Introduction

The Universal Service Fund (USF) was established by Congress as part of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, although its origins date back to rules applied to the old AT&T telephone monopoly, whereby surcharges were added to long distance telephone service to subsidize the build-out of telephone lines to rural areas.1Report, In the Matter of Report on the Future of the Universal Service Fund, FCC 22-67, WC Docket No. 21-476 (2022). Rules implementing Section 254(b) were established in Federal-State Joint Board on Universal Service, CC Docket No. 96-45, Report and Order, 12 FCC Rcd 8776, (1997) (Universal Service First Report and Order). Codified in Section 254(b),247 U.S.C. § 254(b). the USF pays for “‘advanced telecommunications and information services,’ particularly high-speed internet access, for schools (as well as for libraries and rural health care providers).”3See City of Springfield v. Ostrander (In re LAN Tamers, Inc.), 329 F.3d 204, 206 (1st Cir. 2003) (quoting 47 U.S.C. §§ 254(b)(6), (h)(1)). Section 254(b) sets forth priorities for universal service: (1) Quality services should be available at just, reasonable, and affordable rates; (2) Access to advanced telecommunications and information services should be provided in all regions of the Nation; (3) Consumers in all regions of the Nation, including low-income consumers and those in rural, insular, and high cost areas, should have access to telecommunications and information services, including interexchange services and advanced telecommunications and information services, that are reasonably comparable to those services provided in urban areas and that are available at rates that are reasonably comparable to rates charged for similar services in urban areas; (4) All providers of telecommunications services should make an equitable and nondiscriminatory contribution to the preservation and advancement of universal service; (5) There should be specific, predictable and sufficient Federal and State mechanisms to preserve and advance universal service; and (6) Elementary and secondary schools and classrooms, health care providers, and libraries should have access to advanced telecommunications services. See Universal Service First Report and Order, ¶ 42. The USF currently has an annual budget of approximately $8 billion, spread across four programs (High Cost, Lifeline, Schools and Libraries [so-called E-rate], and Telehealth).4See 2021 USAC Report to Congress, https://www.usac.org/wp-content/uploads/about/documents/annual-reports/2021/2021_USAC_Annual_Report.pdf. The USF is funded through contributions made by carriers, which are almost always passed down to consumers. Section 254(d) limits the contribution base of USF to “interstate telecommunications services.”547 U.S.C. § 254(d). See Comments of TechFreedom, In the Matter of Report on the Future of the Universal Service Fund, WT Docket No. 21-476 (Jan. 18, 2022), https://techfreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/TF-Comments-USF-NOI-1-18-22.pdf.

The way in which the FCC has chosen to implement Section 254, however, has led to many serious due process concerns, as documented below. Because the Commission has chosen to delegate almost all aspects of the Fund’s operation to a private entity whose budget comes from both the contributions made by carriers and from monies recouped through audits, the system is ripe for abuse. This paper attempts to quantify that significant problem.

The Commission Has Subdelegated Operational Authority for the Universal Service Fund to a Private Entity

In adopting rules to implement Section 254(b), the FCC’s 1997 Order established a Committee to recommend a “neutral, third-party permanent administrator” of the USF program.6Universal Service First Report and Order, ¶ 42. The Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC) was created as a subsidiary of the National Exchange Carrier Association (NECA). It is a private not-for-profit corporation.7See Changes to the Board of Directors of the National Exchange Carrier Association, Third Report and Order in CC Docket No. 97-21, Fourth Order on Reconsideration in CC Docket No. 97-21 and Eighth Order on Reconsideration in CC Docket No. 96-45, 13 FCC Rcd 25,058, 25,063–66, paras. 10–14 (1998); 47 C.F.R. § 54.701(a). The Commission appointed USAC the permanent Administrator of all of the federal universal service support mechanisms. See 47 C.F.R. §§ 54.702(b)–(m), 54.711, 54.715. USAC has a 19-member board of directors, which represent a variety of stakeholders in the USF system, both contributors and beneficiaries.8See 47 CFR § 54.703(b). The USAC board seats are broken down as follows: 1. three directors shall represent incumbent local exchange carriers; 2. two directors shall represent interexchange carriers; 3. one director shall represent commercial mobile radio service (CMRS)providers; 4. one director shall represent competitive local exchange carriers; 5. one director shall represent cable operators; 6. one director shall represent information service providers; 7. three directors shall represent schools that are eligible to receive discounts pursuant to E-rate; 8. one director shall represent libraries that are eligible to receive discounts pursuant to E-rate; 9. two directors shall represent rural health care providers that are eligible to receive supported services pursuant to the Tele-health program; 10. one director shall represent low-income consumers; 11. one director shall represent state telecommunications regulators; 12. one director shall represent state consumer advocates; and 13. the Chief Executive Officer of the Administrator. USAC submits nominations to the FCC chair, who approves the nominations.947 CFR § 54.703(c). See “Chairwoman Rosenworcel Names Seven Members to the Board of Directors of the Universal Service Administrative Company,” DA 21-1640 (Dec. 23, 2021), https://www.fcc.gov/document/chairwoman-names-seven-members-board-directors-usac.

USAC Has Massive Powers within the USF Construct

USAC’s Power to Set the Budget for the USF Programs

It would probably surprise people to find out that the budget for the four USF Programs is not set by the FCC, which Congress put in charge of the program, but rather by USAC, a private company. “For each quarter, the Administrator [of USAC] must submit its projections of demand for the federal universal service support mechanisms for high-cost areas, low-income consumers, schools and libraries, and rural health care providers, respectively, and the basis for those projections, to the Commission and the Office of the Managing Director at least sixty (60) calendar days prior to the start of that quarter.”1047 C.F.R. § 54.709(a)(3)

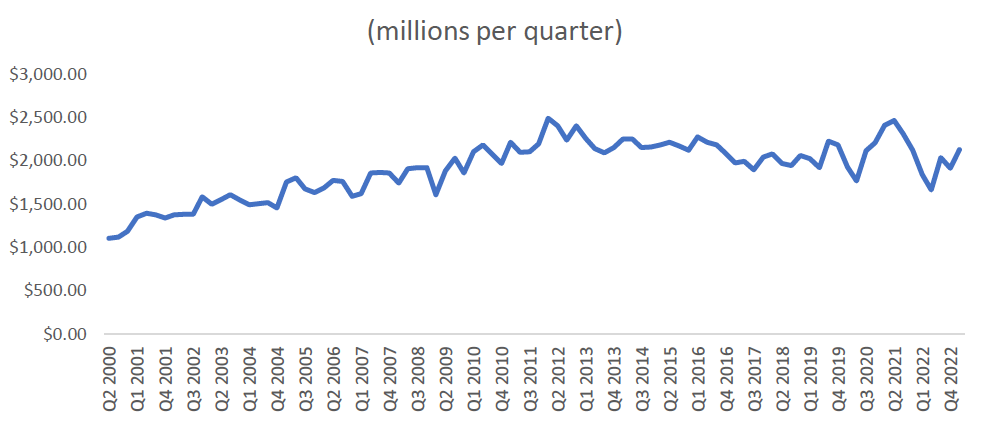

The total USF budget has roughly doubled since 2000, from just over a billion per quarter in 2000 to just over $2 billion per quarter in 2022 (figure 1).

Figure 1. USF Budget Per Quarter

Source: FCC, Contribution Factor & Quarterly Filings – Universal Service Fund (USF) Management Support, https://www.fcc.gov/general/contribution-factor-quarterly-filings-universal-service-fund-usf-management-support.

To put this into perspective, the entire FCC budget for overseeing all of its programs (everything from regulating radio and television to allocating and licensing spectrum) is just under $390 million, 20 times less than the budget administered by USAC. In this sense, USAC’s power, especially over broadband deployment and affordable access to broadband, dwarfs the power of the independent agency to which Congress delegated this power.

The FCC has tried vainly to impose some guardrails on the USF program, such as setting a “budget” for the Lifeline Program,11Lifeline and Link Up Reform and Modernization, Third Report and Order, 31 FCC Rcd 3692, WC Docket No. 11-42, ¶¶ 400–403 (2016). which Commissioner O’Reilly deemed “a joke, not a budget.”12B. Herold, FCC Adds Broadband to “Lifeline” Program in Party-Line Vote, Education Week (Mar. 31, 2016), https://www.edweek.org/technology/fcc-adds-broadband-to-lifeline-program-in-party-line-vote/2016/03. The General Accounting Office has long warned that subdelegating so much power to USAC could lead to massive waste, fraud, and abuse in the USF programs.13See, e.g., Greater Involvement Needed by FCC in the Management and Oversight of the E-rate Program, GAO-05-151, GAO (Feb. 9, 2005), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-05-151. See also, FCC Should Take Additional Action to Manage Fraud Risks in Its Program to Support Broadband Service in High-Cost Areas, GAO-20-27, GAO (Oct. 2019), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-27.pdf. Nonetheless, the FCC has all but abdicated its statutory responsibility to run one of the most critical programs to the American people.

USAC’s Power to Set the Contribution Factor

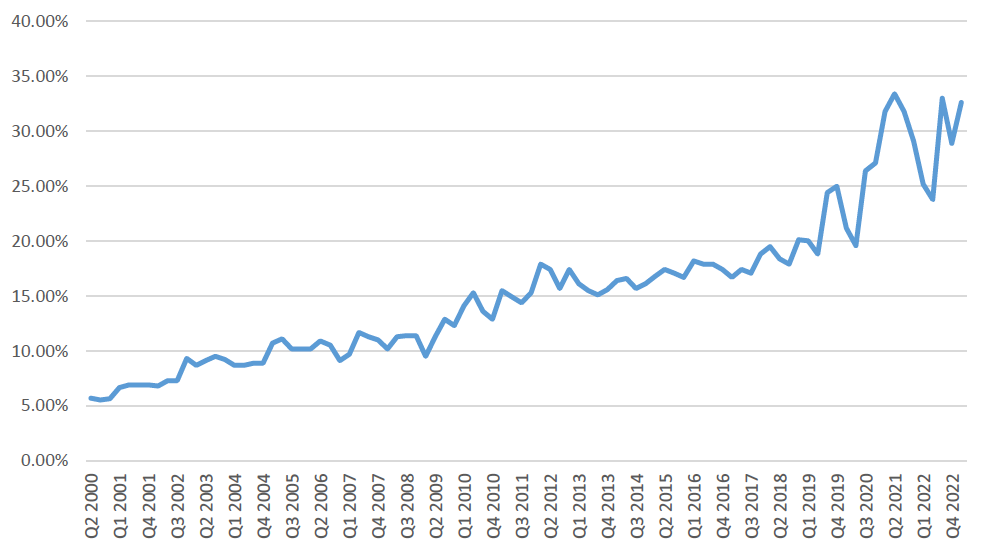

As noted in the introduction, USF programs are funded through fees (effectively taxes) assessed by carriers on telecommunications services.1447 U.S.C. § 254(d). USAC sets that contribution factor on a quarterly basis.15See, e.g., Proposed Fourth Quarter 2022 Universal Service Contribution Factor, DA 22-946 (Sept. 13, 2022), https://www.fcc.gov/document/4th-quarter-usf-contribution-factor-289-percent. The fee began at 5.7 percent in 2000,16Proposed Second Quarter 2000 Universal Service Case at 27, DA 00-517 (Mar. 7, 2000), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DA-00-517A1.pdf. but has grown rapidly in recent years, peaking at 33.4 percent in the second quarter of 2021 (figure 2).17Proposed Second Quarter 2021 Universal Service Contribution Factor, DA-21-308 (Mar. 12, 2021), https://www.fcc.gov/document/pn-announces-2q-usf-contribution-factor-334-percent.

Figure 2. USF Contribution Factor Increase, 2000–2022

Source: FCC, Contribution Factor & Quarterly Filings – Universal Service Fund (USF) Management Support, https://www.fcc.gov/general/contribution-factor-quarterly-filings-universal-service-fund-usf-management-support.

The FCC has virtually no input into the setting the quarterly contribution factor, and by regulation, those factors are “deemed approved by the Commission” if the FCC takes no action on USAC’s announcement of the next quarterly fee within fourteen days.18See 47 C.F.R. § 54.709(a)(3). The FCC has never objected to the nearly 100 quarterly announcements from USAC.

Providers of telecommunications services must file quarterly estimates with USAC (Form 499-Q) and make payments each quarter into the fund. In April of every year, providers must file a “true-up” Form 499-A, which USAC reviews. USAC has the power to investigate contributions and require providers to amend their filings and adjust their payments.19Glob. Crossing Telcomms. v. FCC, 605 F. App’x 4, 4 (D.C. Cir. 2015) (citing to Universal Serv. Contribution Methodology, Order, 27 FCC Rcd. 13,780, 13,782 (Nov. 5, 2012) where the FCC investigated Global Crossing for a fraudulent 499-A form and ordering Global Crossing to pay $5.6 million in additional USF contributions); Conference Grp., LLC v. FCC, 405 U.S. App. D.C. 420, 424, 720 F.3d 957, 961 (2013) (citing to In re Request for Review by InterCall, Inc. of Decision of Universal Service Administrator, 23 FCC Rcd. 10731 (2008) where the USAC investigated InterCall’s 499-A form to discover they were not properly categorizing themselves on the form by not including that they did audio tolling). Although USF fees are collected from providers, they are inevitably passed along to consumers, making them the most regressive tax in America, since the approximately 30 percent tax is paid by every American (except those that participate in the USF Lifeline Program).20See James Dunstan, The Arrival of the Federal Computer Commission, Regulatory Transparency Project (Aug. 27, 2021), https://regproject.org/blog/the-arrival-of-the-federal-computer-commission/.

USAC’s Power to Administer the Four USF Programs

To say that USAC “administers” the USF is a massive understatement. As a private entity, it is responsible for doling out over $8 billion a year to the four USF programs. It creates the Byzantine set of forms that participants must fill out, accepts or rejects these forms, administers deadlines strictly, and is empowered to conduct audits and recoup money after the fact if it determines that any of the FCC’s rules, in its opinion, have been violated. While USAC professes not to interpret FCC rules,21By-Laws of Universal Service Administrative Company, Art. II, Cl. 1, USAC (revised June 6, 2007), https://www.usac.org/wp-content/uploads/about/documents/leadership/usacbylaws.pdf (“Consistent with 47 C.F.R. 54.702(c), the Board will not make policy, interpret unclear provisions of the statute or rules, or interpret the intent of Congress, and will seek guidance from the Commission where the Act or rules are unclear.”). many of its decisions require substantial interpretation of highly complex rules, as discussed more fully in the quantitative study in Section IV.

Participants whose forms have been rejected may appeal back to USAC, though with little hope of USAC reversing itself. The same group within USAC that made the initial decision hears the appeal.22Appeals & Audits, USAC, https://www.usac.org/about/appeals-audits/appeals/ (last visited Sept. 30, 2022). The only way USAC will reverse itself is if the participant can show through clear evidence that USAC made an incorrect factual finding.23For example, if USAC denies funding based on a failure to timely file one of the essential forms, but a participant can demonstrate that the form was in fact timely filed, USAC will reverse itself. When the nearly inevitable denial occurs, participants must then take an appeal to the FCC.24Understanding FCC Processes, FCC, https://www.fcc.gov/general/understanding-fcc-processes (last visited Sept. 30, 2022). The Commission will undertake a de novo review, in which USAC does not participate. This means that the burden of proceeding and burden of proof on appeal are squarely on the participant, with those burdens never shifting to another party (because USAC is not a party in the appeal). Moreover, the Commission dispenses with such appeals through periodic (roughly monthly) omnibus orders,25See Universal Service, FCC, https://www.fcc.gov/general/universal-service (listing omnibus appeal orders for each month in 2022). lumping together dozens of appeals and ruling on them in large batches.26See, e.g., Streamlined Resolution of Requests Related to Actions by the Universal Service Administrative Company, DA 22-897 (Aug. 31, 2022) (dispensing with 129 separate appeals) (Streamlined Resolution of Requests). No separate analysis is conducted by the Commission, rather, the appeals are either granted or denied, with a single footnote to a string citation to past precedent for each category of appeal.27See id. at 2–3, n. 5 (ten E-rate appeals “dismissed on reconsideration” with a footnote dropped from the heading and citing a single prior precedent generally applicable to all ten appeals, and two additional case precedents for several of then appeals).

USAC’s Budget Is Paid for by Consumers and Program Participants

USAC’s internal budget for administering the USF comes right off the top. Its 2021 operating budget was $252 million,28See Universal Service Administrative Co., 2021 Annual Report at 6, https://www.usac.org/wp-content/uploads/about/documents/annual-reports/2021/2021_USAC_Annual_Report.pdf. or nearly two-thirds of the operating budget of the entire FCC. That means that approximately three percent of the entire USF budget goes to USAC’s overhead. Put another way, the average consumer pays approximately $1.00 per month to USAC to oversee the USF. USAC’s personnel budget alone is almost $100 million. As a private company, and a subsidiary of NECA, USAC doesn’t publish the salaries of its officers. Indeed, its “briefing books” only talk in terms of “salary increases.”29See, e.g., USAC Board of Directors Briefing Book at 16 (Apr. 28, 2020), https://www.usac.org/wp-content/uploads/about/documents/leadership/materials/bod/2020/2020-04-BOD-Briefing-Book-Public-Final.pdf (“RESOLVED, that the USAC Board of Directors, having reviewed the proposed 2020 merit-based salary increase for the USAC CEO, as recommended by the Executive Compensation Committee, hereby approves the salary increase, effective retroactively as of January 16, 2020.”). As a private entity, USAC isn’t subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) disclosures, rendering it all but impossible to determine the salaries or bonuses of USAC managers and staff.

In addition to skimming off the contribution base to cover its operating budget, it appears that the FCC has encouraged USAC to implement an “aggressive,” “incentive-based system for deterring improper payments,” including adopting an employee bonus structure that rewards efforts to recoup payments.30See Letter from Anthony J. Dale, Managing Director, FCC, to Brian Talbott, Chairman of the Board, USAC, dated (Dec. 1, 2008), https://transition.fcc.gov/omd/usac-letters/2008/120108-USAC-Internal-Control-Structure.pdf. In its 2019 Annual Report to the FCC,31Universal Service Administrative Co., 2019 Annual Report, https://www.usac.org/wp-content/uploads/about/documents/annual-reports/2019/USAC-2019-Annual-Report.pdf. USAC touted the $14.5 million it “recovered” through its Beneficiary and Contributor Audit Program (BCAP audits).32Id. at 6. It is interesting to note that the language used in USAC’s 2021 annual report was much softer concerning its role in recouping overpayments. See Universal Service Administrative Co., 2021 Annual Report, https://www.usac.org/wp-content/uploads/about/documents/annual-reports/2021/2021_USAC_Annual_Report.pdf (the only reference to recovering payments is in a footnote on page 5, stating support “does not include recoveries from audits, appeals, or other enforcement actions.”). Because of USAC’s opaqueness, it is not possible to determine how much, if any, of that recouped amount went directly into the pockets of USAC employees or management in the form of salary increases or bonuses. There nonetheless appear to be incentives for USAC employees to claw back as much money from participants as they can to support USAC’s operations, something that has a critical impact on the discussion below.

The Inherent Problem with Private Delegation

The way in which the FCC has chosen to structure the USF program is currently under fire in two pieces of litigation. Public interest groups have filed challenges to the ever-increasing contribution factors assessed by USAC in both the Fifth33See Consumers’ Research v. FCC, No 22-60008 (5th Cir. Jan. 5, 2022). and Sixths Circuits.34See Consumers’ Research v. FCC, No 21-3886 (6th Cir. Sept. 30, 2021). The plaintiffs in those cases argue that Congress cannot delegate revenue-raising power to the FCC.35See Brief of Petitioners, Consumers’ Research v. FCC, No 21-3886 (6th Cir. Sept. 30, 2021). That may well be the case.

We at TechFreedom filed amicus briefs in both cases arguing that regardless of whether the FCC can survive the “notoriously lax” “intelligible principle” exception to the non-delegation doctrine,36The “intelligible principle” states that so long as courts can find some direction in the statute that Congress gave agencies, delegating the implementation of that principle does not violate the nondelegation doctrine. See J.W. Hampton, Jr. & Co. v. United States, 276 U.S. 394 (1928). For a fuller discussion of the intelligible principle doctrine, see Amy Coney Barrett, Suspension and Delegation, 99 Cornell L. Rev. 251, 318 (2014). the further subdelegation, indeed, delegation to a private entity by the FCC, can’t survive a non-delegation challenge:

In any event, we know this much for sure: After Congress passed the USF’s enabling statute, the FCC botched the USF’s implementation. It was bad enough that Congress handed such broad and ill-defined regulatory power to an independent agency—a government entity not subject to direct control by democratically elected leadership. To make matters worse, though, the agency then passed the power again, handing it to a private organization, the Universal Service Administration Company (USAC). What’s more, it did so without Congress’s permission, which means that the USF is not subject to any congressionally established procedural guardrails.37TechFreedom, Amicus Brief for Consumers’ Research v. FCC at 3-4, No 22-60008 (5th Cir. Jan. 5, 2022), https://techfreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Filestamped-TechFreedom-Amicus-Brief-Consumers-Research-v.-FCC.pdf.

As this study will demonstrate, this private delegation, combined with a direct pecuniary incentive to recoup money from USF participants to line the coffers of a private company, is the worst delegation nightmare possible, and the type of private delegation that the Supreme Court warned of in Schechter Poultry.38A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935). In striking down the “Live Poultry Code” promulgated by the chicken dealers of New York and approved by President Franklin Roosevelt, the Supreme Court stated:

Would it be seriously contended that Congress could delegate its legislative authority to trade or industrial associations or groups so as to empower them to enact the laws they deem to be wise and beneficent for the rehabilitation and expansion of their trade or industries? Could trade or industrial associations or groups be constituted legislative bodies for that purpose because such associations or groups are familiar with the problems of their enterprises? And, could an effort of that sort be made valid by such a preface of generalities as to permissible aims as we find in section 1 [of the National Industrial Recovery Act].39Id. at 537.

“The answer,” the Court concluded, “is obvious. Such a delegation of legislative power is unknown to our law and is utterly inconsistent with the constitutional prerogatives and duties of Congress.”40Id.

A year after issuing Schechter Poultry, the Court confirmed the unconstitutionality of private delegation in Carter v. Carter Coal Co.41298 U.S. 238 (1936). That case was, in effect, the hypothetical in Schechter Poultry brought to life: The statute in question empowered coal industry groups to issue binding wage-and-hour codes. “This is legislative delegation in its most obnoxious form; for it is not even delegation to an official or an official body, presumptively disinterested, but to private persons whose interests may be and often are adverse to the interests of others in the same business.”42298 U.S. at 311. The Supreme Court in Carter went on to declare that private delegation is worse than intra-government delegation. “[I]n the very nature of things, one person may not be entrusted with the power to regulate the business of another.”43Id. Letting one private party regulate another, Carter insists, is “clearly arbitrary” and “an intolerable and unconstitutional interference with personal liberty and private property.”44Id. (citing, among other authorities, Schechter Poultry). As Carter shows, “[f]ederal lawmakers cannot delegate regulatory authority to a private entity.”45Ass’n of Am. R.R.s v. U.S. Dep’t of Trans., 721 F.3d 666, 670 (D.C. Cir. 2013), vacated and remanded, 575 U.S. 43 (2015). Under Carter, in fact, “even an intelligible principle cannot rescue a statute empowering private parties to wield regulatory authority.”46Id. at 671 (emphasis added).

Private Delegation Meets Unlimited Time for Claw Backs

In a country where not even treason can be prosecuted, after a lapse of three years, it could scarcely be supposed, that an individual would remain forever liable to a pecuniary forfeiture.47Adams v. Woods, 6 U.S. (2 Cranch) 336, 341, 2 L.Ed. 297 (1805) (Marshall, C.J.).

This quote, dating from 1805 by Chief Justice Marshall, should be axiomatic. Alas, it is not. As I discuss below, when it comes to money the government thinks it is owed, in many instances that debt lingers forever.

The FCC, USAC, and the Statute of Limitations

Commission Policy, 2004–2014

Private delegation plus incentives to claw back money to pay bonuses to staff is a horror story. That horror story has played out over time, as USAC, with acquiescence from the FCC, has modified its policies on repayment of USF funds it deems were improperly paid. Originally, the FCC directed USAC to complete its investigations and issue Commitment Adjustment Letters (CALs) within five years of the close of the funding year in question.48Schools and Libraries Universal Service Support Mechanism, CC Docket No. 02-6, Fifth Report and Order, 19 FCC Rcd 15808, (2004) (Fifth Report and Order).

We believe that some limitation on the timeframe for audits or other investigations is desirable in order to provide beneficiaries with certainty and closure in the E-rate applications and funding processes. For administrative efficiency, the time frame for such inquiry should match the record retention requirements and, similarly, should go into effect for Funding Year 2004. Accordingly, we announce our policy that we will initiate and complete any inquiries to determine whether or not statutory or rule violations exist within a five year period after final delivery of service for a specific funding year. We note that USAC and the Commission have several means of determining whether a violation has occurred, including reviewing the application, post application year auditing, invoice review and investigations. Under the policy we adopt today, USAC and the Commission shall carry out any audit or investigation that may lead to discovery of any violation of the statute or a rule within five years of the final delivery of service for a specific funding year.49Schools and Libraries Universal Service Support Mechanism, CC Docket No. 02-6, Fifth Report and Order, 19 FCC Rcd 15808, 15819-20 (2004) (Fifth Report and Order).

This period exceeds any of the statutes of limitations established elsewhere in the Communications Act or other applicable general statute of limitations.5047 U.S.C. § 503(b)(6)(A) (mandating that “no forfeiture penalty shall be determined or imposed against any person under this subsection if . . . more than 1 year prior to the date of issuance of the required notice or notice of apparent liability; or prior to the date of commencement of the current term of such license, whichever is earlier.”); 28 U.S.C. § 2462 (“enforcement of any civil fine, penalty, or forfeiture, pecuniary or otherwise, shall not be entertained unless commenced within five years from the date when the claim first accrued”). For example, telecommunications providers are subject to only a one-year statute of limitations when it comes to rate complaints.51See, e.g., BellSouth Telecommunications, LLC, FCC 16-98 (July 27, 2016) (Dissent of Commissioner Pai) (“Here’s the problem: We have issued this Notice of Apparent Liability (NAL) too late. The Communications Act imposes a one-year statute of limitations. Like most other statutes of limitations, it runs from when a violation is complete—in this case, when AT&T ‘charge[d]’ Dixie County and Orange County ‘a price above the lowest corresponding price.’ So even in the best-case scenario, the statute of limitations ran out 56 days ago, on June 1, 2016. That’s a shame because the Enforcement Bureau became aware of AT&T’s conduct two full years ago, just as the statute of limitations was beginning to run and long before it expired. That means we could have imposed a lawful forfeiture had we acted with alacrity (or even a modicum of urgency).”). But at least there was some limitation on USAC’s ability to reach back and try and recoup payments for alleged violations of the FCC’s rules, and the Commission acknowledged “the beneficiaries’ needs for certainty and closure in their E-rate application processes.”52Fifth Report and Order, ¶ 32. It also matched the document retention period for beneficiaries of the Schools and Libraries program of five years.53Id. at ¶ 47 (“We conclude that the adoption of a five-year record retention requirement will facilitate improved information collection during the auditing process and will enhance the ability of auditors to determine whether applicants and service providers have complied with program rules. Further, we believe that specific recordkeeping requirements not only prevent waste, fraud and abuse, but also protect applicants and/or service providers in the event of vendor disputes.” (footnote omitted)).

FCC Eliminates Any Notion of a Statute of Limitations

The FCC began to whittle away at this de facto statute of limitations in 2014 by extending the document retention period from five to ten years.54See Modernizing the E-rate Program for Schools and Libraries, WC Docket No. 13-184, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 29 FCC Rcd 8870, 8974–75, ¶ 262 (2014) (First Modernization Order) (extending the document retention period from five to ten years after the latter of the last day of the applicable funding year, or the service delivery deadline for the funding request); see also Requests for Review and/or Waiver of a Decision of the Universal Service Administrator by Eastchester UN Free School District, Eastchester, New York, et al., Order, DA 19-840, ¶ 3 (WCB 2019) (internal citations omitted) (“Until funding year (FY) 2015, applicants were required to retain all documents related to the application for, receipt, and delivery of discounted telecommunications and other supported services for at least five years after the last day of service delivered in a particulate funding year, and as of July 1, 2015, applicants must retain those documents for ten years.”).

We believe that proper documentation is crucial for demonstrating applicant and vendor compliance with E-rate rules, and for uncovering waste, fraud and abuse in the program, whether through compliance audits or investigations. Therefore, we revise our document retention requirements and compliance procedures and clarify that applicants must permit inspectors on their premises as described below.55First Modernization Order, ¶ 261.

Then, in 2017, the Commission essentially unshackled USAC when it declared that USAC no longer had to conclude its investigations and issue CALs or Commitment Adjustment Decision (COMAD) letters within five years of the end of the funding year in question.56Application for Review of a Decision of the Wireline Competition Bureau by Net56, Inc., Palatine, Illinois, CC Docket No. 02-6, Memorandum Opinion and Order, 32 FCC Rcd 963 (2017) (Net56 Order). In Net56, although USAC had concluded its initial investigation within five years, it had failed to issue the COMAD letter for the 2006 funding year until 2013 (six years after the close of the funding year).57USAC issued COMADs on April 10, 2013, for funding years 2006, 2007, and 2008. The Commission rejected Net56’s argument that the COMAD for 2006 was time-barred.

The Commission has a duty to make sure that the E-rate program is operated efficiently and effectively for the benefit of our nation’s schools and libraries. The Commission also has a duty to safeguard against waste, fraud, and abuse of the federal funds that go to support all of the universal service support mechanisms. The Debt Collection Improvement Act (DCIA) directs agencies to “try to collect a claim of the [U.S.] Government for money or property arising out of the activity of or referred to, the agency.” The Commission noted this requirement when adopting the five year policy, emphasizing that “our policy . . . does not affect the statutes of limitations applicable under the DCIA for collection of debts established by the Commission.” We will not construe the Commission’s administrative policy for completing inquiries expeditiously in a way that would impair the Commission’s ability to fulfill its statutory obligation to establish and collect its debts consistent with applicable statutes that do not impose similar time constraints on initiation of debt recovery actions.58Net56 Order, ¶ 10 (footnotes omitted).

Also in 2017, the Commission issued a letter demanding repayment from a telephone company receiving support under the USF High Cost program.

In 2008, the FCC’s OIG commenced an investigation into Blanca’s receipt of high-cost support beginning with 2004. In 2012, during the pendency of the OIG investigation, and pursuant to its data reconciliation policies, NECA conducted a review of Blanca’s 2011 Cost Study, and concluded that Blanca improperly included costs, loops, and revenues associated with providing CMRS, which is a non-regulated service, in its 2011 Cost Study.59Blanca Telephone Company Seeking Relief from the June 22, 2016 Letter Issued by the Office of the Managing Director Demanding Repayment of a Universal Service Fund Debt Pursuant to the Debt Collection Improvement Act, CC Docket No. 96-45, Memorandum Opinion and Order and Order on Reconsideration, 32 FCC Rcd 10594, 10611–12, ¶¶ 13, 44–45 (2017) (Blanca Order).

The Commission rejected Blanca’s claim that the recoupment was time-barred under the one-year statute of limitations applicable to forfeitures under Section 503 of the Communications Act.

In this case, we have chosen to use the collection tools made available under the DCIA and its implementing rules for the collection of debt. Blanca incorrectly argues that USF is not federal funding subject to the DCIA, and therefore, the agency lacks authority to initiate collection efforts, such as offset, to collect overpaid USF. As emphasized by the Commission in 2004, the DCIA’s definition of “debt” or “claim” was not “limited to funds that are owed to the Treasury,” but included all funds “‘owed the United States,’” including “overpayments from any agency-administered program.” When amending its debt collection rules to reflect the passage of the DCIA, the Commission made clear that it defined a “claim” to include debts arising from USF-related payments. Indeed, both the U.S. Supreme Court, and the United States Senate have characterized USF as a form of federal funding.60Id. at ¶ 51 (footnotes omitted).

The Commission defended this approach, contending that requiring Blanca to repay High Cost support that it mistakenly received would only return Blanca to the place it would have been had it not received the support in the first place.

Here, the Commission is merely seeking to recover sums improperly paid in which Blanca held no entitlement under section 254 and the Commission’s implementing rules. It is not a punitive measure that seeks to deter future misconduct by other carriers but merely returns Blanca to the status quo ante. It does not punish Blanca for the potential public and market harm arising from Blanca’s improper cost accounting but merely recovers for the USF a windfall to which Blanca was not entitled under the foregoing statutory and regulatory scheme. Any negative financial impact that Blanca may experience as a result of recovery of this improper payment cannot transform this action into a sanction or penalty.61Id. at ¶ 45 (footnotes omitted).

The Tenth Circuit affirmed the Commission in Blanca Telephone Company v. FCC, finding that the Commission’s actions were consistent with the DCIA.62Blanca Telephony Company v. FCC, 991 F.3d 1097 (10th Cir. 2021). “The DCIA authorizes agencies to collect debts owed to the United States and contains no limitations period preventing the FCC’s debt collection.”63Id. at 1110 (emphasis added).

The Legal Problem with a Lack of Statute of Limitations

Kokesh and Penalties

Whether an agency can recover money depends on whether such recovery constitutes a penalty. The Supreme Court made this clear in Kokesh v. SEC.64137 S. Ct. 1635 (2017). There, the court determined that “disgorgement” was a “penalty,” and therefore the five-year statute of limitations under 28 U.S.C. § 2462 should be applied. The Kokesh court distinguished disgorgement from restitution, which it defined as compensation “paid entirely to a private plaintiff.”65Id. at 1463. The question then becomes whether USAC’s (and the FCC’s) attempt to recoup USF support payments is a penalty, designed to “go beyond compensation, [is] intended to punish, and label defendants wrongdoers.”66Id. (quoting Gabelli v. SEC, 568 U.S. 44, 451–52 (2013)). The Commission disagreed, arguing that Kokesh did not apply to Blanca.

We in turn disagree that the Supreme Court’s Kokesh decision helps Blanca here. The Kokesh Court held that a Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) disgorgement action was a penalty for violating federal securities law, and thus, subject to the APA’s generally applicable five-year statute of limitations in section 2462 governing any “action, suit or proceeding for the enforcement of any civil fine, penalty, or forfeiture, pecuniary or otherwise.” Key to that decision was its finding that a penalty is designed to punish and deter future violations rather than to compensate a “victim.” The Court reasoned that SEC disgorgement was an action that left the defendant “worse off,” since a court could order disgorgement that “[exceeded] the profits gained as a result of the violation,” and that disregarded “a defendant’s expenses that reduced the amount of illegal profit.” The Court emphasized that when a sanction “can only be explained as . . . serving either retributive or deterrent purposes,” it is a “punishment.”67Blanca Order, ¶ 44 (footnotes omitted).

The Tenth Circuit agreed.

[W]e have previously concluded that just because a party violated a public law and because an agency wants to protect the public through a subsequent action does not necessarily make that action a penalty. See [United States v.] Telluride, 146 F.3d at 1246 (“[W]e see no reason to include all wrongs to the public as penalties.”). The Supreme Court’s decision in Kokesh did not change that. The identity of the wronged party is just one guiding principle when deciding whether government action is punitive. The fact that Blanca’s accounting violations wronged the public as opposed to a discrete private party does not decide the issue for us.

This finding is understandable within the context of the facts of the Blanca Order. Blanca would have provided the same service, regardless of whether it received the additional amount of High Cost support that it should not have received. The Commission did, in fact, return Blanca to the status quo ante. That approach might also be defensible within the context of the Net56 case. Although the Net56 Order is not clear, it appears that Net56 was the provider of broadband services under the E-rate program.68See Net56 Order, ¶ 1 (seeking recovery from Net56 for monies disbursed for provision of E-rate services to Country Club Hills School District 160).

The analysis of this approach, and certainly the equities, change dramatically in instances where USAC seeks recoupment from E-rate recipients themselves. The E-rate program was designed specifically to entice providers to offer their lowest rates to schools and libraries without broadband connections and to heavily subsidize those connections for students. USAC pays the “discounted portion” of the connection, up to 90 percent of the total cost. The beneficiary is responsible only for the non-discounted portion. Often the beneficiary could never afford to pay the full amount of the connection; but for the E-rate program, the school or library would go without a broadband connection. Recoupment does not return such schools to the status quo ante. Requiring those beneficiaries to pay back up to 90 percent of the cost of the connection to USAC for rule infractions acts as a direct penalty, in many cases potentially bankrupting the school or library.

The DCIA’s Total Lack of Guardrails

If USAC can seek recoupment of USF payments under the DCIA,6931 U.S.C. §§ 3711–17. then there exist no guardrails for USAC looking back into antiquity to find and profit from violations of the Commission’s rules. We have found virtually no cases where courts have put any limitations on how far back agencies can go to recover a “debt” to the United States under the DCIA. Indeed, regulations implementing the DCIA talk in terms of “aggressive agency collection.”

Each Federal agency shall take aggressive action, on a timely basis with effective followup, to collect all claims of the United States for money or property arising out of the activities of, or referred to, that agency in accordance with the standards set forth in this chapter.704 C.F.R. § 102.1(a).

Agencies are essentially on their own to determine what “on a timely basis” is.71See Grabis v. Office of Personnel Management, 424 F.3d 1265, 1269 (Fed. Cir. 2005). In A1 Diabetes & Med. Supply v. Azar, 937 F.3d 613, 621 (6th Cir. 2019), the Sixth Circuit remanded a case involving recoupment of overpaid Medicare payments but only because the court was unclear whether the DCIA applied or whether there was a separate statutory requirement as to timing (“It is not clear what kind of discretion and how much discretion the government has on timing. See, e.g., 42 C.F.R. § 401.607(c)(3); See also 42 U.S.C. § 1395ddd(f)(1)(A); 42 C.F.R. § 405.379(h)(2). And it is not clear whether, if the government is statutorily obligated to collect recoupment and if it must do so within a certain time, it may delay the bulk of the recoupment payments until after the ALJ hearing and decision, keeping in mind that the delays stem from bureaucratic snags in the government’s appeal process.”). Is “timely” five years? Ten years? Forever? Apparently, that decision is completely at the discretion of the agency. And, in this instance, given that the FCC has privately delegated enforcement powers to USAC, a private company is allowed to decide how far back it can reach to demand repayment of a “government” debt.

An Empirical Study of USAC’s Practices Since Net56

Given that USAC has a direct pecuniary interest in seeing money returned to the USF to cover its own operations (and quite probably allow for paying increased salaries and/or bonuses to staff members), the question becomes, what was USAC’s reaction to Net56 and Blanca? Has USAC reached further back in time to attempt to recoup monies paid out through the USF? There has been some anecdotal evidence of this.72See Consolidated Request for Review, Robeson County, CC Docket 02-06 (Apr. 24, 2018) (2007–2009 funding years, COMAD issued 2018); Request for Review, Granville County Public Schools, CC Docket 02-06 (Apr. 24, 2018) (2004, 2007, 2008 funding years, COMAD issued 2018); Consolidated Request for Review, Robeson County Public Schools, CC Docket 02-06 (Apr. 24, 2018) (2002 funding year, COMAD issued 2018); Request for Review, Wilson County School District, CC Docket 02-06 (July 29, 2020); Request for Review and Waiver, Navajo Nation Library Consortium, CC Docket 02-06 (July 29, 2020) (2003 funding year, COMAD issued 2020). The undersigned author is counsel of record on the Navajo Nation appeal.

The remainder of this paper consists of an empirical analysis of the proposition that, indeed, USAC has gone back to its files to issue COMADs to try and recoup funds well beyond the five-year “policy” deadline, beginning after Net56.

Structure of the Study

I have chosen to focus on appeals in the E-rate program because of the unfair impacts discussed above in Section III.B.1.73As will become apparent almost immediately, while extending the analysis to the other three programs would provide a fuller picture, the sheer number of E-rate appeals is so large that such an expansion is beyond the capabilities of this study. In the future, it would be helpful if such an analysis was undertaken of appeals in the other three major USF programs. Those appeals are filed in FCC Docket 02-06. As of June 2022, when this study began, there were 3,875 appeals filed in the docket. Because of this large number, I have limited my analysis to appeals filed from December 2015 through the second quarter of 2022. That number is approximately 1,850. There are many bases for appeal. I have eliminated from full analysis those appeals that are ministerial in nature and did not require USAC to reach conclusions as to whether the FCC’s substantive rules were violated. Excluded appeals include:74See Streamlined Resolution of Requests, supra n. 27 (dispensing with 129 separate appeals in 19 different categories).

- late-filed USAC forms;

- late-filed appeals;

- ministerial and/or clerical errors in forms;

- services delivered outside funding year window;

- cases involving filing extensions following the FCC’s “Jefferson-Madison” decision; and

- construction not completed during funding year.

I also excluded appeals where the documents submitted in the docket could not be analyzed due to insufficient information (e.g., it was not possible to determine either the funding year or the USAC decision date), corrupted documents, or in a few cases, it simply was not possible to determine the basis of the appeal. I also only searched the FCC ECFS database for “Appeals,” meaning that if an appeal was filed, but mislabeled by the appellant, that appeal has been excluded from the analysis. This left 321 appeals filed after USAC findings of substantive violations of FCC rules, including:

- competitive bidding violations (including failure to use cost as primary factor in awarding contracts);

- failure to wait the required 28 days prior to awarding a contract;

- no signed contract;

- services found not to be cost-effective;

- improper discount calculations or failure to pay non-discounted portion;

- duplicative services;

- non-supported services or equipment;

- invalid beneficiary;

- violation of the FCC’s “red-light” rule;75The FCC red-light rule states that beneficiaries cannot receive USF support if there is a pending order requiring them to pay back the government any owed funds. and

- failure to adequately respond to USAC investigations.

I then compared the funding year involved with the date of the USAC decision (either a CAL or a COMAD) and calculated the total number of months between the end of the funding year and issuance of the USAC decision. For decisions issued within the funding year, I assigned a value of “0.”

Results of the Study

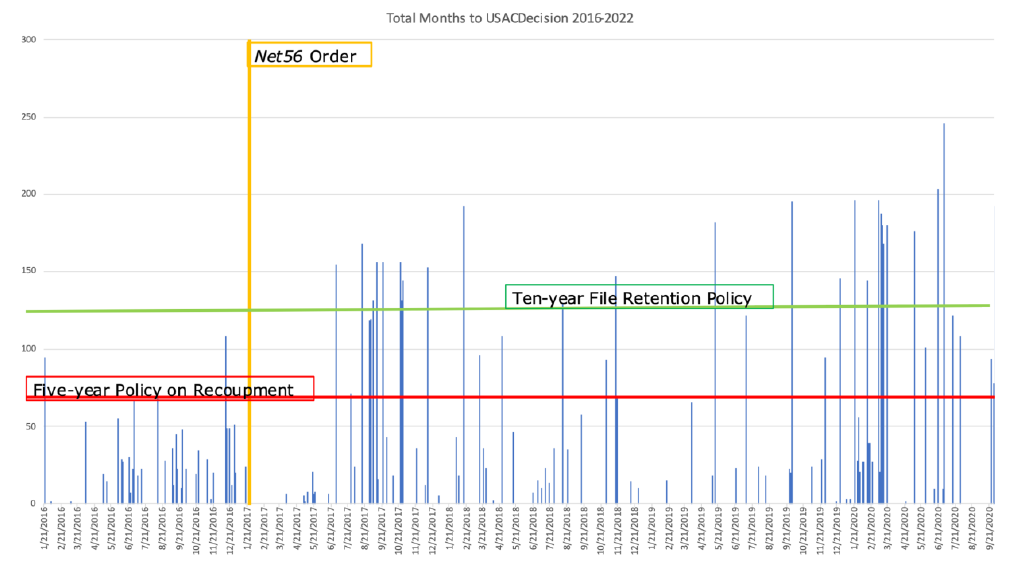

As suspected, a few months after the FCC abandoned its five-year de facto statute of limitations in January 2017, USAC began issuing COMADs for periods dating back substantially beyond five years. Figure 3 depicts all substantive decisions between December, 2015 and June, 2022.

Figure 3. Total Months from End of Funding Year to USAC Decision (2016–2022)

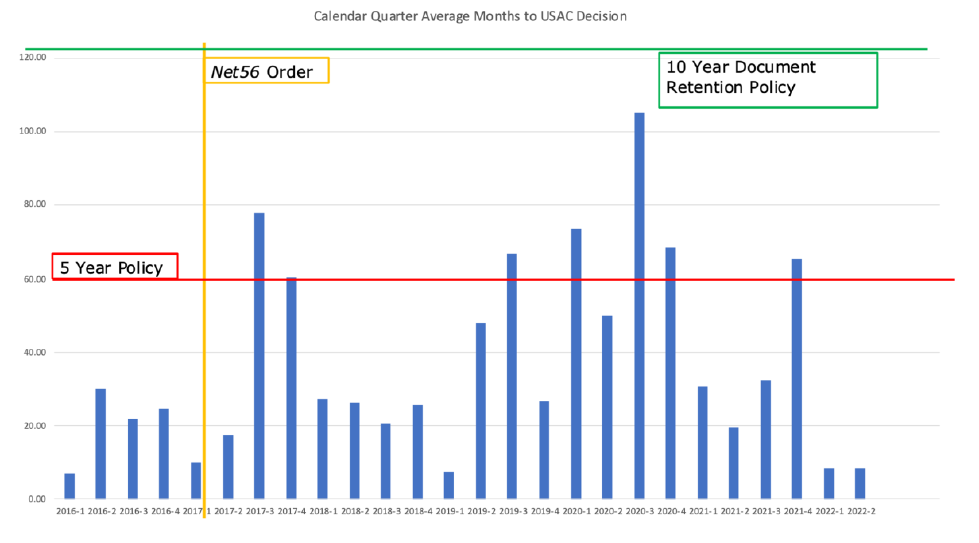

An analysis of the quarterly average time (in months) from the end of a funding year to a USAC decision renders an even starker picture of USAC’s actions, in figure 4.

Figure 4. Average Months to USAC Decision by Calendar Quarter (2016–2022)

Note the huge spike in the third and fourth quarters of 2017, where the average time from the end of the funding year to the issuance of a USAC decision increased from 13.71 months in the first half of 2017 to 77.92 months (6.5 years) in the third quarter of 2017. This includes appeals of ten decisions issued more than ten years after the end of the funding year (and thus beyond even the document retention period set by the FCC in 2014).76See Request for DRAW Academy, CC Docket 02-06 (Aug. 15, 2017) (2002 funding year, COMAD issued 2017); Request for Review, San Bernardino City Unified School District, CC Docket 02-06 (Aug. 29, 2017) (2006 funding year, COMAD issued 2017); Request for Review, Spokane Pubic Schools, CC Docket 02-06 (Aug. 31, 2017) (2006 funding year, COMAD issued 2017); Request for Review, Freshwater Education District, CC Docket 02-06 (Sept. 5, 2017) (2005 funding year, COMAD issued 2017); Request for Review, White Pine Library, CC Docket 02-06 (Sept. 12, 2017) (2003 funding year, COMAD issued 2017); Request for Review, Crystal Automation Services, Inc., CC Docket 02-06 (Sept. 22, 2017) (2003 funding year, COMAD issued 2017); Request for Review, Clare-Gladwin Regional Education Service District, CC Docket 02-06 (Oct. 23, 2017) (2003 funding year, COMAD issued 2017); Request for Review, Twin Rivers Unified School District, CC Docket 02-06 (Oct. 26, 2017) (2005 funding year, COMAD issued 2017); Request for Review, Ithaca Public School District, CC Docket 02-06 (Oct. 27, 2017) (2004 funding year, COMAD issued 2017); Request for Review, Portales Municipal Schools, CC Docket 02-06 (Dec. 12, 2017) (2004 funding year, COMAD issued 2017).

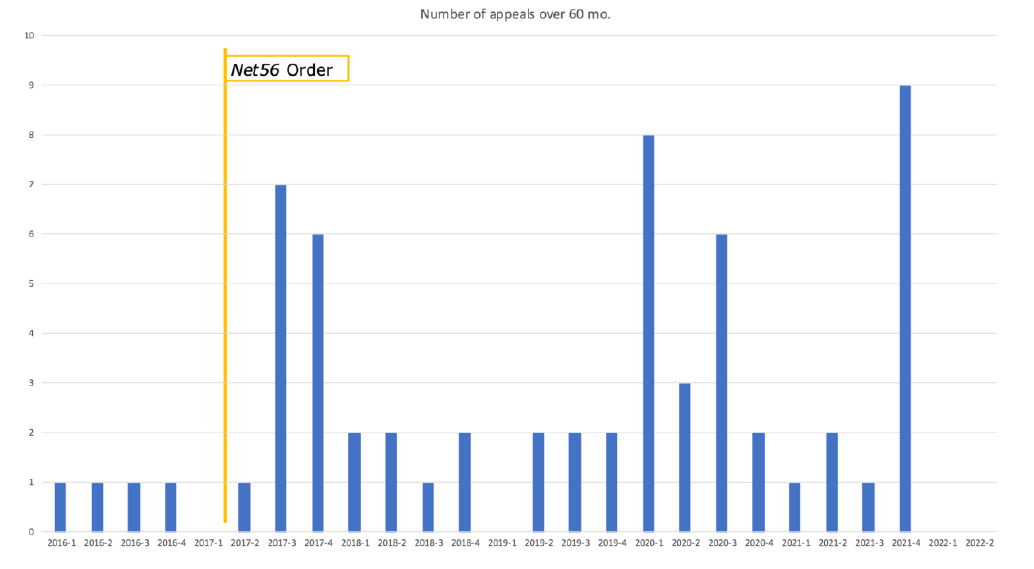

Figure 5 below shows the total number of appeals, per calendar quarter, from 2016 through the second quarter of 2022 which were based on USAC decisions rendered beyond 60 months after the end of the funding year.

Figure 5. Number of Appeals Where Decision Rendered Beyond 60 Month by Calendar Quarter (2016–2022)

Here again, we see that prior to the Net56 Order, there were few appeals involving USAC decisions beyond the five-year policy.77Indeed, the Net56 appeal is one of the four appeals depicted to the left of the yellow line in figure 5. Once USAC had the blessing of the FCC to begin reaching back beyond five years, within a few months, it consistently began pumping out COMADs reaching back far beyond the old five-year policy. Do note that there have been no appeals in the first half of 2022 beyond the five-year policy period. Perhaps USAC is becoming aware of the scrutiny it may be coming under?78Many of the “zombie” appeals—those over five years, have been submitted by experienced telecommunications lawyers who have made very strong arguments concerning the inequities of USAC’s actions reaching so far back in time.

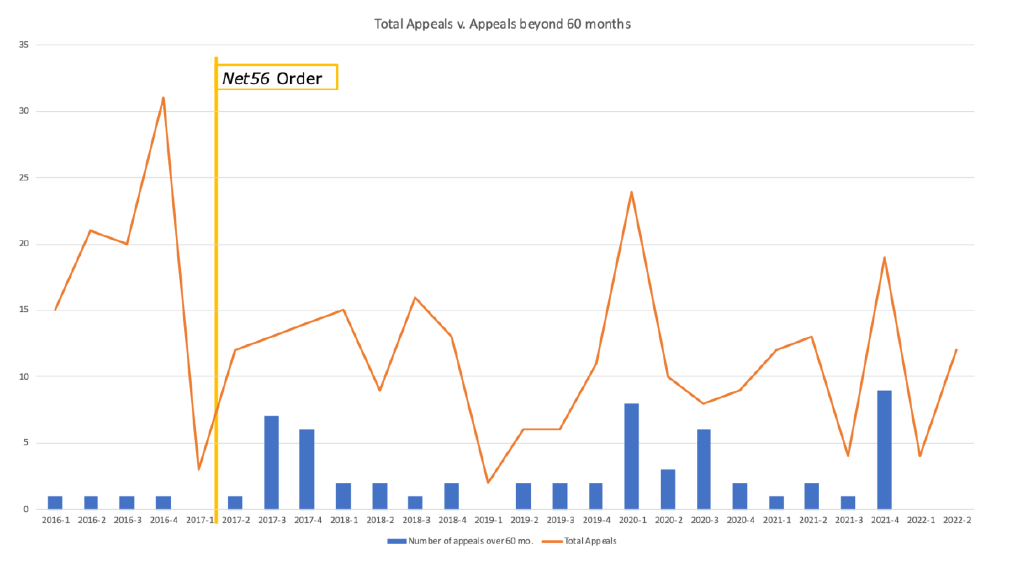

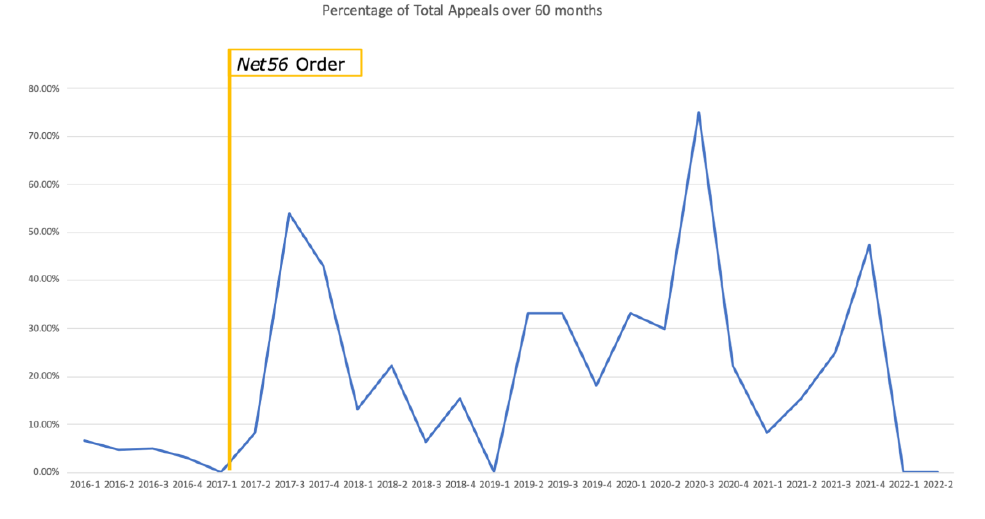

Figures 6 and 7 show that a considerable amount of USAC’s energy post–Net 56 Order has been spent pursuing recoupment of USF funding beyond five years.

Figure 6. Comparison of Total Appeals vs. Appeals beyond 60 Month by Calendar Quarter (2016–2022)

Figure 7. Percentage of Total Appeals Over 60 Months by Calendar Quarter (2016–2022)

Prior to the Net56 Order, very few USAC decisions came outside of the five-year policy window. Post-Net56, however, USAC devoted many more resources to old cases, including 75 percent of the decisions it rendered in the third quarter of 2020.

Moreover, recall that these appeals are not over ministerial or clerical mistakes, or missed deadlines, issues that lend themselves to simple submissions of factual evidence on appeal. These appeals have to do with highly fact-specific questions of rule violations. Indeed, in the eight cases listed above where decisions came down after ten years of delay, almost all of them centered around the issue of whether the beneficiary properly conducted the competitive bidding process or whether the ultimate recipient of the contract unduly participated in the preparation of the required forms.

It should be of little surprise, therefore, that as far as we can find, none of the appeals involving time frames over eight years have been decided since Net56. It’s almost as if the FCC recognizes the monster it has created in USAC and doesn’t know what to do with these cases.79Indeed, in my private practice, I have several appeals in E-rate cases (not involving the statute of limitations issue) that have been pending at the FCC for over thirteen years.

Implications of This Study

The implications of this study should send shivers down the spine of anyone interested in good governance. It’s bad enough that a government agency is untethered from any notion of timeliness in collecting its debts. It’s even worse when it transfers its ability to procrastinate to a private entity. While delegation to the Executive Branch harms “principles of political accountability,” such “harm is doubled . . . in the context of a transfer of authority . . . to private individuals.”80NARUC v. FCC, 737 F.2d 1095, 1143 n.41 (D.C. Cir. 1984).

Harm to the USF and Its Participants

Further harms may be less intuitive, but they are no less real; some of them are analyzed in this section.

Longer Time Frames for USAC Decisions Makes Appeals More Difficult

The current system of enforcing FCC rules related to the USF is already upside down. USAC investigates rule violations and then issues either a CAL or COMAD based on its findings that participants in the program can then appeal to the FCC. The problem is that USAC is not a participant in that appeal, meaning that appellants must refute the findings made by USAC on a “cold” record. There is no chance to directly challenge USAC’s methodology, gain discovery on USAC, or take any of the normal litigation steps we, as lawyers, are used to.81Moreover, as referenced above, as a private entity, USAC is not subject to FOIA requests. This process effectively shifts the burden of proceeding and burden of proof to the appellant (a guilty-until-proven-innocent model). If USAC issues a timely decision (i.e., within five years of the end of the funding year), then mustering the necessary documents and other proof is not overly burdensome on appellants. Stretch the USAC decision out past five years, or worse, past the ten-year document retention period, and the chance that an appellant can put together a persuasive case dwindles. People move on, responsibility for E-rate compliance may change offices, and files are inevitably lost. Given that most of the “delayed” cases involve issues of whether the competitive bidding rules were followed, or whether the winning bidder was chosen using price as the “dominant factor,” or whether the ultimate contract awardee imparted undue influence on the process, one can imagine the near impossibility of an appellant proving its case after a decade of not even knowing that there might be allegations of rule violations.

With Endless Potential Liability, Potential Participants Are Scared Away from Programs Like E-rate

At a recent “listening session”82The FCC calls meetings with tribal leaders “listening sessions” if they do not rise to the rule requirements of “formal consultation.” See Native Nations Communications Task Force, Recommendations for Improving Required Tribal Engagement Between Covered Providers and Tribal Governments, FCC (adopted Dec. 30, 2020), https://www.fcc.gov/sites/default/files/nnctf_tribal_engagement_report_12.30.20.pdf. for tribal leaders, the FCC asked why participation by Native American Tribes in the E-rate program was so low. A number of reasons were suggested, including lack of knowledge of the availability of E-rate funding in Indian Country, as well as the complexity of the rules. I suggested that the lack of closure on funding year recoupments, coupled with the amounts involved (because of the 90 percent discount rate available to most tribes) was a major barrier, in that many tribes are unwilling to participate in a program that must be “booked” as a contingent liability, presumably forever. The representative from USAC’s response was classic, effectively saying that so long as tribes comply with all the rules and all the filing deadlines, they have nothing to worry about. Since a participant can never know the final answer to that until they receive a COMAD, that’s cold comfort, and it has kept many needy parties out of the program, for fear of crushing reparations they might have to pay.

With Eternal Contingent Liability, Many Participants Are Forced to Hire Expensive Consultants

One way many participants minimize their risk of noncompliance with the FCC’s rules, and possible recoupment of funds, is to hire expensive consultants to assist them in the process. These consultants will assist in filling out the USAC forms, conducting the bidding process, and interfacing with USAC personnel. They can also serve the vital function of recordkeeping. Where do these consultants come from? In true Washington, DC revolving-door form, they are predominantly ex-FCC and ex-USAC staffers, who know the law, and more importantly, “the lore” of how things work (and whom to call at USAC to smooth things over). The biggest problem with this is that FCC rules explicitly prohibit rolling the costs of such consultants into the USF funding, meaning that participants must separately come up with the funding to pay the consultancy fees. For smaller participants with smaller funding requirements, these fees become exorbitant and drive worthy beneficiaries out of the program altogether.

Harms to Overall Good Governance

For those close to the USF, the intolerable nature of the current environment is obvious. But why should the larger body politic care about a program, that while large at $8 billion a year, might not impact them directly (but for the fact that they’re paying a hugely regressive tax on their cellphone bills)? The answer to that is twofold.

First, other agencies may follow the FCC’s lead. Rather than abide by statutes of limitations set forth in their governing statutes to claw back benefits they have paid out, they may choose to characterize those benefits as “debts to the government,” subject to the DCIA, and therefore time has no meaning, and debts may continue forever. As the percentage of government spending to GDP has risen from 11 percent in 1950 to 32 percent in 2020,83 See US Government Spending History from 1900, US Government Spending, https://www.usgovernmentspending.com/past_spending#:~:text=Government%20spending%20in%20the%20United,to%20almost%2040%20percent%20today.&text=Government%20Spending%20started%20out%20at,Gross%20Domestic%20Product%20(GDP) (last visited Sept. 30, 2022). government benefits as a percentage of GDP have tripled. This means more and more payments made by the government might be deemed debts to the government and potentially subject to recoupment forever.

Even more chilling is the thought that the government can enlist private entities as bounty hunters to go after those debts, giving them a cut of the take in returning money to the government. Instead of 87,000 new IRS agents authorized under the inaptly named “Inflation Reduction Act,” who at least are government civil servants (and presumably only receiving their GS-grade salaries), think instead of the IRS (or any other agency), employing marching armies of collection agents, under the color of law, to recoup debts from American citizens, unfettered by pesky statutes of limitations.84See M. Cosgel and T. Miceli, Tax Collection in History, Univ. Conn. Econ. Working Papers, (Dec. 2007), https://opencommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1196&context=econ_wpapers (“Tax collectors were not always government officials. They were sometimes private individuals who collected taxes on behalf of the government under an agency relationship.”).

What Should the FCC Do about the Situation?

The FCC must realize that it has a problem. As mentioned above, it appears that none of the appeals with “shelf lives” of more than ten years has been decided. They’re just sitting there. That’s good news for the appellants, as most, if not all, haven’t paid back any of the funds USAC is seeking to recoup while the appeals gather dust at the FCC. Yet these appellants still know that they could be on the hook to repay that money, in some instances millions of dollars. Some of those appellants have exited the program, and especially for the E-rate program, that means that there are many children who have limited or no access to broadband in their schools and libraries, the direct opposite result from what the program intended.

First, the Commission should dismiss any pending appeal that is based on a USAC ruling that came out beyond the paperwork retention period in question (be it five or ten years, which was applicable at the time of funding year). The FCC can equitably conclude that it should not be looking to recover a “government debt” from recipients beyond the time period in which it instructed them to retain all paperwork.

Second, the Commission should remand all remaining cases decided beyond five years to USAC and require USAC to demonstrate why it was unable to issue those decisions within the five-year policy period. There may be some instances where USAC can demonstrate that recipients hindered their timely investigations through misrepresentation or a refusal to cooperate. In those instances, USAC should reissue its decision demonstrating the basis and then participate in a future appeal at the FCC as an active party. The remainder of those cases should be dismissed.

Third, the Commission should modify its rules and policies to reinstate the five-year policy but allow USAC to issue orders beyond that date in the event it can demonstrate why actions of the recipients caused the delay. In those cases, USAC should be required to participate in the appeals process as a party.

Fourth, the Commission should change its rules to direct that no money recouped by USAC can be used to pay salaries or bonuses to employees, to eliminate the perverse incentive of USAC to try and reach back as far as possible with its investigations in order to line its own pockets. All moneys recouped should instead be applied to the programs themselves (and not USAC’s operational budget) in hopes of delaying the death spiral of the overall program because the contribution factor continues to rise.

Fifth, the Commission needs to modify its rules to rein in USAC’s power. The FCC, and not USAC, should set the USF budget every year. The FCC, and not USAC, should set the contribution factor and be required to vote on it each quarter as a measure of accountability.85As noted above, USAC merely submits these figures to the FCC, and they are “deemed granted” unless the FCC objects, which it has never done. Let the FCC Commissioners explain, on the record, every quarter, why American consumers are paying a 30 percent tax on their phone bills and where exactly that money is going.

Finally, Congress needs to step in and pass legislation. The USF program needs a complete overhaul. Congress should prohibit the private delegation to USAC that the FCC has done, effectively abdicating its role as a regulator and removing virtually all of the transparency from the program. Congress also needs to put the program on firm financial footing by removing the contribution mechanism and replacing it with a budgeted appropriation to operate the program.

Conclusion

The FCC is right to fight against waste, fraud, and abuse within the USF. The way in which it has chosen to do so, however, by delegating that authority to a private entity, is a clear violation of Article I of the Constitution. To allow USAC to recoup monies paid to beneficiaries outside of any form of statute of limitations, and to keep that money for its own uses (including paying salaries and bonuses), should be an afront to any partisan of good government. This study proves once again the adage “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority; still more when you superadd the tendency of the certainty of corruption by authority.”86Letter from Lord Acton to Mandell Creighton (Apr. 5, 1887).

I have no illusions that this study will somehow cause the scales to fall from the eyes of those who might effect change within the USF system. The FCC has demonstrated that it has no stomach for actually administering the program, and USAC itself is headed up by stakeholders in the ecosystem, who have far more to gain by a continuation of the private delegation than from converting to a more constitutional regulatory scheme. If future time and resources allow, I’d like to extend this study to the other three USF programs (High Cost, Lifeline, and Tele-health) to see if similar results can be gleaned from that data.

My condolences and best wishes go out to those beneficiaries who have been caught in USAC’s timeless net. I can only hope that the FCC will grant the appeals of those who have been blindsided by USAC after decades of thinking they were doing the right thing.