Our attempt to explore the issue of poverty starts with the recognition that poverty has been the typical state for most human beings throughout human history. It is only in the past 200 years or so that more than a tiny fraction of human beings have been able to live long lives of material and physical comfort. In some sense, the intellectual puzzle of human economic history is not explaining the causes of poverty, but the causes of the much more exceptional wealth of the modern era. Put differently, how did humans ever escape a world where nature-given resources cannot possibly enable more than a small number of people to survive at a subsistence level? What are the causes of what economic historian Deirdre McCloskey calls “the Great Enrichment?”1Deirdre N. McCloskey, The Bourgeois Virtues (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

Even as the Great Enrichment has raised living standards in the Western world and lifted billions out of severe poverty across the globe in the past few decades, poverty still exists in multiple forms worldwide. In the West, there are still too many people who have not been able to share fully in the cornucopia of the Great Enrichment. Nonwhite households are more likely to be persistently below the Western poverty line, even as others move up and down the income ladder. In the rest of the world, especially in Africa, too many households, and whole countries, have not been able to escape to anything close to Western levels of material comfort, even where they aspire to that goal and are willing to work for it. In the West, we see household-level poverty in the midst of societies that have great riches, while elsewhere we see both household- and country-level poverty in the midst of increasing worldwide plenty.

The task of this chapter is to offer some insight about these two outcomes. If the Great Enrichment has done so much for the West and is starting to do the same elsewhere, why has it not spread to all in the West, and why have so many elsewhere in the world not shared in its benefits? The answer we will propose is that the freedom to trade in the marketplace and the ethical approval of such activity, both of which were crucial to the Great Enrichment, have been restricted through government regulations in ways that perpetuate poverty. In the Western world, these regulations affect entry-level labor markets and the entrepreneurship associated with new small businesses, thereby making it more difficult for lower-skilled workers to rise out of poverty. In many other parts of the world, the regulatory state is more encompassing, making it very difficult for most citizens, and not just the poor within those countries, to start new businesses and to operate in an environment of generalized freedom to trade. In both parts of the world, these regulations restrict what has been termed the “permissionless innovation” necessary to reap the benefits of the discovery process of competitive markets. The more often that people need permission from government regulators to try out new ideas or to tweak earlier innovations, the more difficult it is to create the wealth that raises living standards and pushes back against poverty.

The next section explores in greater detail the question of how the West grew rich and why that Great Enrichment has not fully spread elsewhere. Understanding who benefits from regulation is crucial to providing that answer. The two following sections provide examples from the US and Senegal of the way restricting trade and requiring permission to innovate has perpetuated the pockets of poverty in the West and the more widespread poverty in other parts of the world.2We have chosen Senegal because one of the authors (Wade) is Senegalese and spends considerable time in Senegal, where she operates a business. The potential for bringing the benefits of the Great Enrichment to all the world is real, if only we can identify the regulations that prevent economic growth and upward mobility and then remove them and allow markets and competition to spread the Great Enrichment globally.

Trade and the Great Enrichment

The facts of the Great Enrichment are well known and largely uncontroversial. In the 19th century, a significant and growing portion of humanity began to escape the grinding poverty that had characterized human history up to that point. Although in earlier times a small portion of the privileged, such as royalty, had lived comparably well, even the quality of their lives paled in comparison to what the Great Enrichment would bring. One of the great accomplishments of the past 200 years has been the rise in the living standards of more and more ordinary people. It may well be true that the rich today live incredibly well, but the average westerner lives far better than the kings and queens of old—even the average African outdoes them. One need only consider that approximately 80 percent of adult sub-Saharan Africans own either a basic cell phone or a smartphone.3Laura Silver and Courtney Johnson, “Internet Connectivity Seen as Having Positive Impact on Life in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Pew Research Center, October 9, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/10/09/internet-connectivity-seen-as-having-positive-impact-on-life-in-sub-saharan-africa/.

More generally, we can follow McCloskey’s calculation that the average human now consumes 8.5 times more than the average human 200 years ago and lives twice as long (after making it to age 16), and that the earth is able to support 7 billion people as opposed to 1 billion.4McCloskey, The Bourgeois Virtues. (We have updated the world population number from 6 billion to 7 billion.) If we do the multiplication (8.5 × 2 × 7), the result is that humanity is 119 times better off, in terms of total consumption by the total number of human life-years, than 200 years ago. There are now more people living longer lives with more ability to consume, and by a factor of 119.5Note that this is a factor of 119, not 119 percent. In percentage terms, we are 11,900 percent better off in terms of total quality of adult years.

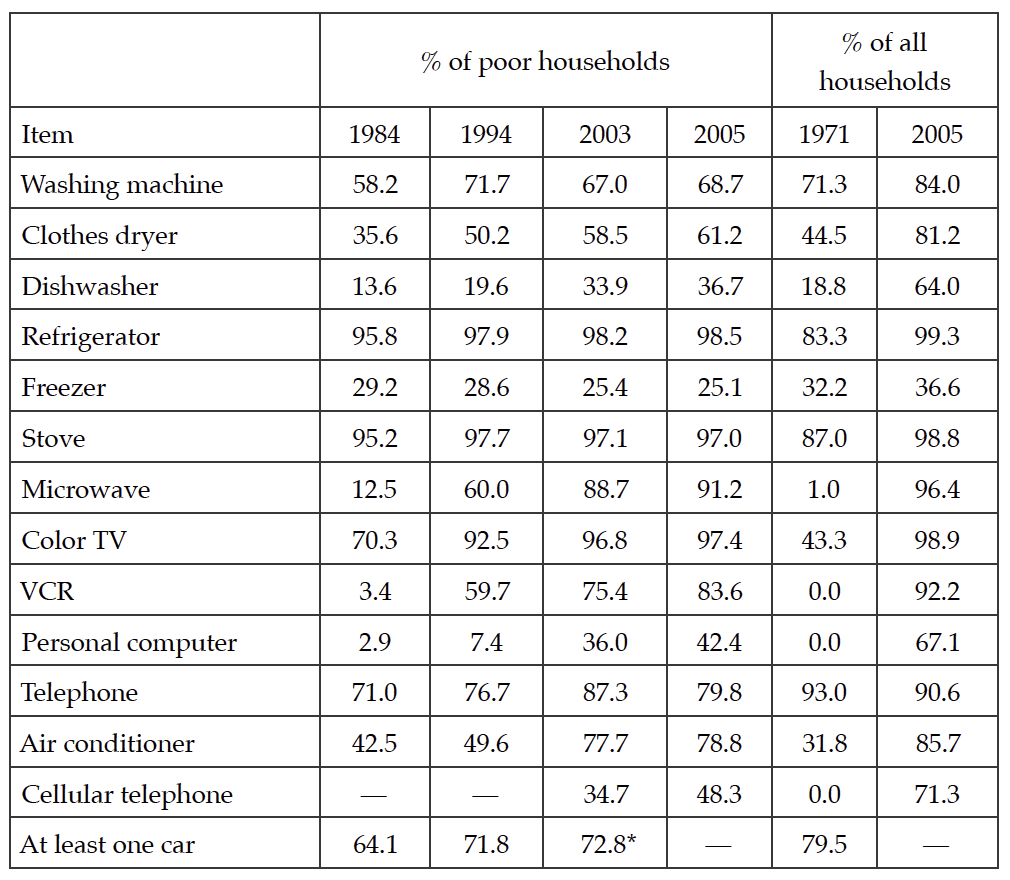

We have seen the effects of this enrichment in the United States and globally. Of course a comparison between 2019 and 100 or 200 years prior would clearly show those gains in wealth, but one number is worth considering: the percentage of income spent on food, clothing, and shelter has fallen over the past 100 years, from about 75 percent to 35 percent.6All the statistics in this paragraph are from Steven Horwitz, “Inequality, Mobility, and Being Poor in America,” Social Philosophy and Policy 31, no. 2 (Spring 2015): 70–91 and the references therein. The value of labor has climbed and market competition has kept prices affordable, with the result that members of the average US household today have a great deal more discretionary income than their grandparents and great-grandparents did. Even if we look at the past 50 years, we can see that the percentage of US households that possess basic appliances such as washing machines, dishwashers, and dryers, as well as goods such as TVs, air conditioning, and microwaves, has increased, in some cases substantially (see table 1). In addition, average (and poor) US households have goods that didn’t even exist 50 years ago, such as smartphones, personal computers, and other electronics, not to mention access to new lifesaving drugs and other medical treatments. Economist Michael Cox and economic journalist Richard Alm provide a useful nice list of items available at the end of the 20th century that did not exist a generation earlier.7W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm, Myths of Rich and Poor: Why We’re Better Off Than We Think (New York: Basic Books, 1999). This standard of living should be, but is not always, available to all Americans, and finding ways enable more people to enjoy that standard is the problem that needs to be addressed.

Table 1. Percentage of Households with Various Consumer Items, 1971–2005

* This number is for 2001.

Source: US Census Bureau, “Extended Measures of Well-being: Living Conditions in the United States, 2005,” 2005, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2005/demo/well-being/2005-tables.html.

Figure 1. Changes in Global Poverty, 1990–2013

Source: http://ourworldindata.org/extreme-poverty, using data from World Bank, “PovcalNet: An Online Analysis Tool for Global Poverty Monitoring,” http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/. Accessed September 17, 2020.Globally, one of the unheralded stories of the past few decades has been the enormous decline in extreme poverty. We have seen the rise of global consumption as more and more people across the world have begun to approach Western standards of living. Less obvious has been the decline of extreme poverty. The World Bank reports that the percentage of people living in extreme poverty, defined as less than $1.90 per day, fell to 10 percent in 2015, which is a historic low. The total number of people living on less than $1.90 day fell to 736 million. This represents an enormous decline over the past few decades, as more than 1 billion people moved out of extreme poverty between 1980 and 2015.. The World Bank estimated that the number for 2018 would be 8.6 percent of the world’s population below the extreme poverty line.8World Bank, “Decline of Global Extreme Poverty Continues but Has Slowed: World Bank,” press release, September 19, 2018, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/09/19/decline-of-global-extreme-poverty-continues-but-has-slowed-world-bank.

Despite these accomplishments, it remains the case that parts of the world have not had as much success as others. Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, is expected to have more than 10 percent of their population below the extreme poverty line for at least another decade.

To understand these data on the Great Enrichment, and why poverty persists in the midst of plenty, we need to understand the causes of the explosion in wealth of the past 200 years.9For documentation of the historical importance of the Industrial Revolution and the liberal institutions that made it possible see McCloskey, Bourgeois Virtues; Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990); Douglass C. North, Structure and Change in Economic History (New York: W.W. Norton, 1981). The key factors were the freedom to trade in markets and an ethical system that accepted, if not approved of, the innovation that markets produced and the profits that they generated.

More specifically, we might break the “freedom to trade in markets” into two pieces: the first is “permissionless innovation” and the second is “trade-tested betterment.” What happened in the early 19th century is that it became possible for more people to try out new ideas without having to obtain a license or other permission from governments. Rather than being seen as a threat to the established traditions, innovations became tolerated and encouraged as the risks of failure lessened thanks to more stability in agricultural output. The problem then became determining which innovations were truly beneficial and which were not. What McCloskey calls “trade-tested betterment” is the process by which the profit and loss generated through market exchange provides the test for whether particular innovations are sources of social improvement. Profits tell us that value has been created and that we are better off, while losses tell us that value has been destroyed and that we need to try something different.10On “permissionless innovation,” see Adam Thierer, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, rev. and exp. ed. (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2016), https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Thierer-Permissionless-revised.pdf. On “trade-tested betterment,” see Deirdre N. McCloskey, Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

Trade-tested betterment through the guide of profit and loss requires a number of other institutions. Having new ideas and inventions is not enough. The right institutions are necessary to turn inventions into innovations that improve people’s standard of living. First and foremost, there must be private property rights, and those rights must be clearly defined and effectively and fairly enforced. The wealth-creating processes of innovation and testing by profit and loss require that people know that their property is theirs and will remain theirs into the indefinite future. This means that it is protected from the predation of both other private actors and governments. State actions ranging from the uncompensated use of eminent domain to full nationalization (or the threat thereof) will discourage property owners from being willing to take the risks associated with innovation. So will regulations that impose excessive and unnecessary costs on potential producers.

Along with private property, these processes require the rule of law. The law must be clear and public and those who write and enforce the law must be subject to it as well. The rule of law also enables actors to form reliable expectations about the future and know that they will be treated fairly.

The last institutional requirement is sound money. All of the market transactions that drive economic progress take place in terms of money, and if money’s value is constantly fluctuating because of inflation or deflation, market exchange and the calculation of profit and loss are much more difficult. In such situations we will get less innovation and weaker market tests, leading to less wealth creation. The parts of the world that respect private property, adopt the rule of law, and have sound money have historically experienced the most widespread enrichment.

Alongside these institutional requirements, the Great Enrichment also requires that people have an ethical system that encourages the openness, innovation, and profit-seeking that is associated with market exchange. In McCloskey’s terms, our “habits of the lip” are at least as important as the institutional structures in which we operate. A society that has these institutions but also expresses strong disapproval of innovation or profit-making would have a hard time generating enrichment. In her work, McCloskey argues that changes in how entrepreneurial activity was perceived, along with an increasing tolerance for people striking out on their own and seeking their fortune rather than staying with family and community, were crucial to the Great Enrichment.11McCloskey, Bourgeois Equality. How people talked about trade, markets, and profits shifted in important ways, and the behavior associated with those institutions was increasingly seen as virtuous. That shift provided a necessary complement to the institutional requirements noted above. Together they produced the Great Enrichment.

To the degree that these institutional and ethical requirements are in place today in various countries around the world, those countries have continued to prosper. There is nothing in the story of the Great Enrichment that suggests that any group of people, be it an ethnic group or an entire nation, cannot share in its bounty. Adopting the right institutions and ethical perspective is what is needed, and this path is available to all humanity.

If we know what reduces poverty, why does it persist in pockets in the West and more broadly elsewhere in the world? Why haven’t the right institutions been adopted more consistently worldwide? There are a variety of answers to that question, but the overarching explanation is that the benefits of good institutions are widely dispersed across the population and are often subtle and slow to develop. This makes it hard for people to appreciate them, especially when regulation and intervention into markets has benefits for well-organized groups that can be part of creating them. The benefits from intervention and regulation are concentrated in the hands of a small number of people who therefore have an incentive to argue for regulation, while the costs in terms of lost overall growth are spread thinly across the whole population, and are often hidden and long-run, giving the larger population little incentive to oppose the regulation.

For example, when a group of producers argues for a regulation that will prevent others from entering their line of work, they stand to benefit significantly from it, while the costs in terms of higher prices, lower quality, and less innovation are spread across a much larger number of people and the per capita cost is quite small. Those with political power, or with the resources to access political power, will frequently have exactly this sort of incentive to favor regulation and the weakening of wealth-creating institutions, unless there are political safeguards in place to prevent them from doing so.12For a more complete development of this idea, see Mancur Olson, The Rise and Decline of Nations (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1982).

In some cases this dynamic takes the form of what is known as the “bootleggers and Baptists” problem.13Bruce Yandle, “Bootleggers and Baptists—the Education of a Regulatory Economist,” Regulation 7, no. 3 (1983): 12–16. Those who gain materially from regulation or from weak institutions often find themselves getting support from others who have a strong ideological or moral belief that a regulation is needed. For example, suppose a big-box store wants to open across the street from a shopping mall. The owners of the mall, and the owners of the stores that occupy it, might have many financial reasons to oppose the new big-box store. They stand to benefit from a regulation that would prevent such a store from opening. They are the “bootleggers” who benefit from preventing market exchange. They might find common cause with environmentalists who, while they have no financial interest in stopping the big-box store, have a strong commitment to making sure the new store does no environmental harm. They are the “Baptists” whose moral or ideological beliefs are satisfied by stopping the new store.

A good number of regulations give rise to this kind of alliance of strange bedfellows, making it more likely that they will pass, even if they are harmful in terms of overall economic well-being. The challenge for those seeking to generate consistent enrichment is finding ways to develop and preserve the wealth-enhancing institutions in the face of the incentives that well-organized interest groups have to lobby for regulatory interventions that benefit themselves at the expense of others or weaken wealth-enhancing institutions. Poverty exists where that challenge has not been overcome.

The Regressive Effects of Regulation in the United States

Most people assume that the purpose of regulating economic activity is to protect the most vulnerable people against the predation of those with economic power who often take advantage of what economists call “market failures.” We imagine that the primary effects of regulation are to restrain the activities of those who prevent consumers and smaller producers from surviving the competitive process. In that imagining, we forget that it’s not possible to regulate just one side of an exchange. All regulation, of necessity, limits the choices of both buyers and sellers. For example, if we pass a law that says employers cannot pay their workers less than $15 per hour, we are also passing a law that says workers cannot accept a job for less than $15 per hour, even if they might very much wish to do so. The same is true of regulations on producers, such as zoning laws. They do indeed limit the choices about where sellers can locate, but they also limit the options available to buyers in the areas sellers are prohibited from operating. Combining this point with the discussion in the previous section about the way some sellers can use regulation to raise the costs of their rivals and profit without improving the price or quality of their product, we cannot assume that regulation will always benefit the little guy.

Economist Diana Thomas describes a different pathway for the regressive effects of regulation.14Diana Thomas, “Regressive Effects of Regulation,” Public Choice 180 (2019): 1–10. If we view regulation as an attempt to manage perceived risks, we see that regulations often focus on low-probability risks that the relatively wealthy are unable, or simply do not wish, to manage themselves. If we imagine households both spending their own funds and lobbying for public expenditures to reduce risks, the costs of regulations that focus on low-probability risk will fall disproportionately on lower-income households. Thomas argues that these costs displace private household spending that might have served to mitigate higher-probability risks than those being regulated.

Thomas uses the example of mandating rear-view cameras in cars. Such regulations raise the cost of cars, including used ones, and they save very few lives. To the extent that these sorts of regulations reduce the disposable income of poorer households, they crowd out the expenditures such households would make to mitigate much higher-probability risks (e.g., spending on medical care). Wealthier households supporting such regulations are far less likely to be subject to that crowding-out effect. Thomas concludes, “Regulation has a regressive effect: It redistributes wealth from lower-income households to higher-income households by forcing lower-income households to subsidize the risk mitigation preferences of the wealthy and pay for risk reductions they would not otherwise choose.”15Thomas, “Regressive Effects of Regulation,” 5. Whether through the effects of limiting choice for consumers and rivals by lobbying for regulations, or through exploiting differences in the cost of risk mitigation, regulation benefits those with more resources more often than it does those with fewer.

Regulations designed to end poverty, for example, often end up promoting more poverty than they relieve. One example of this phenomenon is minimum-wage laws. From the employer’s perspective, minimum-wage laws are minimum-productivity laws. If I have to pay you $15 per hour, I’m only going to hire you if you produce at least $15 per hour of value for my firm. If your skills are such that you cannot produce that much, you will not be hired. Minimum-wage laws thereby cut off the bottom rungs of the economic ladder by making it impossible for lower-skilled workers to enter the labor market. As a result, not only do those lower-skilled workers not have the opportunity to earn an income to relieve their current poverty, they cannot obtain basic job skills, as well as good references, that would increase their productivity and enable them to climb the ladder out of poverty. Moving out of poverty in a sustainable way requires employment, and the empirical evidence, while not unanimous, generally shows that minimum-wage laws cause some degree of unemployment among those who need jobs the most.

Unsurprisingly, when negative effects on employment and income are found, they tend to be concentrated among younger workers and those with weaker educations and less human capital in general.16See the review of the literature by David Neumark and William Wascher, “Minimum Wages and Employment,” Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics 3, no. 1+2 (2007): 1–182. Historically, minimum-wage laws have often been supported by higher-productivity workers playing the role of bootleggers (partnered with the “Baptists” arguing for the supposed injustice of market wages) who correctly see such laws as shutting out lower-wage competition from the market. If it is illegal to hire someone willing to work for $10 per hour, I will be that much more likely to hire higher-productivity workers who can justify the $15 per hour I must pay them. The history of minimum-wage laws shows the ways in which wealthier, higher-wage workers supported such laws as a way to foreclose lower-wage competition, especially competition being offered by immigrants and people of color.17See the discussion in Thomas C. Leonard, Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016). Minimum-wage laws thereby perpetuate poverty among the lower-skilled, lower-wage groups.

Other regulations can affect wages in ways that disproportionately harm the least well-off. Economists James Bailey, Diana Thomas, and Joseph Anderson argue that regulation redistributes wealth from the poor to the rich by creating more high-paying job opportunities at the expense of lower-paying ones.18James B. Bailey, Diana W. Thomas, and Joseph R. Anderson, “Regressive Effects of Regulation on Wages,” Public Choice 180 (2019): 91–103. Specifically, they investigate whether an increased regulatory burden causes firms to have to bear more compliance costs by hiring more employees who are better compensated, such as lawyers and accountants. If it does, the effect may involve firms reallocating labor resources from lower-paying production jobs to higher-paying compliance-related jobs, thereby harming lower-wage workers relative to higher-wage ones. Bailey, Thomas, and Anderson find “some evidence that the costs associated with regulation lead to slower wage growth and that the burden is borne disproportionately by lower-wage workers.”19Bailey, Thomas, and Anderson, “Regressive Effects of Regulation,” 101. Even if lower-wage workers are not made absolutely worse off by increased regulation, their relative position is worsened, making the effects regressive.

Though inflation is not a regulation, strictly speaking, maintaining sound money is one of the keys to fostering widespread increases in wealth that improve the well-being of the least well-off. Inflation also has regressive effects. Inflation imposes “coping costs” (which are economically identical to the “compliance costs” of regulation) that necessitate new expenditures by firms in high-inflation environments.20Steven Horwitz, “The Costs of Inflation Revisited,” Review of Austrian Economics 16 (2003): 77–95. The costs of coping with inflation include a relative shift away from workers involved in direct production to those hired to cope with the effects of inflation. As with the compliance costs of regulation, this will mean hiring more accountants, financial experts, and lawyers relative to production workers. Because those jobs are higher-paying, we would expect to see the same regressive effects on real wages during inflation as we see from an increase in the regulatory burden on firms.

In addition their effects on wages directly, regulations can affect the quantity of labor, and in so doing create more poverty by limiting job opportunities. Occupational licensure laws provide one good example of such poverty-inducing regulations.21The following discussion is adapted from Steven Horwitz, “Breaking Down the Barriers: Three Ways State and Local Governments Can Get Out of the Way and Improve the Lives of the Poor” (Mercatus Research, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, July 2015), http://mercatus.org/publication/breaking-down-barriers-three-ways-state-and-local-governments-can-improve-lives-poor. Occupational licensure laws are found at the state and municipal level and set the conditions required to obtain licenses to perform a variety of different jobs. Getting a license frequently involves costly and time-consuming preparation for exams. These costs serve as barriers to entry that limit competition in the industry being licensed, resulting in higher profits for incumbents and lost job opportunities for potential competitors. Occupational licensure laws provide another excellent example of the bootleggers-and-Baptists phenomenon mentioned earlier, given the coincidence of the economic interests of the incumbents and the moral concern of those who believe such regulation is needed to protect the safety of consumers. The “public safety” argument for licensure is less than persuasive when licenses are required for jobs such as interior design, which pose no safety threat to the public.

Licensing clearly increases the wages of incumbents, or those fortunate enough to obtain a license in the face of these barriers.22Morris Kleiner and Alan Krueger estimate that licensing increases wages by about 15 percent, and that when licensing is combined with union membership, the wage premium averages 24 percent. See Morris M. Kleiner and Alan B. Krueger, “The Prevalence and Effects of Occupational Licensing,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48 (December 2010): 685.However, these gains have to be set against the costs borne by those trying to get a license and the costs of less employment or pay for those who choose lower-paying alternatives after being discouraged by the costs of the licensing process. Even those who get licenses and higher pay may see some or all of their gains absorbed by dues or fees to the licensing boards required to maintain their protected status. But most important for our argument is the fact that incumbents and those most likely to obtain licenses are likely to have higher incomes than those they are attempting to exclude. If the potential workers excluded by licensing are poorer than those who benefit from it, occupational licensing is regressive and helps to perpetuate existing poverty.

The Institute for Justice looked at 102 low- and moderate-income occupations that require licenses. The researchers found that all 50 US states and the District of Columbia require licenses for at least some of these occupations. The number of occupations licensed in each jurisdiction ranges from 24 to 71 of the 102 studied.23Dick M. Carpenter II et al., License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, 1st ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, May 2012), https://ij.org/report/license-to-work/.The licensed worker categories included florists, interior designers, auctioneers, manicurists, and preschool teachers. Some occupations are licensed in certain states but not in others.24The fact that some states require licenses for certain occupations but other states do not require licenses for the same occupations suggests that the goal of licensing is not to protect public safety, but instead to serve as an opportunity for “bootleggers” to benefit by foreclosing competition. After all, if an occupation is safe in one state, why would it be unsafe in another? The licensed incumbents also tend to control the licensing boards, and there is evidence they can adjust fee amounts and the difficulty of tests to raise or lower the barrier to lower-income applicants. On average, the licensing process required “$209 in fees, one exam and about nine months of education and training,” but that average is highly variable across states.25Carpenter et al., License to Work. For those with lower incomes, particularly new entrants to the labor market, these requirements are burdensome.26Chapter Two, pages 19–44 in this volume, by Alicia Plemmons and Edward Timmons, provides additional depth to many of the issues about occupational licensing raised in the last few paragraphs.

Part of the burden concerns the fact that about half of the licensed occupations pertain to businesses that can be run easily and cheaply from one’s home or a low-rent storefront. Licensing blocks the path to business creation, ownership, and expansion, which is often a path out of poverty. Finally, those who practice in these licensed lower-income occupations are more likely to be nonwhite and less-educated than the general population, and they have an annual average income 37 percent lower than the average for the US population as a whole.27Carpenter et al., License to Work. Occupational licensing has a clear tendency to harm the relatively poor more than the relatively well-off, and thereby make it more difficult to escape poverty.

Another effect of both minimum-wage laws and occupational licensure is that they increase the prices of various goods and services. In general, lower-income households are less able to absorb such price increases than higher-income households, because the added costs are larger as a percentage of their household budgets. The result is that poor households find their budgets stretched, making it more difficult for them to save or to become licensed themselves, which further traps them in poverty. For example, consider cities in which regulators have banned ride-sharing services such as Uber or Lyft. Besides restricting employment opportunities for the poor, this policy raises the price of transportation services by reducing competition from lower-priced providers.28This is the consensus view among economists, as found in Jeremy Horpedahl, “Ideology Über Alles? Economics Bloggers on Uber, Lyft, and Other Transportation Network Companies,” Econ Journal Watch 12, no. 3 (2015). By decreasing the amount of transportation that consumers can afford and requiring them to pay more for what they use, this policy contributes to the perpetuation of poverty in the midst of plenty in the US.

Occupational licensing laws frequently affect professions that can easily be the source of small business start-ups. For example, incredibly strict cosmetology licensing laws make it very difficult for people, especially women of modest means, to go into business for themselves providing those services. Licensing day-care providers both increases the costs of day care, which particularly burdens lower-income households, and makes it harder for prospective providers, who are themselves often relatively poor, to start a day-care business.29Ryan Bourne, “The Regressive Effects of Child-Care Regulations,” Regulation 41, no. 3 (2018): 8–11.[.mfn]

In addition to licensing laws, a variety of business regulations raise the cost of starting small businesses, which makes upward mobility more difficult in the US and other advanced economies. These regulations include zoning and other restrictions on home-based businesses, as well as limits on mobile businesses such as food carts and street vendors. Although the effects in advanced economies are real, they pale in comparison to the problems created by similar but more draconian laws in poorer countries.

Despite what might be the good intentions behind them, zoning laws, like occupational licensure laws, suffer from a bootleggers-and-Baptists problem, because they are often a tool used by the politically influential to block market access by lower-cost competition. In Chicago, for example, starting a new business requires a $250 license that must be renewed every two years, and violating this law will cost at least that amount per day. Renovating a home to accommodate a business requires completing a variety of forms, as well as an application process controlled by the Department of Planning and Development.29Elizabeth Milnikel and Emily Satterthwaite, Regulatory Field: Home of Chicago Laws, special updated ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, November 2010), http://ij.org/images/pdf_folder/city_studies/ij-chicago_citystudy.pdf. Even something as small as changing a sign can require dozens of hours and forms. Chicago regulations limit home-based businesses to no more than one employee who does not live in the home, and such businesses cannot manufacture or assemble products unless they sell them directly to retail customers who come to the home.30Milnikel and Satterthwaite, Regulatory Field. It is not clear what the Baptist argument is here, but the bootleggers are obvious.

Street vending and operating food trucks offer an excellent way for lower-income people to start the climb out of poverty, because they require relatively little start-up capital and make use of preexisting skills. Unfortunately, municipal regulations frequently make working in this way harder than necessary. Chicago requires a “peddler’s license” and puts severe limitations on the places street vendors can operate. Food trucks cannot prepare food “on the street” without a specific, additional license and are subject to a large number of restrictions, including a requirement that they operate at least 200 feet away from a physical restaurant.31Milnikel and Satterthwaite, Regulatory Field. That regulation is a classic bootleggers-and-Baptists story: the owners of the brick-and-mortar restaurants play the role of bootleggers by lobbying for the restriction (among other restrictions), while Chicago aldermen play the Baptists by claiming that such rules are necessary to promote “entrepreneurship” in the restaurant industry. Unlike other provisions of Chicago regulations, which might plausibly be related to food safety or traffic issues, this rule is clearly designed to protect industry incumbents from the real entrepreneurial threat of food trucks.32Elan Shpigel, “Chicago’s Over-Burdensome Regulation of Mobile Food Vending,” Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy 10 (2015): 354–88.

Many Chicago food trucks end up operating “in the shadow of the law,” and more than a third of them have reported harassment from law enforcement while almost half have complained that legal uncertainty is one of the biggest impediments to their business.33Michael Lucci and Hilary Gowins, Chicago’s Food-Cart Ban Costs Revenue, Jobs (Special Report, Illinois Policy Institute, Chicago, IL, August 2015), https://www.illinoispolicy.org/reports/chicagos-food-cart-ban-costs-revenue-jobs/. The vast majority of food truck operators in Chicago are nonwhite and many of them report that that they got started with a food truck because of poor employment options in the city, or because of their age or health.34Lucci and Gowins, Chicago’s Food-Cart Ban. Food trucks offer a way out of poverty, and regulations and police harassment that raise the costs of entering or continuing in that business perpetuate poverty.

Street vendors in Philadelphia and other cities face similar restrictions.35Robert McNamara, “No Brotherly Love for Entrepreneurs,” Institute for Justice, Arlington, VA, November 2010, http:// ij.org/images/pdf_folder/city_studies/ij-philly_citystudy.pdf. New York City has a citywide limit on the number of food vending permits it issues, and it can take months and multiple forms to get a permit. Some of these forms are only available in English, raising the costs of getting started as a vendor for low-income immigrants.36Entrepreneurs seeking to open a food cart also need a separate permit for their cart, and the number of those permits is capped. The result of these regulations is a black market for the various permits, with prices ranging from $10,000 to $20,000 for a permit lasting two years. Such costs will be prohibitive for many low-income households, which in turn will extend their time in poverty.37Miriam Berger, “Your Favorite Food Vendor Could Get Arrested,” Salon, November 24, 2013, http://www.salon.com/2013/11/24/your_favorite_food_vendor_could_get_arrested/.

Finally, the general business permit approval process can be highly burdensome, and it varies significantly across cities. A recent US Chamber of Commerce study found that Chicago not only averaged 32 days to approve a permit for a professional services business, it charged $900 for doing so.38US Chamber of Commerce Foundation, “Enterprising Cities: Regulatory Climate Index 2014—Section 1,” accessed August 27, 2020, http://www.uschamberfoundation.org/regulatory-climate-index-2014-section-i. The state of Illinois then charged an additional $500, plus an annual fee of $250, to let a business organize as a limited liability company. The Chicago examples are above the national average, but almost every major city imposes some sort of significant permit-related burden on new businesses. Because all the regulations discussed in this section have regressive effects, it is not surprising that economists Dustin Chambers, Patrick McLaughlin, and Laura Stanley found that, at the state level, a 10 percent increase in the “effective federal regulatory burden . . . is associated with an approximate 2.5% increase in the poverty rate.”39Dustin Chambers, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Laura Stanley, “Regulation and Poverty: An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between the Incidence of Federal Regulation and the Occurrence of Poverty across the US States,” Public Choice 180 (2018): 134.

If we are serious about addressing poverty in the US, one way to start is to remove all the barriers discussed in this section and allow people of modest means to seek out the jobs they want at wages they are satisfied with, allow them to enter various occupations without the regulatory barriers associated with licensing, and make it easier for them to start small businesses, whether out of their home, a food truck, or a street vendor’s cart. For example, certification provides an effective and much-lower-cost alternative to licensing. The municipal regulatory process has too often been captured by wealthy, politically influential incumbents who see lower-income households wanting to work or start new businesses as competition to be eliminated rather than as people whose aspirations for upward mobility should be encouraged. Reducing the burdens placed on those who want to work would help address the poverty amid plenty that characterizes parts of the US and other places in the Western world.

Regulation and Poverty in Senegal

Drawing on one of the authors’ experience as an entrepreneur in both the US and Senegal, we can explore the effects of regulation in Africa with a case study of the challenges facing entrepreneurs in Senegal. Senegal is a former French colony that gained independence from France in 1960. The newly independent nation largely inherited French colonial law. Senegal’s first two presidents, who governed the country from 1960 to 2000, were socialists. Thus the Senegalese legal system is inherited from a state-centric civil law nation in Europe, modified by 40 years of socialism and its associated cronyism and rent-seeking. It is very far from an optimal legal system for business and generating economic growth.

In fact, most African nations place near the bottom of the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rankings as well as the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World rankings.40World Bank, Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform, 2019, https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Annual-Reports/English/DB2019-report_print-version.pdf and James Gwartney et al., Economic Freedom of the World: 2019 Annual Report (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, 2019). Senegal ranks 124th out of 162 countries on the Economic Freedom of the World Index (on the basis of 2017 data), placing it in the least economically free quartile. On regulation, Senegal ranks 147th out of 162, putting it among the most regulated economies in the world, with only about 10 percent of countries scoring worse. It ranks 114th on the measure for Legal System and Property Rights, which puts it in the lower end of the third quartile.41See the data on Senegal at the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom database, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/economic-freedom/map?geozone=world&page=map&year=2017&countries=SEN#country-info (accessed August 27, 2020), which uses data from James Gwartney et al., Economic Freedom of the World: 2019 Annual Report (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, 2019). Senegal is also among the world’s poorer countries. In regard to GDP per capita, Senegal ranks 149th out of 185 countries on the basis of 2018 data from the World Bank.42https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?most_recent_value_desc=true Given Senegal’s lack of economic freedom, particularly its high regulatory burden, weak property rights, and ineffective legal system, as well as an ethical legacy from colonialism and socialism that is not friendly to markets and trade, Senegal’s poverty is not a surprise.

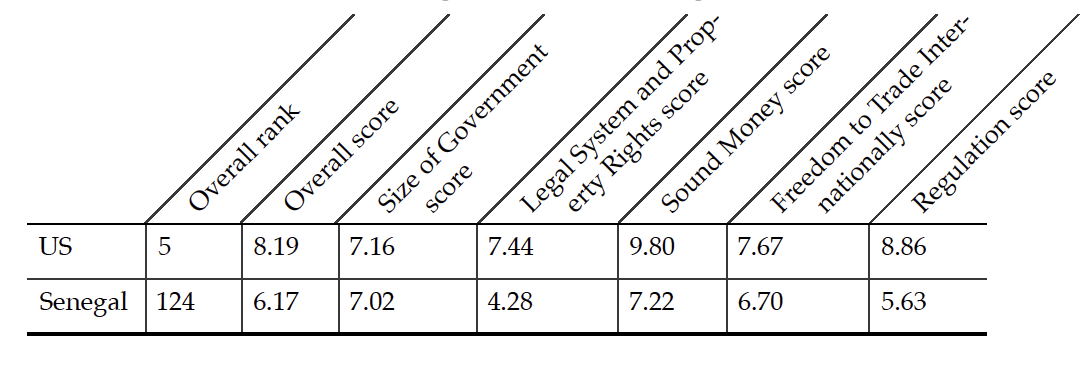

Table 2 compares the US and Senegal on the Economic Freedom of the World rankings by specific category. Although the two countries are not that far apart in terms of the size of government, where they diverge is on the issues central to our argument: legal systems and property rights, as well as regulation. The combination of a high regulatory burden and a lack of rule of law and lack of protection for property and contracts is particularly problematic for economic growth in general and poverty relief specifically.

Table 2. Economic Freedom of the World Rankings—US and Senegal, 2017

Note: Rank is out of 162 countries. All scores are out of 10.

Source: Data on US and Senegal at the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom database, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/economic-freedom/map?geozone=world&page=map&year=2017&countries=SEN#country-info (accessed August 27, 2020), which uses data from James Gwartney et al., Economic Freedom of the World: 2019 Annual Report (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, 2019).

A closer look at the regulatory burden on entrepreneurs helps to explain the link between Senegal’s economic freedom ranks and its poor economic performance In the US, entrepreneurs can set up a limited liability company in minutes online, and also quickly open a bank account. Prospective entrepreneurs have hundreds of choices in banking with diverse service packages all competing for their business. In the US, entrepreneurs can easily have ingredients, packaging, manufacturing equipment, shipping materials, and so forth shipped to them quickly, in many cases overnight. Orders can be made online and paid for with a credit card, and firms have thousands of choices of vendors all competing to serve them. US entrepreneurs can more or less hire and fire as they please, and—while taxes normally require an accountant—compliance with tax law is not overly burdensome for a small business.

In Senegal, by contrast, it can take a year to open a new business if one follows the official, formal procedures. Opening a business requires entrepreneurs to work with several bureaucratic offices. As part of the process, a notary public must be paid a fee of $200, which is about a one-fifth of a year’s income for the average Senegalese.43World Bank, Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform; Economy Profile of Senegal, n.d., http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/529461541164094928/pdf/131734-WP-DB2019-PUBLIC-Senegal.pdf. Often bureaucrats do not show up to meetings, or show up late. Once they arrive, they often are not sure whether they are using the right procedure. They might lose paperwork, or they might stall in an attempt to get a small bribe to move forward. All these impediments are significant regulatory barriers and transaction costs that prevent entrepreneurs with good ideas from putting those ideas into practice in ways that could benefit the Senegalese public.

If they can get their business approved, entrepreneurs have very limited banking options because banking in Senegal is a state-managed oligopoly. The few players provide customers with few options and high fees. There are substantial minimum deposits needed to open a business account—again, often in excess of a year’s salary for the average Senegalese person.44World Bank, Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform, 2019. Once the funds are in the bank, transfers are expensive and time consuming. In contrast to the US, in Senegal bank personnel are more like government bureaucrats than service providers competing for customers.

After the long process of getting the needed approvals and bank accounts, when entrepreneurs want to begin operations, they find that almost nothing is available in Senegal. Take a simple cardboard box. In the US, one finds an endless array of cardboard box options and multiple firms that provide them. In Senegal, there are exactly two vendors and they offer only custom sizes, with a minimum quantity of 1,000 boxes per size, which is often much more than is needed. (As of January 2021, the larger vendor forced the smaller vendor out of business. There is now just one.) The result is wasted capital investment in supplies that will not be needed for far into the future. Because the costs of opening a new small business are so high, even a for-profit entity supplying something like boxes in a competitive market is typically accustomed to working with a relatively small number of large corporate customers rather than with small entrepreneurs.

These obstacles to creating legal businesses have created a massive “missing middle” problem in Senegal and across Africa. The “missing middle” refers to the fact that there are plenty of “microentrepreneurs” (i.e., poor people struggling to buy and sell out of necessity but with little or no real business structure because they remain in the black or gray market), and there are larger multinational corporations that have the resources to jump through the hoops of African bureaucracies. What is missing are entrepreneurial small businesses that have the protection of the law because they operate in a legal market.

The microentrepreneurs either cannot afford to create a legal business or prefer not to because they do not want the tax and regulatory hassles associated with doing so. As a consequence, they largely remain invisible, as black-market businesses must be. They have no legal rights to anything, they cannot obtain a bank account, they have no insurance, and they cannot guarantee their products through public certifications of quality—thus they do not typically develop into substantial businesses. This is one reason why cardboard boxes are not readily available in Senegal: there is not an adequate small business market to support them.45This demonstrates both the interconnections among various businesses and the insight dating back to Adam Smith that the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market. There is a chicken-and-egg problem here in that there would be more small entrepreneurs if there were more other small entrepreneurs selling supplies for that market. Because there are so few entrepreneurs, there is no ecosystem of professional small business service providers to support fast, efficient business operations.

The Dutch Good Growth Fund, an impact fund seeking to address the missing middle issue in West Africa, commissioned several studies in 2018. The researchers confirmed that most informal entrepreneurs perceive the process of going formal as too costly (in time and money) and too complex to make it worthwhile. In part, this is because one of the ways in which small business can get access to the formal credit system does not exist in West Africa. In the words of one researcher, “There are barely any players that can offer external funding (that is not collateralized debt) in the range of 10,000–1 million Euros.”46Ekta Jhaveri, “Closing the Gap: Identifying Key Challenges for the Missing Middle SMEs in Francophone West Africa,” Next Billion, February 20, 2018, https://nextbillion.net/closing-the-gap-identifying-key-challenges-for-the-missing-middle-smes-in-francophone-west-africa/. Without the ability to get loans of that size, it does not pay to try to make use of the formal credit system.

At the other end, the multinational corporations have dedicated teams of lawyers and accountants to help them navigate the formal credit processes. This parallels the US situation, because multinational firms in Africa face substantial compliance costs. There is no reason to think that a displacement of lower-wage jobs does not take place in Africa as in the US, with the same regressive consequences. The multinational firms also have enough influence that politicians will grant them special exemptions unavailable to small entrepreneurs in order to attract their business. Because the multinational companies can rely on their own internal support services, they never have to deal with the absence of firms and institutions that Western businesses take for granted. Small businesses, by contrast, must find a way to deal with the fact that there are no networks of FedEx locations, no Office Depots, and no overnight delivery of millions of products.

In Senegal, all these things are personal rather than routinized through formal institutions. When economic activity is based on who one knows, the transaction costs of getting things done rise substantially. The ability of multinational firms to avoid those costs by doing things internally gives them a huge advantage over small businesses. The way in which regulations prevent new small businesses from opening, combined with the lack of a structure to support small businesses, contributes to the impoverishment of the Senegalese through both higher prices and fewer opportunities to earn an income.

Labor market regulations also impose large costs on entrepreneurs. When one hires an employee in Senegal, one is essentially married to the employee for life. By law, the government requires that entrepreneurs obtain approval before they lay off an employee. This situation encourages businesses not to hire people in the first place and to become more capital-intensive, reducing employment opportunities for those who need jobs the most. These employment rules make it hard for small businesses to adjust to inevitable fluctuations in demand by varying their labor force.47In 2010, Senegal was ranked 172nd out of 183 nations in the Ease of Doing Business index, which indicates that it is one of the most difficult nations in the world in which to employ workers. Subsequent Doing Business reports quit reporting rankings on employing workers because of labor organization pressure. World Bank, “Ease of Doing Business Rankings,” Doing Business 2019, accessed September 17, 2020, https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings. In practice, most Senegalese companies hire people as independent contractors to avoid the costs associated with these rules. However, doing so means that entrepreneurs cannot provide a real benefits package to their employees. Not only do these labor regulations mean fewer jobs, they also mean fewer benefits for those who do get work.

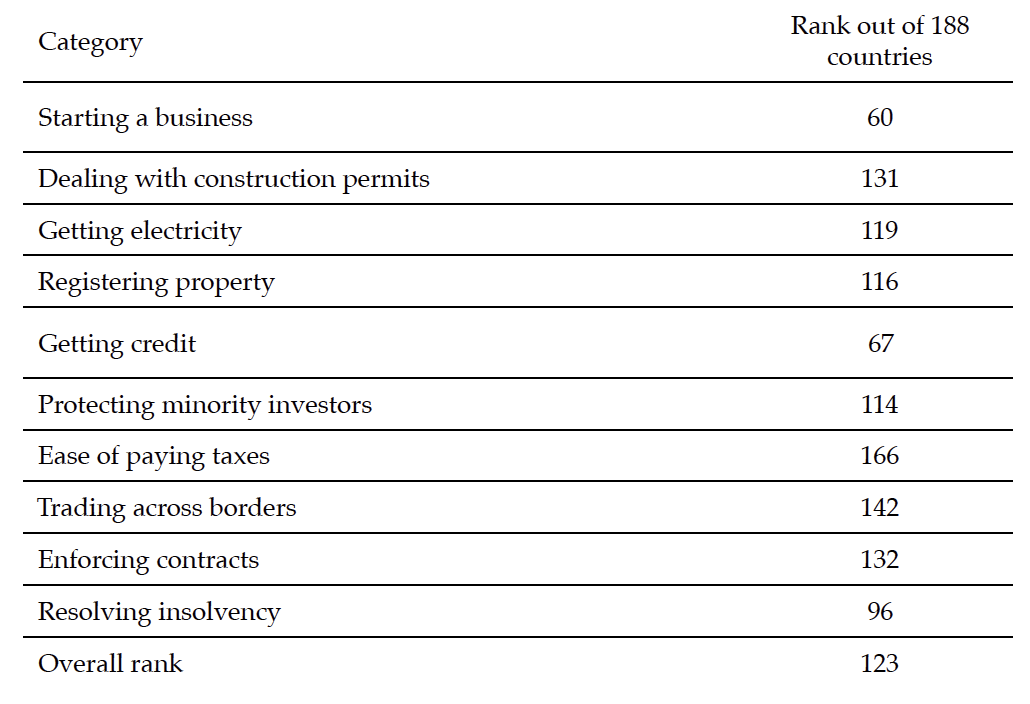

Paying business taxes in Senegal is an impossible, Kafkaesque task. The complexities of Senegalese value-added tax law are such that even government officials do not understand how rules of the tax apply, which might explain why Senegal is ranked near last on the Ease of Doing Business index on taxation. The ambiguity of the law opens up the possibility of selective enforcement and the use of regulation as a political weapon, further raising the costs of starting and maintaining small businesses. Similar ambiguities and selective enforcement affect everything from property rights to building permits, creating an environment of uncertainty that discourages entrepreneurship and the wealth and jobs it brings. The environment of uncertainty also encourages those with resources and access to political power to seek out regulations that benefit them or harm their (potential) competition, diverting resources from the positive-sum game of trade to the negative-sum game of transfers. Table 3 summarizes Senegal’s ranks on all the elements of the World Bank’s overall Ease of Doing Business index.

Those businesses that do manage to get started in Senegal and deal with all these problems will also face tariffs as high as 35 percent on a large variety of imports, as well as a value-added tax of an additional 18 percent, making the full tax burden potentially over 50 percent.48See the data from the World Bank at “Senegal Imports, Tariff by Country and Region 2018,” World Integrated Trade Solution database, accessed August 27, 2020, https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/SEN/Year/LTST/TradeFlow/Import/Partner/all/. Some entrepreneurs may be able to get specific exemptions by spending enough time jumping through the right bureaucratic hoops, but doing so is only worthwhile for a small number of businesses selling relatively high-end consumer goods for the US market. Most small businesses either smuggle goods into the country or use inferior local substitutes—or they never come into existence at all.

Note the devastating impact of the regulations, tariffs, taxes, uncertain property rights, and permit systems described in this section: collectively they have almost completely killed off the ecosystem of legal, entrepreneurial small and medium-sized businesses that are essential to employment and broad-based growth and prosperity. This is why almost all business in Senegal is either informal or captured by large corporations, and why Senegal suffers from the missing middle. It is also why youth unemployment is such that “more than 70% of the youth in the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Mali, Rwanda, Senegal and Uganda are either self-employed or contributing to family work.”49John Page, “For Africa’s Youth, Jobs Are Job One,” in Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent in 2013 (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2013), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Foresight_Page_2013.pdf. It is also why so many young Senegalese leave for Europe in small fishing boats, accepting a very real risk of dying at sea. The costs of regulation are not just about material well-being.

Table 3. Rank for Senegal in World Bank Ease of Doing Business Index, 2019

Note: Rank is out of 188 countries.

Source: World Bank, “Ease of Doing Business Rankings,” Doing Business 2019, accessed September 17, 2020, https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings.

An Agenda for Reform

As policymakers and researchers think through how to reform the regulatory state to reduce its regressive effects, there are important differences between the challenges facing the US and those facing Senegal and other places where the Great Enrichment has yet to spread. But one common reform that could help in both places is requiring that all new regulatory proposals include an analysis of their effects on lower-wage workers and the poor more generally. The stated rationale for many regulations is such that those who analyze their effects have little reason to ask questions about their effects across income levels. Analyses should cover the effects on employment and new business creation as well as prices of outputs, because all of those can affect poverty. Requiring that analysts ask the question about distributional effects is no guarantee that analyses will be performed well or that their results will influence political decision makers, but it would at least recognize that regulations can often prevent upward mobility (in the US) or the development of a middle class in general (in Senegal and elsewhere).

A second general proposal for reform starts by recognizing that many regulations are intended to protect larger incumbent firms against competition from smaller firms, or those considering entering the industry. Our discussion of the bootleggers-and-Baptists phenomenon indicates that we need to watch for the “bootleggers” who are proposing regulations that use the arguments of the “Baptists” as cover for their own financial self-interest. Requiring statements of financial interest by those proposing or supporting new regulations (much as is expected of researchers who take positions on policy issues) would be helpful, as would soliciting the views of smaller competitors in the regulated industry or of small entrepreneurs in other industries who have faced similar regulatory barriers. These are difficult problems to overcome because of the concentrated benefits and dispersed costs of regulation, but calling attention to them would be a start.

A third general reform that all could benefit from, particularly those in the poorer parts of the world, is to ensure that the regulation that does exist remains clear and predictable and is enforced consistently. As we saw in the case of Senegal, a lack of clarity and weak enforcement of the rule of law exacerbate the ways in which regulation contributes to poverty. Barriers to the creation and continued operation of businesses are problematic enough on their own, but they are worse when entrepreneurs are unsure about the nature of the rules and their enforcement.

In Senegal, the necessary changes will be more difficult given the more deeply entrenched institutional problems. One strategy for reform should be to find ways to enable the existing informal economy to become part of the formal economy. There is clearly no lack of entrepreneurial spirit in Senegal’s informal economy. Rather, those entrepreneurs are prevented from having the maximum positive effect on economic growth and upward mobility by the regulatory barriers that raise the costs of entering the formal economy, and thereby favor the larger multinational companies that can pay those costs.50The work of Hernando de Soto is instructive along these lines about the relationship between in the informal and formal sectors in poorer countries. See, for example, Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (New York: Basic Books, 2000). The foundation for a reduction in poverty is there, both through more employment opportunities and greater output leading to lower prices, but it is being suffocated by the regulatory state and the lack of clear, consistent, and equitably enforced rules.

The problems in the US are much more specific, because particular regulations, rather than the deep institutional structure, are the relatively larger problem. Poverty reduction through regulatory reform will require a close look at regulations such as occupational licensure, zoning, business licenses, and others that raise the cost of starting a business, or staying in business, without a clear, corresponding social benefit. The benefits to incumbents of raising rivals’ costs are private gains reflecting a negative-sum and regressive transfer. Absent a clear social benefit to such regulations, they need to be repealed so that the least well-off can reap the full benefits of competition. The evidence is clear that a vigorous and competitive market economy, framed by well-defined and enforced property rights, the rule of law, and sound money, has enabled much of humanity to emerge from poverty. The reforms listed above would enhance that vigor and competitiveness in any place that adopts them.

Conclusion

A close look at the effects of economic regulation in the US and Senegal indicates the ways in which it perpetuates poverty among both least well-off in the West and the global poor. If we want to encourage upward mobility in the West and significantly reduce poverty in places like Senegal, we need to free the skills and energy of entrepreneurs from the burden of excessive regulation. For places like the United States, this means taking seriously the regressive effects of a whole variety of regulations that inevitably serve the interests of incumbent firms with access to political power rather than actually protecting consumers, workers, or entrepreneurs. Much of the regulatory structure is, in practice, a redistribution from the poor and powerless to the wealthier and more powerful.

In places like Senegal, the scale of change will have to be greater, and it will require a serious commitment to the more fundamental liberal institutions: the rule of law, contracts, and property rights. It will also require a recognition that markets, exchange, and liberal institutions more broadly have their own African roots and are the path to prosperity, not a harmful legacy of Western colonialism and imperialism. The West grew rich by giving people the freedom and moral approval to author their own life projects, in which entrepreneurial ventures and choices of employment are often central, by ending arbitrary political interference and regressive regulations. That recipe still works today as a way to extend the wealth currently enjoyed by so many in the West to the poor in the West and across the globe.

References

Bailey, James B., Diana W. Thomas, and Joseph R. Anderson. “Regressive Effects of Regulation on Wages.” Public Choice 180 (2019): 91–103.

Berger, Miriam. “Your Favorite Food Vendor Could Get Arrested.” Salon. November 24, 2013. http://www.salon.com/2013/11/24/your_favorite_food_vendor_could_get_arrested/.

Bourne, Ryan. “The Regressive Effects of Child-Care Regulations.” Regulation 41, no. 3 (2018): 8–11.

Carpenter, Dick M. II, et al. License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing. 1st ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, May 2012). https://ij.org/report/license-to-work/.

Chambers, Dustin, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Laura Stanley. “Regulation and Poverty: An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between the Incidence of Federal Regulation and the Occurrence of Poverty across the US States.” Public Choice 180 (2018): 134.

Cox, W. Michael and Richard Alm. Myths of Rich and Poor: Why We’re Better Off Than We Think (New York: Basic Books, 1999).

Gwartney, James, et al. Economic Freedom of the World: 2019 Annual Report (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, 2019).

de Soto, Hernando. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (New York: Basic Books, 2000).

Horpedahl, Jeremy. “Ideology Über Alles? Economics Bloggers on Uber, Lyft, and Other Transportation Network Companies.” Econ Journal Watch 12, no. 3 (2015).

Horwitz, Steven. “Breaking Down the Barriers: Three Ways State and Local Governments Can Get Out of the Way and Improve the Lives of the Poor.” (Mercatus Research, Mercatus Center at George Mason University. July 2015). http://mercatus.org/publication/breaking-down-barriers-three-ways-state-and-local-governments-can-improve-lives-poor.

Horwitz, Steven. “Inequality, Mobility, and Being Poor in America.” Social Philosophy and Policy 31, no. 2 (Spring 2015): 70–91.

Horwitz, Steven. “The Costs of Inflation Revisited.” Review of Austrian Economics 16 (2003): 77–95.

Jhaveri, Ekta. “Closing the Gap: Identifying Key Challenges for the Missing Middle SMEs in Francophone West Africa.” Next Billion. February 20, 2018. https://nextbillion.net/closing-the-gap-identifying-key-challenges-for-the-missing-middle-smes-in-francophone-west-africa/.

Kleiner, Morris M., and Alan B. Krueger. “The Prevalence and Effects of Occupational Licensing.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48 (December 2010): 685.

Leonard, Thomas C. Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 2016).

Lucci, Michael and Hilary Gowins. Chicago’s Food-Cart Ban Costs Revenue, Jobs (Special Report, Illinois Policy Institute. Chicago, IL. August 2015). https://www.illinoispolicy.org/reports/chicagos-food-cart-ban-costs-revenue-jobs/.

McCloskey, Deirdre N. Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

McCloskey, Deirdre N. The Bourgeois Virtues (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

McNamara, Robert. “No Brotherly Love for Entrepreneurs.” Institute for Justice. Arlington, VA. November 2010. http://ij.org/images/pdf_folder/city_studies/ij-philly_citystudy.pdf.

Milnikel, Elizabeth and Emily Satterthwaite. Regulatory Field: Home of Chicago Laws. Special updated ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, November 2010). http://ij.org/images/pdf_folder/city_studies/ij-chicago_citystudy.pdf.

Mokyr, Joel. The Lever of Riches (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

Neumark, David and William Wascher. “Minimum Wages and Employment.” Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics 3, no. 1+2 (2007): 1–182.

North, Douglas C. Structure and Change in Economic History (New York: W.W. Norton, 1981).

Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy 10 (2015): 354–88.

Olson, Mancur. The Rise and Decline of Nations (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1982).

Page, John. “For Africa’s Youth, Jobs Are Job One.” in Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent in 2013 (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2013). https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Foresight_Page_2013.pdf.

“Senegal Imports, Tariff by Country and Region 2018.” World Integrated Trade Solution database. Accessed August 27, 2020. https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/SEN/Year/LTST/TradeFlow/Import/Partner/all/.

Shpigel, Elan. “Chicago’s Over-Burdensome Regulation of Mobile Food Vending.”

Silver, Laura and Courtney Johnson. “Internet Connectivity Seen as Having Positive Impact on Life in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Pew Research Center. October 9, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/10/09/internet-connectivity-seen-as-having-positive-impact-on-life-in-sub-saharan-africa/.

Thierer, Adam. Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom. rev. and exp. ed. (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University. 2016). https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Thierer-Permissionless-revised.pdf.

Thomas, Diana. “Regressive Effects of Regulation.” Public Choice 180 (2019): 1–10.

US Chamber of Commerce Foundation. “Enterprising Cities: Regulatory Climate Index 2014—Section 1.” Accessed August 27, 2020. http://www.uschamberfoundation.org/regulatory-climate-index-2014-section-i.

World Bank. “Decline of Global Extreme Poverty Continues but Has Slowed: World Bank.” Press release. September 19, 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/09/19/decline-of-global-extreme-poverty-continues-but-has-slowed-world-bank.

World Bank. “Ease of Doing Business Rankings.” Doing Business 2019. Accessed September 17, 2020. https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings.

World Bank. Doing Business 2019: Training for Reform; Economy Profile of Senegal. n.d., http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/529461541164094928/pdf/131734-WP-DB2019-PUBLIC-Senegal.pdf.

Yandle, Bruce. “Bootleggers and Baptists—the Education of a Regulatory Economist.” Regulation 7. no. 3 (1983): 12–16.

Table of Contents

- Regulation and Entrepreneurship: Theory, Impacts, and Implications

- Regulation and the Perpetuation of Poverty in the US and Senegal

- Social Trust and Regulation: A Time-Series Analysis of the United States

- Regulation and the Shadow Economy

- An Introduction to the Effect of Regulation on Employment and Wages

- Occupational Licensing: A Barrier to Opportunity and Prosperity

- Gender, Race, and Earnings: The Divergent Effect of Occupational Licensing on the Distribution of Earnings and on Access to the Economy

- How Can Certificate-of-Need Laws Be Reformed to Improve Access to Healthcare?

- Land Use Regulation and Housing Affordability

- Building Energy Codes: A Case Study in Regulation and Cost-Benefit Analysis

- The Tradeoffs between Energy Efficiency, Consumer Preferences, and Economic Growth

- Cooperation or Conflict: Two Approaches to Conservation

- Retail Electric Competition and Natural Monopoly: The Shocking Truth

- Governance for Networks: Regulation by Networks in Electric Power Markets in Texas

- Net Neutrality: Internet Regulation and the Plans to Bring It Back

- Unintended Consequences of Regulating Private School Choice Programs: A Review of the Evidence

- “Blue Laws” and Other Cases of Bootlegger/Baptist Influence in Beer Regulation

- Smoke or Vapor? Regulation of Tobacco and Vaping

- Moving Forward: A Guide for Regulatory Policy