Last week, BioNTech and Pfizer announced that their COVID-19 vaccine had shown efficacy in human trials, and this Monday, Moderna did the same. No one was sure this point would ever be reached. Both groups have submitted applications to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency approval, paving the way for the vaccines to be distributed beginning sometime next year. Both are projecting 95 percent effectiveness, far above the threshold of 80 percent required to extinguish an epidemic without any other measures like social distancing.

Since the first discovered case in the U.S. in January of 2020, COVID-19 has left entire industries beleaguered, and continues to tighten its stranglehold on the global economy. At the same time, the crippling effect of COVID-19 has rallied an army of talented and courageous healthcare professionals into action, creating a global coalition of governments, companies, health institutes, and research groups to find solutions. Researchers have pursued over 200 potential candidate vaccines, and narrowed the number of viable vaccine candidates down to just five in record time.

Political wranglings by President Trump injected unnecessary confusion into the process. While the White House pushed its own desired coronavirus timeline, vaccines were always going to be governed by the development process and efficacy requirements of the FDA. However, the White House has been key in shifting cost burdens and eliminating uncertainty through Operation Warp Speed, which was funded through the CARES Act.

Polling shows there will be challenges ahead in convincing the public that vaccines are safe and effective. The speed of development comes from three factors. First, vaccine developers had a head start on research because of SARS. Second, new vaccine technologies have been debuted, which has significantly shortened development times. Finally, the failure to stop the spread of COVID meant that human trials would progress swiftly.

Polling, and the public policy problems ahead

According to Morning Consult, which has been polling 2,200 U.S. adults weekly since February, public sentiment regarding a vaccine has soured. In February, when participants were asked whether they would take a vaccine if it were made available, 72 percent of adults said they would. Fast-forward nine months to November and the number of adults that say they would take a vaccine if available now stands at only 49 percent. Nearly a quarter of Americans have changed their minds.

Global comparisons of vaccine adoption polling are equally alarming. In 2019, the U.S. was the second most accepting of vaccines, according to Ipsos MORI. Now, the U.S. has fallen behind, down to just 63 percent from its 2019-level of 80 percent. Global sentiment is similarly pessimistic. Great Britain, Italy, and France experienced roughly 10 percent declines in the percent of citizens willing to take a vaccine. Even still, faith in medicine has hardly budged according to that same poll.

Bernice L Hausman’s book, Anti/Vax: Reframing the Vaccination Controversy, provides valuable insights into why a person would reject a life-saving vaccine. Among other concerns, Hausman found that resistance was driven by:

- belief in the value of natural illness;

- desire to avoid unnecessary medicine and treatment;

- alternative views about health and medicine;

- lived experience with illness, especially with illness that is not effectively treated by mainstream medicine;

- protection of the body and control over what goes into the body;

- experience with perceived vaccine injury;

- distrust of mainstream scientific studies of vaccine safety; and

- distrust of medicine’s entanglement with big business (especially “Big Pharma”) and government.

The likely culprit for swift declines across a range of countries is some combination of lived experience with the illness, distrust in the entanglement of pharmaceutical companies and the government, low faith in government’s ability to manage vaccine production in light of its mismanagement of the crisis, and uncertainty about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines. The new normal is just muddling through.

Why so fast? Covid vaccine development

Bringing a vaccine to market typically takes ten to fifteen years, which is why the timeline for COVID-19 vaccine development is all-the-more impressive. Not surprisingly, worries have flared up about the efficacy of vaccines that have been developed nearly ten times faster than normal.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), vaccine development can be broken up into six stages, including:

- Exploratory Stage;

- Pre-clinical stage;

- Clinical development;

- Regulatory review and approval;

- Manufacturing; and

- Quality control.

As Mitchell, Philipose, and Sanford relay in The Children’s Vaccine Initiative: Achieving the Vision, vaccine development stages are not so neatly divided in practice. Basic research, which is considered part of the exploratory stage, continues to inform the process of development even during clinical testing. Likewise, findings at the manufacturing and clinical stages feed observations and questions back to basic research.

Researchers had a massive head start on the Covid vaccine because the 2003 outbreak of SARS led to a surge in vaccine research. Covid is remarkably similar to SARS in that both have spike proteins, so the research community easily built on that prior work.

Development times have also been compressed because mRNA vaccines, a new type of vaccine, are being debuted. To elicit an immune response, most antigens deliver a dead or weakened version of the pathogen. An mRNA vaccine bypasses this process and delivers the instructions directly to the cells to produce the antigen. The mRNA method has important benefits, namely that vaccines can be developed and manufactured much faster than the traditional method. Instead of the normal timeline of 2 to 4 years, the exploratory stages for both Pfizer and Moderna were completed in less than 10 weeks.

The second stage, known as the preclinical stage, can take anywhere from 1 to 2 years. In this stage, researchers will test for an immune response, explore safe dosages, and understand how to administer the vaccine by exposing the candidates to tissue-cultures, cell-cultures, or animals, such as mice and monkeys. Yet again, because of the experience with SARS and the inherent benefits of mRNA vaccine tech, promising vaccines quickly moved through the process.

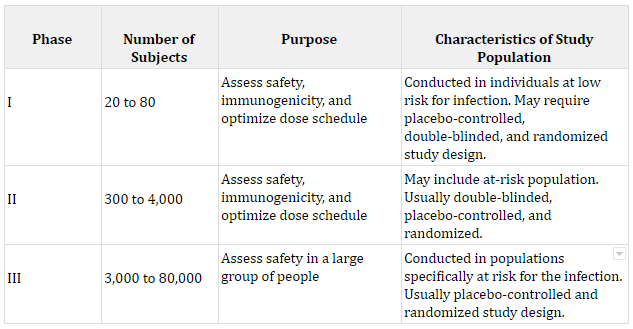

After the preclinical stage, vaccines then undergo Phase I human trials, the first part of the clinical stage. Phase I focuses on the general safety of the vaccine, dosaging, and the response effect known as immunogenicity on a small population of health individuals. Candidate vaccines were ushered through Phase I trials at breakneck speed. Promising vaccines might take anywhere from 3 to 9 years to get through the first stage of human trials, but the combination of new technology, prior experience, and worldwide demand pushed this down to 6 months.

If a candidate vaccine makes it through Phase I, the number of subjects is expanded for Phase II, and again safety, dosage, and immunogenicity is examined. Finally, in Stage III the trial’s total participant pool is expanded to understand safety. The table below dives into more details about each of the phases. Many COVID vaccines are somewhere around stages II and III, which can be tracked by the Milken Institute.

Sources: The number of subjects was calculated by the author from a sample of previous vaccine trials. Each purpose comes from The History of Vaccines.

The nature of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that human trials would progress quickly. Fundamentally, clinical trials test a hypothesis about vaccine efficacy, which is dubbed the primary efficacy endpoint. Once the primary endpoint is selected, a sample size can be calculated to ensure the trial is properly powered. For COVID-19 vaccines, researchers have been looking for a set number of infections.

A grisly calculus then ensues. As more of the population gets sick with the disease, the potential vaccine racks up more cases to reach its endpoint. In contrast, diseases that progress slower, like cancers, will be in clinical trials for years because it takes that long to reach the primary efficacy endpoint. The recent increase in COVID-19 cases advanced everyone’s timetable. As one report noted, Pfizer had expected to reach its 164 case efficacy point in December, but was in a position to release the data earlier because of the surge. As Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla said, “The election was always, for us, an artificial deadline. It may have been important for the president, but not for us.”

Shifting the risk burden

While the Trump Administration hasn’t been involved in moving timelines, it has been key in shifting cost burdens and eliminating uncertainty through Operation Warp Speed (OWS), which is administered by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Developing a vaccine and taking it through human trials isn’t cheap, and over time, these costs have increased. Companies limit their financial risk of drug development by spreading the costs over consecutive years and completing stages in sequence.

OWS has compressed the time to market by providing assistance at key points in the development process to 14 promising drugs. Starting in March, the OWS program began doling out its $10 billion allocation to support research by a number of big name companies like:

- Johnson & Johnson;

- AstraZeneca–University of Oxford and Vaccitech;

- Moderna;

- Novavax Inc.;

- Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.;

- Merck and IAVI;

- Novavax; and

- Sanofi and GlaxoSmithKline.

OWS has also been working with these companies and others to start the manufacturing process at industrial scale well before the demonstration of vaccine efficacy and safety. This move is risky. If a vaccine that has already been mass-produced is deemed unsafe, it will be thrown out, resulting in a serious financial loss to the government.

Moreover, OWS has guaranteed that it will buy a set number of vaccines. Indeed, while Pfizer wasn’t involved in direct research assistance, they have entered into a contract with the government for 100 million doses. One study of these purchase agreements suggests that $110 billion in targeted funds will generate net benefits of $2.8 trillion, nearly double the baseline. All of these actions increase financial risk, which is shifted to the government, but not the product risk.

Beyond funding, OWS coordinated efforts to ensure that companies knew exactly what the FDA would need to give a vaccine the go ahead. In June, the FDA released guidance and said they were looking for at least 50 percent efficacy in drugs, with a lower bound of 30 percent. By way of comparison, flu vaccines average around 67 percent effective. Both Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech have blown this out of the water with 95 percent effectiveness. These results are incredibly heartening, since 80 percent effectiveness would “largely extinguish an epidemic without any other measures (e.g., social distancing).”

Conclusion

Moving forward, leaders should work to dispel myths around COVID-19 vaccines. Safety and efficacy aren’t being sacrificed. Rather, the rapid pace of progress comes from innovations that have been in the works for decades backed by strategic investments by the government. While the United States is far from snuffing out this virus, the last year has shown that cooperation among private and public sector actors, especially in times of crisis, is the key to solving critical problems.