Introduction

Undocumented immigrants are nonresident aliens who do not have the right to work and receive income in the United States. According to an estimation by Warren (2020), the total US undocumented population was about 10.6 million in 2018, which is larger than most state populations.1According to the 2020 census, only 10 states have a population that exceeds 10 million. Undocumented immigrants contribute significantly to the US economy but have yet to be fully integrated into US society: they are not eligible for a driver license in many states; not eligible for unemployment and pension benefits; less likely to be covered by health insurance; more likely to take up low-wage jobs.

For professional employment, occupational licensing has been a huge barrier for undocumented immigrants to access high-wage jobs. Licensing regulations in the US affects more than one-fourth of workers and limits job opportunities (Blair and Chung, 2019; Kleiner, 2000; Kleiner and Krueger, 2013; Plemmons, 2023). The regulations require workers to obtain certain qualification (through formal education, training, or examinations) in order to be a licensed practitioners and work legally in a profession. But, plenty of professional licenses also require a legal work status, which many undocumented immigrants do not have. From this perspective, the restrictions from these regulations limit the economy from fully using preexisting human resources.

This paper documents the benefits of lifting occupational license restrictions on undocumented immigrants, leveraging a 2014 policy change in California (CA law). The legislation mandated that licensing boards under the California Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA) cannot deny a license application based on one’s citizenship or immigration status for dozens of licensed professions. While previous efforts in other states granted license access to undocumented immigrants, the California policy impacted a far bigger undocumented community. Using a generalized difference-in-differences (DID) approach that analyzes likely undocumented immigrants in the American Community Survey (ACS), I compare the undocumented population’s employment status in California with that in other states before and after the policy change.2I also find similar patterns using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) as a robustness check. I find that the policy increased the employment of undocumented workers by about 1 percentage point on average. The result is robust when applying entropy balancing (EB)—a recent variant of matching—to correct the imbalance in observables (Hainmueller, 2012). In addition to policy endogeneity, another challenge is to separate the policy effect from the driver’s license reform, which has an overlapping implementation schedule in California. (Amuedo-Dorantes et al., 2020) find that granting undocumented immigrants access to a driver license in a dozen of states (including CA) promoted their employment, particularly in the transportation industry. My result shows a significantly stronger impact on “covered” licensed professions but not on transportation-related occupations. These results provide evidence that the DID estimate captures a different effect than the driver’s license reform.

I also find stronger impacts on lower-education and blue-collar licensed professions and for older and Hispanic workers. To the extent that unnecessary licensing requirements—that residency status does not predict skill levels—created excessive barriers against undocumented workers, the policy successfully helped a subset of the population. At the same time, the null effect found here in higher-education licensed professions remains an impediment for the US economy to fully use preexisting human capital.

In addition to focusing on undocumented immigrants, I investigate the general equilibrium effect and find suggestive evidence that the CA law is not a zero-sum policy. While the increased employment of undocumented workers did not crowd out documented immigrants or US-born workers, the law drew unemployed individuals into licensed professions. Taken together, while the previous legal work status requirement restricted labor supply and created shortages, lifting it fulfilled the unmet demands instead of displacing existing job opportunities.

This paper is among the first to quantify the benefits of lifting license restrictions on undocumented immigrants in the US. The closest attempt is by Grelewicz (2020), who also investigates the same legislation and finds that the policy change increased the license attainment and earnings of undocumented immigrants.3Lara (2014) also provides an executive summary of this policy. I complement his findings by examining employment statuses and uncovering subgroup differences. Since hostile environments in various aspects of life have adversely impacted immigrants, overturning the restrictive policy has greatly improved their welfare (Areans Arroyo and Schmidpeter, 2022; Cho, 2022; Churchill et al., 2023; Rubalcaba et al., 2023).

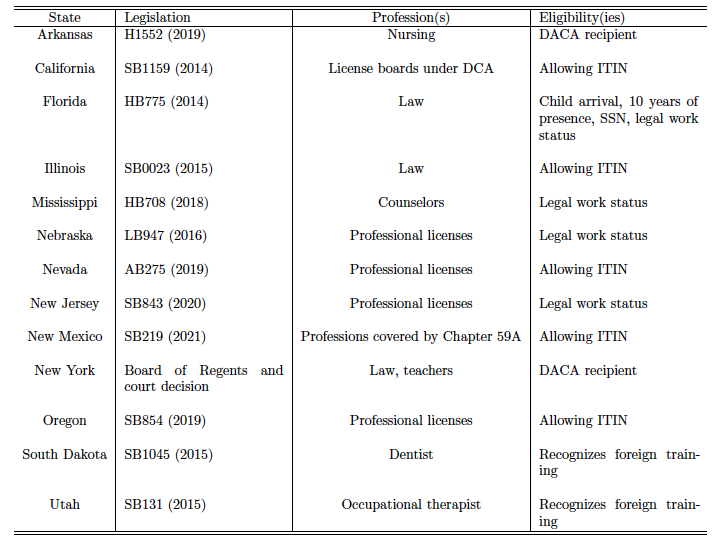

My results also support similar initiatives in a number of states that grant license access to undocumented immigrants. However, the impacts of many of them were limited by the scope of the policy.4In appendix table A1, I summarize similar policies in other states. Regulators in those states could better use the readily available labor supply and human capital by removing unnecessary requirements that barely predict skill levels.

Overall, my findings speak to the distributional effects of occupational licensing by highlighting the importance of removing labor market barriers that limit marginalized populations from accessing employment. Studies have found that licensing disproportionately affects minority and female workers (Blair and Chung, 2021, 2022; Chung and Zou, 2021; Law and Marks, 2009; Sheehan and Thomas, 2023; Xia, 2021). A few have studied licensing impacts on immigrants, including wage premiums (Cassidy and Dacass, 2021; Gomez et al., 2015; Tani, 2020) and employment (Federman et al., 2006; Peterson et al., 2014; Brucker et al., 2021).

Policy Background

In late 80s and early 90s, American sentiment against undocumented immigrants rose, giving rise to several restrictive policies (Alvarez and Butterfield, 2000; Citrin et al., 1997). At the federal level, the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act limited illegal immigrants’ access to jobs. At the state level, a notable initiative, Proposition 187, was created in 1994 in California, which created a hostile environment against illegal immigrants, including restrictions on their access to basic healthcare and public education.

Since then, the undocumented population in the US has continued to face a difficult environment in the labor market. Despite being aware that undocumented immigrants have no legal rights to work, some US employers have exploited their weakened bargaining power to save labor costs, including salary and fringe benefits (Massey and Gentsch, 2014). Also, due to demographic changes after the baby boom in the 70s, undocumented workers have become a source to fill the demand for entry-level and low-skilled positions (Passel, 1986).

After a century-long debate, states including California started to integrate undocumented immigrants into US society (Olivas, 2017), which included increasing occupational license access in the 2010s.5Examples of earlier federal reforms that offer access to work and higher education for immigrants include the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Coupled with several initiatives, granting undocumented immigrants this access has been one big step forward in creating a more welcoming labor market.6An important symbolic legislation is SB 396, which removed most of the restrictions mandated by Proposition 187. I provide a summary in the technical appendix of the covered professions and immigrant population of each legislation.

Senate bill 1159 was passed on September 2014 to prohibit licensing boards under the California DCA from denying licensure to an applicant based on their citizenship or immigration status (“CA law” hereafter), and the boards were required to implement the changes in 2015. The initiative stands out among earlier attempts for two reasons. First, the bill targeted individuals beyond DACA receipts and individuals with work authorization as it allowed people to use Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs) to prove their identity, welcoming undocumented immigrants.7Undocumented immigrants are not eligible for Social Security numbers (SSNs), which are used to prove one’s identity for most occupational licenses. Immigrants under the DACA or with temporary protected status in principle were eligible for a license as long as they had an SSN. Second, the bill applied to dozens of license boards under the DCA that potentially benefited a bigger undocumented population than similar concurrent initiatives in other states.

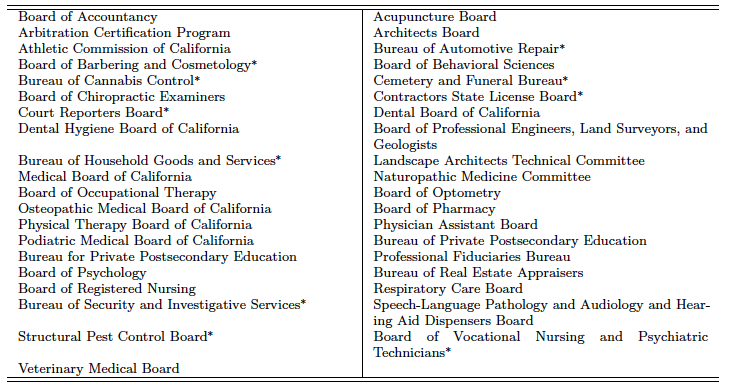

Appendix table A2 lists 39 license boards that are supervised by the DCA. Except for a few with an asterisk (such as barbering and cosmology), most of the covered professions require an undergraduate degree. I later use these different education requirements to explore the CA law’s heterogeneous effects.

Methodology

I start by analyzing data from the ACS, which contains rich information on demographic and employment information of a nationally representative sample of US workers each year, from 2009 to 2019.8The data are pooled from IPUMS USA (Ruggles et al., 2022).[\mfn] The main difficulty is identifying undocumented immigrants since no particular questions in the survey collect information on legal status. To overcome this and define likely undocumented immigrants, my analysis follows the approach adopted by Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020).8Borjas (2017) adopts a similar approach to analyze undocumented workers in the CPS. The criteria include arriving to the US after 1980, having no US citizenship, not having previously served in the military, not being a government worker, not being born in Cuba, and not receiving public benefits (Social Security Income, insurance through Medicare/Medicaid, and food stamps). An individual who meets all the criteria is then classified as a likely undocumented immigrant.

Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020) also use “not working in universally licensed professions” to define the undocumented population.9The list of universally licensed professions can be found in Gittleman et al. (2018). Because some granted professions under the CA law overlap with the universally licensed professions, I do not use this criterion since becoming licensed is the main channel through which the employment effect of the CA law operates.

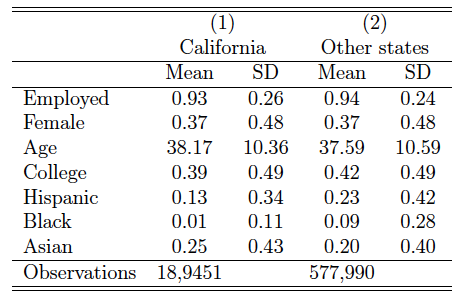

My sample consists of the working-age population (18–64) who are in the labor force. Table 1 shows the summary statistics of individual characteristics of likely undocumented immigrants in my 10-year repeated cross-sectional sample. Among the characteristics, California has fewer black and Hispanic immigrants than other states. My sample also has fewer women in general since I focus on workers who are in the labor force.

Table 1. Demographic Statistics of Likely Undocumented Immigrants

Data: American Community Survey (2009–2019).

Note: The sample consists of likely undocumented immigrants following the criteria (except universal licensure) by Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020), with those who are between 18 and 65 years old and in the labor force. Sample weights apply.

In the regression analysis, I employ the generalized DID approach that compares the individual outcome of undocumented immigrants in California with their counterparts in other states before and after 2014. Formally, I estimate

(1)

The outcome of interest equals 1 if worker i is employed in state s in year t. CABill is the treatment indicator for California after 2014, is vector of individual characteristics listed in Table 1, and

is a vector of time-varying state control variables tabulated using the ACS with sample weights. The variables include the share of minority workers, share of workers in manufacturing jobs, share of workers in the service sector, and the state population’s college attainment rate. The tabulation sample is restricted to the 18–64 population.

and

are year and state fixed effects, respectively. Standard errors are clustered at the state level to allow for serial correlation and to avoid underestimating confidence intervals. All regressions are weighted by the sample weight.

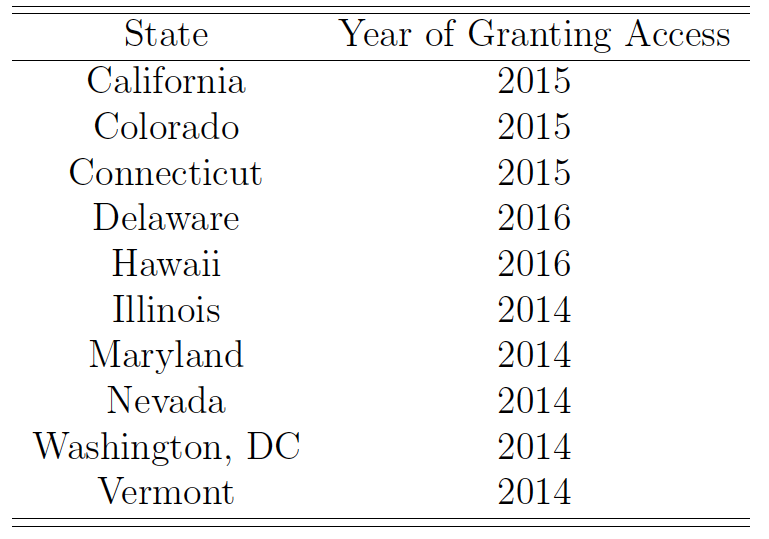

Although the model in Equation 1 controls for time-varying state-level changes, several states including California also granted undocumented immigrants access to driver’s licenses, which can be a competing concurrent policy since 2014. To address this confounding factor, I also control for the driver’s license policy in the regression.10The states are Washington, DC, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, and Vermont in 2014; California, Colorado, and Connecticut in 2015; and Delaware and Hawaii in 2016. See more details in appendix Table A3.

Results

Main Patterns

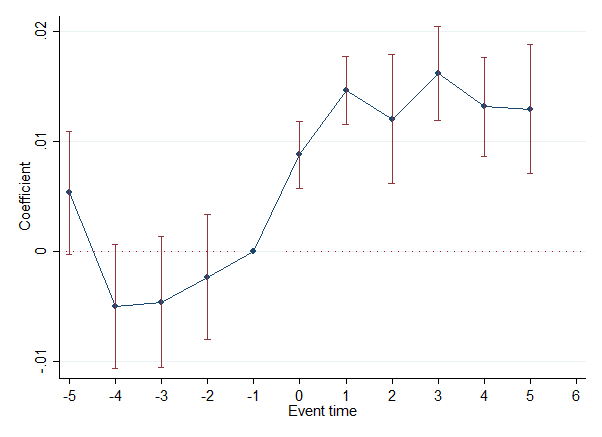

Figure 1 plots the raw pattern of the policy treatment by running a two-way fixed effects event-study model with no control variables. Formally,

(2)

While the pretreatment trend is slightly bumpy, the deviation is not statistically significant. To check the sensitivity of my DID estimate, I run an alternative model that applies matching to observables in Section 4.2. For the posttreatment years, there is a one-time jump in the employment likelihood of likely undocumented immigrants. The heterogeneity by occupation discussed later offers possible explanations for this discrete jump.

Figure 1. Event-Study Dummies Conditional on Fixed Effects

Data: American Community Survey (2009–2019).

Note: The figure shows the dynamic effects of the CA law, with 2014 being the omitted year. The regression only includes the year and state fixed effect. The point plots the estimate and the error bar represents the corresponding 95 percent confidence interval.

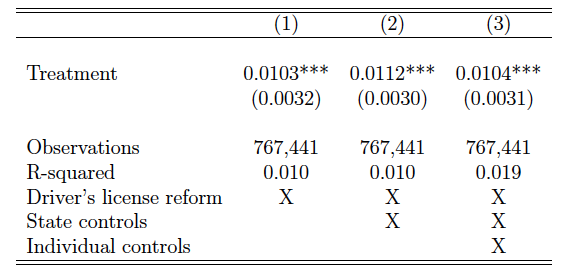

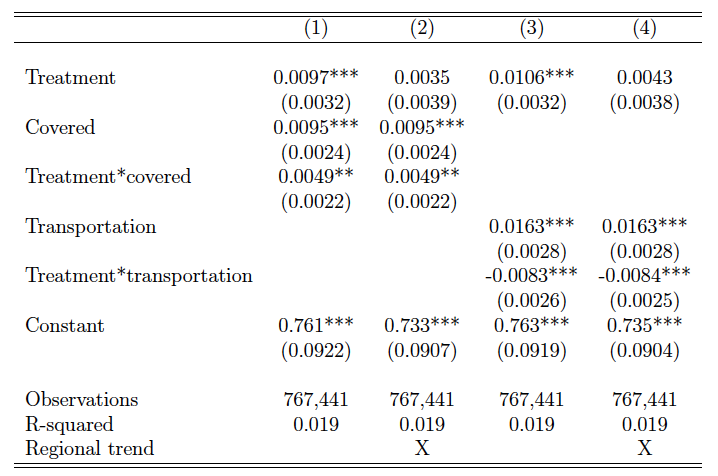

Table 2 presents the DID results, and column 1 reports the treatment effect conditional on fixed effects and controlling for the implementation of the driver’s license reform. Although the relaxation of driver’s license applications for undocumented immigrants overlaps with the occupational licensing reform, the treatment effect in my model remains significant at the 5 percent level. One way to interpret the coefficient is the effect of granting access conditional on the influence of the driver’s license reform. Section 5.1 further differentiates the two competing policies.

In columns 2 and 3, the treatment effect remains salient at the 5 percent level when further controlling for state and individual characteristics specified in Equation 1. In the fully saturated model in column 3, the CA law increases the employment of likely undocumented immigrants by about 1 percentage point. While the magnitude is small and constrained by the limited scope of the law, the effect size is still statistically significant.

Table 2. Main Result: DID Estimate with Different Specifications

Data: American Community Survey (2009–2019).

Note: The dependent variable equals 1 if the individual is employed. The sample is restricted to likely undocumented immigrants following the criteria (except universal licensure) by Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020), with those who are between 18 and 65 years old and in the labor force. All regressions control for year and state fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the state level. ***, ** and, * represent 1 percent, 5 percent, and 10 percent significance levels, respectively.

Sensitivity Check

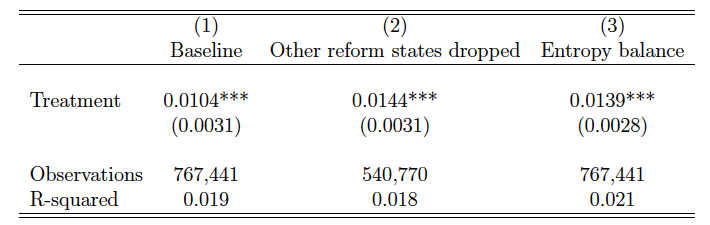

In this subsection, I check the validity of the DID estimate. Column 1 of Table 3 first reports the DID estimate in the fully saturated model as the baseline comparison. In the following exercises, the regressions follow the same specification as in column 3 of Table 2.

I first check the validity of the comparison states. As shown in appendix table A1, several liberal states also lift license restrictions for undocumented immigrants to some extent. In other words, putting these ‘quasi-treated’ states in the comparison group is analogous to the “bad comparison” problem induced by heterogeneous treatment timing (Baker et al., 2022). In column 2 of Table 3, the DID estimate is larger, by about one standard deviation, if I drop states with a similar licensure initiative. This implies that the changing employment trend in other states nullified the true treatment effect of the CA law if they are put in the comparison group.

Table 3. Sensitivity Checks: Sample Selection and Matching

Data: American Community Survey (2009–2019).

Note: The dependent variable equals 1 if the individual is employed. The sample is restricted to likely undocumented immigrants following the criteria (except universal licensure) by Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020), with those who are between 18 and 65 years old and in the labor force. All regressions control for individual and state characteristics, the timing of the driver’s license reform, and year and state fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the state level. ***, ** and, * represent 1 percent, 5 percent, and 10 percent significance levels, respectively.

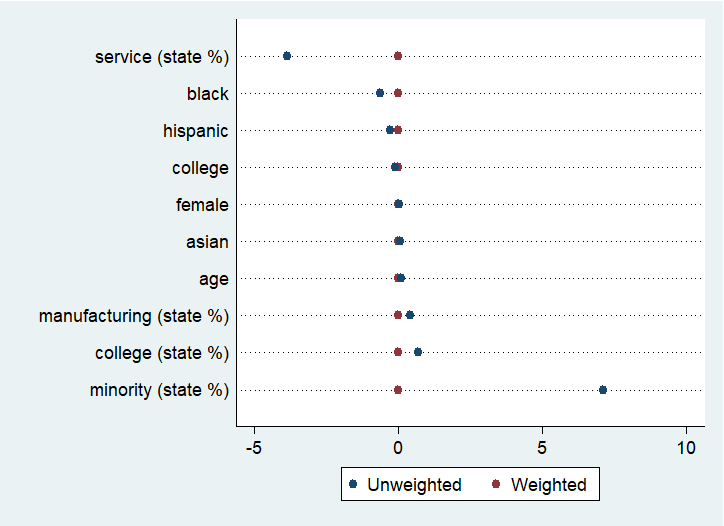

I then apply matching to the DID regression as the second check. I match likely undocumented workers in California with those in the comparison states using EB (Hainmueller, 2012), which is a recent matching technique used to obtain more comparable treatment and control groups based on observables. Compared to other common matching methods, such as coarsened exact matching, the EB method allows smoother weighting across units and avoids dropping observations. As shown in appendix figure A1, the covariate imbalance in both individual and state characteristics is drastically reduced under the weighting scheme. The notable changes occur to the size of the service sector and the minority population. When applying EB to the regression analysis in column 3 of Table 3, the estimate remains salient and the effect size is similar to the baseline in column 1.

Further Analysis

Differentiating the CA Law from the Driver’s License Reform

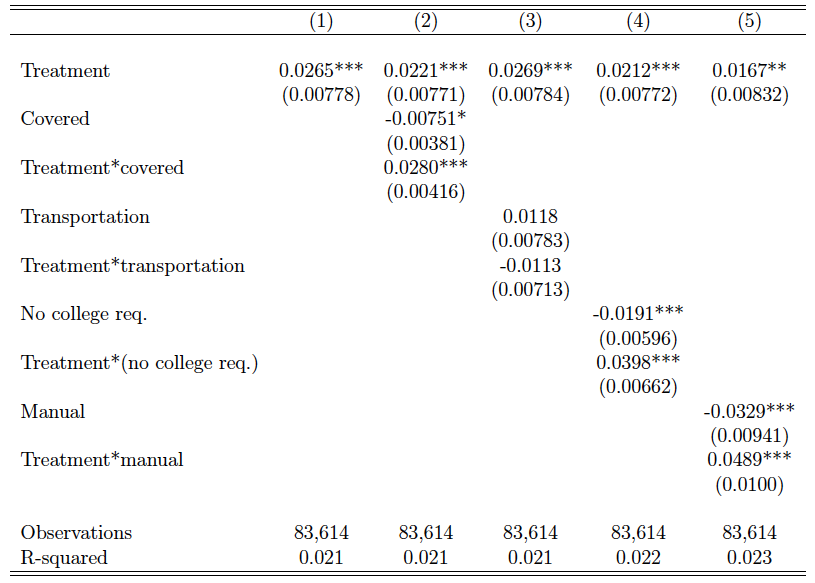

The driver’s license reform in California, which was effective in January 2015, has an overlapping window with the occupational licensing reform (CA law) this paper studies. In the main regression, when the model controls for the timing of the driver’s license reform in different states, I still observe a treatment effect from the CA law. From a statistical standpoint, the treatment dummy is an interaction term that captures additional influences of the CA law conditional on the average effect of the driver’s license reform. In this subsection, I provide more evidence to differentiate the CA law from the driver’s license reform.

Since the CA law only applies to the 39 license bureaus, a useful exercise is to differentiate the effect on the covered professions from that on other occupations. The idea is if the employment effect identified in the main analysis is driven by the CA law and not other confounding progressive policies, I should observe a stronger effect on covered professions. I start by matching the professional licenses administered by the covered license bureaus in Table A2 with the four-digit occupation code in the CPS using the O*NET-SOC AutoCoder. The AutoCoder software is an online application offered by the US Department of Labor for researchers to relate occupational information to the occupation classification system in national household surveys.

I use the license titles to obtain the best-match six-digit SOC codes in AutoCoder. I then transform the six-digit SOC codes to the four-digit codes in the CPS using the crosswalk provided by the US Census Bureau.11The crosswalk is publicly available at https://www.census.gov/topics/employment/industry-occupation/guidance/code-lists.html. For example, a security guard license under the Bureau of Security and Investigative Services is coded as 33-9032 in AutoCoder, which matches with 3930 in the CPS using the crosswalk. In the regression, the treatment dummy further interacts with an indicator of these covered professions, which is analogous to a triple-difference model. Column 1 of Table 4 reports the results of the triple-difference regression. The advantage of this model is that I can differentiate the impacts on the covered licensed occupations from other professions. The base treatment indicator may capture the residual influences on “uncovered” professions impacted by the driver’s license reform. My focus is the third-difference term (treat*cover), which captures the intended policy impact. The coefficient indicates that the CA law has a significantly differential impact on the employment of undocumented immigrants in covered professions. Combining terms, the CA law increases their employment in covered professions by about 1.5 percentage points.

Another exercise to differentiate the CA law from the driver’s license reform is a falsification test. Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020) identify a particular impact on transportation-related professions by driver’s license reforms. The availability of a driver’s license significantly raises the propensity of working as a driver (e.g., bus, ambulance, truck, taxi, chauffeur vehicles). Therefore, if the estimate of the CA law captures only the residual impact of the driver’s license reform, I should observe the same particular effect on the transportation occupations but not in the other covered professions.

In column 3 of Table 4, I run a placebo test by interacting the CA law indicator with a transportation dummy. The third-difference term has the opposite effect, and the overall placebo effect (treat + treat * transportation) is also economically small compared to the combined effect on covered professions in column 1. The result in column 3 falsifies the potential issue over the residual influence of the driver’s license reform.

In both exercises, I also check the sensitivity by including a regional trend in columns 2 and 4, respectively. While the specification might be overrestrictive, the qualitative result of the differential effect on covered professions and the placebo test on transportation occupations remain unchanged.

Table 4. Differences with Driver’s License Reform: Heterogeneity by Occupations

Data: American Community Survey (2009–2019).

Note: The dependent variable equals 1 if the individual is employed. The sample is restricted to likely undocumented immigrants following the criteria (except universal licensure) by Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020), with those who are between 18 and 65 years old and in the labor force. All regressions control for individual and state characteristics, the timing of the driver’s license reform, and year and state fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the state level. ***, ** and, * represent 1 percent, 5 percent, and 10 percent significance levels, respectively.

Heterogeneity

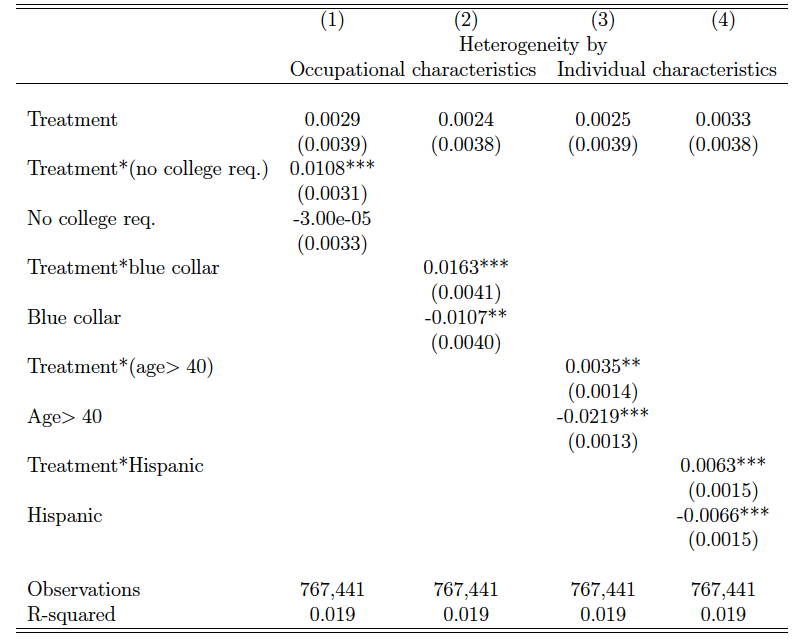

The distributional effect offers useful insights to policymakers to evaluate the effectiveness of the CA law. This subsection explores heterogeneity by occupational and individual characteristics to identify different impacts experienced by the subpopulation.

I first look at the interaction effect on whether the licensed professions require a college degree. As in Table A2, denoted with an asterisk, 10 of the license boards do not require a college qualification for their licenses. These professions include barbers and cosmetologists, pest control workers, practical/vocational nurses, psychiatric technicians, security guards, different types of contractors, auto mechanics, home service workers and repair people, funeral workers and directors, locksmiths, and court clerks. The interaction term in column 1 of Table 5 reveals that the CA law has a significantly larger effect on licensed professions that do not require a license, with a combined effect of 1.9 percent, which is double the effect size in the baseline model.

Licenses that do not have an education requirement usually take a shorter time to obtain, potentially explaining the immediate effect in the event-study graph in Figure 1. Aligning with the differential effects by education requirements, in column 2 of Table A2 I also observe a stronger impact on blue-collar workers, whose occupations fall into the “construction and extraction” category in the CPS code system. The heterogeneity here highlights that the policy elasticity is stronger among professions that do not require a college degree. Hence, the CA law does not seem effective enough to influence the labor supply of the higher-educated undocumented population.

In the next panel, I evaluate the heterogeneity by demographic characteristics. By interacting the treatment effect by age and ethnicity, columns 3 and 4 of Table A2 show that the CA law has a larger impact on older workers (age above 40) and Hispanic workers. The policy impact on Hispanic workers is even strong enough to close the employment gap with their non-Hispanic counterparts as indicated by the base term. The stronger effect on older workers also alleviates the concern over the residual influence of DACA, which approved SSNs (and thus the eligibility of licensure) before the CA law for young undocumented individuals (below the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012). Therefore, my estimate is less likely to pick up the confounding effect of DACA.

Table 5. Heterogeneity by Occupational and Individual Characteristics

Data: American Community Survey (2009–2019).

Note: The dependent variable equals 1 if the individual is employed. The sample is restricted to likely undocumented immigrants following the criteria (except universal licensure) by Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020), with those who are between 18 and 65 years old and are in the labor force. All regressions control for individual and state characteristics, the timing of the driver’s license reform, and year and state fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the state level. ***, ** and, * represent 1 percent, 5 percent, and 10 percent significance levels, respectively.

General Equilibrium Effect

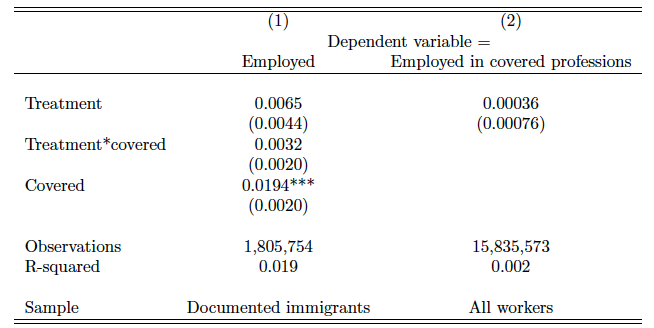

In this last section, I document the general equilibrium effect by evaluating the spillover on documented immigrants, the overall labor supply of covered professions, and undocumented workers’ occupation switching.

In column 1 of Table 6, I replicate the triple-difference model using the sample of documented immigrants.12I define documented immigrants as foreign-born workers who report their year of immigration to the US and do not satisfy the undocumented criteria by Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020). The base treatment indicator is significant and positive, which may imply a different state trend in the employment pattern of documented immigrants compared to other states after 2014. In contrast, the coefficient of the key interaction term is both economically and statistically small.

This null effect has two interpretations. First, one might worry that the main result on undocumented immigrants simply reflects the demand-side expansion in CA, either due to a positive economic shock in general or to a friendlier environment toward immigrants. The null effect on documented immigrants can serve as a placebo test against demand-side changes in covered professions. Second, the increase in employment of undocumented immigrants could mean a competition of job opportunities against documented immigrants. The nonnegative effect here implies that the CA law fulfils unmet consumer demands caused by the entry barrier before, instead of a zero-sum outcome of existing market transactions.

In column 2 of Table 6, I evaluate covered professions’ overall contribution to the labor supply in California. Following the specification by Law and Marks (2009), I run a linear probability two-way fixed effects model that regresses whether the worker works in covered professions on the CA law treatment dummy, individual and state control variables, and the timing of the driver’s license reforms. I do not find that the CA law significantly affects the overall labor supply in covered professions. This could be due to the heterogeneity results that I find regarding the CA law only impacting lower-education/blue-collar jobs, in which the impact size is relatively small at the aggregate level.

Table 6. Effects on Documented Immigrants and Overall Labor Supply

Data: American Community Survey (2009–2019).

Note: All regressions control for individual and state characteristics, the timing of the driver’s license reform, and year and state fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the state level. ***, ** and, * represent 1 percent, 5 percent, and 10 percent significance levels, respectively.

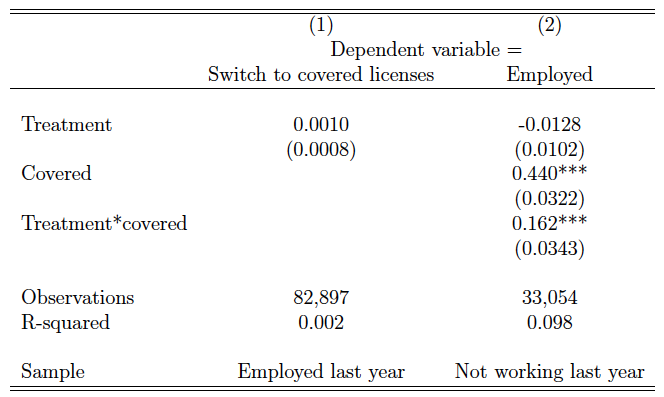

In the last exercise, I evaluate whether undocumented immigrants switch occupations. To assess switching, I analyze the March Supplement of the CPS (CPS March Supplement hereafter), which is another household survey that contains a national sample of US workers. To define the likely undocumented immigrants, I adopt the same criteria as used in the main analysis. While the CPS contains information on work history in the previous year, the sample size is 10 times smaller than that in the ACS, and therefore I only use the CPS March Supplement as a supplementary data. Nonetheless, in Table A4 I also observe the main patterns identified, namely that the CA law significantly increases the employment of likely undocumented immigrants in covered licensed professions, has no impact on the transportation sector, and has a stronger effect in lower-education/blue-collar occupations. In the regression, I explore whether the CA law caused preexisting workers in other fields to switch into covered professions. Focusing on undocumented workers who report working in the previous year, I regress whether a worker switches into covered professions in the current year on the policy indicator and the covariates in the main analysis. In column 1 of Table 7, I do not find a significant effect on occupation switching, both economically and statistically. I then assess if the CA law drew more undocumented individuals into employment. In column 2 of Table 7, I run the triple-difference model on undocumented immigrants who report not working in the previous year (either unemployed or not in the labor force). As indicated by the third-difference term, the CA law significantly increases their likelihood to work in covered licensed professions.

Table 7. Assessing Occupation Switching Using CPS

Data: CPS March Supplement (2009–2019).

Note: The sample is restricted to likely undocumented immigrants following the criteria (except universal licensure) by Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2020), with those who are between 18 and 65 years old. All regressions control for individual and state characteristics, the timing of the driver’s license reform, and year and state fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the state level. ***, ** and, * represent 1 percent, 5 percent, and 10 percent significance levels, respectively.

Conclusion

Exploiting the 2014 occupational license policy change in California, this paper finds that lifting occupational licensing restrictions on undocumented immigrants increased their employment in covered licensed professions. However, the effect did not occur for every covered occupation as I find stronger influences in lower-education and blue-collar professions. This potentially explains the immediate impact of the policy since these licenses have fewer requirements than higher-education/white-collar ones. In contrast, the policy did not increase employment in the transportation sector, which elucidates its difference with the driver’s license reforms. These patterns replicate in both the ACS and CPS March Supplement.

While states have gradually been establishing a more welcoming environment for hard-working immigrants, this paper shows that higher-wage jobs are still unreachable for some who have limited access to higher education or vocational training programs. One solution is to expand access to apprenticeship programs, which provide low-cost training options that help lower-educated individuals accumulate human capital and climb the social ladder.

Appendix I: Additional Background Information

Table A1. Summary of Lifting License Restrictions for Immigrants

Source: Williams (2019), Grelewicz (2020).

Table A2. License Boards under the California DCA

Source: Official Website of DCA (https://www.dca.ca.gov/about_us/entities.shtml).

∗ Not requiring a college degree

Table A3. States That Granted Driver’s License Access to Undocumented Immigrants

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures (https://www.ncsl.org/immigration/states-offering-drivers-licenses-to-immigrants), Cho (2022).

Note: The policy control in the regression is based on the effective date in the above website.

Appendix II: Additional Results

Figure A1. More Balanced Covariates with Entropy Balancing

Table A4. Replication of Main Patterns Using CPS

Data: CPS March Supplement (2009–2019).

Note: All regressions control for individual and state characteristics, the timing of the driver’s license reform, and year and state fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the state level. ***, ** and, * represent 1 percent, 5 percent, and 10 percent significance levels, respectively.

References

Alvarez, R. Michael and Tara L. Butterfield, “The resurgence of nativism in California? The case of Proposition 187 and illegal immigration,” Social Science Quarterly, 2000, 167–179.

Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina, Esther Arenas-Arroyo, and Almudena Sevilla, “La- bor market impacts of states issuing of driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants,” Labour Economics, 2020, 63, 101805.

Arroyo, Esther Areans and Bernhard Schmidpeter, “Spillover effects of immigration policies on children’s human capital,” 2022.

Baker, Andrew C., David F. Larcker, and Charles C.Y. Wang, “How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates?,” Journal of Financial Economics, 2022, 144 (2), 370–395.

Blair, Peter Q. and Bobby W. Chung, “How much of barrier to entry is occupational licensing?,” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 2019, 57 (4), 919–943.

and , “A model of occupational licensing and statistical discrimination,” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 2021, 111, 201–205.

and , “Job market signaling through occupational licensing,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 2022, pp. 1–45.

Borjas, George J., “The labor supply of undocumented immigrants,” Labour Economics, 2017, 46, 1–13.

Brucker, Herbert, Albrecht Glitz, Adrian Lerche, and Agnese Romiti, “Occupational recognition and immigrant labor market outcomes,” Journal of Labor Economics, 2021, 39 (2).

Cassidy, Hugh and Tennecia Dacass, “Occupational licensing and immigrants,” The Journal of Law and Economics, 2021, 64 (1), 1–28.

Cho, Heepyung, “Driver’s license reforms and job accessibility among undocumented immigrants,” Labour Economics, 2022, 76, 102174.

Chung, Bobby W. and Jian Zou, “Teacher licensing, teacher supply, and student achieve- ment: Nationwide implementation of edTPA,” Technical Report, HCEO Working Paper 2021.

Churchill, Brandyn F., Taylor Mackay, and Bing Yang Tan, “Driver’s licenses for unauthorized immigrants and auto insurance,” The Center for Growth and Opportunity, 2023.

Citrin, Jack, Donald P. Green, Christopher Muste, and Cara Wong, “Public opinion toward immigration reform: The role of economic motivations,” The Journal of Politics, 1997, 59 (3), 858–881.

Federman, Maya N., David E. Harrington, and Kathy J. Krynski, “The impact of state licensing regulations on low-skilled immigrants: The case of Vietnamese manicurists,” American Economic Review, 2006, 96 (2), 237–241.

Gittleman, Maury, Mark A. Klee, and Morris M. Kleiner, “Analyzing the labor market outcomes of occupational licensing,” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 2018, 57 (1), 57–100.

Gomez, Rafael, Morley Gunderson, Xiaoyu Huang, and Tingting Zhang, “Do immigrants gain or lose by occupational licensing?,” Canadian Public Policy, 2015, 41 (Supplement 1), S80–S97.

Grelewicz, Josh, “Are occupational licensing restrictions binding for undocumented immi- grants? Evidence from California,” 2020.

Hainmueller, Jens, “Entropy balancing for causal effects: A multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies,” Political Analysis, 2012, 20 (1), 25–46.

Kleiner, Morris M., “Occupational licensing,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2000, 14 (4), 189–202.

and Alan B. Krueger, “Analyzing the extent and influence of occupational licensing on the labor market,” Journal of Labor Economics, 2013, 31 (S1), S173–S202.

Lara, Ricardo, “Realizing the DREAM: Expanding access to professional licenses for California’s undocumented immigrants,” Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy, 2014, 27, 26.

Law, Marc T. and Mindy S. Marks, “Effects of occupational licensing laws on minorities: Evidence from the progressive era,” The Journal of Law and Economics, 2009, 52 (2), 351– 366.

Massey, Douglas S. and Kerstin Gentsch, “Undocumented migration to the United States and the wages of Mexican immigrants,” International Migration Review, 2014, 48 (2), 482–499.

Olivas, Michael A., “Within you without you: Undocumented lawyers, DACA, and occupational licensing,” Valparaiso University Law Review, 2017, 52, 65.

Passel, Jeffrey S., “Undocumented immigration,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1986, 487 (1), 181–200.

Peterson, Brenton D., Sonal S. Pandya, and David Leblang, “Doctors with borders: Occupational licensing as an implicit barrier to high skill migration,” Public Choice, 2014, 160 (1), 45–63.

Plemmons, Alicia, “Occupational licensing effects on firm entry and employment,” The Center for Growth and Opportunity, 2023.

Rubalcaba, Joaquin, Jos´e R Bucheli, and Camila Morales, “Immigration enforcement and labor supply: Hispanic youth in mixed-status families,” The Center for Growth and Opportunity, 2023.

Ruggles, Steven, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Megan Schoueiler, and Matthew Sobek, “IPUMS USA: Version 12.0,” 2022. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2023-2-28. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V12.0.

Sheehan, Kathleen and Diana Thomas, “Gender, race, and earnings: The divergent effect of occupational licensing on the distribution of earnings and on access to the economy,” The Center for Growth and Opportunity, 2023.

Tani, Massimiliano, “Occupational licensing and the skills mismatch of highly educated migrants,” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 2020.

Warren, Robert, “Reverse migration to Mexico led to US undocumented population decline: 2010 to 2018,” Journal on Migration and Human Security, 2020, 8 (1), 32–41.

Williams, Christy, “Professional and occupational licenses for immigrants,” Technical Report, Catholic Legal Immigration Network 2019.

Xia, Xing, “Barrier to entry or signal of quality? The effects of occupational licensing on minority dental assistants,” Labour Economics, 2021, 71, 102027.

Orange County Register

Orange County Register Journal of Regulatory Economics

Journal of Regulatory Economics