For many, being released from prison is anything but liberating. In fact, Gerald Alvarez “almost felt more secure” in the confines of prison. After serving two years of prison time, facing the outside world would be more than a culture shock—it posted vast unknowns, particularly about employment. As Alvarez hoped to put his past mistakes behind him, he had one major concern: that he wouldn’t be able to accomplish anything with a criminal record, which would lead him to relapse to his old lifestyle just to pay the bills.

Unfortunately, Alvarez and other ex-convicts may have legitimate cause for concern. Employers willing to hire ex-convicts are few and far between, and it is especially difficult for ex-convicts to stay out of prison if they’re released during difficult economic times like our current recession.

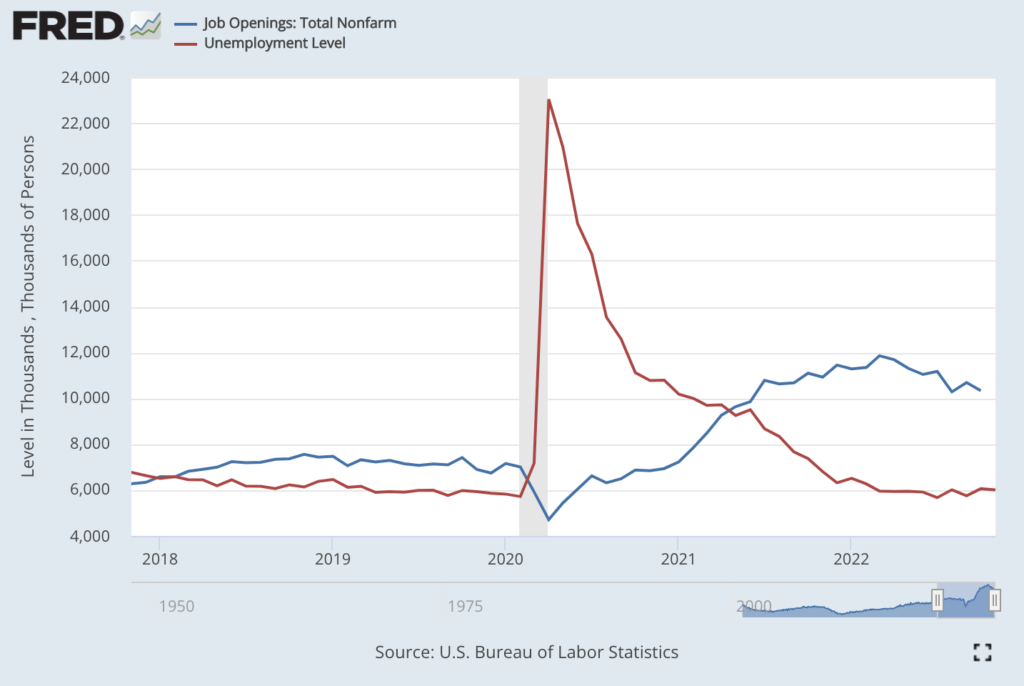

At the same time, labor shortages continue to plague the nation, almost three years after the pandemic began. As of October 31st, 2022, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics data showed that the US has over 10 million job openings, but only around 6 million unemployed workers. Part of the shortage can be accounted for by early retirees from COVID, some from COVID-related immigration shortages, but a large part is from frictional unemployment—many people who are looking for new, higher paying or more accommodating jobs in what some have termed the “Great Renegotiation.” While there isn’t one cultural shift to blame, it is clear that the pandemic caused many to re-evaluate their careers, family arrangements, and retirement plans. This shift has been detrimental to many businesses.

An underused program could help solve both problems. It can match ex-convicts with jobs, provide a new pool of talent for employers, and help boost the post-COVID economy.

Beginning almost 60 years ago, the Federal Bonding Program (FBP) incentivizes businesses to hire ex-convicts or others with “significant barriers to securing… employment.” The program provides six months of free insurance ($5,000–$25,000) to companies that hire ex-convicts, protecting them against financial harm that could result from employee dishonesty like theft, forgery, larceny, or embezzlement on or off the worksite.

And it’s remarkably simple. According to the program’s website, it requires:

- No application for job seekers to complete.

- No papers for employers to submit or sign.

- No formal bond approval process.

Those seeking employment simply register with their local state bonding coordinator, and a bond is issued upon employment. As of 2013, the FBP boasted a 99 percent success rate, meaning only 1 percent of employees proved to be dishonest on the job, causing the insurance to be paid out to employers. Even with the high success rate, the Federal Bonding Program is strikingly underutilized. Only 458 people were federally bonded in 2020 compared to around 650,000 people released from prisons each year.

These are people who need jobs badly, and an employment opportunity may be nothing short of life-changing.

With the FBP’s apparent efficiency and potential for societal impacts, policymakers should look for ways to better utilize and scale up this program to reduce poverty and recidivism among ex-convicts, while also boosting the economy.

The Challenge for Ex-Convicts

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, around 68 percent of people released from prison are rearrested within three years. That enormous recidivism rate costs hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars per case and disrupts countless lives. And while there are many ways to earn a criminal record, there is one main predictor of re-offending: poverty.

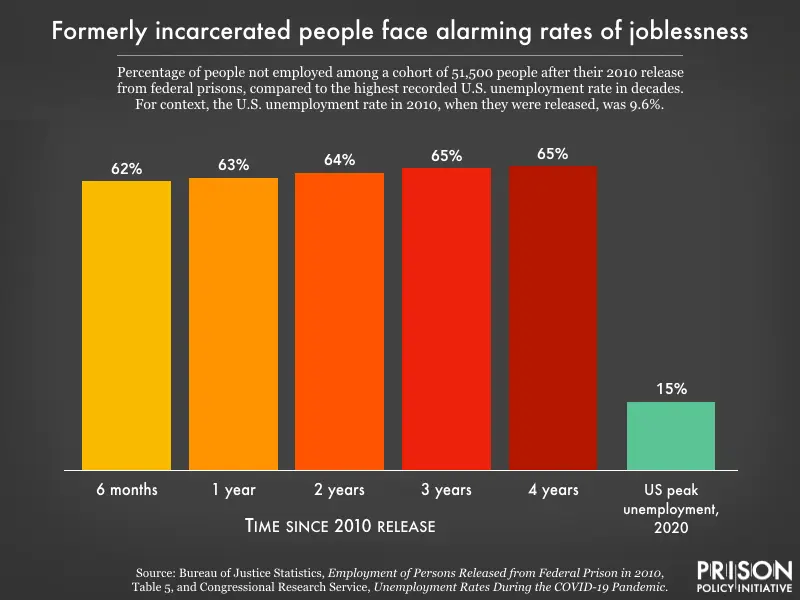

Escaping poverty can be difficult for ex-convicts. In fact, unemployment is up to five times higher for formerly incarcerated people, some of the people who need stable income the most. Many employers are hesitant to even consider applicants with a mark on their record, no matter how small. Repeated rejection from jobs can be discouraging, even immobilizing. Of course, many recently released people also struggle with housing instability, mental health issues, and lack of support from friends or family. With such a heap of social and financial barriers, poverty may feel inevitable, and ending up back in jail may feel difficult to avoid.

Expanding the Bonding Program Could Benefit Employers

The Federal Bonding Program encourages businesses to take a second look at these job candidates, many of whom are desperate for income and a chance to live an honest life. While ex-convicts benefit, employers gain from hiring ex-convicts as well. To begin, those with criminal records make up a highly under-utilized talent pool. These people could fill open positions that employers are searching to staff. The program may be especially beneficial for employers in food services or manufacturing—two sectors currently struggling with shortages.

Though it is harder for people with criminal records to find jobs, one study shows that they may stay longer at jobs once they have them. The authors of the study conclude that hiring ex-convicts represents a promising opportunity that “makes sense on both efficiency and on moral grounds.” For employers where turnover is a central driver for labor costs, giving those with criminal records a second chance may be particularly valuable.

In addition to closing a labor gap, the bonding program also insulates employers from risk. Current experience with the FBP gives little reason to worry that employers will be taken advantage of by their employees with criminal records. Still, with federal bonding, the first six months of employment are insured. That’s long enough to assess an employee’s fit and work ethic while protecting employers from risks.

Benefits to Taxpayers

But is federal bonding economically efficient considering the costs and payoffs? Unfortunately, due to the lack of knowledge about and data on the program, there isn’t much research done in this area. However, with low upkeep costs due to the simplicity of the program, and only a 1 percent rate at which the program has historically paid out insurance (up to $25,000), it should be remarkably effective with tax-payer dollars.

This is especially the case when compared to the approximately $47,000 dollars a year spent housing a single prisoner. Even if the FBP increases the rate of insurance payouts made to businesses in the future, keeping even a small number of people out of jail and reducing their reliance on welfare could easily make up the difference in government spending. After all, the current norm of reimprisoning two out of three ex-convicts is expensive and ineffective. Further utilizing the FBP could help mitigate some of the cost of recidivism.

As a report from the conservative American Action Forum concludes, “The high rates of recidivism indicate imprisonment does not deter future crime nor rehabilitate offenders.” However, providing a way for these people to change, contribute to society, and build a life away from poverty and imprisonment could certainly help with rehabilitation and reduce government spending.

Moving Forward: Raising Awareness, Gathering Data, and Potential Expansion

So where is the disconnect? Why is this program utilized so little? It’s simple and free for both employers and those seeking employment. Perhaps employers have other concerns and reasoning.

Some jobs, like most government positions, are legally prohibited for ex-convicts. Some employers may be concerned about high turnover rates or poor job performance (which aren’t covered by bonding). No major research or surveys have been done on employers’ hesitance to use the Federal Bonding Program. As for those seeking employment, perhaps ex-convicts wonder about how persuasive bonding is for employers, or maybe their applications are immediately dismissed before they can show they are federally bonded. Most importantly, maybe employers and prospective employees don’t know about the program and its simplicity.

With a 99% success rate in the past, expanding the Federal Bonding Program could reduce poverty and recidivism, while increasing the labor supply and cutting government spending on imprisonments. All this would contribute to more functional, happy communities and stronger economies. Expanding the program could take many forms—awarding more grants to state employment departments or even compensating employers for federally bonded workers’ job training. This could reduce the potential costs for employers who fear a high turnover rate with ex-convicts. Even relatively costly ways of expanding the program could reduce recidivism and therefore tax dollars spent on prisoners. Policymakers should experiment with these programs and invest in the most promising ones.

Most importantly, both employers and those with criminal records need to know about and understand the FBP. Each state’s bonding coordinators, the Department of Workforce Services, non-profits, and others need to raise awareness about the program, thereby increasing the amount of data on the FBP and better informing decisions about changing/expanding the program. Currently, many employers require information on an applicant’s criminal record on the very first stage of an application. However, increasing awareness of the benefits and success of this simple program may convince employers to take a closer look at those applicants, especially with current labor shortages. And as for those with criminal records, educating them about the program before release from prison could give them an invaluable tool to escape poverty.

While the Federal Bonding Program doesn’t exactly teach a person to fish, providing education and access to the Federal Bonding Program equips men and women with fishing poles. It gives them the tools and opportunities to learn and create a better life moving forward. And the benefits reach far beyond those individuals. It allows well-meaning people, like Gerald Alvarez, to change, put their past behind them, and become meaningful contributors in their families, workplaces, and communities.