President-elect Biden’s administration is expected to bring renewed focus and attention to climate change and environmental issues. One policy listed on his campaign website derives from the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The approach focuses on conserving thirty percent of land and water by 2030, with the catchy shorthand “30 by 30”. More than just marketing, the catchphrase is based on recommendations by a growing group of scientists who say that conserving thirty percent of the earth’s land and water is key to preventing biodiversity loss and slowing global warming. That plea from scientists was incorporated into the UN’s sustainable development goals, which outline several targets to be achieved by 2030, to create the “30 by 30” initiative.

The UN target first appeared in a January 2020 draft report from the Convention on Biological Diversity, and aims to protect biodiversity “through protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures.” Since the draft publication, policymakers around the world have advanced proposals to enact the policy in their respective countries. Senator Tom Udall of New Mexico sponsored a resolution a few months before the UN draft was published. While the timeline and key goals are succinct and consistent across UN messaging, the particulars are likely to vary as individual countries work to implement those goals within their unique policy and natural environments, if they decide to at all.

A bold plan for American conservation–Can it be done?

The incoming Biden team has already included the 30 by 30 goal in its “Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution and Environmental Justice” on the campaign website. The particulars of which land the administration will preserve and the policy mechanisms they will use to preserve it are as of yet undecided. But the success of the proposed legislation is likely to hinge on these factors. It’s also reasonable to stop and ask–is this policy politically and physically feasible? Is it an effective way to achieve the stated goals?

Land and water conservation is one of the few things that has garnered bipartisan support over the past couple of years. For example, last year, the Great American Outdoors Act became law, including permanent funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which provides grants to states to pursue conservation projects. Now that Democrats have won a majority in the Senate, it is possible that the 30 by 30 initiative could become law.

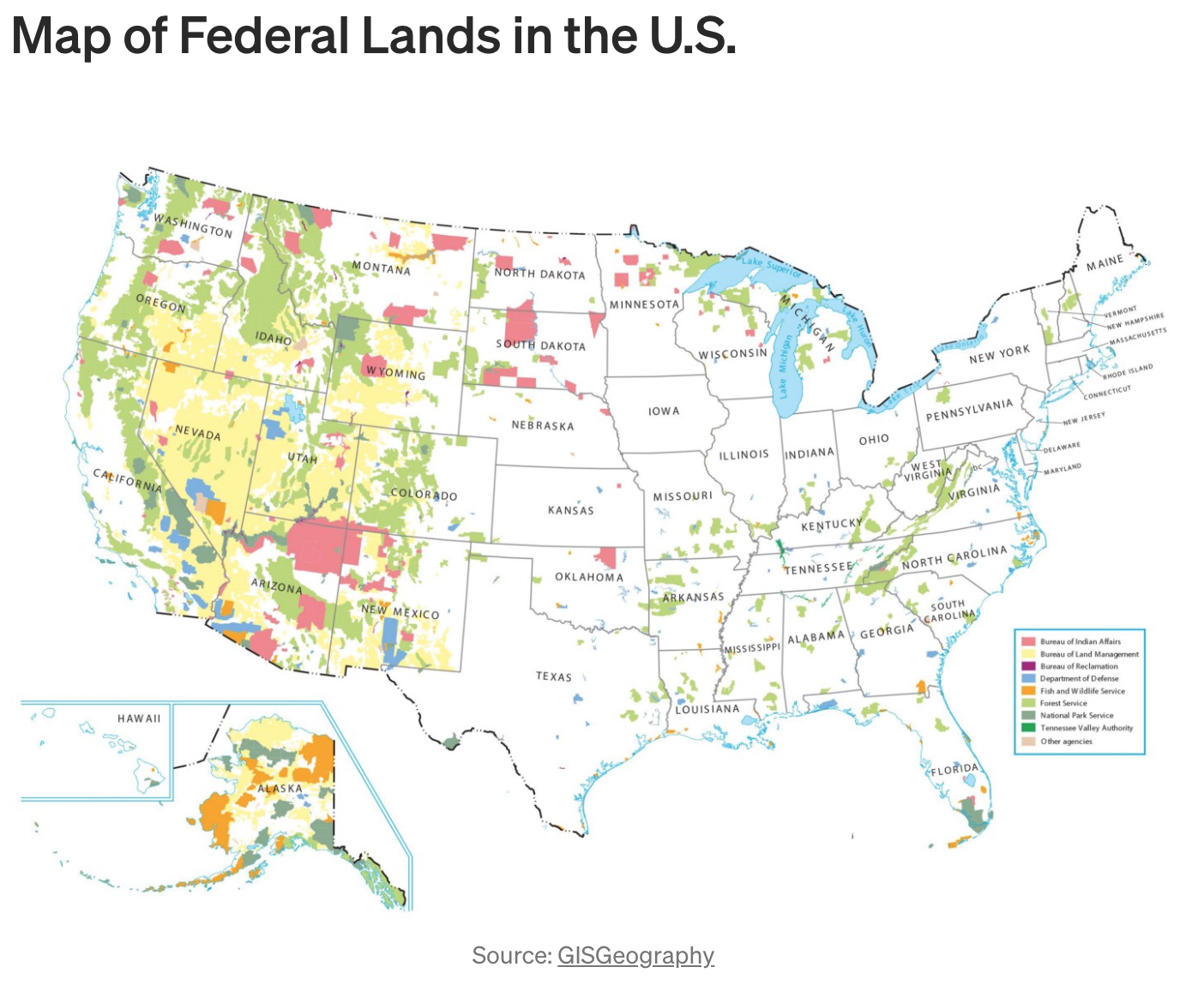

As for physical plausibility, twelve percent of US land area is currently protected through state and national parks, permanent conservation easements, and other protected areas. Twenty-six percent of water is protected, including freshwater rivers and oceanic marine protected areas. Conserving thirty percent of US waters will be easier than preserving an equal percentage of land. However, existing protected areas are currently concentrated in specific regions and ecosystems. For example, as the map of the federal lands below shows, seventy-three percent of Forest Service lands and seventy percent of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) grounds in the US are in the 11 western states, where forty-six percent of all land is federally owned. In the rest of the mainland states, the federal government only owns four percent of land. For water, the vast majority of protected areas are in the far Pacific and offshore Hawaii.

For the initiative to effectively achieve its goals of conserving at-risk ecosystems and fostering biodiversity, more land and water that sits closer to population centers will need to be protected. Figuring out how to preserve large enough swathes of land and water to be ecologically significant while maintaining quality of life for nearby residents will pose a challenge. This highlights the need to bring together stakeholder groups to address climate change and biodiversity loss.

Two resolutions from the upper and lower houses acknowledge that need and provide some insight into how we can expect the initiative to advance in Congress. Biden’s pick for Secretary of the Interior, US Representative Deb Haaland, was a signatory to a 2019 House resolution urging the federal government to develop a national goal to implement the 30 by 30 initiative. Combined with the similar Senate resolution, congressional leaders have signaled some specific policy goals and avenues they hope to enact and identified different stakeholders that will need to be brought to the table. One such group is private landowners.

Engaging private landowners is key to protecting at-risk ecosystems and species

As the Senate resolution acknowledges, private land makes up about sixty percent of the US’s total land area. The resolution includes several objectives, including “increasing public incentives for private landowners to voluntarily conserve and protect areas of demonstrated conservation value”. Public incentives for landowners will be a vital tool in the administration’s effort to conserve land in particular, given two-thirds of endangered species have habitat on private lands. Seventy-five percent of remaining wetlands and eighty percent of grasslands, two at-risk biomes, are located on private land in the US. However, regulatory requirements of the Endangered Species Act, which also seeks to preserve biodiversity, have led to ill will among some private landowners who worry that the efforts will hinder their livelihood and property rights. This has led some private landowners to become wary of participating in federal efforts to conserve land and wildlife.

Despite these concerns and the contentious debate surrounding the ESA, two-thirds of Americans, including a majority of Republicans, say they want the government to do more to combat climate change. A poll from the Center for American Progress found that eighty-six percent of Americans, including seventy-six percent of Republicans support the 30 by 30 agenda. CGO research finds that most private landowners care about conservation and want to be good environmental stewards. Surveyed landowners want to conserve land and wildlife while maintaining control of their private property and supporting their families.

This is where carefully crafted incentive tools like conservation easements, and safe harbor and candidate conservation agreements can help the federal government and private landowners partner to achieve their common conservation goals. These policy tools help recruit private landowners to the federal government’s efforts to conserve species by entering into agreements to improve habitat to an agreed-upon level while allowing for incidental harm to species in the course of regular action. There are strict consequences for harming endangered species, even accidentally. By assuring landowners that they will not be prosecuted for incidental harm to species, federal agencies can get these key stakeholders to protect and enhance critical habitat for at-risk species.

Not all protected lands are created equal

In addition to bringing together diverse stakeholders, Congress will have to make decisions about what protections count toward the thirty percent goal. The UN target included a provision that ten percent of the conserved land and water should be under “strict” protection, although it does not define what that means. There are several different types of protected natural areas in the US that each have different levels of restrictions. For example, national forests allow timber harvest and BLM land allows for grazing permits, but wilderness areas ban all mechanized travel except in cases of emergency.

Whether or not legislators decide to adopt the ten percent strict protection provision, as Congress decides how to pursue this initiative, decisions will have to be made about what activities are allowed on protected lands, and those decisions should be guided by the best available scientific knowledge. Congress will need to determine whether or not stricter land-use regulations actually foster better biodiversity and conservation outcomes and work with biologists and ecologists to match ecosystems to the appropriate level of protection. There are fewer and fewer areas left in the US that can be protected in swathes of hundreds of thousands of acres and we can expect humans and nature to become increasingly intertwined in the coming decades. The level of protection needed will likely vary by location and land type. The regulations governing a remote national monument like Bear’s Ears will probably be different than those governing a protected forest near Philadelphia. And decisions about protection will have to incorporate the activities of humans if we want to preserve the increasing number of ecosystems at risk due to the interactions between humans and the environment.

The 30 by 30 initiative provides a feasible step toward preserving nature and combating climate change that has the potential to attract bipartisan support. But to succeed the initiative will require diverse stakeholders to acknowledge that the way humans interact with their environment has changed dramatically since the first big conservation era of the 1900s. Those changes require the federal government to account for the increasingly intertwined relationship between humans and nature. Instead of simply designating huge swathes of land far from population centers, the government should utilize an array of cooperative policy tools to protect ecosystems and wildlife wherever they are at risk.