The current government shutdown is now the longest in U.S. history. Because of its length, it’s also turning out to be more painful than any other before it, and government employees face the prospect of a second missed paycheck. And while the government shutdown has exposed that many are unprepared for financial shocks, either economic or political, it has exposed other weaknesses in how we govern. Specifically, increased partisanship has created a propensity for governing by shutdown. This has led to an environment in which the national parks have become a political bargaining chip to be played rather than a public treasure to be enjoyed by all.

The current shutdown’s impact on national parks is notable for a number of reasons. In contrast to previous shutdowns, about 80 parks remain open for visitors even as a compromise on the budget in DC appears unlikely and the National Park Service goes unfunded. Only a fifth of the staff, 4,000 of the approximate 20,000 usually monitoring the parks and assisting visitors, were working.

Without the staff to keep up with it, trash quickly piled up at the open parks. And, with public pressure mounting, the Trump administration allowed park managers to use park entrance fees to be used for maintenance and cleaning. P. Daniel Smith, the Deputy Director of the National Park Service, said:

As the lapse in appropriations continues, it has become clear that highly visited parks with limited staff have urgent needs that cannot be addressed solely through the generosity of our partners… After consultation with the Office of the Solicitor at the Department of the Interior, it has been determined that [entrance fee] funds can and should be used to provide immediate assistance and services to highly visited parks during the lapse in appropriations. We are taking this extraordinary step to ensure that parks are protected, and that visitors can continue to access parks with limited basic services.

The Administration’s move, which could stymie what may be long-term damage to parks, has been quite controversial across the political spectrum. Democratic members of Congress are questioning the current use of fees and during the January 2018 shutdown, former Department of Interior (DOI) Secretary Ryan Zinke said such fee use was illegal.

The legality of using fees is certainly an interesting question generated by the shutdown. However, a more important question should be focused on a long-term solution: How do we remove (or at the very least insulate) our national parks from political fights in DC?

Outside of the legal arguments, there are good reasons why we should be letting parks control more of the fees they collect.

But if we aren’t running them on entrance fees, then how are parks funded?

If you’ve been to many national parks, it may be surprising to find out that your fees weren’t already supporting park maintenance. Park funding is mainly appropriated from discretionary funding from Congress. As public lands policy expert Reed Watson testified in 2017, based on his analysis of federal data, “approximately 12 percent of the National Park Service’s annual budget comes from user fees and donations.” This means that Congress decides just under 90 percent of the NPS budget on an annual basis.

In recent years, those discretionary appropriations have been declining, after adjusting for inflation, since 2009. Funding is about eight percent lower in 2018 than it was in 2009, according to the Congressional Research Service’s natural resources policy specialist, Laura B. Comay.

NPS Congressional Appropriations (FY2009 — FY2018)

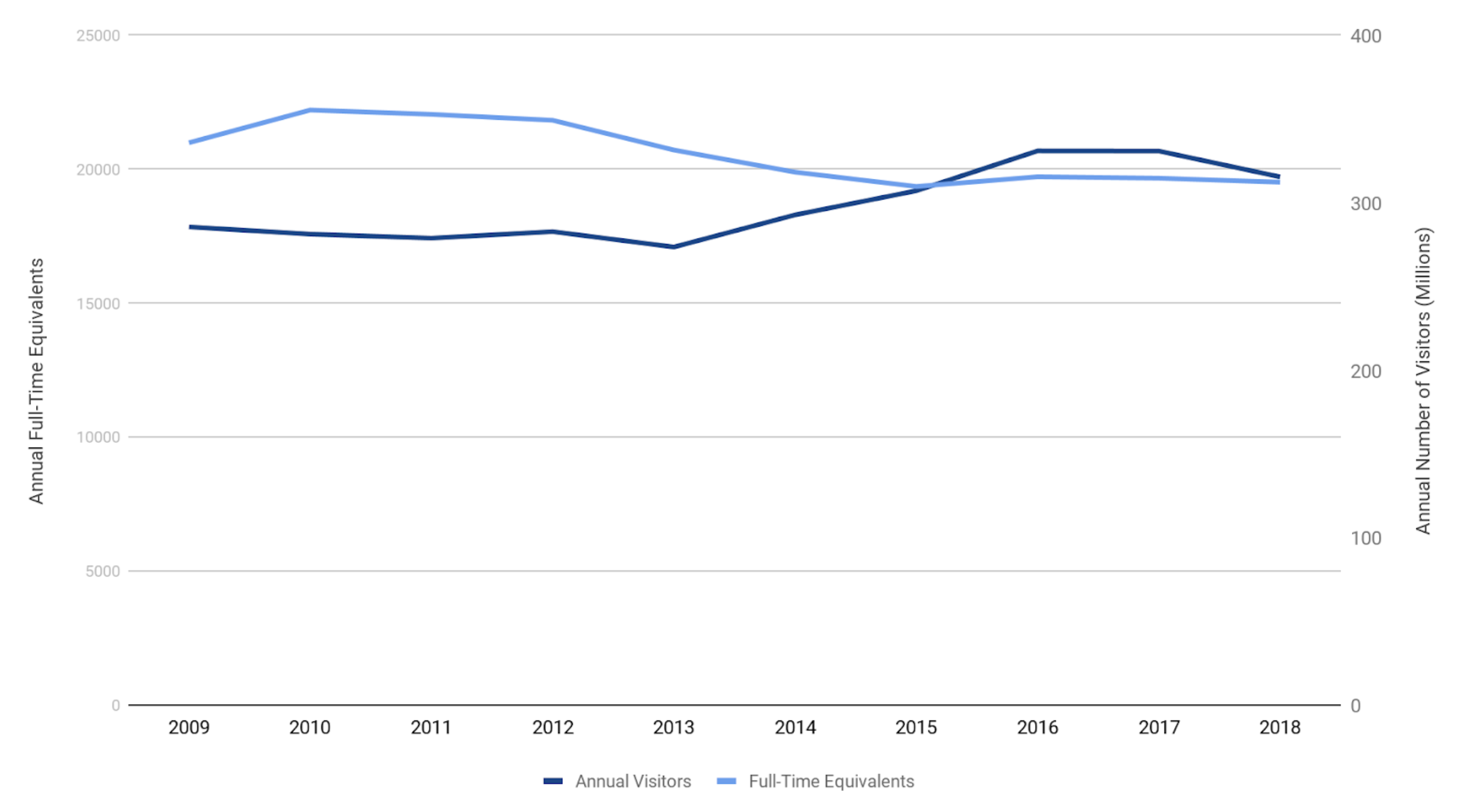

And, relative to visitation, which is hitting record highs, funding is declining more rapidly. What complicates this further is the falling staffing levels at the NPS. Not only is the number of visitors to national parks rising, but the number of workers available to staff those parks is also shrinking.

Park Service FTEs v. National Park Visitors (Annually)

Data note: Congressional Research Service and author’s calculations. To calculate 2018 numbers, which have not been released yet, I took the average visitation rates from 2014 through 2017.

Data note: Congressional Research Service and author’s calculations. To calculate 2018 numbers, which have not been released yet, I took the average visitation rates from 2014 through 2017.The issue of Congressional appropriations can be put in better perspective when compared against the maintenance backlog. The NPS currently needs about four times the amount appropriated in 2018 just to do all the necessary repairs and maintenance projects it believes are necessary. A 2016 government report put the costs of the needed maintenance at $11.3 billion.

In a 2018 interview, John Garder of the National Parks Conservation Association has pointed out, “As a general rule, parks are underfunded. The two main issues are understaffing and the deferred maintenance backlog.”

Garder’s complaint isn’t new. The data in the charts above seem to suggest that he’s correct. But so do past comments by the Government Accountability Office and National Park Service staff. In 2003, the Government Accountability Office testified that the NPS could not run their current parks on the budgets they were allotted without risking damages to the park or further increasing the maintenance backlog.

For example, J. T. Reynolds, the superintendent of Death Valley National Park, requested that the government stop making additional parks without increasing their budgets or at least only add new parks only when truly necessary, when the land needed immediate protection, for example. Reynolds testified:

The Administration is committed to taking better care of what we have, while ensuring that new acquisitions truly meet strategic needs of the NPS. There must be a balance between acquiring new lands and meeting the operational, maintenance, and restoration requirements for the resources already in public ownership. In keeping with this priority and other priorities such as improving security at our parks, we have often opposed, or asked for the deferral of action on, legislation introduced in Congress that would create new park units or expand existing parks.

At the same hearing, Barry T. Hill, the General Accounting Office’s Natural Resources and Environment Director, testified to the same effect. When asked about the government acquiring new lands for the NPS, Hill testified:

I definitely think that those costs need to be identified, here again, both the operating and the maintenance costs need to be line itemed and, basically, Congress needs to be aware of those costs. Right now, the land is acquired and those costs are not really fully understood, and then the Park Service, basically, has to absorb those costs, and it really strains the entire system.

As Hill went on to explain, that doesn’t mean acquisitions should halt where lands worth protecting exist. It does mean, however, that additional funding is necessary to protect additional lands given to the NPS. In the face of rising visitation rates and fewer staff members at parks, these concerns from 2003 still exist today.

With the passage of the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act (FLREA) in 2004, at least 80% of the fees collected by parks remain in the parks. The other 20% is allocated by the NPS. This was a change from the previous practice of sending fees to the US Treasury and ensures that parks retain some of what they contribute to enhance the parks for future visitors. Even with this influx of fees over the past 15 years, that money is restricted. Park fees may only be used by park managers to make improvements that will enhance the visitor experience. As a result, the current debate about how the NPS uses park fees sparked during the government shutdown is really about whether or not cleaning up the trash and restroom facilities at the parks is an “enhancing” visitor use of the park fees.

Can we make parks nonpartisan?

Two changes can make the NPS less susceptible to DC’s partisan gridlock:

- First, give more authority to local park managers. This could be done by redefining the “enhancing” term in FLREA to be at the discretion of park managers, for example.

- Second, encourage the NPS to experiment with public-private partnerships. Both the Forest Service and California have experimented with private management of publicly owned parks, with great success for conservation goals.

Give more authority to park managers

Those closest to the parks likely have the best knowledge about problems that those parks face. Freeing park funds from the one-size-fits-all model and devolving authority to park managers to make the decisions about where collected fees ought to be invested would empower those people with the necessary knowledge to run and protect their park.

One additional part of devolving control should be giving park managers the authority to set their own pricing. Currently, many parks suffer from overcrowding. The overcrowding isn’t a constant problem, however. Instead, there are peak seasons where parks are busier than normal. This suggests that at least some of the year, park fees are underpriced. Letting parks charge more on months or days where there is unusually high demand could help them manage the overcrowding and raise additional revenue. Dynamic pricing could also go a long way toward mitigating damage due to the landscape caused by overcrowding.

Letting park managers change the fees they charge may price some people out of national parks at the most in-demand times of the year. But the other side of dynamic pricing is that park staff could also set prices lower in months where they think demand may not be as high, or managers could even price certain times of the year at zero.

Devolving decision-making powers to those on the front lines at parks creates a tighter feedback loop between visitor rates and fee revenues. Yes, fees at some point will be higher. But at other times they’ll also be lower. Moreover, the park managers can respond to the feedback loop fee changes create. Many may choose to stick with their current fee levels, but under this policy change, it would be their choice. And, in summer months when they expect people to be willing to pay more for entrance, they can choose to bring in extra revenue to deal with the backlog of repairs.

It is worth noting that fees alone will not support the parks. That 12% of parks are funded by user fees is encouraging, but that leaves 88% to make up. Many park areas don’t assess an entrance fee at all. The NPS controls 418 areas. Only one out of four of those charges an entrance fee. Even in the 115 parks that charge for entrance, fees are low. Fees range from around $10 to $35 per vehicle and are set according to a standardized fee structure that the NPS created in 2014.

While it is true that fees alone won’t cover that gap, allowing park managers to both change fees and determine their best use within a park could insulate parks from the effects of shutdowns in the future. In short, Congress could give managers the ability to plan around periods when appropriations aren’t forthcoming or consistent.

Consider a hypothetical future shutdown that stops appropriations just as the current shutdown has done. A park manager with expanded authority over fees and park management could decide to set fees at whatever level she needs to continue operations. Without public funding for the park lowering the cost of entrance, that’s likely to be four or five times their levels today, but it could be what is necessary to prevent long-term harm to the park. With expanded authority, the manager could then use entrance fees to pay for staffing during future shutdowns.

Why is this so important? Several reports surfaced of vandalism at Joshua Tree National Park in early January. With authority to use park fees as they believe necessary, managers could staff parks, even if only at a skeleton level, to prevent long-term damages like the tree-felling at Joshua.

Joshua Tree is a good example of the problem with limiting the uses of park fees. Although it was going to remain open during the shutdown to stay open until the vandalism and overflowing toilets spurred a plan to close the park. However, once the NPS announced the policy of allowing managers to use park fees, the decision was made to keep the park open. The long-term environmental damage being done to the parks as a result of the government shutdown could have been avoided altogether (or at the very least greatly minimized) by simply giving park managers the authority to use fees in as they see fit in the first place.

Protect Parks With Public-Private Partnerships

Another way to insulate parks from political gridlock is to experiment with public-private partnerships. California, for example, uses private organizations to manage several of the state’s parks. The impetus for California’s experiment is not that different from our current situation. Facing several state parks due to close because of budget shortfalls, the state decided that privately managed parks were better than closures.

Limekiln State Park, one of California’s privately managed public parks. Photo Credit: “Limekiln State Park” by Kevin Stanchfield is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Limekiln State Park, one of California’s privately managed public parks. Photo Credit: “Limekiln State Park” by Kevin Stanchfield is licensed under CC BY 2.0.There’s clearly an appetite for these same arrangements with national parks. Consider how private businesses that rely on parks like Yellowstone reacted when the parks closed. A snowmobiling company in the Yellowstone area now employs furloughed park service employees and pays around $7,500 each day to clear the roads and maintain the trails that the snowmobiling tours use. Private companies help complement the amenities offered in national parks and already face an incentive to help keep parks open. The NPS could take advantage of these incentives by experimenting with private partnerships as the Forest Service has done for decades.

Conclusion

The $11 billion maintenance backlog should be reason enough to drastically rethink how we fund the National Park Service and that changes in park management policy are badly needed. However, the mistreatment parks have received as a result of being played as a political bargaining chip should be a greater cause for concern.

It has been said, after all, that the national parks “reflect us at our best.” Government shutdowns, it could be said, reflect us at our worst.

We should ensure that the parks are protected for future generations, and those who spend their days running them are the people most likely to accomplish that goal. What I’ve outlined above is one promising opportunity to make sure our parks are now swept up in the beltway bickering of the future.

Congress is already on a shot clock to ensure an orderly future for the NPS. FLREA, the act that allows parks to keep 80% of fees they raised, will expire in September. To at least maintain the status quo, Congress must act in the next seven months. It could, however, take the opportunity to institute greater protections for our national parks. As former park ranger Shawn Regan pointed out, “if we truly want to protect our national parks, we need to find ways to protect them from Washington.”