Much has been written about the growth of the gig economy, and many have tried to estimate just how fast it’s growing. In 2016, economists Lawrence Katz and Alan Krueger released research showing that the percentage of the American workforce made up of alternative work arrangements had grown by more than 50 percent. Katz and Krueger found that from 2005 to 2015, the percentage of workers engaged as “temporary help agency workers, on-call workers, contract workers, and independent contractors or freelancers” rose from 10.1 to 15.8 percent. Other studies have found that there has been significant growth in gig work since 2000 (measured by 1099-MISC forms issued by the IRS) versus traditional work arrangements (W-2 forms) over the same period.

The data seem to suggest that we are experiencing a massive shift in how people are working. Maybe.

Last summer, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released new data on “contingent and alternative employment arrangements” that suggested the gig economy may actually be shrinking. According to the BLS, the proportion of the American workforce engaged in alternative work arrangements actually fell slightly, from 10.7% of all workers in 2005 to 10.1% in 2017.

What should we make of these dramatically different findings? Have we seen the end of the gig economy?

The reports of its death are greatly exaggerated

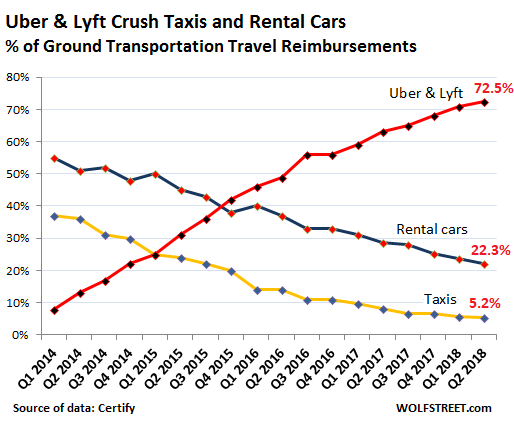

Taken at face value, the BLS data seems to suggest that the number of people working in alternative work has been declining even as Uber, Lyft, Thumbtack, TaskRabbit, and many other platforms have entered the market.

If you think this seems strange, we agree. And there are some reasons to doubt that the BLS’s findings truly signal a decline in the gig economy.

First, the questions regarding contingent work arrangements only capture those that use them as a primary source of income. According to the BLS, “Questions on contingent work and alternative employment arrangements are only asked about a person’s main job.” This means that anyone with a traditional W-2 job who also works after-hours for Uber or does freelance work on weekends isn’t counted in the data. The survey also failed to include anyone that did freelance work less frequently than every week, despite the fact that many freelancers engage in this type of work much less frequently.

Second, as Dourado and Koopman (2015) pointed out:

The more flexible work arrangements offered by sharing-economy platforms provide an alternative for those excluded from traditional employment relationships. The rise of firms such as Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, Instacart, and others should be seen as the product rather than the cause of the growing 1099 workforce. These companies are able to offer employment on these more flexible terms only because there is a willing supply of workers eager to accept them.

In short, we should expect to see increased numbers of workers in non-traditional arrangements in a weaker labor market and decreased numbers when the labor market is stronger. The BLS numbers may simply be capturing differences in the labor market between 2005 and 2017.

Regardless of what the BLS data may suggest, many other estimates of the gig economy suggest it is alive and well. The Federal Reserve released its own report last summer which found that 31 percent of US adults participated in the gig economy in 2017, most of them to supplement income from a full-time job. Likewise, in 2016, the McKinsey Global Institute found that independent workers make up between 20–30 percent of workers, while Upwork estimates that number to be even higher, at 36 percent of the workforce.

All of these data points suggest the gig economy isn’t going anywhere.

How workers benefit from the gig economy

So, if the gig economy is here to stay, it’s time we should start thinking deeply about where the benefits of these changes will fall. Specifically, who benefits from this continued growth in the gig economy? Short answer: everyone.

Here’s the reality of it. Everyone will be impacted. The impacts will be felt in different ways. Everyone will benefit in some way, but some will see larger benefits than others. Yes, some will lose in the short run. However, history suggests that the long-run benefits will be far greater.

Most obviously, employees participating in the gig economy benefit from increased flexibility, the ability to choose projects that best align with their goals and interests, and the ability to earn income from multiple sources. While freelancers tend to worry about income predictability (and dip into their savings more often), a recent report from Upwork suggests that nearly two-thirds of freelancers think that having a diverse set of income sources is more secure than relying on one employer.

Of course, this is not to say all is rosy for those making their way in the gig economy. Talking briefly about a different type of benefits (i.e., nonwage compensation) that we’ve come to expect from employment, the gig economy turns much of this on its head. As a byproduct of historical events, the traditional employer-employee relationship has become the primary vehicle for delivering health insurance to workers in the United States. Because participants in the gig economy are working full-time for one specific employer, many contractors and freelancers are left without employer-sponsored health insurance, employer-financed retirement plans, and paid time off.

One option is to offer these workers portable benefits that would help pick up the slack. According to the Aspen Institute, portable benefits are categorized by three characteristics:

- Portable: workers’ benefits are not tied to any particular job or company; they own their own benefits.

- Pro-rated: each company contributes to a worker’s benefits at a fixed rate depending on how much he or she works or earns.

- Universal: benefits cover independent workers, not just traditional employees.

There is some evidence that companies are popping up already to help meet this growing need. For example, Trupo offers disability insurance on a sliding scale with contracts that can easily be revamped from month to month depending on the needs and ability of gig workers to pay. Another example is Alia, which was created by the National Domestic Workers Alliance to allow employers to choose to add $5 on top of each house cleaning fee they pay to help workers pay for a range of benefits.

Companies like Lyft and Uber have also stepped up to provide perks and rewards to drivers. Lyft, for example, offers discounts for accessing telemedicine, fuel discounts and roadside assistance. Uber subsidizes car maintenance and discounts on phone plans. Both companies offer services to help drivers find health insurance.

Conversations about portable benefits solutions are sure to continue, especially surrounding whether these benefits should be reliant on the goodwill of employers or determined by some sort of government mandate.

How companies are leveraging the gig economy

A large part of the cost of an employee comes in the form of benefits. So one obvious benefit to employers is saving on these costs by contracting rather than employing workers. They can also avoid the costs associated with hiring, including interviewing and the risk that they may be making a big investment in talent that won’t fit well in the long term. Instead, companies can engage with the right people with the right skills for today’s project, without having to worry about the long-term fit.

It may also dramatically change how we think about how companies are arranged altogether. As Michael Munger has explained:

Firms may rent capital equipment and labour for very short periods, increasing the productivity of the workers for the period that they are employed and dramatically reducing the fixed costs of the firm. In the limit, firms themselves might simply become individuals or small teams that hire out for specific projects. Workers in this system would be private contractors, not ‘employees’ in the traditional sense.

And what about traditional employees?

Although they may face new competition in a dramatically changing labor market, workers in traditional employment arrangement may see benefits from the growing gig economy. As the workplace continues to change, more and more employees are demanding more flexible work arrangements that give them more control over where and when they work. Employers are responding to this pressure by allowing more employees to work remotely.

According to a survey by Gallup, in 2016 43 percent of Americans spent at least some time working remotely — an increase of four percentage points since 2012. Gallup found that a company’s policies on remote work and flexible scheduling have a big impact on their competitiveness for job candidates:

“Gallup consistently has found that flexible scheduling and work-from-home opportunities play a major role in an employee’s decision to take or leave a job.”

Conclusion

Ultimately, the result of the growing gig economy will be increased competition on multiple margins. Overall, that’s a good thing. Growing competition for flexible and meaningful jobs is driving workers to reassess their abilities and retrain. Growing competition for quality employees is driving employers to offer more flexible work arrangements and to give their employees more autonomy over their own schedules. And, of course, competition for customers is improving the consumer experience across a wide range of services from food delivery to transportation.

As the gig economy continues to grow, we should ensure that the public policies that shape it foster continued innovation and entrepreneurship. If we are successful, we will find a future with increased flexibility, choice, and greater opportunity for tomorrow’s workforce.