The introduction of COVID-19 has moved markets and sparked incredible changes in civil society and at federal agencies. But there is disagreement about whether or not official institutional responses have been effective and well-timed. Mark Lutter, founder and executive director of the Charter Cities Institute, chided the response, saying, “A functioning government could have prevented the crisis, as Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have demonstrated. Aggressive testing and early social distancing kept their caseloads low and limited exponential growth.”

As South Korea and Singapore show, early and aggressive testing in the United States could have lessened the severity of this pandemic. At a minimum, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) erred in not trusting local hospitals and labs to do high-quality testing. They should have quickly expanded testing through public and private means to understand the spread of the infection as soon as they learned of problems in the CDC’s tests.

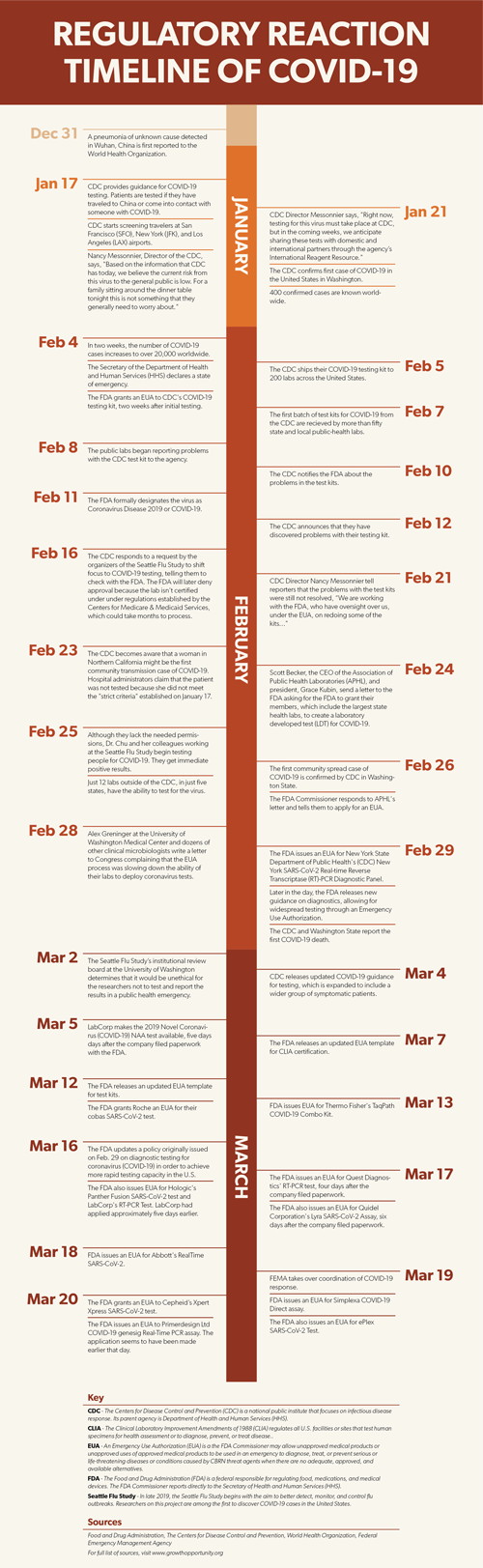

In the following condensed timeline of the frictions caused by the regulatory state, it is clear that workers on the front line, public health officials, clinicians, and leaders at all levels of government were stymied by regulatory hoops and knowledge problems. While testing has expanded massively in recent weeks, the confusion throughout February caused a holdup, an expected outcome of regulatory uncertainty. The cumulative effect led to a further spreading of the disease that could have been prevented.

Source: Center for Growth and Opportunity

The impact of CDC guidance

The coronavirus crisis began at an auspicious time on the last day of 2019, December 31, when a case of pneumonia of an unknown cause was first reported to the World Health Organization. While it is clearly the case that Chinese government officials knew about the first cases and tried to suppress reports, the virus reached the United States on January 15.

On January 17, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) took three actions. First, they acknowledged the existence of the novel coronavirus. Later, the CDC would name the virus as SARS-CoV-2 and the disease that accompanies the virus COVID-19. Next, they laid out guidance for COVID-19 testing. To be considered, a patient needed to have a fever and symptoms of lower respiratory illness like a cough or shortness of breath as well as either a history of travel from Wuhan, China, or close contact with a person who is under investigation for the virus. Speaking on a telebriefing, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC, says that, “Based on the information that CDC has today, we believe the current risk from this virus to the general public is low. For a family sitting around the dinner table tonight, this is not something that they generally need to worry about.” As a third measure, the CDC started to screen travelers at San Francisco (SFO), New York (JFK), and Los Angeles (LAX) airports that were coming from Wuhan.

Strict testing criteria created myopia since it didn’t recognize other sources of infection. For example, a woman in Northern California who later found out she had the coronavirus was delayed in getting a test largely because she got infected through an unknown source. The testing guidance didn’t account for this kind of risk, which is known as community spread. In a memo, hospital administrators at the UC Davis Medical Center explained what happened next,

We requested COVID-19 testing by the CDC since neither Sacramento County nor CDPH is doing testing for coronavirus at this time. Since the patient did not fit the existing CDC criteria for COVID-19, a test was not immediately administered. UC Davis Health does not control the testing process.

Only the CDC’s test had been approved by the FDA at this point, so the guidance became a hard rule. Patients who didn’t check off the right boxes were not tested. A nurse working on the frontlines in California faced similar obstacles,

When employee health told me that my fever and other symptoms fit the criteria for potential coronavirus, I was put on a 14-day self-quarantine. Since the criteria was met, the testing would be done. My doctor ordered the test through the county.

The public county officer called me and verified my symptoms and agreed with testing. But the National CDC would not initiate testing. They said they would not test me because if I were wearing the recommended protective equipment, then I wouldn’t have the coronavirus.

By February 1, the CDC expanded criteria to include travelers from Hubei province, not just Wuhan. Then on February 28, the CDC further extended its guidance to include people who were hospitalized for respiratory illness, regardless of travel history. Finally, on March 5, the CDC released guidance that put doctors in charge and deferred to their judgment in testing.

Still, the impact of CDC guidance is hard to summarize since they don’t set policy. Public and private hospitals sometimes adopt CDC guidance as their official policy, and other times they will follow state guidance or guidance set out by an applicable trade association. In San Diego, Scripps Health offers drive-through testing, but only for those patients with a referral. To get a referral, a patient would have to be a healthcare worker, first responder, have an underlying condition, or be an older person living in a group home. These criteria are in line with guidelines provided by the Association of Public Health Laboratories. Other testing sites in the San Diego area following CDC guidelines instead. The New York City Health Department has directed doctors only to order tests for patients in need of hospitalization, which is more narrow than official CDC guidance. In practice, local protocols have tended to reflect the availability of tests.

CDC test kits narrowly restricted testing

On January 10, researchers from China first released the genetic sequence of the novel coronavirus. They followed up on January 12 with further genomic sequences. According to official CDC data detailed below, the CDC was able to test for the virus on Saturday, January 18, making it one of the first countries outside of China to be able to detect the virus. That next Tuesday, January 21, CDC Director Nancy Messonnier announced the test in a telebriefing, “Right now, testing for this virus must take place at CDC, but in the coming weeks, we anticipate sharing these tests with domestic and international partners through the agency’s International Reagent Resource.”

Source: The CDC

The testing method that the CDC chose to pursue comes a high rate of false negatives. The CDC classifies these tests as high complexity, which means that the labs performing them must follow the most stringent rules. Just like any other product, the test faced a scaling-up problem. The CDC needed to produce a high volume of high-quality products. There was a high probability of failure. As Marion Koopmans, head of viroscience at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam and a member of the crew that developed the Berlin test, explained to Nature, “If you scale up fast that may happen.”

Eighteen days after that first CDC test, on February 5, the agency shipped their COVID-19 testing kit to 200 labs across the United States, after being granted an Emergency Authorization Use by the FDA. Two days after that, on Friday the 7th, the labs begin receiving the test kits. The next day, a Saturday, the public labs began reporting problems to the CDC about the test. On Monday the 10th, the first business day after tests indicate problems, the CDC notified the FDA, and on Wednesday, the agency announced to the public that they had discovered problems with their testing kit.

The CDC even botched this first tranche of tests since they were distributed in roughly equal proportions to each of the CDC labs, as Kaiser Health News reported. One woman in South Dakota with mild symptoms and no fever easily got the test and her results. In Missouri, public health officials have had the luxury of time to plan a response. According to infectious disease expert Dr. Steven Lawrence of Washington University in St. Louis, “This is very similar to 1918 with the influenza pandemic — St. Louis had more time to prepare and was able to put measures in place to flatten the curve than, say, Philadelphia.” St. Louis’ quick reaction in 1918 kept deaths down. With only 800 tests on hand at the beginning of February, however, the cities of New York, Boston, Seattle, and the San Francisco Bay Area limited testing and struggled to understand the state of public health.

Experts began sounding the alarm as this was transpiring. On February 4, the Wall Street Journal published an op-ed that called for the FDA to open up testing, written by Luciana Borio, a former director of medical and biodefense preparedness policy at the National Security Council, and Scott Gottlieb, a former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration. Major clinics and labs already had the means to test, Borio and Gottlieb point out, they just needed approval from the FDA. Both Australia and Singapore, who relied on public and private laboratories to produce tests quickly, showed that testing could easily be broadened.

A week after it was announced that the tests were faulty, Nancy Messonnier at the CDC told reporters that the issues have not yet been resolved. The New Yorker quoted her as saying, “We are working with the FDA, who have oversight over us, under the [Emergency Use Authorization], on redoing some of the kits.” She continued, “We obviously would not want to use anything but the most perfect possible kits, since we’re making determinations about whether people have COVID-19 or not.” The CDC had to produce a high-quality test for it to detect the virus properly. It would be another week, on February 26, until the CDC tests were operational.

While the CDC was working on improved tests, the FDA faced significant pressure to open up testing. On February 29, changes in the rules allowed labs and pharmaceutical companies to detect the virus. Testing soon exploded, and the CDC never became a major source for testing. At its peak, CDC labs tested a maximum of 311 patients per day. Instead, U.S. public health labs conducted the majority of testing into early March, as the chart below shows.

Source: The CDC

Even though the CDC had some of the first available tests, the rollout was botched. South Korea and Germany offer a vision of what could have been. South Korea detected its first case on the same date as the United States: January 20. The first week of February, about the same time that the CDC was getting approval for their testing kit, South Korea fast-tracked a company’s diagnostic test, and another soon followed. South Korea wanted to expand production to test on a mass scale, which they coupled with draconian measures like GPS-enabled app monitoring. The effect is that the virus stopped spreading, keeping deaths to a minimum, while cities have remained open. Germany chose a slightly different path. It also deployed mass testing but relied on extensive contact tracing to find and break chains of infection.

Using just the CDC was a risky supply choice by FDA. But the critical moment of hesitation came on Monday, February 10, when the FDA reacted to news of faulty tests by continuing to work with the CDC. Testing supply should have been diversified towards public and private groups. Eventually, this happened on February 29 after significant pressure. While there are some calling for the United States to repatriate critical supply chains, testing could have been easily expanded. As the next section helps to explain, it was the initiation of the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) that added yet another layer that made their testing more difficult.

The regulation of diagnostic tests and the impact of Emergency Use Authorization

Diagnostic testing is regulated through one of two paths. Tests, which are formally known as in vitro diagnostic (IVD) devices, can be developed and distributed as commercial “kits”. Or they can be developed, validated, and conducted by a single laboratory. Tests of the second type are known as laboratory-developed tests or LDTs.

Regulation of both kits and LDTs has been fraught with controversy because Congress has never given the FDA explicit authority to act. Instead, the FDA claims authority over tests by lumping them in with medical devices under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act (FDCA) and the Public Health Service Act (PHSA). Labs face additional certification by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA). The long-standing tensions in authority and regulation over these tests only heightened the problems in February.

In 2012, Congress gave the FDA a deadline to act on LDTs, and in 2014, the agency officially notified Congress of its intent to regulate through draft guidance. The framework laid out three classes of LDTs. Some LDTs would be exempt from regulation entirely, while others would be required to meet notification and adverse event reporting requirements. The third class of LDTs would face the highest scrutiny and would be required to meet notification and adverse event reporting, as well as premarket review, and quality system regulation requirements. However, in January 2017, the FDA released a discussion paper and said it would not be finalizing guidance and instead kicked the issue back to Congress to clarify.

The current regime is punctuated by three opposing forces. Officially, the policy at the FDA is that tests are subject to broad FDCA regulations, which means that they need to be granted an FDA clearance letter or premarket application (PMA) approval and are subject to a range of post‑market requirements. In practice, however, the FDA has done little to force companies to comply with these guidelines, though they have sent hospitals and lab companies warning letters, claiming that they retain enforcement authority. Undercutting all of this, the Supreme Court ruled in Azar v. Allina that informal guidance like a warning letter has little authority unless it is aligned with formal rulemaking.

In the thirty years that diagnostic tests have been available, the FDA has flexed this authority only sparingly. Yet, last year the Food and Drug Administration seemed to suggest a change in direction when they sent a warning letter to Inova Genomics over their MediMap test, which predicts medication response. In the letter, they put the industry on notice, saying,

FDA has not created a legal ‘carve-out’ for LDTs such that they are not required to comply with the requirements under the Act that otherwise would apply. FDA has never established such an exemption. As a matter of practice, FDA, however, has exercised enforcement discretion for LDTs, which means that the FDA has generally not enforced the premarket review and other FDA legal requirements that do apply to LDTs. Although FDA has generally exercised enforcement discretion for LDTs, the agency always retains the discretion to take action when appropriate, such as when it is appropriate to address significant public health concerns.

As one industry commentator explained, “the agency’s official position is that clinical laboratories are serious and persistent lawbreakers, absolved only by the agency’s grace.” But the agency hasn’t granted hospitals grace when it comes to complex viral tests. When Zika hit the southern United States, for example, the FDA sent out letters to two laboratories and two Texas hospitals for marketing high-risk unapproved diagnostics. FDA letters are few and far between for diagnostic tests, but the agency has acted in these emergencies.

Thus, when the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) declared a state of emergency on January 31, 2020, running a test became all that riskier. Declaring an emergency gives the FDA the ability to grant emergency use authorization, or EUAs, to fast-track vaccines, antivirals, and diagnostic tests. In practice, the emergency authority signaled to labs and hospitals that diagnostics tests would be carefully scrutinized. Labs now needed an EUA letter to run tests that were not regulated in a non-emergency. In other words, the EUA process made testing more difficult at the exact moment when more tests were needed. As Turna Ray reported in Modern Healthcare, lab professionals were hesitant to launch LDTs because of the sordid history at the FDA. Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, told Reuters, “Paradoxically, it increased regulations on diagnostics while it created an easier pathway for vaccines and antivirals.”

These problems were felt most acutely by two groups of researchers at the University of Washington, the epicenter of the outbreak. The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the United States was pinpointed to Washington State on January 21. By happenstance, researchers at the University of Washington, private funders, and public health officials were collaborating on the Seattle Flu Study, a program begun in late 2019 to track flu over an entire season. Leaders knew they could have easily shifted testing for coronavirus, but they needed approvals from countless sources, which proved daunting.

According to a New York Times report, sometime after February 10, Dr. Lindquist, the lead epidemiologist in Washington State and a collaborator in the study wrote an email to Dr. Alicia Fry, the chief of the CDC’s epidemiology and prevention branch, asking to use the study to test for the coronavirus. On February 16, Gayle Langley, an officer at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, wrote back saying, “If you want to use your test as a screening tool, you would have to check with FDA.” When the Flu Study turned to the FDA, they also rejected the lab’s test because the lab wasn’t CLIA certified, a process that could take months.

Meanwhile, another lab at the University of Washington Medical Center, run by Alex Greninger, submitted an electronic request to the FDA for a preliminary EUA to test for the novel coronavirus through an in-house LDT on February 18. But the FDA didn’t even look at his application until he overnighted hard copies of the application. On February 24, the FDA came back with guidance and a list of further actions. Among other changes, the FDA wanted Greninger to use his test on MERS and SARS viruses, which are also coronaviruses. Greninger reached out back to the CDC to help source those viruses and they politely turned him down since the material was extremely dangerous and highly restricted. “That’s when I thought, ‘Huh, maybe the FDA and the CDC haven’t talked about this at all,’” Greninger told GQ. He continued, “I realized, Oh, wow, this is going to take a while, it’s going to take several weeks.”

On February 28, Alex Greninger and dozens of other clinical microbiologists wrote a letter to Congress complaining that the EUA process was slowing down the ability of their labs to deploy coronavirus tests. “Many of our clinical laboratories have already validated [tests] that we could begin testing with tomorrow, but cannot due [to] the FDA EUA process,” they wrote. They weren’t the only ones pressuring the FDA. The following day, February 29, the FDA released new guidance on diagnostics, allowing for widespread testing through an Emergency Use Authorization. According to one estimate, about five thousand virology labs in the country immediately qualified to test for COVID-19.

Once the policy changed, the FDA began then approving commercial test kits within four to six days of application submission. For example,

- The FDA issued an EUA for LabCorp’s RT-PCR Test on March 16. The approval likely took five days.

- On March 17, the FDA issued an EUA for Quest Diagnostics’ RT-PCR test, four days after the company filed paperwork.

- Also, on March 17, the FDA issued an EUA for Quidel Corporation’s Lyra SARS-CoV-2 Assay, six days after the company filed paperwork.

Mid to late February was a critical time, and it is clear that regulatory uncertainty made everyone’s job that more difficult. Speaking to Modern Healthcare, Gail Javitt, a director at Hyman, Phelps & McNamara who specializes in FDA regulation, noted that “One of the problems of not having clarity upfront about whether an agency has authority to or will in fact regulate an industry is that it creates confusion, both within the government and by regulated entities, about who is or should be taking the lead, which prevents both industry and regulators from being nimble.”

Knowledge asymmetries as friction points

Knowledge gaps also plagued responses. For one, overlapping agency jurisdictions left practitioners and organizers confused. Most of the labs had been working intimately with the CDC and likely assumed that it was the source of permission for testing, but that task is overseen by the FDA. As noted earlier, Dr. Lindquist in Washington State sent the CDC leadership an email on February 10, asking for permission to test, even though it was the FDA’s approval that they needed. The six-day delay in response could have been avoided if everyone knew the lines of authority better.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo also chided the CDC in early March when he spoke at the Northwell Health Labs, a private laboratory on Long Island. As he explained, “The CDC has not authorized the use of this lab, which is just outrageous and ludicrous.” He went on to say that seven other labs in the state could begin testing immediately for the coronavirus if given federal approval. But again, the FDA, not the CDC, grants approvals for emergency use.

The emergency use process wasn’t widely understood either, even by those who work in this space. Scott Becker, CEO of the nonprofit Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL), was stunned when he learned of it, saying, “We didn’t know about the EUA process. I didn’t really know that we could do such a thing.” Once he was made aware of the process in correspondence from the FDA, he disseminated that information to his member labs, including New York State. In turn, they soon filed an EUA for the test developed by the Wadsworth Center, the state public health laboratory, on Friday, February 28. The next day, the FDA approved the test. A week and a half later, the FDA expanded the EUA to allow the Wadsworth Center to authorize laboratories that used its test.

Confusion over the regulatory regime and a lack of knowledge led to delays in testing. While some might see this as unexpected, economic research stemming from Robert Pindyck’s pioneering 1990 paper suggests such an outcome. As Pindyck surmised, regulatory uncertainty often manifests as product delay. Regulation imposes costs, so in a state of regulatory uncertainty, the total amount of costs are similarly uncertain. One rational move to this uncertainty is to delay a product launch. Labs and private companies did what was expected; they held off testing until there was clarity in the law.

Conclusion

The regulatory thicket created management difficulties for health care workers at the epicenters of the contagion. Especially for those early moments of the crisis which occurred throughout January and into February, it is important to study how institutions, hospitals, and health care workers adapted to the constraints imposed by regulation. These civil society groups were also hamstrung by their own knowledge problems. Altogether these conditions disincentivized coordination at the moment it was needed. In part, some of the confusion was unavoidable. At the same time, countries like South Korea and Singapore show that testing can be expanded quickly. Once this current crisis has passed, leaders should take the time to carefully assess emergency powers and ensure they can run smoothly when we need them most.