge can find a pathway to the federal government’s decision-makers. Crowdsourcing is a tool that harnesses the enthusiasm of recreationists and volunteers to provide better conservation data at a lower cost.

An Old Idea with New Applications

Crowdsourced projects use modern technology to overcome the sometimes disjointed nature of conservation knowledge. The old adage that “two heads are better than one” reflects the fundamental insight of crowdsourcing — combining the knowledge of groups of people is a more efficient way to learn something than each person trying to learn it all on their own. Crowdsourcing is a very old idea that is finding new applications thanks to technological advances that make it easier for people to connect.

Modern crowdsourcing involves an open call for contributions from a large group of people, often non-expert volunteers. This open call allows many more people to contribute their knowledge than traditional projects that rely solely on researchers, scientists, and other professionals with expert knowledge. Technology like smartphones and the internet make it easier than ever to achieve that collaboration. The result is more data at a lower cost, and better data enables better decision making.

The eBird app is a crowdsourced project that allows volunteers to upload observations of bird species directly from their phone. Those observations are combined to create a worldwide database that shows the abundance and distribution of bird species. The app is very widely used, with over 500 million observations uploaded. Private groups, academic researchers, and the federal government have used the eBird database to make conservation decisions related to migratory patterns and species health.

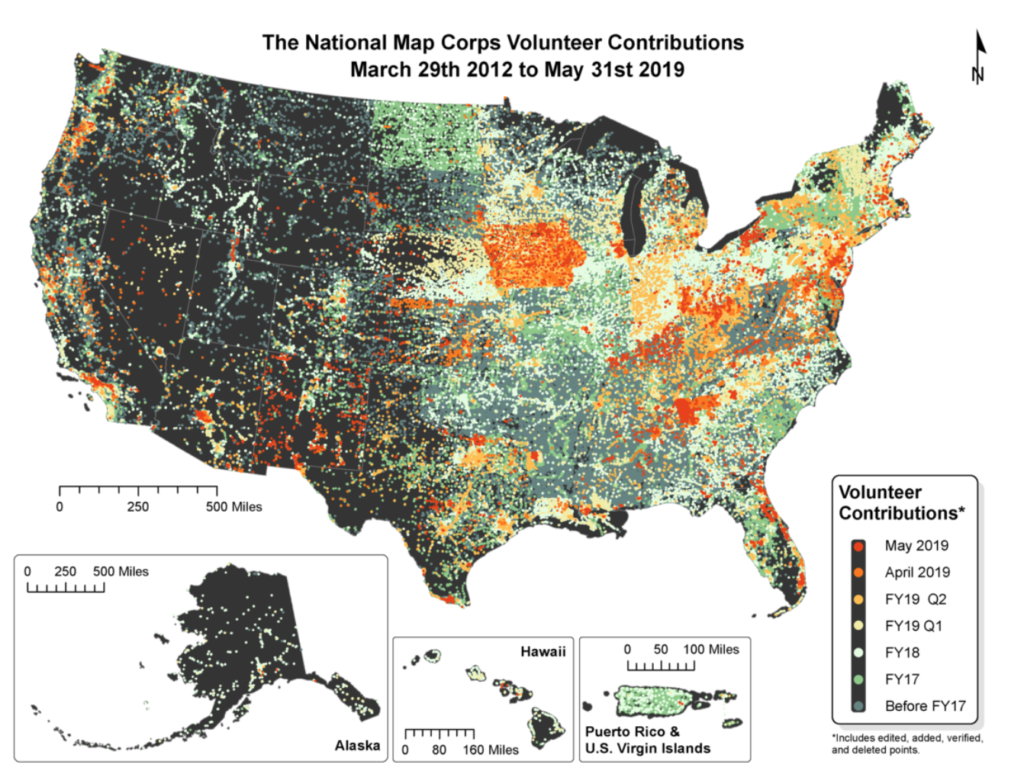

Crowdsourcing’s collaborative approach makes it an attractive tool for both federal and private conservation initiatives. One example of a collaborative project between volunteers and the federal government is the National Map — a collection of national, interactive maps created in part through crowdsourcing and organized by the US Geological Survey. The National Map Corps (TNMCorps) is a crowdsourced project that has produced a series of web-based products ranging from topographical maps to geospatial services. TNMCorps encourages citizen scientists to collect, edit, and verify data on man-made structures in order to fine-tune maps and information available to the public.

Thousands of people have contributed to this project so far, making over 150,000 submissions and edits. Data include information about boundaries, elevation, and geographic names. The National Map Project exemplifies a unique feature of federal crowdsourcing — the ability to gather data nationwide and use it for government-wide conservation goals. The maps enable better land management and policy decisions by providing updated information about building density in areas that endangered species rely on. This is of critical importance since habitat loss is a major threat to biodiversity. Crowdsourcing projects can also help federal agencies carry out their regulatory responsibilities related to conservation.

Source: US Geological Survey

Crowdsourcing Our Way to Better Policy Outcomes

Several federal agencies, including the US Forest Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and Fish and Wildlife Service, were created with a mandate to conserve land, water, and wildlife. The Endangered Species Act (among other legislation) requires these agencies to utilize the best available scientific knowledge when making decisions. The federal government has lots of mechanisms to gain knowledge about conservation targets — scientific research, public comment periods, and working partnerships with state and tribal governments. But these mechanisms are narrow, only allowing information to flow from the public to the government through specific avenues during designated time periods. The time and effort needed to learn how to navigate the bureaucratic process creates a barrier for many citizens hoping to be involved in conservation.

Crowdsourcing allows information to flow from the public to the federal government through much more open channels at a lower time and commitment cost from citizens. This lowers the cost of obtaining important conservation information while enabling the government to make conservation decisions based on the best available information. Conservation data is often sparse and difficult to obtain because of the large geographic range of plants and animals, their remoteness, and their movements. Without crowdsourcing, federal employees have to manually survey wildlife populations or monitor air and water quality. But through crowdsourced projects, volunteers can collect that information for them.

For example, the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) is a crowdsourcing project jointly managed by the US Geological Survey and the Canadian Wildlife Service. The project recruits volunteers to gather data on bird populations and migrations. The BBS database has been cited in peer-reviewed articles over 500 times. Federal agencies have also cited it in proposals to designate the Gunnison Sage-Grouse and Black-Backed Woodpecker as endangered species. Federal agencies have been clear that while the data is not flawless, it is essential to their decision-making process. For example, the US Fish and Wildlife Service said, “…the BBS is the only long-term trend information available for the mountain plover [and] an imprecise indicator. Even so, we acknowledge that this is the best available information on trends for this species.”

Making Federal Policy Work for Conservation

Crowdsourcing clearly has potential to add to the “best available scientific knowledge,” especially in a field where good data is scarce. Federal agencies have shown some willingness to use crowdsourcing to advance their conservation mandates but could do more to encourage its adoption. Lengthy and opaque regulatory processes to approve crowdsourcing projects may make federal agencies less inclined to use crowdsourcing. For example, the Paperwork Reduction Act (ironically) requires federal agencies to follow a time-consuming bureaucratic process to approve projects involving more than 10 people. Government paperwork requirements negate the advantages of crowdsourcing by reducing its efficiency and increasing its cost.

The value of modern crowdsourcing lies in its ability to connect large, diverse groups of volunteers using minimal infrastructure (often a simple app or website). This provides an opportunity to collect low-cost data essential to conservation issues, but bureaucratic rules designed in a past era make it difficult for federal employees to use crowdsourcing. A study from the Wilson Center found that federal employees who want to organize crowdsourced projects often feel unsure how to design projects in line with regulations.

Regulatory barriers to federal crowdsourcing projects make the federal government more reliant on the private sector and academic crowdsourcing projects. While private projects provide valuable information, they are not designed to fill gaps in federal agencies’ conservation knowledge, and any value-added is often coincidental, not by design. If the federal government wants to fully utilize crowdsourcing within its own processes, it will have to make its regulatory process more accommodating to gathering information from large groups of people.

Until that happens, partnerships between federal agencies and private groups can be a powerful tool for conservation, especially if they are designed with federal conservation goals in mind. Several examples already exist, harnessing the flexibility of the private actors with the goals of the federal government.

In one example, researchers at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park used geotagged public data from visitors to gain insight into resource strains stemming from visitor influxes. Park managers cited the dearth of visitor information in protected areas as “a main limitation in implementing proactive management strategies to minimize visitor impact on resources.” Through partnership with academic researchers, federal managers were able to gather valuable data that enabled them to make better land management decisions. The opportunities for similar public-private crowdsourcing collaborations are vast and easier to achieve than ever before thanks to modern technology.

America has a wealth of natural assets that deserve to be managed carefully using the best available data. In order for agencies to achieve that goal, they need to provide clearer guidance on what regulations apply to crowdsourced projects and embrace partnerships with private groups. There are many organizations across America that are working on conservation initiatives that can help the federal government conserve our land, water, and wildlife. Without accurate data from many sources, we are more likely to be like the blind men in the parable–convinced our narrow conception of a problem reflects the whole. Ensuring that the rules of government are aligned with the modern technology that enables crowdsourcing will allow us to understand the true state of our natural resources, so we can better protect them.