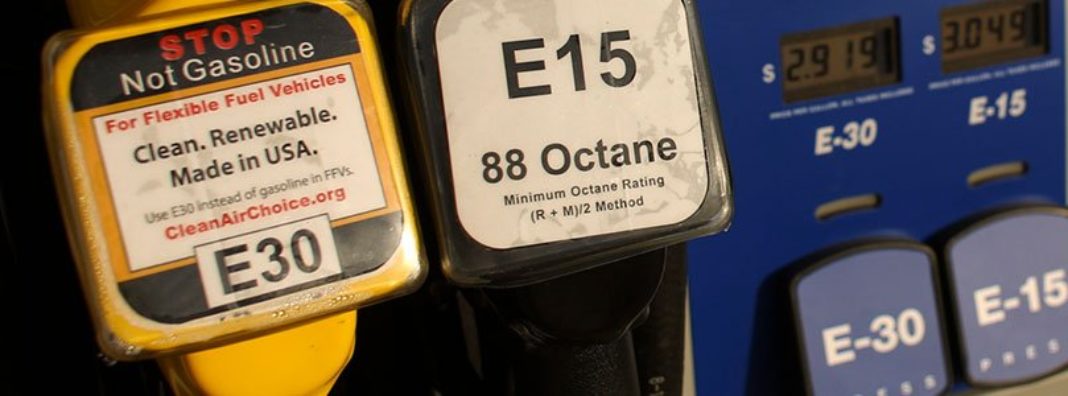

On March 12, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed a new rule to allow the year-round sale of E15 fuel, a gasoline mixed with biofuel produced from corn. The ethanol industry trumpeted these changes as a boon to the environment, arguing that gasoline with ethanol added will clean up emissions from transportation fuel.

Yet despite decades-old industry promises that ethanol cleans up emissions, research shows these claims don’t hold true. Ethanol’s use can be beneficial in a variety of areas, but the federal mandate far overextends those uses. Instead of protecting the environment, the current ethanol mandate is causing a considerable amount of environmental blowback.

New research from the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) by researchers at three universities is the most recent in a long list of evidence showing that the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) are harming the environment. Because the RFS created a huge incentive to grow more corn, farmers began overusing fertilizers and moving into environmentally-sensitive areas. As Dr. Aaron Smith from the University of California, Davis, summarizes, “The ensuing expansion and intensification of crop agriculture has transformed the landscape, leading to a cascade of negative impacts on wildlife habitat, water resources, and the climate.”

It’s important to point out that these effects aren’t inherent in ethanol production or in corn farming. Rather, it’s an outsized government mandate that pushed corn production out of areas well-suited for growing corn. Rather than benefiting the environment as proponents intended, the Renewable Fuel Standard has incentivized environmental degradation.

Land use changes encouraged by the ethanol mandate clearly show the effects of these bad incentives. For example, the NWF reports that “1.6 million acres of grassland, shrubland, wetland and forestland [were converted] into cropland between 2008 and 2016,” because of the RFS. That’s only the beginning, however, as “an additional 1.2 million acres of cropland remained in production instead of being retired to pasture or retired through farm conservation programs.”

Those land use changes also create substantial carbon dioxide emissions, 27 million metric tons — as much as seven coal plants — according to the NWF’s research. And those emissions won’t be offset by cleaner fuel. A review of studies on how much ethanol reduces greenhouse gas emissions published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics showed that mixing ethanol with gasoline does practically nothing to reduce emissions. In fact, ethanol is even worse than gasoline when it comes to ozone emissions.

The Trump Administration’s pursuit of more ethanol is concerning because it’s doubling down on a failed policy that will make today’s environmental problems worse, not better. As Arthur R. Wardle, a graduate research fellow at the Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, wrote about his own research on RFS, “A multibillion-gallon mandate needs strong justification, but the environmental record for corn-based ethanol provides just the opposite.”

In place of the RFS’s mandate for corn ethanol and expanded ethanol sales, policymakers should be removing requirements that ethanol be produced in the first place. Since the RFS was passed in 2005, this year marks 15 years of titanic public support for the ethanol industry. In that decade and a half, the environment has only lost out. It’s time that ethanol stand on its own.

Real Clear Energy

Real Clear Energy