Introduction

Administrative procedures constrain regulatory investigations.1Mathew D. McCubbins, Roger G. Noll & Barry R. Weingast, Administrative Procedures as Instruments of Political Control, 3 J.L., Econ. & Org. 261 (1987) [hereinafter “McNollGast 1987”]. But such procedures are not self-executing.2Scott Limbocker, William Resh & Jennifer Selin, Anticipated Adjudication: An Analysis of the Judicialization of the US Administrative State, 32 J. Pub. Admin. Res. and Theory 610 (2022). Regulated parties cannot benefit from administrative procedures unless and until their counsel makes use of such provisions before an agency or in court. Yet even though lawyers may choose which procedures may benefit a client in response to an administrative inquiry, lawyers, particularly those who organize through large law firms to serve global corporations, face institutional constraints that bias against identifying—or present financial disincentives or relational risks vis-à-vis regulators that lead them to ignore—certain procedural safeguards in the law. This institutional constraint derives from the reality that those industry clients choose regulatory counsel who maintain relationships with a given regulator and who will advise them as to how a would-be regulator or a court will interpret the law. Whether a law is likely to be enforced as a policy matter is distinct from whether a given economic product or service is prohibited or permitted by law, particularly in an environment where regulators investigate to determine whether jurisdiction exists. Industry players, therefore, price this discretion by hiring lawyers who make conservative predictions about what a regulator might do or what a court might conclude.3See, e.g., Ganesh Sitaraman, Industrial Policy, Warfighting, and the Creation of the Modern American State, Yale J. on Reg. Online (2022), https://www.yalejreg.com/nc/symposium-novak-new-democracy-08/ (“Regulation acted as a form of industrial policy.”). Entrepreneurs or small businesses in novel sectors unspecified by current regulatory jurisdiction often cannot afford regulatory counsel nor is compliance with the conservative prediction reasonable for companies facing barriers to market entry or growth. Moreover, regulatory counsel, whose fidelity will be to those clients providing repeat fees, will decline to represent those clients who are willing to evade compliance with their conservative predictions, for any such engagement threatens relationships with both incumbent clients and regulators. These realities present a federal regulatory state institutionally biased against small entrepreneurs.

In 2019, former President Trump sought to resolve the disproportionate harms administrative inquiries posed to small businesses and to those businesses that cannot afford large law firm counsel by restating extant public rights laws to identify available yet underutilized administrative procedures. Executive Order Number 13892 and Executive Order Number 13924 articulate statutory principles that, if subject to judicial review, would prohibit agencies from establishing policy through pre-enforcement investigations or adjudication without prior notice of the agency’s authority to do so.4Exec. Order No. 13892, Promoting the Rule of Law Through Transparency and Fairness in Civil Administrative Enforcement and Adjudication, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/10/15/2019-22624/promoting-the-rule-of-law-through-transparency-and-fairness-in-civil-administrative-enforcement-and (2019); Exec. Order No. 13924, Regulatory Relief to Support Economic Recovery, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/05/22/2020-11301/regulatory-relief-to-support-economic-recovery (2020). The big idea was to ensure nonpublic pre-enforcement inquiries by agencies complied with procedurally established due process protections even absent a petition by a well-resourced regulated party. Here, small businesses, notwithstanding their inability to afford expert counsel, would reap the benefits of administrative procedures. On January 20, 2021, and February 24, 2021, President Biden rescinded Executive Order Numbers 13892 and 13924, respectively.5Executive Order No. 13992, Revocation of Certain Executive Orders Concerning Federal Regulation, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/executive-order-revocation-of-certain-executive-orders-concerning-federal-regulation/ (2021); Executive Order No. 14018, Revocation of Certain Presidential Actions, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/03/01/2021-04281/revocation-of-certain-presidential-actions (2021).

In this Article, I identify a number of procedural safeguards that are often overlooked in regulatory litigation against the bureaucracy. In Part I, I outline those “due process” procedures that constrain agency investigations yet are both underexamined by scholars and underutilized by practitioners. These include the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA), which regulates general investigations as “information collections” and the original public rulemaking requirements of the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act (APA) now codified at 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(1)(D). This presents a puzzle given the substantial acceptance by both political scientists and administrative law scholars of the theory that administrative procedures are the primary mechanism through which Congress ensures oversight over the bureaucracy.6McNollGast 1987, supra note 1; Lisa Schultz Bressman, Procedures as Politics in Administrative Law, 107 Colum. L. Rev. 1749 (2007); Randall L. Calvert, Mathew D. McCubbins & Barry R. Weingast, A Theory of Political Control and Agency Discretion, 33 Am. J. of Pol. Sci. 588 (1989). I suspect that for certain litigants, confronting the uncertainties and risks in judicial agenda setting concerning regulation (i.e., judicial discretion and deference) is necessary for their survival. But market incumbents can absorb the cost of pre-enforcement settlements and benefit when the absence of rules harms would-be competitors, disincentivizing business-side lawyers from bringing legal challenges to regulatory inquiries on behalf of individual entities.

In Part II, I contend that despite the clear remedies provided under the statutory rights discussed in Part I, regulated parties do not avail themselves of these remedies. I argue that this fact is suggestive of how we should think about “power” in the administrative state. I question why certain quasi-due process procedures often lie fallow, and I have developed an empirical model that contributes to the legal understanding of the federal regulatory state. The received legal view of executive power suggests that the president, through his appointees, chooses not to enforce these due process features. My first empirical model tested this received view and rejected it by showing that strategic litigants can shape legal outcomes affecting the executive branch through forum selection on administrative law claims. That successful regulatory challenges require strategic agenda setting by litigants is suggestive of the pluralistic, rather than unitary, nature of regulatory power. To say that administrative power is pluralistic is to say that administrative power is not concentrated in political officials but rather in the regulated parties who set those officials’ decision-making agenda. And yet regulated parties are not routinely advised by their counsel to secure quasi-due process rights, such as the requirement that agency jurisdictional statements be publicly noticed in advance, that all investigations must be for a rulemaking purpose, or that regulatory inquiries of industry members are information collections subject to Office of Management and Budget (OMB) review, approval, and notice and comment. The only rule of law justification for administrative procedures being dependent on regulated parties is to claim that the legal status of administrative investigations is excluded from the regulatory process. In other words, administrative inquiries are auxiliaries to law enforcement. Alternatively, it may be the case that administrative investigations are subject to regulatory procedures, but those procedures are not enforced by the legal representatives of regulated parties and thus must depend upon Congress or the courts for their enforcement.

In Part III, I hypothesize that the underutilization of these procedural tools by counsel is based upon a legal norm that bureaucratic investigations are adjuncts to the executive law enforcement power. As such, rather than inform bases for affirmative litigation challenges, administrative subpoenas inform counsel of the need to represent their client in a defensive posture. I show how Supreme Court jurisprudence prior to the APA made clear that pre-enforcement agency investigations are “legislative” in nature, not acts of law enforcement, but argue that the post-Nixon7United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1974). Supreme Court’s skepticism as to the continuing validity of Humphrey’s Executor v. United States8Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, 295 U.S. 602 (1935). has meant the reordering of administrative subpoenas as “executive” not “legislative” in nature. I briefly summarize empirical evidence showing that Congress has delegated its investigative powers over time to the bureaucracy. I then investigate what regulatory pluralism, as a model of the administrative state, means for pre-enforcement regulatory inquiries. If pluralism is a workable model for the administrative state, then it should have strong explanatory power for administrative activities that are alleged not to constitute rulemaking or adjudication, as is suggested with administrative subpoenas.

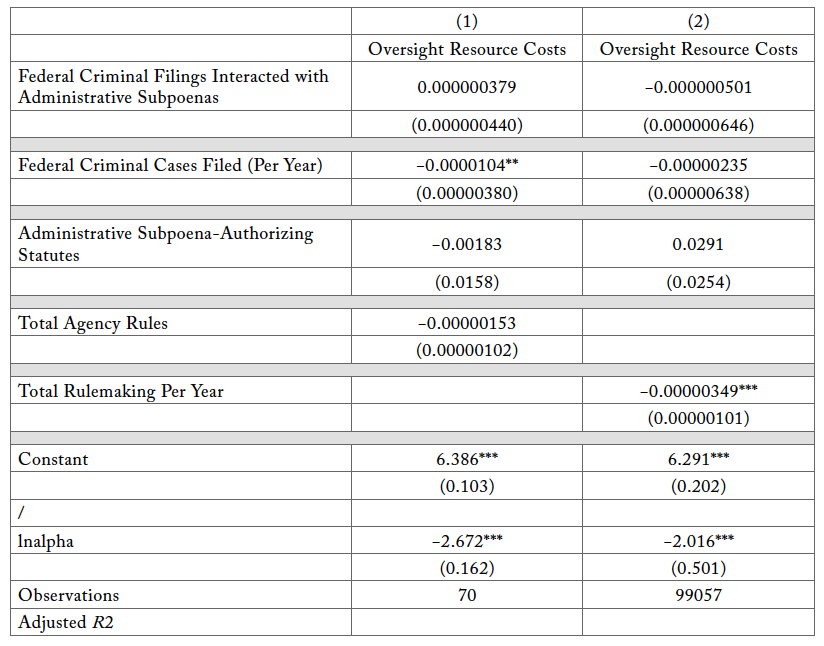

In my second empirical model, I expand upon my research showing that Congress delegates its investigative powers to the bureaucracy in order to maximize the electoral benefits of direct congressional oversight.9See discussion of political science scholarship in Jacob E. Gersen & Anne Joseph O’Connell, Deadlines in Administrative Law, 156 U. Pa. L. Rev. 923, 926, n. 11 (2008). My prior work showed that although Congress prefers ex ante methods of oversight, viz., private rights of action under statutes like the APA in order to constrain the executive branch, it still conducts ex post hearings and does so to maximize its electoral rewards. Because Congress may delegate administrative subpoena authorities to the executive branch and then rationally maximize electoral reward when those powers are used for law enforcement activities, I add executive branch law enforcement activities as an instrumental variable that I theorize mediates the relationship between, on the one hand, legislative delegation of investigative powers in the form of administrative subpoenas and, on the other, congressional oversight. I find, however, that increases in executive branch law enforcement activities do not advance Congress’s electoral goals. If, as scholars suggest,10See infra note 6. Congress’s preferred method of oversight over delegated power is through indirect monitoring via establishing administrative procedures, then we should be skeptical of the idea that administrative subpoenas are delegations of legislative power or otherwise skeptical of the use of administrative subpoenas as adjuncts to law enforcement, rather than agency rulemaking or adjudication. The results of this model suggest that doctrinal distinctions between executive versus legislative power within the bureaucracy are important within the context of separation of powers and democratic accountability. While the law distinguishes between “administration,” “implementation,” or “enforcement” of legal authority and formal “law enforcement,” virtually everything the executive branch does is law enforcement. In this sense, the federal regulatory state—an enforcement state—is representative of a strong unified executive. Yet in the unified enforcement executive, power is not centralized in the president with deference by the federal courts but is dispersed toward, or delegated to, the specially interested litigants who set the administrative agenda.

In Part IV, I conclude by outlining the implications of the arguments and empirical evidence marshaled herein for administrative law. The theory of the administrative state as both a unitary enforcement state and one governed by a pluralistic theory of power means that improving regulatory due process depends, in part, upon the ability for lawyers to inform the judicial decision-making agenda on administrative law. But the pluralistic enforcement state is a cautionary tale, for the diffusion of power to those without formal accountability raises legitimacy concerns, particularly given the unique problems of agency capture. And alternatives to the pluralistic enforcement state, for example, the nondelegation doctrine, may be impractical as the political evolution of administrative politics has ossified over time. It appears we may have achieved a unitary executive branch in form but pluralism in substance. I make the case for rethinking pre-enforcement agency investigations as legislative rulemaking, versus executive enforcement, as a solution to an executive defined by unified enforcement yet pluralistic power.

Underutilized Due Process Protections against Regulatory Inquiries

Informal investigations represent the primary manner in which federal agencies make regulatory policy.11Rory Van Loo, Regulatory Monitors, 119 Colum. L. Rev. 369, 408 (2019). In one year, the federal bureaucracy issued 3,367 rules compared to 397,834 adjudications.12Limbocker et al., supra note 2. Executive branch agencies and departments with law enforcement powers use “voluntary information requests,” “requests for information,” or “administrative investigations” or “inquiries” to obtain information concerning individuals’ and businesses’ noncompliance with statutes. Such voluntary information requests are often sent to a class of industry members if the agency or department is concerned that certain business sectors may not be complying with a statute. These voluntary information requests can lead to information that leads to further compulsory requests and subsequent enforcement activities.

Legal practitioners defend against these investigations as if they are indistinguishable from compulsory process in the form of congressional, grand jury, or administrative subpoenas. Yet unique rules apply to regulatory inquiries that do not apply to congressional or traditional law enforcement inquiries. Two crucial sets of rules derive from the statutes codified under Title 5 and Title 44 of the United States Code (U.S.C.), which set forth the metes and bounds of federal information law. Two notable laws include the PRA, which regulates general investigations as “information collections,” and the original public rulemaking requirements of the 1946 APA now codified at 5 U.S.C. 552(a)(1)(D) (the Freedom of Information Act or FOIA).13Because I argue in Part IV that our administrative law requires political rethinking, it should be noted at the outset that no post-Nixon president has evaded political oversight grounded upon either Title 5 or 44.

PRA Protections

All federal agency investigations collect information. The PRA regulates federal agency14“[A]ny executive department, military department, Government corporation, Government controlled corporation, or other establishment in the executive branch of the Government (including the Executive Office of the President), or any independent regulatory agency[.].” 44 U.S.C. § 3502(1). collections of information from third parties or the public. Under the Act, information collections cover the obtaining or soliciting facts or opinions to, or identical reporting or record-keeping requirements imposed on 10 or more persons.1544 U.S.C. § 3502(2). OMB has interpreted the Act’s information-collection requirements concerning “ten or more persons” to mean that “[a]ny recordkeeping, reporting, or disclosure requirement contained in a rule of general applicability is deemed to involve ten or more persons. Any collection of information addressed to all or a substantial majority of an industry is presumed to involve ten or more persons.”165 C.F.R. § 1320.3(c)(2).

The PRA requires that an OMB control number be displayed on every “information collection request” that is subject to OMB review.1744 U.S.C. § 3507(f). In particular, the PRA requires that an information collection is “inventoried, displays a control number and, if appropriate, an expiration date; . . . informs the person receiving the collection of information of . . . the reasons the information is being collected; the way such information is to be used; an estimate, to the extent practicable, of the burden of the collection; whether responses to the collection of information are voluntary, required to obtain a benefit, or mandatory; and the fact that an agency may not conduct or sponsor, and a person is not required to respond to, a collection of information unless it displays a valid control number[.]”1844 U.S.C. § 3506(c)(1). Only criminal, civil, or administrative law enforcement investigations and proceedings against specific individuals or entities are exempt from OMB review under the PRA.1944 U.S.C. § 3518(c)(1)(B)(ii). An “administrative action or investigation involving an agency against specific individuals or entities” is distinguished under the PRA from “the collection of information during the conduct of general investigations . . . undertaken with reference to a category of individuals or entities such as a class of licensees or an entire industry.”20Compare 44 U.S.C. § 3518(2), with 44 U.S.C. § 3502(2).

Beyond these procedures, agency information collections are subject to public notice and comment requirements.2144 U.S.C. § 3518(c)(2) (“provide 60-day notice in the Federal Register, and otherwise consult with members of the public and affected agencies concerning each proposed collection of information, to solicit comment to evaluate whether the proposed collection of information is necessary for the proper performance of the functions of the agency, including whether the information shall have practical utility; evaluate the accuracy of the agency’s estimate of the burden of the proposed collection of information; enhance the quality, utility, and clarity of the information to be collected; and minimize the burden of the collection of information on those who are to respond, including through the use of automated collection techniques or other forms of information technology”). The PRA states, “An agency shall not conduct or sponsor the collection of information unless in advance of the adoption or revision of the collection of information . . . the agency has conducted the review established under section 3506(c)(1), evaluated the public comments received under section 3506(c)(2),” published a notice of the information collection in the Federal Register, and received OMB approval of the information collection.2244 U.S.C. § 3507(a). Finally, the PRA specifically requires that agencies not only meet the Small Business Act (SBA) mandate2315 U.S.C. § 632. to reduce information collection burdens on small businesses, but that they “make efforts to further reduce the information collection burden for small business concerns with fewer than 25 employees.”2444 U.S.C. § 3506(c)(4).

Federal tax returns are perhaps the most visible example of OMB-approved forms the bureaucracy uses to collect information. Yet even information collections contained in a rule of general applicability25See Part I.C. or requested from a substantial majority of an industry are subject to PRA requirements. As a technical matter, the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) requests for information (RFIs) from peer-to-peer file-sharing companies or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) RFIs to payment card data processors arguably should have been subject to the PRA requirements of having a control number approved by OMB and subject to advance notice and comment. In what is arguably a form of PRA structuring, agencies like the CFPB and FTC will send RFIs to nine recipients on the grounds that the PRA does not apply. Yet while such requests avoid the magic “ten or more persons” standard in the statute, OMB’s own interpretation requires procedural compliance even for requests to an industry of one.

The federal courts have recognized the necessity for agency information collections to undergo OMB review and approval.26See e.g., Dole v. United Steelworkers of Am., 494 U.S. 26, 33 (1990). Courts have also recognized that the PRA states that “no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to maintain or provide information to any agency if the information collection request . . . does not display a current control number assigned by the Director[.]”2744 U.S.C. § 3512; accord 5 C.F.R. 1320.6(a)(2) (“Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information that is subject to the requirements of this part if . . . [t]he agency fails to inform the potential person who is to respond to the collection of information . . . that such person is not required to respond to the collection of information unless it displays a currently valid OMB control number”). The difficulty, however, is determining when an agency investigation rises to the level of an information collection. Complicating this difficulty is the reality that courts have indicated that statutory requirements for information collections are outside the scope of judicial review under the PRA.28Taylor v. FAA, 895 F.3d 56, 69 (D.C. Cir. 2018).

Agencies and departments do not currently classify their voluntary information requests or subpoenas enforcing such requests as “information collections” required to be reviewed by the OMB or containing OMB approval numbers under the PRA. Nor does the federal bureaucracy state in their voluntary information requests that such requests are exempt from the PRA.

Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act Protections

The preamble to the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA) states its legislative purpose is “to provide relief from excessive and arbitrary regulatory enforcement actions against small entities.”29Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996, § 213(a), 110 Stat. 858-59, 5 U.S.C. § 601 note. Section 213 of SBREFA permits small entities to make inquiries “concerning information on and advice about compliance with” the statutes and regulations an agency enforces, requiring the agency to interpret and apply “the law to specific sets of facts supplied by the small entity.”30Id. § 213. Moreover, should an agency pursue a civil or administrative action against the small entity, “guidance given by an agency applying the law to facts provided by the small entity may be considered as evidence of the reasonableness or appropriateness of any proposed fines, penalties or damages sought against such small entity.”31Id. Section 223 of SBREFA requires “[e]ach agency regulating the activities of small entities shall establish a policy or program within one year of enactment of this section to provide for the reduction, and under appropriate circumstances for the waiver, of civil penalties for violations of a statutory or regulatory requirement by a small entity.”32Id. § 223.

SBREFA also created an Ombudsman who shall “work with each agency with regulatory authority over small businesses to ensure that small business concerns that receive or are subject to an audit, on-site inspection, compliance assistance effort, or other enforcement related communication or contact by agency personnel are provided with a means to comment on the enforcement activity conducted by such personnel.”3315 U.S.C. § 657(b)(2)(A). The statute itself defines “means to comment” as “to refer comments to the Inspector General of the affected agency in the appropriate circumstances.”34Id. § 657(b)(2)(B). In other words, enforcement abuse against small businesses is within the investigative responsibility of the Inspectors General. Section 231 of SBREFA states that “[i]f, in an adversary adjudication arising from an agency action to enforce a party’s compliance with a statutory or regulatory requirement, the demand by the agency is substantially in excess of the decision of the adjudicative officer and is unreasonable when compared with such decision, under the facts and circumstances of the case, the adjudicative officer shall award to the party the fees and other expenses related to defending against the excessive demand, unless the party has committed a willful violation of law or otherwise acted in bad faith, or special circumstances make an award unjust.”35Id. § 231.

The Supreme Court has never had occasion to analyze the small entity compliance provisions of SBREFA and few federal circuit courts have analyzed the law.36See Air Brake Sys. v. Mineta, 357 F.3d 632, 648 (6th Cir. 2004).

APA Protections

The public disclosure provisions of the APA require that each agency “separately state and currently publish in the Federal Register for the guidance of the public . . . substantive rules of general applicability adopted as authorized by law, and statements of general policy or interpretations of general applicability formulated and adopted by the agency; and each amendment, revision, or repeal of the foregoing.”375 U.S.C. § 552(a)(1)(D). Under the APA, if a person lacks “actual and timely notice of the terms thereof” then “a person may not in any manner be required to resort to, or be adversely affected by, a matter required to be published in the Federal Register and not so published.”38Id. While federal courts have examined these provisions in the context of informal rulemaking under section 553 of the APA,39See e.g., Humane Soc’y of the United States v. United States Dep’t of Agric., No. 20-5291, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 20232, at *1 (D.C. Cir. July 22, 2022). they have had less occasion to examine due process-style arguments in this vein in the context of agency enforcement.40Compare Humane Soc’y, id. to Barbosa v. United States Dep’t of Homeland Sec., 916 F.3d 1068, 1074 (D.C. Cir. 2019) (determining that 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(1) permits judicial review of adverse effects on parties but not judicial review of failure to promulgate regulations).

The APA’s public disclosure provisions clearly inform the information collection requirements of the PRA. A “rule of general applicability” – for instance an agency’s determination that it has jurisdiction over a particular act or practice – must be published in the Federal Register in advance of any collection of information from a party based upon such a determination. Further, such a collection of information must itself comply with the procedures established under the PRA.

Notwithstanding the general absence of particularized challenges to administrative inquiries on PRA grounds, the weight of jurisprudential evidence creates the presumption that such challenges would fail to be ripe. The PRA does not create a separate cause of action which means that challenges to administrative inquiries must be brought under the APA. The APA permits review of only “final agency action” where a “preliminary” or “procedural” agency action is subject to review only upon the final action of the agency415 U.S.C. § 704. – in the case of administrative inquiries that often means an enforcement complaint or, at minimum, a subpoena.

Administrative Neglect of Procedures

A number of agencies enforce statutes by issuing resolutions interpreting that agency’s authority over some form of conduct. These resolutions represent jurisdictional rules or rules of “general applicability.” However, these resolutions of jurisdiction are often not made accessible to the public through publication in the Federal Register. Further, agencies may use consent decrees or other settlement documents as a basis for establishing its statutory jurisdiction over public activities without publishing those documents or the standards promulgated therefrom. When regulators win enforcement cases before their commissions, they create “regulatory common law” that is given deference by reviewing courts. The Third Circuit, in Wyndham v. FTC, acknowledged the validity of the “common law” of consent decrees.

Issues related to such “secret law” were litigated before the FTC and the Eleventh Circuit by LabMD – a pathology business that qualified as a small entity under the size standards of the Small Business Act.42See Aram Gavoor & Steven Platt, Administrative Investigations, 97 Ind. L.J. 421 (2022). This article is rooted upon a number of cases where I developed the client and legal strategy (the first author was a lawyer at the firm I oversaw). These cases include In re LabMD (concerning the FTC’s enforcement of section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act against a cancer laboratory); Rhea Lana v. U.S. Department of Labor (where the question was presented as to whether a preliminary determination of liability constituted final agency action for purposes of judicial review under the APA); Consumer Product Safety Commission v. Maxfield and Oberton (d/b/a “Buckyballs”) (where Buckyballs was subject to a recall and penalty despite the lack of any actual evidence that its product harmed children); and Drakes Bay Oyster Company v. Salazar (concerning whether a Secretary’s decision to apply the National Environmental Policy Act’s environmental impact assessments (“EIS”) to an otherwise discretionary permit decision and then subsequently ignore the EIS in denying a permit created a right to judicial review), among others. The facts of LabMD have been described by other scholars.43Id. See also Geoffrey A. Manne and Kristian Stout, When ‘Reasonable’ Isn’t: The FTC’s Standardless Data Security Standard, 15 J.L. Econ. & Pol’y 67 (2019); Stuart L. Pardau & Blake Edwards, The FTC, the Unfairness Doctrine, and Privacy by Design: New Legal Frontiers in Cybersecurity, 12 J. Bus. & Tech. L. 227 (2017); Gus Hurwitz, Data Security and the FTC’s UnCommon Law, 101 Iowa L. Rev. 955 (2016). But the case is of interest for purposes of this article because all of the procedural requirements of the PRA, the APA and SBREFA were violated yet LabMD did not argue any of these specific provisions. Cases like LabMD informed Executive Order 13892 and a subsequent order at 13924.44See cases described in note 40, supra. I was the architect of E.O.’s 13892 and 13924.

Executive Order 13892

E.O. 13892 was titled, “Promoting the Rule of Law Through Transparency and Fairness in Civil Administrative Enforcement and Adjudication.” It framed the procedural requirements established by the PRA, SBREFA, and the APA in terms of “fairness” and “transparency.” That framing is interesting in its own right considering the constitutional conservatives who shaped policy in the Trump Administration are presumed to subscribe to unitary executive principles and largely reject the validity of Humphrey’s Executor.45See Part III, supra. “Fairness” and “transparency” are terms often used by good government groups and congressional overseers to describe the importance of the legislative power of regulatory oversight. Such oversight is framed in terms of constitutional checks over delegated legislative power.46David Epstein and Sharyn O’Halloran, Delegating Powers: A Transaction Cost Politics Approach to Policy Making Under Separate Powers (1999). The framing of E.O. 13892 in terms of fairness and transparency over administrative investigations echoes this sense that the APA is a constitutional check on delegated legislative investigative power. In this sense, the typology of regulatory fairness presumes the validity of delegation.

E.O. 13892 identifies the procedural requirements of the APA (and points out that the 1946 APA’s public disclosure requirements are now codified as the Freedom of Information Act) and specifically finds that “departments and agencies (agencies) in the executive branch have not always complied with these requirements. In addition, some agency practices with respect to enforcement actions and adjudications undermine the APA’s goals of promoting accountability and ensuring fairness.”47E.O. 13892, supra note 4 § 1. Further, E.O. 13892 specifically directs that “[a]gencies shall afford regulated parties the safeguards described in this order, above and beyond those that the courts have interpreted the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution to impose.”48Id.

E.O. 13892 also anticipated arguments that challenges to regulatory inquiries were not ripe under the APA. The E.O. defines “legal consequence” to mean “the result of an action that directly or indirectly affects substantive legal rights or obligations. . . . and includes, for example, agency orders specifying which commodities are subject to or exempt from regulation under a statute . . . as well as agency letters or orders establishing greater liability for regulated parties in a subsequent enforcement action. . . [i]n particular, ‘legal consequence’ includes subjecting a regulated party to potential liability.”49Id. § 2. E.O. 13892 clarifies pre-enforcement, informal (i.e., no subpoena or compulsory process), and voluntary inquiries as “final” for purposes of the APA due to the legal consequences that attach in virtue of the public disclosure and notice requirements under FOIA and the PRA.50Id. at § 4. Both such investigations as well as the use of investigations and adjudication to establish “jurisdictional determinations” must be predicated upon “standards of conduct that have been publicly stated in a manner that would not cause unfair surprise[.]”51Id. & id. § 5.

While not explicit, E.O. 13892 makes clear how it understands the legal status of bureaucratic requests for information. The E.O. structures agency inquiries as cabined by rules. If an agency seeks to establish its statutory jurisdiction over some conduct, product, or service it must first publish its jurisdictional determination in the Federal Register. The APA makes clear that “rulemaking” is the process of formulating a rule525 U.S.C. 551(5). and because “statements of policy” rules must structure inquiries and inquiries are auxiliaries to prospective rules, agency inquiries constitute rulemaking.

The concept of investigations as auxiliaries to standards of policy is central to the legislative inquiry power. When Congress investigates the private sphere for a “legislative purpose” it is revealing such an investigation as “legislative” in nature as opposed to an investigation whose purpose is to establish not merely legal consequences but legal penalties. E.O. 13892 thus makes the explicit distinction between agency investigations that are legislative in nature – and are therefore cabined by the APA and PRA – and agency investigations that enforce the law. In the simplest light, legislative investigations can be conceived as independent from the political oversight of the president whereas law enforcement inquiries are crucially subject to the chief executive’s purview.

Moreover E.O. 13892 adopts the standard of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure that any claim for an act or omission must clearly state the standards for which compliance was required53F.R.C.P. Rule 56(d)(1). and applies to how agencies proceed with enforcement notably independent of whether the agency proceeds before an Article III court or an in-house administrative law judge. As such, E.O. 13892 foreshadowed such cases like Jarkesy.54Jarkesy v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 34 F.4th 446, 449 (5th Cir. 2022).

What makes the Biden Administration’s rescinding of E.O. 13892 interesting is the extent to which E.O. 13892 simply stated the law versus established or ordered agencies to act. To be sure, the Order did seek agencies to publish rules of procedure governing agency inspections,55Note 4, supra at § 7. but that requirement is arguably already established in law.565 U.S.C. § 552(a)(1) et seq. Indeed one obvious aspect of E.O. 13892 as simply a restatement of law is that it seeks to avoid “PRA structuring” where agencies like the FTC and CFPB send voluntary RFIs to nine persons in order to avoid the ten person magic number that kicks in the PRA’s procedural requirements by clarifying that “any collection of information during the conduct of an investigation” must comply with the PRA.57Note 4, supra at § 8 (noting exceptions for inquiries arising under 44 U.S.C. § 3518, 5 C.F.R. § 1320.4, and 18 U.S.C. § 1968).

Executive Order 13924

The coronavirus pandemic occurred subsequent to the issuance of Executive Order 13892, prompting the issuance of an order to continue regulatory fairness in the form of Executive Order 13924 titled, “Regulatory Relief To Support Economic Recovery.” Like E.O. 13892, E.O. 13924 directed agencies to commit “to fairness in administrative enforcement and adjudication.”58E.O. 13924, supra note 4 § 1. Consistent with E.O. 13892, “administrative enforcement” is defined to include “investigations, assertions of statutory or regulatory investigations, and adjudications” thus, again, echoing a more ancient notion distinguishing between legislative and executive branch enforcement.59J.W. Hampton Jr. & Co. v. United States, 276 U.S. 394 (1928). E.O. 13924, like its predecessor, was rescinded by the Biden Administration. E.O. 13924 is more explicit about SBREFA’s procedural requirements concerning pre-enforcement guidance on compliance noted in section 6(a) of E.O. 13892 yet applies SBREFA’s benefit to small businesses to be able to obtain such guidance “without regard to the requirements of section 6(a) of Executive Order 13892” that is, independent of whether the entity is a small business. Despite E.O. 13924’s brief existence, it is notable for establishing a regulatory “Bill of Rights” in section 6, entitled “Fairness in Administrative Enforcement and Adjudication:”

- The Government should bear the burden of proving an alleged violation of law; the subject of enforcement should not bear the burden of proving compliance.

- Administrative enforcement should be prompt and fair.

- Administrative adjudicators should be independent of enforcement staff.

- Consistent with any executive branch confidentiality interests, the Government should provide favorable relevant evidence in possession of the agency to the subject of an administrative enforcement action.

- All rules of evidence and procedure should be public, clear, and effective.

- Penalties should be proportionate, transparent, and imposed in adherence to consistent standards and only as authorized by law.

- Administrative enforcement should be free of improper Government coercion.

- Liability should be imposed only for violations of statutes or duly issued regulations, after notice and an opportunity to respond.

- Administrative enforcement should be free of unfair surprise.

- Agencies must be accountable for their administrative enforcement decisions.60Supra note 4 at § 6.

As stated earlier, several of these principles are already codified within the federal public law. That an Order purportedly restating these extant legal principles has been rescinded – without legal challenge – is telling of a reality that administrative due process rights are intrinsic yet fallow. Part II seeks to explore why that is the case.

The Nature of Regulatory Power

In Part I, I examined statutes that restrain executive branch decision-making and noted their dormant nature in the sense that neither the president nor the executive branch agencies enforce these procedural requirements established by law. The two executive orders which sought to enforce these relevant statutes were both rescinded. What does it say about our administrative law that laws on the books may mean nothing if the sovereign – here, the chief executive, i.e., president – does not implement them? The discussion in Part I of this Article is suggestive of our administrative law on questions of political discretion. My objective in this Part, therefore, is to say something about our administrative law by examining the nature of administrative power. I am interested in whether nonenforcement of statutory procedures is a decision of the president or a decision of regulated parties. The relationship between public law and executive power is a central concern within the legal thought of German jurist Carl Schmitt and, on the American scene, Adrian Vemeule’s interpretation of Schmitt’s influence on administrative law. Vermeule’s use of Schmitt’s thought concerning the use of federal emergency powers presents an opportunity to analyze the degree to which administrative power is centralized within a single chief executive.

Vermeule’s thinking about presidential power during emergencies is relevant to discerning the degree to which our administrative law is dependent upon the political discretion of the president. Vermeule hypothesizes that post 9/11 lower courts, in administrative law matters, will be more deferential to the administration thus showing presidents can more lawfully exercise discretion during times of emergency. This would suppose that presidents have substantial control over the administrative law agenda. Using novel data combined with quantitative methods, I find no evidence to support Vermeule’s hypothesis. I then explore the implications of this finding for Vermeule’s broader theories about the American system of administrative law. I draw on the empirical political science literature concerning political power, interest groups, delegation and oversight to argue that our administrative law achieves legal formalism without succumbing to indeterminacy in the ways predicted by Schmitt.

This Part proceeds as follows: first, I analyze what Vermeule means in describing U.S. administrative law as “Schmittian;” second, I empirically test a specific hypothesis suggested by Vermeule predicting that lower court (sub-Supreme Court) judges will be more deferential to the administration on national security matters after 9/11 on emergency grounds. I contribute to the legal literature by collecting a novel set of data limited to judicial review of national security claims by the executive branch and use a logistic treatment effects model to test whether the intervention of the 9/11 emergency causally affected judicial deference in national security cases. Based on the empirical model, 9/11 did not have a statistically significant effect on deference. This indicates the plausibility that, contra Vermeule, our administrative law is not arbitrarily applied in the case of emergency exceptions. I then discuss the implications of my failure to reject the null hypothesis that 9/11 did not significantly change judicial deference, coloring the empirical findings by drawing on quantitative social science literature and recent case studies and data. The inferences drawn by rejecting Vermeule’s theory confirms a number of political features of American administrative law suspected in Part I, including the overdispersion, yet underenforcement, of rules that place interest groups as a central lever of political power in administrative decision-making. The claim is that American administrative law achieves both legality and legitimacy in being overdetermined by interest group politics.

Vermeule’s Schmittian Theory of Executive Power and Discretion

Administrative law scholars have increasingly incorporated German jurist Carl Schmitt’s constitutional critique of liberalism as a lens for understanding administrative law phenomena. For Schmitt, legal liberalism, to the extent it subscribes to a concept of law whereby political decisions are authorized in publicly available rules of law, fails as a theory due to the fact that its executives during states of emergency will make decisions with no formal basis in law and yet no liberal theory can successfully justify these exceptions.61Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, trans. George Schwab ([1922] 1985) at 3. On a granular level, recent Americanists have described agency adjudication as “ruled by a norm of exceptionalism.”62Emily S. Bremer, The Exceptionalism Norm in Administrative Adjudication, 19 Wisc. L. Rev. 1351 (2019).

To say that American administrative law is “Schmittian” is to say that the image of law as rule-bound fails in cases where the executive branch exercises discretion to permissibly violate legal rules during national emergencies. That liberal democracy tolerates or permits rule infractions during emergencies is suggested as evidence that the rule of law, and constitutional liberalism, fails to hold as a governing theory. Adrian Vermeule argues that any “aspiration to extend legality everywhere, so as to eliminate the Schmittian elements of our administrative law, is hopelessly utopian.”63Adrian Vermeule, Our Schmittian Administrative Law, 122 Harv. L. Rev. (2009) at 1097. For Vermeule, the failure of legality is evident when courts rely on emergencies to “increase deference to administrative agencies.”64Id. Such deference is possible because of “open-ended standards” in administrative law that aspire to direct courts to constrain executive action but are substantively ineffective. These feckless legal standards result from “grey holes” in the law.65Id. at 1101. As applied to administrative law, grey holes, like the “arbitrary and capricious” standard for judicial review under the APA, “represent adjustable parameters that courts can and do use to dial up or dial down the intensity of judicial review” in emergency circumstances of war or threats to security.66Id. at 1118. Judicial review becomes “more apparent than real.”67Id.

The relevance of German state thinker Carl Schmitt arises because of the concern that political circumstances, not the legal code itself, best governs how the law is applied.68For Schmitt the rule of law is fanciful because it replaces a “hierarchy of norms” with “a hierarchy of concrete people and instances.” Carl Schmitt, Legality and Legitimacy (1993) at 53. Schmitt’s implication, according to Vermeule, is that “[t]he legal systems of liberal democracies cannot hope to specify either the substantive conditions that will count as an emergency, because emergencies are by their nature unanticipated, or even the procedures that will be used to trigger and allocate emergency powers, because those procedures will themselves be vulnerable to being discarded when an emergency so requires.”69Vermeule, supra note 61 at 1099-1100. Here, Vermeule is paraphrasing Schmitt’s statement in Political Theology that “the precise details of an emergency cannot be anticipated” by legal norms in advance of an emergency. Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, trans. George Schwab, 6 (2005[1934]). While not stated explicitly by Vermeule, Schmitt’s view is that when the chief executive (or administrative state) has the discretion to determine both the existence of an emergency and how to address it, the chief executive remains the only legitimate sovereign.70Schmitt, Political Theology, supra note 67 at 7 (“[the] Sovereign is he who decides on the exception”).

In the context of the public law, Schmitt presents two problems: first, lawmakers cannot craft rules that are sufficient for governing in emergency situations; second, as such, legislators therefore anticipate the need for executive branch discretion (during emergencies or otherwise) by creating “vague standards and escape hatches . . . in the code of legal procedure[.]”71Vermeule, supra note 61 at 1101. For Vermeule, statutes governing administrative action can, at most, specify which official is authorized to act during an emergency but cannot foretell those sets of facts that justify an exception from the general rule.72Id. at 1103 (citing William Scheuerman, Carl Schmitt: The End of Law (1999)). This is why Vermeule concludes that “exceptions” to the general rules that delegate discretion to judges or administrative officials are built into the fabric of administrative law.73Id. at 1104. In practice, Vermeule shows how in a host of judicial decisions interpreting the APA, courts have simply excluded certain agency conduct from the scope of the APA without even analyzing whether the conduct was excepted or excluded under the act, reflecting the existence of “black holes.”74See discussion at id. at 1107-1112. For instance, the APA’s black holes are its general exclusion of uniquely presidential functions and its exceptions for military authorities and functions. And for those administrative law decisions where agency conduct is subject to the APA, Vermeule argues that otherwise stringent standards of review and exceptions are relaxed in the face of emergency, thus reflecting “grey holes.”75Id. at 1123. Note that Vermeule argues that U.S. federal administrative law intentionally embraces “grey holes” in its “ordinary” (as opposed to “emergency”) functioning. See id. at 1134 (“[g]rey holes arise because administrative law in any modern regulatory state cannot get by without adjustable parameters. Such parameters are the lawmakers’ pragmatic response to the sheer size of the administrative state, the heterogeneity of the bodies covered by the APA, the complexity and diversity of the problems that agencies face and of the modes of administrative action, and (related to all these) the lawmakers’ inability and unwillingness to specify in advance legal rules or institutional forms that will create a thick rule of law in all future contingencies, a core Schmittian theme”).

Vermeule’s reasoning also indirectly responds to Jurgen Habermas, the legal and political theorist who has aggressively defended legal liberalism against Schmitt. Habermas argues that liberal democratic law is both formalistic and substantive by involving a distinction between principles and rules.76Jurgen Habermas, Between Facts and Norms (1996), 172. Further, judges resolving public law disputes can avoid merely deferring to the executive when rules are underspecified because they rely on liberal democratic background principles in interpreting and applying statutes.77Id. at 218 (arguing that in adjudication involving government authority, open texture in normative principles does not undermine the public and democratic expectations of adjudication). Vermeule suggests that the idea that “judges would draw upon thick background principles of legality [e.g.,] principles of procedural regularity and fairness” is “a hopeless fantasy.”78Vermeule, supra note 61 at 1105. Vermeule’s view is most strongly stated in the following terms: “it is an inescapable fact that judges applying the adjustable parameters of our administrative law have upheld executive or administrative action on such deferential terms as to make legality a pretense. In such cases, judicial review is itself a kind of legal fiction and the outcome of judicial review is a foregone conclusion – not something that is compatible, even in theory, with the banal liberal-legalist observations that administrative law contains standards and permits deference.”79Id. at 1106.

The Schmittian theory of law during emergencies is that governments sidestep blackletter rules in order to exercise necessary political discretion. This theory would directly explain the phenomena identified in Part I, above, where rules on the books are ignored, and executive orders that largely restate the law are rescinded. Adrian Vermeule theorizes that in the United States, lower federal courts permit such sidestepping.80Id. at 1097-1098.

Vermeule proposes a hypothesis that is testable as an empirical model: “lower courts after 9/11 have applied the adjustable parameters of the APA – ‘arbitrariness,’ ‘reasonableness,’ and so on – in quite deferential ways, creating grey holes in which judicial review of agency action is more apparent than real.”81Id. at 1097. Vermeule made the prediction that after 9/11, lower federal courts, that is sub-Supreme Court, would be more deferential to the federal government in “emergency” cases, particularly ones raising national security concerns. Vermeule argues that “[i]t is logically possible that judges might exercise vigorous review during perceived emergencies, but it is institutionally impossible for them to do so.”82Id. at 1135. Vermeule further explains, at id., “[j]udges defer because they think the executive has better information than they do, and because this informational asymmetry or gap increases during emergencies. Even if the judges are skeptical that the executive’s information really is superior, or if they are skeptical of executive motivations, they are aware of their own fallibility and fear the harms to national security that might arise if they erroneously override executive policies. They also fear the delay and ossification that may arise from judicial review, and that might be especially harmful where time is of the essence”). My goal is to test this hypothesis presented by Vermeule, particularly his claim that “as judicial perception of a threat increases, deference to agencies increases.”83Id. at 1143.

Empirically Assessing Our “Schmittian” Administrative Law: Data and Methods

To assess Vermeule’s claims, I construct a novel set of data on all merits decisions involving exemption 1 of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), which permits the government to withhold information classified “under criteria established by an Executive order to be kept secret in the interest of national defense or foreign policy” and is “in fact properly classified pursuant to such an Executive order.”845 U.S.C. § 552(b)(1). Exemption 1 cases are the most common national security cases subject to review under the APA, which FOIA amended. That FOIA contains exemptions, exclusions and provides a private right of action for unlawful withholdings by the government creates a useful observational scheme for the sorts of issues Vermeule finds relevant in identifying grey holes. Further, the government’s interest in national security secrecy, particularly after 9/11, would well-fit the central expectations of Vermeule’s hypothesis as above-articulated.

A couple of comments on the methodology. First, in coding “deference” I would count any partial summary judgment to the government or partial reversals on appeal that gave appellant some relief as government losses (“0”), else they were government wins (“1”). Given Vermeule’s expectations, it makes little sense to expect that judicial threat perception would be addressed by only partially deferring to the government. In other words, partial deference is a loss for the government during an emergency. Second, if national security was at issue but the case was decided against the government on threshold questions like whether in camera review was necessary or affidavits were sufficient, I counted those decisions as a government loss. In other words, I coded ‘deference’ in such a way as to create a presumption against the government because I’m trying to avoid any error or bias that measures something other than what Vermeule predicted: federal judges voting deferentially toward the government after an exogenous shock in the form of a terror attack. Furthermore, threshold issues present fertile grounds for deference-leaning judges to craft grey holes particularly if case law on a merits question would restrain more engaged interpretations.

While a substantial portion of the exemption 1 FOIA cases are appealed, a coding scheme where not all district-level data has an appellate-level value could significantly bias any model. A number of features of the data explain how I carefully pared the data by coding only some appellate cases while dropping certain district court decisions to avoid any panel-level effects influencing my model: first, and perhaps unique to the FOIA context, the government did not appeal its district court losses so those cases in the sample never have corresponding appeals; second, because of this phenomenon, when a FOIA plaintiff appeals a district court loss and wins on appeal, the initial government win should be considered a loss (indeed as a matter of law it was in error) and therefore I drop these reversed district court deference decisions from the sample; third, in order to avoid homoskedasticity in the data, I drop appellate affirmances of district court decisions for the government. This coding choice effectively corrects what would otherwise be a problematic hierarchical model in which panel decisions were viewed as independent from district court decisions, which de novo review logically prevents.

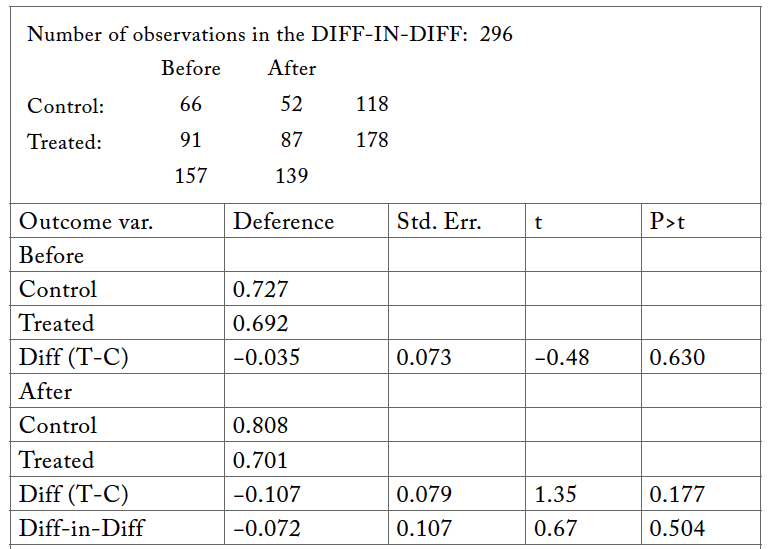

I hand coded each case by date, whether the case occurred before or after September 11, 2001 (the emergency situation), whether the opinion deferred to the federal government on national security (the outcome variable, ‘y’ in my equation), and whether the decision was by a court within the D.C. Circuit to model any biases on deference that might occur due to the fact that most administrative law cases are brought within the D.C. Circuit. This allows me to test a potential sub-hypothesis: whether administrative law expertise leads to less deference in cases of emergency. In the 296 unique exemption 1 cases I studied from 1971 (when the first exemption 1 case appears) to the present, federal courts defer to the administration’s secrecy argument in 72.3% of all cases. And deference by the courts has increased after 9/11 to 74.10%. But that increase is not statistically significant when compared to pre 9/11 deference, for in the 157 exemption 1 cases decided by lower courts prior to 9/11, the courts deferred to the administration in 70.7% of cases. The dependent variable (deference) is binary and my model must aim to measure the effect of 9/11 on the likelihood of judicial deference to government secrecy claims. I also suspect that any effect on deference varies with whether the decision was by a judge or a panel of judges within the D.C. Circuit given their unique expertise in administrative law matters. I discuss my modeling choices and their interpretation in the next section.

Results and Discussion

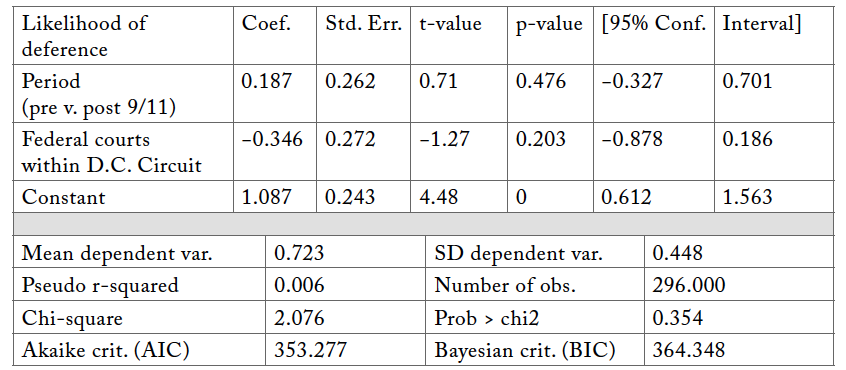

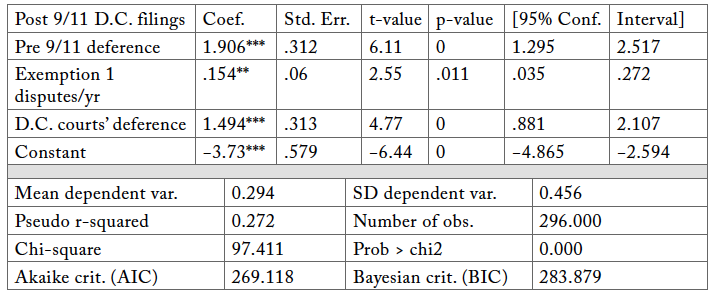

Given deference is a binary (1 or 0 event) dependent variable, I start with a logistic regression model which predicts the likelihood ratio (log-odds) of the dependent variable occurring (in this case, deference) given each unit increase or occurrence in the independent variables. The results are shown in Table 1. Neither of the log odds of the coefficient estimates (increased likelihood of deference post 9/11 but decreased likelihood of deference by D.C. federal courts) reveal a statistically significant (p<.05) relationship with deference so we would fail to reject the null hypothesis that there is no association between the 9/11 attack and deference to national security secrecy by the executive branch.85Note also that a difference of means test from pre (.707) v. post (.741) 9/11 reveals an insignificant difference of .034.

Table 1. Logistic Regression Model: Effects of 9/11 on Judicial Deference to the Executive

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

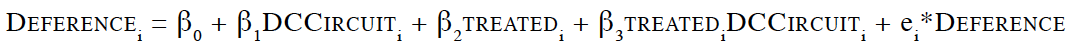

Vermeule’s claim that our legal system cannot specify the substantive conditions that will count as an emergency or the procedures for allocating emergency powers means that emergencies like 9/11 function as exogenous shocks to our legal institutions, thus providing a quasi-experimental condition for making causal inferences about the effects of emergencies on our legal institutions. I conceive of the event of the 9/11 attack as a treatment applied to the sample of judges deciding exemption 1 cases on 9/11 and thereafter. Because case assignments to district court judges or panel selection for appellate judges is random (or assumed random), the parameter error (standard deviation of the sample) for judges hearing exemption 1 disputes after 9/11 would be uncorrelated with the likelihood that a given judge defers to the government’s secrecy claims. Further because 9/11 was itself a random event (at least as it affected federal courts) the treatment is exogenous to the sample of judges deciding exemption 1 cases on or after 9/11. The functional form of a treatment effects model is:

and where the model examines the independent effects of the exogenous shock of 9/11 and administrative law expertise among judges, while also measuring the effects of interacting administrative law expertise and 9/11 on deference. Unlike the first probability model, a treatment effects model can measure the unique causal effects of the 9/11 attack on federal courts within the D.C. Circuit by regressing the difference in variation between the D.C. Circuit courts and all other federal courts as a result of exposure to the 9/11 attack. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Treatment Effects Model of 9/11 on D.C. Circuit Deference

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

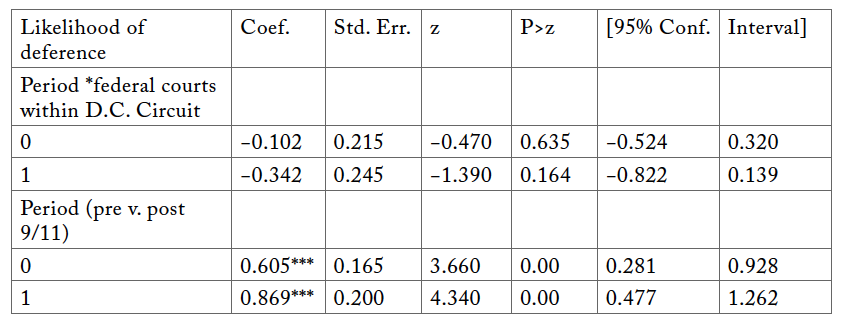

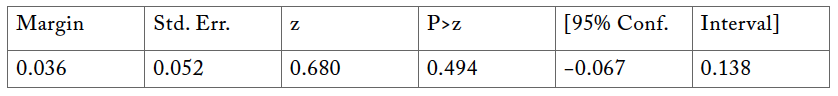

The effects of 9/11 when interacted with the effects of D.C. federal courts on deference are not statistically significant. In looking at the average treatment effect on the entire population of judicial decisions and the specific population of within-D.C. Circuit decisions, in order to measure the difference pre- versus post-treatment, we also cannot reject the null that 9/11 had no effect on deference. The results of these model specifications are displayed in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3. Average Treatment Effect of 9/11 on all Judicial Decisions

Table 4. Average Treatment Effect of 9/11 on Decisions within the D.C. Circuit

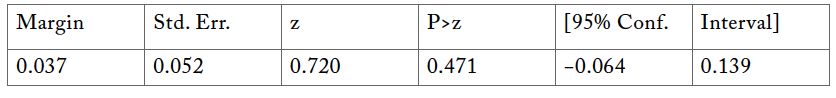

Finally, as a robustness check and because the data contains both expert (within-D.C. Circuit) judges and non-expert judges and where members of (decisions within) each group are not exposed to the treatment (pre-9/11) as well as exposed (post-9/11), I use a causal inference technique called difference-in-differences to model effects of the difference between the treated and non-treated groups as they varied between D.C. federal courts and non-D.C. federal courts in order to model potential causal effects with an additional technique. The results are displayed in Table 5.

Table 5. Difference-in-Differences Model on Treatment Effects on Judges Before v. After 9/11

R-square: 0.01

* Means and Standard Errors are estimated by linear regression

** Inference: *** p<0.1

In the final causal model, we again cannot reject the null hypothesis of 9/11 having no effect on deference. The implication of these results is that lower court federal judges do not unmistakably defer to the executive even when presented with opportunities to fill black or grey holes and where constitutional deference to an administration’s secrecy needs during an emergency would easily outweigh a citizen’s right to access information.

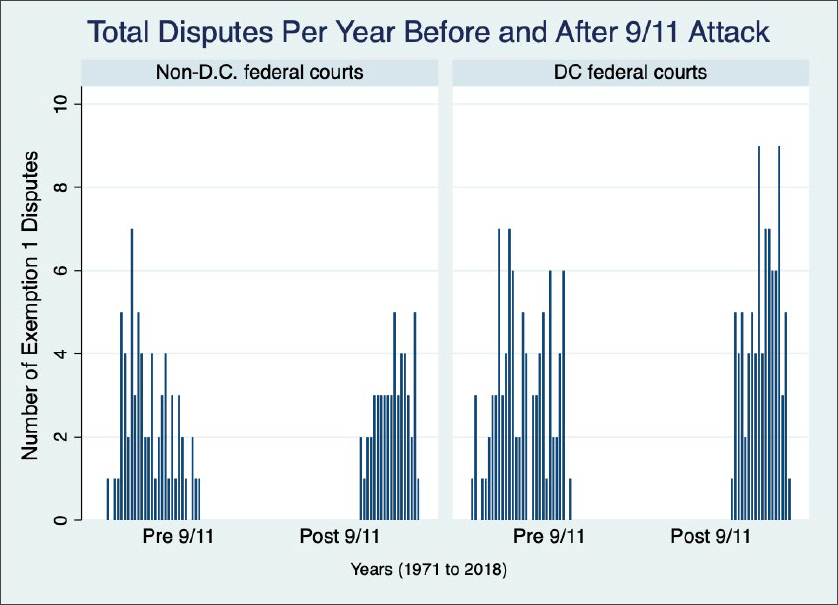

These results indicate that when modeling causal effects of a terrorist attack on federal judges deciding executive branch arguments for an exception from disclosure on national security grounds, judges do not flex their discretion to rely on broad standards in the law as justifications to defer more substantially to the government. While the empirical results could be interpreted to support a number of theories, there are two clear implications of the results. First, that there were no statistically significant differences in deference before versus after the 9/11 emergency means that legal rules were applied consistently throughout. This means that even if judges ratchet up grey holes in order to achieve a preferred policy outcome, they do so independent of the presence of an emergency. Importantly, if motivated reasoning by public law judges is a feature of liberal legal institutions in the normal case and the exception, alike, then states of emergency would not predict jurisprudential change. Second, the data reflects that 9/11 did not alter the statistically observable differences in deference between courts within the D.C. Circuit and other federal courts. This finding supports a number of further claims, which I deduce from Figure 1, which visually models the data.

Figure 1. Total Disputes per Year Before and After 9/11 Attack

Figure 1 illustrates that prior to 9/11, the number of exemption 1 filings per year never exceeded around seven per year in either the D.C. federal courts or the non-D.C. federal courts. But after 9/11, the exemption 1 filings in D.C. federal courts increased (reaching as high as nine per year) while the number of exemption 1 filings outside of D.C. courts decreased (to a high of around five). Even without graphically representing deference, the likelihood that disputes were filed in the D.C. federal courts after 9/11 appears potentially significant. Indeed, there was a 29% relative decrease in non-D.C. Circuit exemption 1 filings after 9/11.

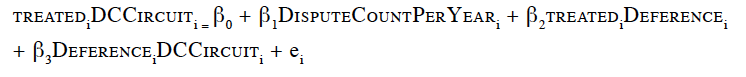

Hypothesizing a change in causal direction: Do strategic litigants shape deference outcomes?

While the statistical evidence supports failing to reject the hypothesis that 9/11 did not affect deference, the parameter measures may be relevant for rethinking causal direction. Rather than Vermeule’s hypothesis, viz., that courts ignore legal rules to increase deference after an emergency, the data suggests the possibility that as the number of judicial decisions (both deferring and not deferring) increases in both D.C.-based and non-D.C. based federal courts, petitioners (those suing the government) may view D.C. courts as more favorable and strategically decide that the likelihood of accessing otherwise secret documents after 9/11 is higher in those courts. In a regression-based means difference test we reject the hypothesis that there is no difference between filing in D.C.-based federal courts and other courts given likelihood of deference prior to 9/11.86This is a difference of means test (t-test) by deference of the D.C. federal courts variable when treatment occurs versus non-D.C.-based federal courts.

I thus propose the following model (simply refactoring the variables from the Vermeule-informed model and changing the proposed causal direction):87This model is simply a transformation of , where I move interaction of treatment (sample of disputes exposed to 9/11 attack) with D.C.-based federal courts (β3) to the dependent variable; move likelihood of deference (y’) to independent variable parameters and interact with treated population (β2); drop new (y) variable (D.C. federal courts) from the independent variable coefficients and have it factor with the error terms; construct a new variable without adding new data that is a count variable of the number of exemption 1 disputes per year; and form a new interaction variable between deference and D.C.-based courts (β3).

In order to run a model with these parameters that are interactions of original model variables, I create new variables representing these products so that we can think of the parameters as influencing the likelihood of future petitions by plaintiffs. The outcome variable is the product of two prior variables: whether a decision was before or after 9/11 (treatment) by whether the decision was in a D.C.-based federal court. This product is labeled “Post 9/11 D.C. filings” as it tracks the likelihood of treatment. The key independent variables are first, a product of government deference and the binary variable indicating before or after 9/11, which given 65% of its observations are null, I’ve labeled “Pre 9/11 deference;” second, a count variable of exemption 1 disputes per year; and third, the product of deference and the variable identifying disputes in the D.C. federal courts, which I’ve labeled “D.C. courts’ deference.” Given the goal is a model that can predict the likelihood that cases will be pursued in the D.C. federal courts after 9/11 (i.e., the likelihood or odds the value of the binary variable is ‘1’), we can use the logistic regression model form from Table 1. The transformed model is shown in Table 4.

Table 6. Logistic Regression Model on Effects of Prior Judicial Deference on Likelihood of Filing in D.C. federal courts

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

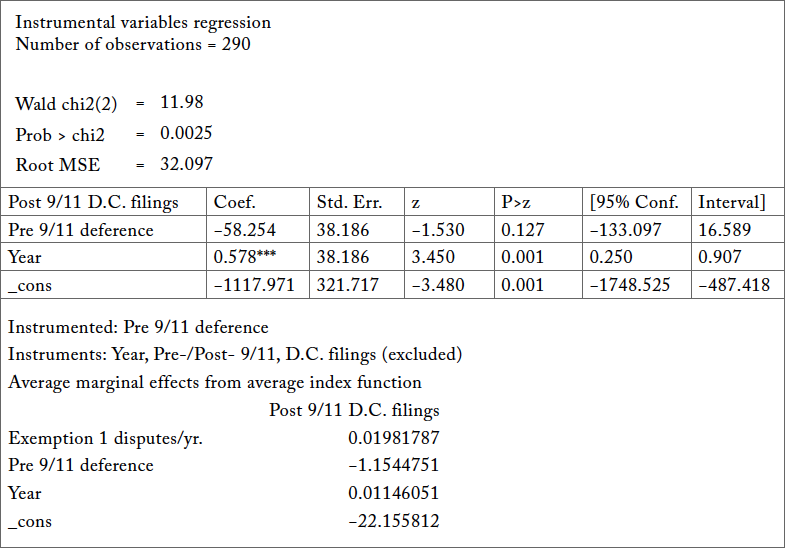

The results show that by transforming the original model by creating new variables out of the same data, the parameter estimates affect the outcome variable with a high degree of statistical significance. In transforming the estimates into odds ratios, we see that the likelihood of exemption 1 filings occurring in the D.C. courts is increased by all the independent variables at a statistically significant level. However, because the new variables may be biased by the increase of null observations (Pre-9/11 multiplied by a deferential opinion is ‘0’), I need a model design as a robustness check where I can remove the potential biasing effects of the treatment and the D.C. courts (now outcome variables) in the parameters. In other words, a potentially debiased model will examine the effects of deference as it varies over the number of disputes on the likelihood that a case is filed after 9/11 in a D.C.-based federal court. Because I predict that prior deference by courts is endogenous to the decision by a petitioner to choose the less deferential D.C.-based federal courts and because deference is a binary (indicator) variable, and further predict that the total number of prior exemption 1 cases will only affect forum choice after 9/11 through deference (and not simply as a result of time passing (e.g. ‘Year’)), I use an instrumental variable design that is appropriate for endogenous indicators. The results are displayed in Table 7, where I exclude from instrumentation the 9/11 effects and D.C. filings (the outcome variable) to ensure an unbiased relationship.88The command I rely on is a program called sspecialreg developed by Christopher Baum and his colleagues. See e.g., https://www.stata.com/meeting/sandiego12/materials/sd12_baum.pdf.

Table 7. Logistic Instrumental Variable Model on Effects of Prior Judicial Deference on Likelihood of Filing in D.C. federal courts

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

The relevant values are the average marginal effects coefficients and since the number of exemption 1 disputes affects the likelihood of a post 9/11 D.C.-based federal court filing only through prior deference (endogenous and already assumed to be correlated with the outcome variable), the key is whether the exogenous regressor, “Year,” is statistically significant in order to evaluate the marginal effects of the increase in exemption 1 disputes as they influence deference. Here, we see a statistically significant relationship and positive marginal effects of exemption 1 disputes on the likelihood of a post 9/11 D.C.-based federal court filing. This confirms the statistical validity of the causal relationships observed in model 6 while factoring out the outcome factors to avoid potential bias concerns.

These empirical results present a strong counter-hypothesis to Vermeule’s. While further empirical investigation is justified by the results, the results of the models identified above provides strong support for the following predictions:

First, the theory of power underlying our administrative law is not focused on the chief executive as sovereign decider but instead the locus of power is found in interest groups who engage in strategic agenda-setting behavior. Administrative law disputes arise due to the legislative empowerment of regulated parties and their organized interests with judicial review rights which ripen through agency petitions. Those interests pursue their claims strategically, which is to say, they consider the past behavior of legislators and judges in making predictions for selecting which issues in which forums to pursue. Strategic choice by litigants depends upon a range of statutory options, for if rules or procedures regulating government action were limited in scope, we would fail to see the evidence of strategic litigation we observed in Model 6. Our administrative law, rather than maintaining holes or gaps in the rules, can be characterized by an overdispersion of legal rules and procedures. That is to say, no one regulatory dispute is resolved by reliance on the totality of germane rules and will always be rule-underinclusive.

Second, because of overdispersion in administrative rules and remedies (procedures), interest groups engage in agenda setting: selecting which procedures to present to courts, which limits the range of legal issues to be resolved by the courts. The role of interest groups, then, has a constraining effect on judicial discretion through agenda control. Thus, interest groups maintain substantial administrative-political power by determining the questions presented before and the relevant legal rules to be decided by judicial decision makers.

Third, because interest groups play a crucial role in setting the administrative law agenda, the fact that interest groups are strategic in seeking judicial relief (i.e., filing in district court within the D.C. Circuit versus a circuit with less regulatory expertise) in addition to pulling the fire-alarms that trigger congressional monitoring of the bureaucracy means that congressional oversight, in addition to judicial monitoring, is an avenue through which rules of law remediate administrative infractions. Importantly, the fact that the administrative law agenda is set by interest groups also means that those same rules on the books which are overdispersed are also underenforced, for interest groups may simply never raise certain procedural arguments.

Fourth, our administrative law anticipates and resolves the exception because it creates the agenda setting conditions whereby regulated parties can pull congressional oversight fire alarms whenever judicial remedies are unavailing (and vice-versa). Further, the competing monitoring of our administrative law from both the courts and Congress permits agency infractions to be evaluated in two senses of legal validity: formal, or technical, validity of rules and consequential, or justification-based, validity of rules. In our system, legality is maintained because overseers from Congress and the courts exercise discretion to enforce against rule infractions based upon public policy justifications. Hence the rule of law does not depend upon the ability to anticipate emergency situations and provide rules that cover the exception but instead thrives when legal decision makers have the flexibility to enforce rules strictly as well as on the basis of public policy and where legislative nullification attends to failing to foresee the consequences of a given rule infraction or providing a legal justification on policy grounds that drifts from the policy preferences of Congress or the president. As such, and because anticipating consequences is subsumed under the rules which structure our administrative law, rule consequentialism forces democratic accountability when agencies make predictions about which policy choices will lead to political oversight where congressional and presidential monitoring to punish infractions establishes governing standards over the bureaucracy. At the same time, agencies and the courts are bound by judicial precedents which are treated by agencies as legally valid statutory and regulatory interpretations.

In the next section, I provide context for these predictions with reference to the political science literature in addition to recent political matters. By analyzing key administrative law cases in the context of pluralist theories of power, I find theoretical support, in addition to the empirical support in Tables 6 and 7 and visible in Figure 1, for these predictions.

The Theory of Regulatory Pluralism

Despite the clear remedies provided under the statutory rights discussed in Part I, regulated parties do not avail themselves. And they must avail themselves because the president, as sovereign, does not exercise unilateral discretion to enforce procedural rules. The sovereign acts upon administrative rules only when subject to a petition by special interests. These findings are suggestive of how we should think about “power” in the administrative state. Administrative power is pluralistic. That is to say, administrative power is not concentrated in political officials but in the regulated parties who set those officials’ decision-making agenda. That regulated parties are not advised by their counsel to secure quasi-due process rights like the requirement that agency jurisdictional statements be publicly noticed in advance, that all investigations must be for a rulemaking purpose, and that all regulatory inquiries of industry members are information collections subject to OMB approval shapes official regulatory decision-making. To change outcomes requires a change in legal strategy.

Vermeule argues that legality fails in the context of the exception because rules cannot anticipate emergency situations. However, the empirical evidence suggests an alternative causal story. Rather than an insufficiency of rules to structure judicial decision-making, our administrative law has an oversupply of procedures; this oversupply of rules governing agency action permits interest groups to use legal challenges as an opportunity to select and apply which rules shape judicial review and test the salience of certain rules in providing a basis for striking down disliked agency decisions; third, that our administrative law is the result of strategic agenda-setting by publicly interested groups signifies how judicial discretion may be effectively cabined consistent with democratic norms. In this section, I highlight the political science literature that colors these inferences while being responsive to Schmitt and I highlight recent matters of bureaucratic infractions as illustrations of how these inferences operate in practice.