Today is Earth Day, reminding us to revisit the environmental progress we’ve made and work to confront the biggest environmental challenges still before us. One of the challenges that the Biden Administration has promised to tackle is conservation — committing to protect 30% of America’s land and water by 2030. This is an ambitious goal as only 12% of land in America is currently considered protected, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

How can we realistically expect to meet that goal in the next ten years? Part of the solution may lie in conservation banking, a market-based approach to habitat preservation that provides an economically feasible route to protect large amounts of land.

Banking on wildlife habitat

Conservation banking allows an eligible landowner to dedicate their land for the preservation of wildlife habitat, and then sell offset credits to developers or other parties whose projects will damage or destroy similar habitat. Landowners enter into a conservation easement with the Fish and Wildlife Service and are then granted credits based on the size and suitability of their land. Project developers can then purchase those credits to mitigate damage that would otherwise violate the Endangered Species Act.

In the case of the Fenner Valley Desert Tortoise Conservation Bank in California, 7,500 acres were set aside in 2015 for the preservation of the desert tortoise and its habitat. Cadiz Inc., the owner of the bank, entered into an easement with the state of California and was then permitted to sell credits to developers in order to mitigate the destruction of desert tortoise habitat. As the largest conservation bank in the United States, Fenner Valley aims to generate zero net loss of habitat for the tortoise. Bank properties are managed by the San Diego Habitat Conservancy, a non-profit focused on habitat management in Southern California, as well as San Diego Zoo Global, a pioneer in conserving and reintroducing native species in the western U.S.

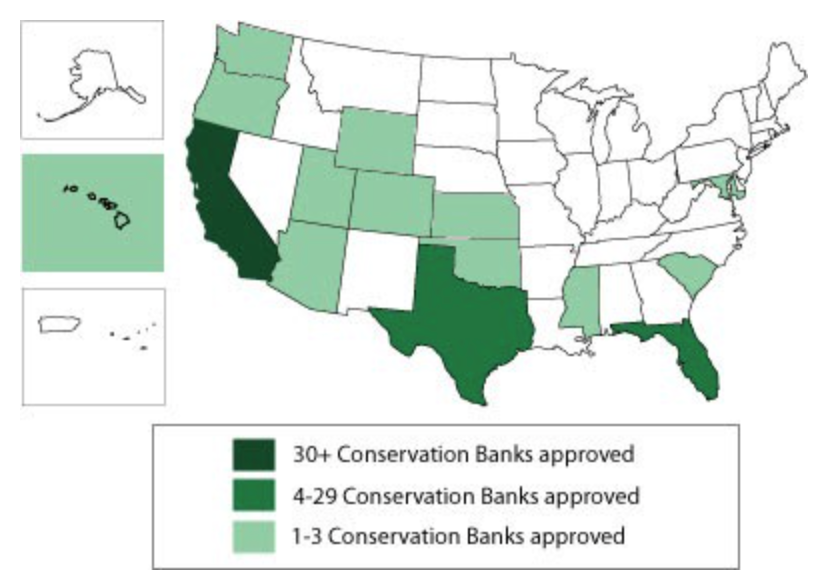

Conservation Banks by State

Source: Fish and Wildlife Service

When do conservation banks work well?

The most successful conservation banks are diligent in species monitoring and conservation efforts to ensure there is no net loss of habitat for a species. Some aim even higher by attempting to achieve a net gain of valuable habitat for the species. The Panther Passage Conservation Bank in Florida is one such successful program. The Florida panther became one of Florida’s most endangered species with only 20 known panthers inhabiting the state in the 1970s. Continued development and habitat destruction pushed the species down the peninsula and threatened their extinction.

In 2007, Les and Jim Alderman noticed the diminishing number of cats and bought 1,930 acres in Hendry County to establish a conservation bank for the protection of the Florida Panther. Motivated by the possibility of financial gain as well as a desire to help the species, the Alderman brothers began their efforts to preserve the land. At the time, there were around 100 panthers in Florida. By 2017, the panther population had grown to about 200 on the peninsula. Through conservation efforts such as vegetation monitoring and panther prey studies, the bank contributed towards the gradual recovery of the native cat.

Another benefit of conservation banking is that it is generally less costly per acre to manage than other mitigation options. Instead of purchasing conservation bank credits, developers also have the more traditional options of purchasing additional land to use as a method of mitigation or paying in-lieu fees. The first approach can be inefficient, as developers have to expend resources to find suitable land and place it under a conservation easement. Through the second approach, developers pay a fee for habitat destruction, which is then used to purchase land as a mitigation offset.

In-lieu fees are generally available for species native to wetlands, however, these programs often do not meet their conservation goals. The Nicholas Institute at Duke University identified important flaws of in-lieu fee programs. They found that these fee programs often fail to increase fee rates equivalent to increasing land prices, lack transparency in record-keeping, and are often not held accountable for fully offsetting the land they permit to be developed. Habitat destruction offset credits offered through conservation banks offer a way around these issues and can also reduce the costs of conservation to developers.

A key benefit of conservation banks is that they create an economic incentive for conservation, as those who start and participate in banks stand to profit financially. When conservation bank owners were surveyed, 91% reported that their chief motivation for starting a conservation bank was financial gain. Conservation banks provide a way to generate profit on land that is otherwise unlikely to be developed. A 2017 study compared the costs and revenues of 18 different conservation banks and found these banks had produced an average of $2.2 million in revenue compared to just $689,540 incurred as costs to maintain the banks. This profitability has spurred the creation of 61 new conservation banks between 2005 and 2016, significantly increasing the amount of land protected under such programs.

Landowners who participate in conservation banks generate income from their land, and they are often eligible for a significant tax break after they enter a conservation easement. All of these benefits suggest conservation banking is one of the most cost-effective ways to mitigate habitat destruction and could be a useful tool in reaching President Biden’s land conservation goals.

Evaluating outcomes for wildlife

While banks such as Panther Passage have contributed towards species recovery, the ecological impact of conservation banking may not be consistent across banks. A common criticism of conservation banking is that the banks cannot clearly measure the effects they have on the species they protect. It is difficult to determine what an equivalent offset is for a development project, and while banks ensure that the amount of land being protected is equivalent to that being developed, they may overlook important ecological factors, such as the difference in species population or habitat quality between the bank and the area being developed.

Current standards outline how conservation banks are to be established and allocate credits based on land size. The Obama administration updated these guidelines in 2016 to include the goal of zero-net loss of habitat, however, the measure was repealed by the Trump administration. Even if they were to be reinstated, the 2016 standards also fail to outline how equivalent offsets should be determined and don’t take into account ecological suitability when assigning credits, making it hard to demonstrate that conservation banking, in general, is ecologically beneficial. Without proper regulation, conservation banks could be failing to achieve their goal of a zero net loss in species population.

The success of conservation banking can also be diminished in areas, particularly wetlands, where developers have the choice between purchasing conservation bank credits or paying an in-lieu fee to the state government. Over time these programs have generally failed to increase that fee equivalent to increases in property values, making it impossible for the state to purchase sufficient land to offset the habitat destroyed. The low price of the in-lieu fee also decreases demand for conservation bank credits which are more accurately priced based on the value of the land they protect. Because in-lieu fees can be much lower than the cost of participating in a conservation bank, they create competition that draws funds away from conservation banking. This may lead to less environmental maintenance than if that money had been invested in a conservation bank.

Policy changes for a brighter conservation future

For conservation banking to be successful both economically and in protecting wildlife habitat, current standards should be updated. First, clarity is needed on how credits are initially allocated when a conservation bank is established based on how valuable that area is for conservation. Second, clear guidelines are also needed to determine how many credits should match up with the area being developed. The goals of each conservation bank are different and the habitat being developed is equally diverse. Despite these differences, a more standardized system for evaluating the ecological impacts of banks and their credits will help decrease ambiguity surrounding their effectiveness in conservation.

Fortunately, the need for increased clarity has been recognized and Congress has ordered the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to create such a system under the National Defense Authorization Act for the Fiscal Year of 2021. The FWS must create and implement the system within one year of the bill being signed, signaling a step in the right direction.

Another way to make conservation banks more successful would be to end in-lieu fee programs, which provide competition that may not lead to environmental improvements. The price of conservation bank credits is determined by the cost of habitat preservation rather than by the government, which sets the price of in-lieu fees. The Nicholas Institute shows that in-lieu fees are often lower than the actual cost of mitigating the damage done by developers. As conservation banking is a more effective method of habitat destruction mitigation than fee programs, the FWS should require that developers purchase bank credits rather than participating in fee programs where bank credits are available.

Banking on the future

Protecting 30% of America’s land by 2030 will require using all the tools in our conservation toolbox. Conservation banks can help make the protection of large amounts of habitat economically feasible. While some issues remain surrounding transparency and accountability for outcomes, coming policy changes are a step forward in making conservation banks a reliable way to protect wildlife habitat. If these policy changes are successful, conservation banks have the potential to be an important tool in reaching our most ambitious environmental goals and creating a more wildlife-friendly future.