Regulation creates many perverse incentives. This chapter explores the pressures that overregulation puts on individuals to hide their economic activity from tax authorities and other public officials—that is, to engage in the shadow economy. It is well documented in the academic literature that overregulation relates positively to the size of the shadow economy. This chapter explores shadow economies and investigates some of the leading regulatory burdens that cause them to grow. I also discuss several sensible and low-cost regulatory reforms that discourage informal activity by promoting productive, wealth-generating participation in the formal sector.

Institutions, Entrepreneurship, and Shadow Economies

Institutions are the rules that govern individual action, and social interaction. Economists call them “rules of the game,” and there are formal and informal variants.1Douglas North, “Institutions,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5, no. 1 (1991): 97–112. The rules we find listed among states’ and national constitutions, for example, are formal rules. Those that are not codified, but often adhered to, socially, are informal. Social norms such as handshakes, and holding the door for persons behind you are examples of informal institutions. In this chapter, I will focus primarily on formal rules and how they relate to individuals’ decisions to participate in shadow economies.

In his paper “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive,” economist William Baumol suggests that entrepreneurs are guided by institutions into various forms of activity.2William Baumol, “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive and Destructive,” Journal of Political Economy 98 (1990): 893–921. Productive outcomes, he asserts, are encouraged by institutions that reward wealth creation, and unproductive outcomes by institutions that reward zero- or negative-sum activities—for instance, rent-seeking and frivolous lawsuits.3Several studies investigate this hypothesis. See, for example, Russell S. Sobel, “Testing Baumol: Institutional Quality and the Productivity of Entrepreneurship,” Journal of Business Venturing 23, 6 (2008): 641–55; Travis Wiseman and Andrew Young, “Economic Freedom, Entrepreneurship & Income Levels: Some US State-level Empirics,” American Journal of Entrepreneurship 6, no. 1 (2013): 100–119. Additionally, Young and I examine productive and unproductive outcomes in the context of informal, religious institutions. Travis Wiseman and Andrew Young, “Religion: Productive or Unproductive,” Journal of Institutional Economics 10, no. 1 (2014): 21–45. Rent-seeking involves using the political process to transfer wealth, typically from one group to another. Baumol’s insights into the potential for various forms of entrepreneurship are important. He challenges the common perception of entrepreneurship. Most people, I think, reasonably identify entrepreneurs as those who innovate and accumulate wealth from the popularity of their innovations. We often identify brands such as Apple and Microsoft as outcomes of entrepreneurship—indeed, what Baumol identifies as productive entrepreneurship. However, Baumol alerts his audience to the ubiquity of entrepreneurs—to the fact that the innovative minds around us aren’t limited to those who present us with the goods and services we value most. There are, for example, entrepreneurial minds hard at work innovating new ways to capture wealth through redistribution and the political process! According to Baumol, there is potential to refocus the efforts of such entrepreneurs on wealth creation, simply by adjusting the rules to make productive activity worthwhile and unproductive activity costly.

I mention Baumol here because, while I think his hypotheses are valid, I want to alert the reader to markets people exploit under unfavorable institutions. One question that arises concerning Baumol’s productive and unproductive entrepreneurship hypothesis is this: How do people presently engaged in productive entrepreneurship respond to rule changes that decrease the relative rewards of productive activities? Individuals operating in the legal sector of the economy who are faced with an unfavorable institutional change may, of course, choose to bear the full cost of that adjustment. For example, if a tax policy targeting their industry reduces their disposable income, they may simply carry on their productive activity, only with lower income. However, there are other possible responses. Individuals may migrate to more favorable institutional conditions—such as other states with fewer regulatory burdens—or they may refocus their efforts on legal but unproductive activity. For instance, an electrician burdened by new, onerous code enforcement might choose to become a lobbyist (not likely, but hear me out). Or individuals may simply choose to give up entrepreneurship entirely. Alternatively, they may move their entrepreneurial efforts underground! (This is perhaps the most likely outcome in the case of the overburdened electrician.) By refocusing their efforts this way, these entrepreneurs join the count of shadow economy participants. It is this possibility that I’ll explore in this chapter.

In the sections that follow, I will define the shadow economy and discuss how shadow economies theoretically come to fruition, and how scholars measure shadow economic activity. (After all, we’re talking about activity purposefully undertaken in a way to avoid detection.) I will provide examples of shadow economies in action and discuss associated costs and consequences of shadow economic activity. I will conclude with some suggestions about what can be done to reduce the size of the shadow economy moving forward.

The Shadow Economy

The phrase shadow economy often summons thoughts of prostitution rings and illicit drug sales, of dark alleyways and dimly lit corridors that serve as venues for shady dealings. But shadow transactions, while they may certainly unfold in the sketchiest of places and involve these risky businesses, include much more. The shadow designation generally implies a realm of economic activity in which participants simply prefer to remain out of sight.4The shadow economy has many synonyms—the underground economy, the second economy, black markets, the informal sector, the extra-legal sector, off- the-books economic activity, under-the-table economic activity, hidden economy, parallel economy, cash economies, etc.

There is some debate over the formal definition of shadow economy.5See Friedrich Schneider, “The Shadow Economy and Work in the Shadow: What Do We (Not) Know?” (IZA Discussion Paper No. 6423, Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn, Germany, 2012). Most empirical methodology used to estimate shadow economies focuses narrowly on market activity that is otherwise legal.6This is the common claim made in the literature, though one that is highly debatable. Consider, for example, the electricity consumption variable often used as a shadow economy indicator in estimating shadow economic activity: electricity consumption statistics will measure electricity used for legal market activity and for illegal market activity, such as manufacturing marijuana. Similarly, unemployment statistics used to estimate shadow economy size tell us very little about what unemployed persons are actually doing in the shadow economy.Here, I contend that shadow economic activity consists of all market activity deliberately undertaken in a way to avoid detection by public officials. That is, I consider a shadow economy to include both activity that is at all times illegal—for example, dealing in illegal narcotics—and activity that would be legal if it were not purposefully hidden—for example, under-the-table moonlighting. An unlicensed hairdresser who styles hair for cash and doesn’t report it on her taxes is one example of a shadow economy participant. A contractor working without permits is another. They are working in the shadows along with prostitutes and drug dealers. While some of the services offered by such “entrepreneurs” are questionable, in the Baumolian sense they are all engaged in productive activity—only off the books.

Shadow economies around the world have garnered quite a bit of attention in recent years. In a study of 162 countries (including developing countries, high-income members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, eastern European countries, and central Asian countries), economists Andreas Buehn and Friedrich Schneider find that, on average, shadow economy size is roughly equivalent to 34 percent of GDP.7Andreas Buehn and Friedrich Schneider, “Shadow Economies around the World: Novel Insights, Accepted Knowledge, and New Estimates,” International Tax and Public Finance 19 (2012): 139–71. Countries such as Zimbabwe, Panama, and Bolivia have relatively large shadow economies – with measured sizes of 61.8, 63.5, and 66.1 percent of GDP, respectively.8Table 3 in Buehn and Schneider, “Shadow Economies around the World.” For economies like these, formal economic activity, in terms of value, is less important than underground activity.

The shadow economy of the United States is certainly smaller than the world average, but underground markets in the US still play an important role. Famed journalist Robert Neuwirth, for example, writes of the nation’s black markets during World War II:

In order to channel the nation’s resources for World War II, the United States instituted stringent price controls. Yet, all across the land, people and producers smuggled products across state lines and price-gouged with impunity. As much as 80 percent of the nation’s meat was sold above the price the government mandated, along with 60 to 90 percent of the country’s lumber and one-third of all clothing. Gas was strictly rationed, but 2.5 million gallons a day disappeared, to be sold on the black market. And this doesn’t count counterfeited ration coupons.9Robert Neuwirth, Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy (New York: Random House, 2011), 117.

Economist Hans Sennholz focuses on more recent events:

During the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. Government, in cooperation with the state governments, destroyed millions of jobs. It forcibly raised the cost of labor through sizeable boosts in Social Security levies, unemployment taxes, Workman’s Compensation expenses, Occupational Safety and Health Act expenses, and many other production costs. The mandated raises inevitably reduced the demand for labor and added millions of workers to the unemployment rolls. The boosts also reduced the take-home pay of the remaining workers as market adjustments shifted the new costs to the workers themselves. Both effects, the rising unemployment and the falling net wages, provided powerful stimuli to off- the-books employment.10Hans F. Sennholz, The Underground Economy, online ed. (Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1984), 10, https://cdn.mises.org/The%20Underground%20Economy_3.pdf.

And Buehn and Schneider’s average estimate of the US shadow economy from 1999 to 2007 is 8.6 percent of GDP.11Table 3 in Buehn and Schneider, “Shadow Economies around the World.” This is small only in a relative (to other countries) sense; it is by no means an economically negligible fraction of total economic activity. When government-mandated prices result in shortages, underground markets step in to fill the void. Shadow economies provide a platform for consumers to acquire the goods and services they desire, but are difficult to acquire in the formal sector. Often, shadow economies come to fruition as a response to new policies – and can sometimes counter the intentions of political actors. Therefore, shadow economic activity can have important policy implications. For example, where a larger portion of the population is engaged in underground activity, there will likely be less income from that activity reported to the government. This can result in smaller tax bases from which governments may collect revenue to fund their liabilities. This, in turn, may result in higher budget deficits or tax rates.12Friedrich Schneider and Dominik Enste, “Shadow Economies: Sizes, Causes, and Consequences,” Journal of Economic Literature 38 (2000): 77–114. Hence, political actors across the world search for ways to reduce shadow economic activity.13Hernando de Soto, The Other Path: Economic Answers to Terrorism (New York: Basic Books, 1989); Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (New York: Basis Books, 2000); Neuwirth, Stealth of Nations.

In general, a growing shadow economy can be described as a response of individuals who feel overburdened by the state. Participants either choose the “exit option” if burdens in the formal sector grow sufficiently large, or, alternatively, they never choose the “entry option” as they approach the productive periods of their lifetimes.14Schneider and Enste, “Shadow Economies.”

But what burdens promote shadow market participation? And how do we measure that participation? Researchers have developed theories along with a number of creative ways to measure shadow economic activity.

Measuring the Shadow Economy

Common among the determinants of shadow economic activity are tax and social welfare burdens; licensing, educational requirements, fees and other regulatory barriers to doing business; and labor market burdens. Measuring the effects of these burdens on shadow economy size is not easy, largely because shadow market participants go out of their way to remain undetected. Thus, measuring shadow economy size requires innovative statistical methods, to say the least. The following paragraphs outline a few common methods.

There are both direct and indirect ways to estimate shadow economic activity. Direct methods rely almost exclusively on surveys—which require participants to discuss with a researcher the work they’re doing in the underground. As with any survey data, results are often questionable. (Would you be entirely honest with someone questioning your whereabouts and means of earning illegal income?)

More often, studies of the shadow economy make use of indirect estimation techniques. The use of available indirect techniques varies by the level of the study (e.g., state-level, regional, national) and by data availability. Two widely used indirect methods are the electricity consumption approach and the MIMIC model approach.

The electricity consumption approach dominates the literature surveying shadow economies of central and eastern European countries in the mid to late 1990s and the first few years after 2000,15See, for example, Maria Lacko, “The Hidden Economies of Visegrad Countries in International Comparison: A Household Electricity Approach,” in Hungary: Towards a Market Economy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Maria Lacko, “Electricity Intensity and the Unrecorded Economy in Post-socialist Countries,” in Underground Economies in Transition (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 1999); Maria Lacko, “Do Power Consumption Data Tell the Story? Electricity Intensity and Hidden Economy in Post-socialist Countries,” in Planning, Shortage, and Transformation: Essays in Honor of Janos Kornai (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000); Maria Lacko, “Hidden Economy: An Unknown Quantity? Comparative Analysis of Hidden Economies in Transition Countries, 1989–1995,” Economies in Transition 8, no. 1 (2000): 117–49; Simon Johnson, Daniel Kaufmann, and Andrei Shleifer, “The Unofficial Economy in Transition,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, no. 2 (1997): 159–239. and relies on differences between electricity consumption and GDP. This method of underground estimation is based on the assumption that production requires electricity in both the formal sector and the informal sector. While GDP reports only formal-sector economic activity, electricity— or, more precisely, growth in the consumption of electricity—will give a researcher a better idea of total (formal and informal) production. Researchers track the differences between growth in GDP and electricity consumption, and contest that where there is large divergence (e.g., electricity use growth rates outpace GDP growth rates), there must be unrecorded, unofficial production occurring.

MIMIC is short for multiple-indicators-multiple-causes, and the MIMIC model makes use of a system of equations that relates both potential causes of shadow economic activity and potential indicators that shadow economic activity is occurring to a measure of shadow economy size. While the shadow economy variable is unobservable, the basic idea of this model is to evaluate how several observable causal variables and several observable indicator variables interact with each other. I will spare the reader further technical detail,16For more detail, see Travis Wiseman, “US Shadow Economies: A State-Level Study,” Constitutional Political Economy 24, no. 4 (2013): 310–35. See also other recent studies of the shadow economy. but note that this is the most popular method used in present-day shadow economy studies.

Some Determinants of Shadow Economic Activity

Institutions that discourage productive entrepreneurship simultaneously encourage participation in underground economies. For example, labor market regulations such as occupational licensing effectively restrict the supply of goods and services in the market.

Since their licenses represent protection from potential competitors, license-holders can raise prices on the goods and services they provide. This works to discourage both consumers and future producers from entering the market—that is, the legal market. Entrepreneurs and consumers excluded from the legal sector will often undertake transaction illegally—which can sometimes be dangerous. Economists Sidney Carroll and Robert Gaston demonstrate that in the 1960s as states began implementing licensing requirements for electricians, two things unfolded: (1) the supply of electricians fell (in the formal sector, at least) and (2) incidents of electrocution increased.17Sidney L. Carroll and Robert J. Gaston, “Occupational Restrictions and the Quality of Service Received: Some Evidence,” Southern Economic Journal 47, no. 4 (1981): 959–76. High barriers to entry in the formal sector for electricians raise prices for their services. For some prospective customers, those prices are prohibitively high—though they still want the job done. As a result, inexperienced do-it-yourselfers take high risks that sometimes result in bad outcomes.

Corporate incentive programs produce similar results. When firms win special privilege through the political process—often in the form of tax breaks, credits, and exemptions, for example—they effectively secure a leg up over their competition in the market. And, consumers and non-favored firms suffer for it. Firms that lack the same political privilege may turn to the shadow economy to gain more customers, or they may be forced to downsize their legal operations or, worse, leave the market entirely. Downsizing in any degree results in unemployed workers, who themselves may turn to shadow economies to survive. Minimum wages drive up the price of low-skilled labor—essentially raising production costs for producers who employ this labor—and force employers to focus their hiring decisions on higher-skilled employees. Minimum-wage rules have the effect of (1) preserving employees who are at least worth (to their employers) the current minimum wage and (2) forcing workers who employers perceive as less valuable employees into the shadow economy. Some of these workers will be forced out of work entirely. It is true that, in a minimum-wage-free world, many of these workers would likely earn very low wages, but pushing them into the shadow economy (or out of work entirely) decreases their opportunity to engage in the official economy, which can hurt them in many other ways—such as missing out on resume development and skill building. Taxes are often used to regulate consumer and producer behavior. High taxes tend to increase underground activity. Taxes increase the cost of producing goods and services, raise prices that consumers pay for final products, and reduce disposable income. This heightens the incentive for buyers and sellers to bargain off the books. Have you ever been offered a discount on your purchase for paying in cash?

Welfare programs also generate perverse incentives that encourage shadow economic activity. Many programs are designed to reduce the dollar amount of benefits as recipients earn more income from formal employment—economists sometimes refer to this as an implicit marginal tax. As a result, many people get trapped inside the welfare program. For example, if a welfare recipient finds formal-sector work and her income from said work rises by $6,000 but her welfare benefits are reduced by $4,000, she gains only $2,000 in disposable income. This amounts to a substantial marginal tax rate of approximately 67 percent. Suppose that, in addition to welfare transfers, this person is also earning an off-the-books income of $3,000 that she would have to give up when she accepts the legal-sector position. This amounts to $7,000 in combined welfare benefits ($4,000) and underground income ($3,000) that she would forgo, while earning $6,000 at her new job.

In this case, the welfare beneficiary experiences negative returns (an implicit tax rate of 116 percent), which makes her worse off financially for choosing to pursue legal employment in the face of the welfare program option. She may choose, rationally, to remain in both the welfare program and the shadow economy. The important point here is that income earned in the shadow economy is not reported and therefore does not affect the benefits received from government programs—in contrast to income earned from legal employment. Therefore, high implicit marginal tax rates make participation in the shadow economy more attractive.

Any policy or regulation that raises the cost of doing business in a legal setting, or discourages searching for formal employment, will invariably lower the cost of doing business in the shadow economy. Underground exchanges make up a not-insignificant portion of total US economic activity. Studies suggest that the value of total US shadow economy transactions, in recent years, rests between $1 trillion and $2 trillion annually.18Wiseman, “US Shadow Economies”; Richard J. Cebula and Edgar L. Feige, “America’s Unreported Economy: Measuring the Size, Growth and Determinants of Income Tax Evasion in the U.S.,” Crime, Law and Social Change 57, no. 3 (2011): 265–58. This is a clear indication that shadow economies have important policy implications. Shadow economic activity amounts to potentially billions of dollars in lost tax revenue.

If you’ve ever paid cash to a neighbor for mowing your lawn or babysitting your children,19Lynda Richardson, “Nannygate for the Poor: The Underground Economy in Day Care for Children,” New York Times, May 2, 1993. chances are that you’ve taken part in an underground exchange. A recent study of US shadow economies documents shadow economy size for each of the states, over more than a decade. As an example, on average, Mississippi’s shadow economy is the largest among the 50 states.20Wiseman, “US Shadow Economies.” Estimates place Mississippi’s shadow economy size at 9.54 percent of the state’s economy, on average. What this means is that for every $10 of income generated in the state’s legal sector, nearly one additional dollar is earned in the shadow economy and not reported. In terms of value, on the basis of a 2016 estimate of the state’s real GDP as $95.3 billion, the state’s shadow economic activity amounted to approximately $9.1 billion in 2016. That translates to approximately $3,044 per person.21Shadow economy value estimates are based on the author’s own Real GDP and real GDP per capita estimates come from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, and shadow economy size (9.54%) comes from Wiseman, “US Shadow Economies.” The value of shadow economic activity is derived as real GDP2016 × 9.54%, or $95.3 billion × 0.0954 = $9.1 billion. Similarly, shadow economy value per capita is measured as real GDP per capita2016 × 9.54% = $31,881 × 0.0954 = $3,044.

Consequences of the Shadow Economy

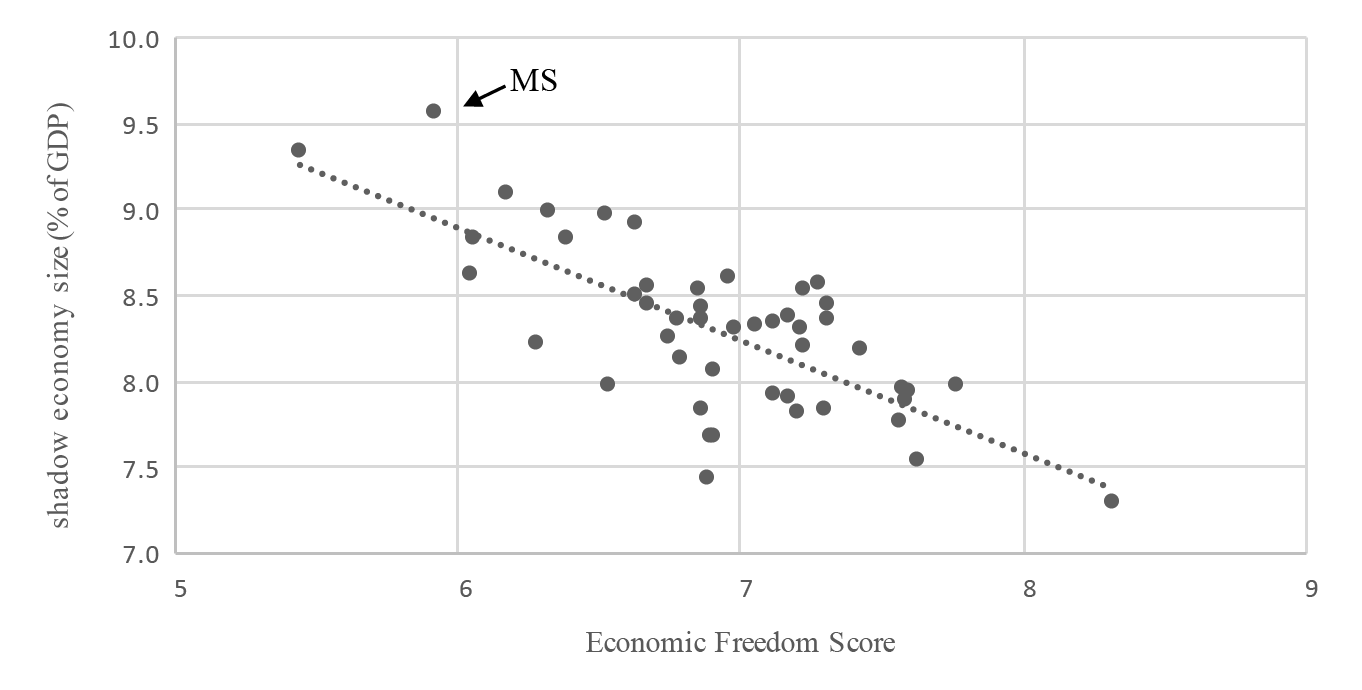

Shadow economies are largest where states rely less on free markets and more on government. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between economic freedom, from the Economic Freedom of North America index,22Dean Stansel, José Torra, and Fred McMahon, Economic Freedom of North America 2016 (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, 2016). and shadow economy size in the US states. Large shadow economies are an indication of just how difficult it is to create wealth in the formal, legal economy. And this difficulty produces a number of downsides. For policymakers, one downside is the lost tax revenue from unreported transactions. However, the downsides to the actual buyers and sellers of underground goods and services may be even worse. Transactions undertaken off the books expose parties of the exchange to risk of being swindled in a number of ways. The purchaser of an underground good or service might end up with a faulty product—we’ve all heard stories of the unlicensed handyman who destroyed more than he fixed or left the job unfinished, then fled the scene. Or the seller of services may be left with a bad check, or with no payment at all. The risks are high because in the underground world there is little legal recourse for bad outcomes.

The situation is more ominous in the market for goods that are at all times illegal—that is, prohibited goods. Prohibitions encourage a lot of bad behavior. Drug markets provide great examples. Since drug suppliers lack legal recourse to, say, prevent the theft of their product, they often take the law into their own hands or purchase protection services from others willing to risk their lives in the underground. History reveals that large underground protection agencies tend to develop around prohibited products for which there remains a very high demand. We know these protection and supply agencies as gangs, mafias, and cartels. When exchanges in these markets go wrong, these problems simply cannot be reported to the legal authorities for restitution. Imagine a drug buyer calling the police to report that the drugs he purchased were tainted, or to report a theft that occurred during the transaction.

Figure 1. Shadow Economy Size and Economic Freedom

Source: Average shadow economy size versus average EFNA score, 1997–2008, constructed by the author, using data from Dean Stansel, José Torra, and Fred McMahon, Economic Freedom of North America 2016 (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, 2016), and shadow economy estimates from Travis Wiseman, “US Shadow Economies: A State-level Study,” Constitutional Political Economy 24, no. 4 (2013): 310-35.

In a recent study published by the Institute for Justice, License to Work, the authors explore 102 low-and middle-income occupations, and document, by state, the number of these that require occupational licensing. It may come as no surprise that states that erect higher barriers to entry in these occupations also tend to exhibit relatively large shadow economies. For example, the states of Mississippi and West Virginia require licenses for approximately 65 percent and 69 percent of these 102 occupations, respectively. These two states also host two of the largest shadow economies, as a percentage of GDP, in the nation (9.54% and 9.32%, respectively). By contrast, two of the smallest shadow economies belong to Colorado and Delaware (7.52% and 7.28%). These states require licenses only for approximately 33 percent and 43 percent, respectively, of the 102 studied occupations.23Dick M. Carpenter II et al., License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, 2017).

“Low- and middle-income” equates to low- and middle-range skill sets—that is, individuals who are limited in their education and training. In other words, licensing in these 102 occupations is aimed disproportionately at those who might benefit most from a job, but simultaneously have the most difficulty overcoming barriers to market entry because they lack competitive skill sets, knowledge, and the income to better develop themselves.

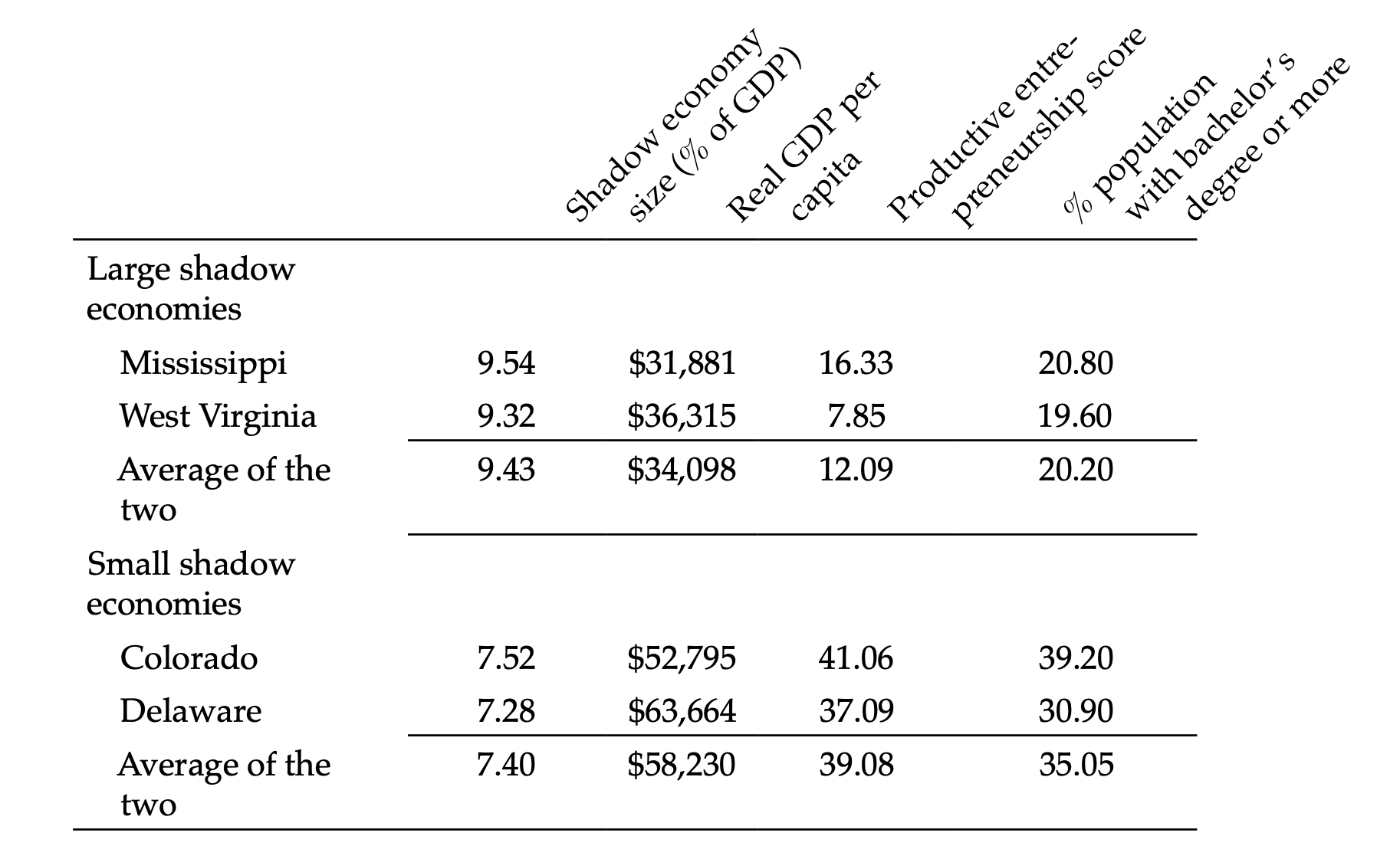

Table 1. Shadow Economy, Income, Entrepreneurship, and Education

Sources: For shadow economy size, Travis Wiseman, “US Shadow Economies: A State-Level Study,” Constitutional Political Economy 24, no. 4 (2013): 310–35. For real GDP, Bureau of Economic Analysis (https://www.bea.gov/data/gdp/gross-domestic-product). For productive entrepreneurship score, Travis Wiseman and Andrew Young, “Religion: Productive or Unproductive,” Journal of Institutional Economics 10, no. 1 (2014): 421-33. For population with bachelor’s degree or more, Census Bureau, Educational Attainment in the United States, 2016.

Though licensing doesn’t explain the full size of shadow economies, barriers like licensing requirements keep the poorest of the population locked in precarious situations—unable to get their footing on the first rung of the economic ladder to prosperity.

Additionally, for comparison, table 1 shows the record of wealth and well-being in Mississippi, West Virginia, Colorado, and Delaware, relative to shadow economy size. Averages of all estimates are provided to demonstrate the remarkable differences in important indicators, such as the states’ real GDP per capita (of legally reported activities), productive entrepreneurship scores,24Productive entrepreneurship scores come from my index of Productive and Unproductive Entrepreneurship Scores and are based on state-level per capita venture capital investments, patents per capita, self-proprietorship (self-employment) growth rates, establishment birth rates, and large establishment (500 employees or more) birth rates. The index offers a 48-point productive entrepreneurship scale, increasing in greater percentages of productive activity. Travis Wiseman and Andrew Young, “Religion: Productive or Unproductive,” Journal of Institutional Economics 10, no. 1 (2014): 421-33. and educational attainment at the bachelor degree level or higher. The states with smaller shadow economies have, on average, a more highly educated population (35.05% with bachelor’s degrees versus 20.20%), experience more formal-sector productive entrepreneurship (an average score of 39.08 versus 12.09), and realize a higher real per capita GDP ($58,230 versus $34,098).

Reducing the size of the underground economy in any of these states would vastly improve the human condition—but would be especially beneficial in the states that consistently demonstrate the largest shadow economies. But how should a state approach its shadow economy? Research suggests that decreases in tax and social welfare burdens, as well as in labor market regulations, are associated with large decreases in shadow economic activity.25Schneider and Enste, “Shadow Economies.” For example, a recent study of US underground economies suggests that a 1 percentage point decrease in burdens from taxes and charges (e.g., licensing fees) is associated with an approximately 0.30 percentage point decrease in shadow economy size, on average.26For measures of both taxes and charges as a percentage of GDP, see Wiseman, “US Shadow Economies.” This may not sound like much, but consider the value of 0.30 percent of Mississippi’s 2016 real state-level GDP. With GDP at a little over $95 billion, a 0.30 percentage point reduction in shadow market activity amounts to approximately $286 million annually. Much of this might be captured in the formal sector once barriers to market entry have been lowered. Most shadow market participants would prefer to do business on the up and up, and they will as long as operating in the legal economy is not prohibitively costly.

Alternatively, the same study suggests that direct attempts to identify and regulate the shadow economy—for instance, increasing police forces to combat underground activity—are associated with much smaller decreases in shadow economic activity. Increasing state expenditures (as a percentage of GDP) for shadow market task forces by 1 percentage point amounts to about a 0.05 percentage point reduction in shadow economy size, on average. Compare this to the aforementioned effect of reducing burdens from taxes and charges (0.30 > 0.05). Moreover, task force measures put additional pressure on taxpayers to fund such initiatives. It is plausible that the increased tax burdens might simply crowd out the efforts of task forces—that is, as task forces reduce shadow economic activity, the taxes required to fund those forces might incentivize more participation in the underground—creating a vicious cycle. Furthermore, entrepreneurs and firms already operating in the shadow economy have an increased incentive under pressure from task force initiatives to innovate new methods to avoid detection.27Recent examples of such innovations include the dark web—a peer-to-peer web platform that houses many services designed to maintain user anonymity in exchanges. Silk Road is one dark web exchange forum where anonymous buyers and sellers exchange illicit goods and services, typically using a cryptocurrency (such as Bitcoin) as a store of monetary value. Pushing shadow market participants deeper underground only increases the costs of maintaining an effective task force.

In fact, prohibitions are possibly the most troublesome regulations imposed in any one place, because they push market activity very deep into the shadows. In addition to incentivizing off-the-books transactions, prohibitions often have consequences that are much more dire—indeed, deadly! Prohibitions—for instance, bans of alcohol or drugs—are often based on the common misperception that if the good or service is prohibited outright, social ills and anxieties associated with consumption of the good or service will simply go away. However, history tells a different story.

In his autobiography, published one year before his death, famed Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel declared, “I never drank so much in my life as the time I spent five months in the United States during Prohibition.”28Luis Buñuel, My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buñuel (New York: Random House, 1982), 45. Buñuel’s assertion illustrates a grand miscalculation among regulators—Prohibition did not destroy demand.

Ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, on January 16, 1919, ushered in a nationwide alcohol prohibition. Alcohol consumption did decline at the onset of Prohibition—due mostly to an immediate and sharp increase in supply costs and search costs (which include the cost and added risk of evading detection by Prohibition agents, etc.), but within a few short years, consumption bounced back to 60–70 percent of its pre-Prohibition levels.29Jeffrey Miron and Jeffrey Zweibel, “Alcohol Consumption during Prohibition,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 81, no. 2 (1991): 242–47.

Underground consumption demands underground supply—and in a world where suppliers lack legal recourse to remedy infringements on their property (such as theft of their booze), they turn to underground protection. Gangsterism is most closely associated with William Baumol’s “destructive” entrepreneur. Gangsters generate wealth in their underground enterprises, but they also loot and murder their competitors.30Ken Burns and Lynn Novick recently directed a three-part documentary series that outlines many of the unintended consequences of Prohibition—including mafia wars and increased fatalities owing to poisoning from poor-quality underground alcohol. Prohibition, directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, written by Geoffrey C. Ward (Prohibition Film Project, 2011). Economist Mark Thornton documents a 67 percent increase in homicides during Prohibition (from 6 persons per 100,000 pre-Prohibition to nearly 10 persons per 100,000 by 1933).31Mark Thornton, “Alcohol Prohibition Was a Failure” (Policy Analysis No. 157, Cato Institute, 1991). The number of homicides dropped substantially following Prohibition’s 1933 repeal.

States Should Provide Shadow Market Participants with an Incentive to Join the Official Economy

The following list is a summary of suggested reforms:

- Reduce Reducing taxes – be it sales, corporate, or personal income taxes — will lower the cost of engaging in the formal economy. Simplifying the tax code is another step states could take to constrain wealth redistribution. Doing this would have the added benefit of reducing the power of lobby groups to profit from the demands they place on bureaucrats, since bureaucrats would be equipped with less to supply. Delaware is one of the nation’s most inviting tax environments for business—the state offers low, fixed corporate income taxes, accompanied by no sales tax. Delaware also has the smallest shadow economy in the US, on average.

- Reduce or eliminate occupational licensing requirements and other labor market regulatory burdens. Hotels, cabs, beauty salons, and mail delivery services are just a few of the business types that are influenced by occupational licensing in many states. In the formal sector, these industries all profit in a big way from exclusive trade licensing. Unfortunately, such licensing is also responsible for the wasting of many states’ limited resources, as states often focus their task force efforts on squashing the many relatively harmless underground jobs that come to fruition under strict, onerous licensing rules.

- Reduce or eliminate price controls. Minimum-wage hikes primarily serve those who are at present employed in minimum-wage positions; they do little to incentivize employers to hire new labor from the low-skilled labor With the bottom rung of the economic ladder removed, many people entering the labor force for the first time with little experience will turn to the underground economy—and, incidentally, never show up in official unemployment statistics. Rent controls are another form of price control that create perverse incentives for owners of rental properties. Under strict rental pricing regimes, landlords will search for ways to bust through the price cap. Some convert their apartments into makeshift hotel suites – think Airbnb. In this way, landlords earn profits by offering accommodations at prices lower than those charged by legal, licensed hotels, but at higher fixed rents.

- Reconsider prohibitions. Undoubtedly, there is substantial shadow economic activity associated with goods that are outright illegal to produce and consume under any circumstances. The choice to outlaw a good necessarily forces its remaining production and consumption For example, since the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in Colorado, Washington, and other states, consumption and production has become more visible. The good is taxed, and producers and consumers have recourse to the legal system and experience workplace and quality standards that go along with the above-ground economy.32For more details about the impact of marijuana legalization on crime, public health, traffic fatalities, etc., see Jeffrey Miron, Angela Dills, and Sietse Goffard, “Common Myths about Marijuana Legalization,” Cato at Liberty, November 4, 2016, https://www.cato.org/blog/common-myths-about-marijuana-legalization. Also, policy analyst Ashley Bradford and economist David Bradford demonstrate that prescription drug dependency and Medicare program spending are reduced in states that permit medical marijuana use. Ashley Bradford and David Bradford, “Medical Marijuana Laws Reduce Prescription Medication Use in Medicare Part D,” Health Affairs 35, no. 7 (2016): 1230–36.

Conclusion

This chapter introduces the reader to the shadow economy—what it is, what causes it, what can be done to reduce its size—and highlights tax and regulatory environments as determinants of entrepreneurial decisions to do business off the books. Onerous occupational licensing, burdensome tax policies and incentive programs, and outdated prohibitions all work against entrepreneurs by obstructing their path to prosperity. Productive entrepreneurs thrive in places where barriers to market entry are low—where they participate less in the shadow economy and more in the legal sector. This means also that they commit fewer crimes, dedicate less effort toward unproductive rent-seeking activity, and instead focus their efforts on wealth creation. It must be recognized that governments will not pave the path to prosperity with wasteful tax and spending initiatives and burdensome regulation. To expand economic opportunities, we must work to eliminate the government’s role in picking who gets to participate in the market and who doesn’t. Instead, let the free-enterprise system determine that.

References

Baumol, William. “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive and Destructive.” Journal of Political Economy 98 (1990): 893–921.

Bradford, Ashley and David Bradford. “Medical Marijuana Laws Reduce Prescription Medication Use in Medicare Part D.” Health Affairs 35, no. 7 (2016): 1230–36.

Buehn, Andreas and Friedrich Schneider. “Shadow Economies around the World: Novel Insights, Accepted Knowledge, and New Estimates.” International Tax and Public Finance 19 (2012): 139–71.

Buñuel, Luis. My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buñuel (New York: Random House. 1982). 45.

Carpenter, Dick M. II et al. License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing. 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice. 2017).

Carroll, Sidney L. and Robert J. Gaston. “Occupational Restrictions and the Quality of Service Received: Some Evidence.” Southern Economic Journal 47, no. 4 (1981): 959–76.

Cebula, Richard J. and Edgar L. Feige. “America’s Unreported Economy: Measuring the Size, Growth and Determinants of Income Tax Evasion in the U.S.” Crime, Law and Social Change 57, no. 3 (2011): 265–58.

de Soto, Hernando. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (New York: Basis Books, 2000).

de Soto, Hernando. The Other Path: Economic Answers to Terrorism (New York: Basic Books. 1989).

Johnson, Simon, Daniel Kaufmann, and Andrei Shleifer. “The Unofficial Economy in Transition.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, no. 2 (1997): 159–239.

Lacko, Maria. “Do Power Consumption Data Tell the Story? Electricity Intensity and Hidden Economy in Post-socialist Countries.” in Planning, Shortage, and Transformation: Essays in Honor of Janos Kornai (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2000).

Lacko, Maria. “Electricity Intensity and the Unrecorded Economy in Post-socialist Countries.” in Underground Economies in Transition (Farnham, UK: Ashgate. 1999).

Lacko, Maria. “Hidden Economy: An Unknown Quantity? Comparative Analysis of Hidden Economies in Transition Countries. 1989–1995.” Economies in Transition 8, no. 1 (2000): 117–49.

Lacko, Maria. “The Hidden Economies of Visegrad Countries in International Comparison: A Household Electricity Approach.” in Hungary: Towards a Market Economy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 1998).

Miron, Jeffrey and Jeffrey Zweibel. “Alcohol Consumption during Prohibition.” AEA Papers and Proceedings 81, no. 2 (1991): 242–47.

Miron, Jeffrey, Angela Dills, and Sietse Goffard. “Common Myths about Marijuana Legalization.” Cato at Liberty. November 4, 2016. https://www.cato.org/blog/common-myths-about-marijuana-legalization.

Neuwirth, Robert. Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy (New York: Random House, 2011). 117.

North, Douglas. “Institutions.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5, no. 1 (1991): 97–112.

Richardson, Lynda. “Nannygate for the Poor: The Underground Economy in Day Care for Children.” New York Times. May 2, 1993.

Schneider, Friedrich and Dominik Enste. “Shadow Economies: Sizes, Causes, and Consequences.” Journal of Economic Literature 38 (2000): 77–114.

Schneider, Friedrich. “The Shadow Economy and Work in the Shadow: What Do We (Not) Know?” (IZA Discussion Paper No. 6423. Institute for the Study of Labor. Bonn, Germany. 2012).

Sennholz, Hans F. The Underground Economy. Online ed. (Ludwig von Mises Institute. 1984). 10. https://cdn.mises.org/The%20Underground%20Economy_3.pdf.

Sobel, Russell S. “Testing Baumol: Institutional Quality and the Productivity of Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Venturing 23, no. 6 (2008): 641–55.

Stansel, Dean, José Torra, and Fred McMahon. Economic Freedom of North America 2016 (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute. 2016).

Thornton, Mark. “Alcohol Prohibition Was a Failure.” (Policy Analysis No. 157. Cato Institute. 1991).

Wiseman, Travis and Andrew Young. “Economic Freedom, Entrepreneurship & Income Levels: Some US State-level Empirics.” American Journal of Entrepreneurship 6, no. 1 (2013): 100–119.

Wiseman, Travis and Andrew Young. “Religion: Productive or Unproductive.” Journal of Institutional Economics 10, no. 1 (2014): 21–45.

Wiseman, Travis and Andrew Young. “Religion: Productive or Unproductive.” Journal of Institutional Economics 10, no. 1 (2014): 421-33.

Wiseman, Travis. “US Shadow Economies: A State-Level Study.” Constitutional Political Economy 24, no. 4 (2013): 310–35.

Table of Contents

- Regulation and Entrepreneurship: Theory, Impacts, and Implications

- Regulation and the Perpetuation of Poverty in the US and Senegal

- Social Trust and Regulation: A Time-Series Analysis of the United States

- Regulation and the Shadow Economy

- An Introduction to the Effect of Regulation on Employment and Wages

- Occupational Licensing: A Barrier to Opportunity and Prosperity

- Gender, Race, and Earnings: The Divergent Effect of Occupational Licensing on the Distribution of Earnings and on Access to the Economy

- How Can Certificate-of-Need Laws Be Reformed to Improve Access to Healthcare?

- Land Use Regulation and Housing Affordability

- Building Energy Codes: A Case Study in Regulation and Cost-Benefit Analysis

- The Tradeoffs between Energy Efficiency, Consumer Preferences, and Economic Growth

- Cooperation or Conflict: Two Approaches to Conservation

- Retail Electric Competition and Natural Monopoly: The Shocking Truth

- Governance for Networks: Regulation by Networks in Electric Power Markets in Texas

- Net Neutrality: Internet Regulation and the Plans to Bring It Back

- Unintended Consequences of Regulating Private School Choice Programs: A Review of the Evidence

- “Blue Laws” and Other Cases of Bootlegger/Baptist Influence in Beer Regulation

- Smoke or Vapor? Regulation of Tobacco and Vaping

- Moving Forward: A Guide for Regulatory Policy