Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has asked us to suffer through a medically induced economic coma, with our local businesses mostly shut down and international borders closed to solve a public health emergency. We all want non-essential businesses to get back on their feet as soon as virus containment allows. Each passing month makes it harder for companies to survive and restore jobs and economic opportunity. Millions of people are waiting to be called back, which cannot come soon enough despite the massive stimulus provided in the economy.

The reopening of borders and resumption of global integration is more in question, and rightly so. Global exchange could hasten additional virus outbreaks and second surges. Tourism and foreign business travel will be important economic stimulants to our recovery—particularly the hard-hit sectors of airlines, accommodation, leisure parks, and so on—but only if safety can be secured given the lack of social distance. Others argue that our supply chains need to become more localized, especially for key items like personal protective equipment. Upcoming contracts issued by federal and state governments may contain domestic sourcing clauses, indicating a willingness to pay more for a lesser risk of globalized disruptions.

However we recalibrate global integration, we must protect some of the key advantages America and its economy receive through immigration. As of early June 2020, some policymakers are debating how they might halt vast parts of skilled migration into the country, ranging from not issuing new student visas for foreigners enrolling in our colleges to closing for some time our temporary skilled immigration visa programs like the H-1B. While these proposals are often presented as a thoughtful reaction to the crisis, most of the proponents of these policies expressed similar sentiments well before we ever heard the term “Coronavirus.” Indeed, these restrictions would be a mistake. A better course would be to use this crisis to make our skilled immigration system better and stronger, as it is long overdue for an overhaul.

U.S. innovation and entrepreneurship rely heavily on foreign talent, with immigrants accounting for more than a quarter of our patents and new business start-ups. The end of May saw a vivid example as SpaceX became the first private company to launch astronauts into space; its founder Elon Musk is a South African who came to the U.S. for school by way of Canada. This vital global input is also part of the race against COVID-19. Moderna, one of the companies leading the race for a vaccine, has both an immigrant co-founder and an immigrant CEO. Many scientists working in the pharmaceutical industry come from abroad, and the global scientific community is taking huge steps to cooperate in the vaccine race.

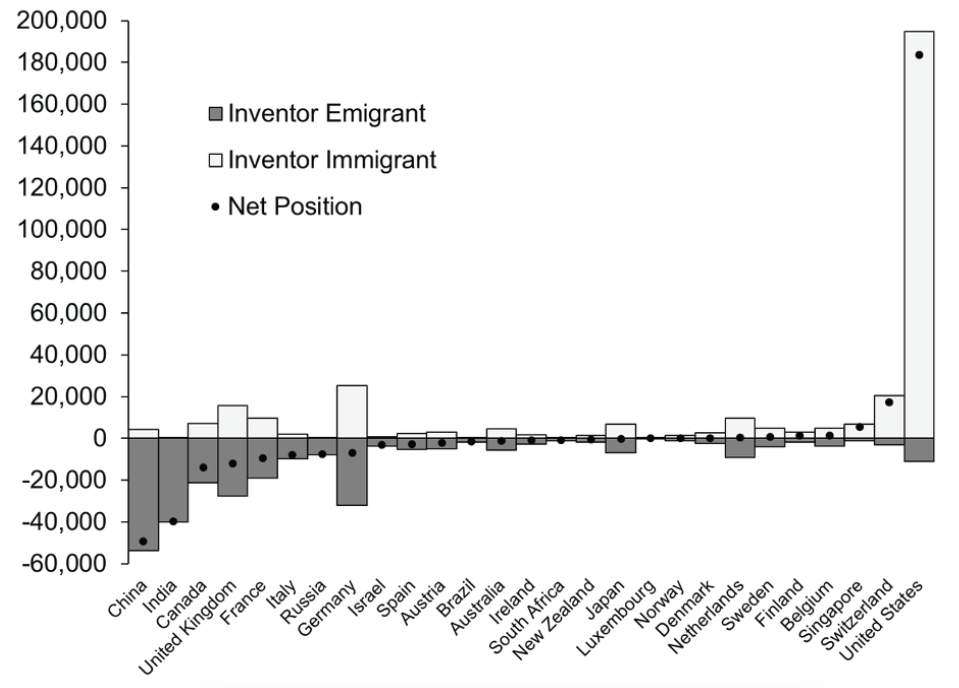

America has historically sat at the center of global talent exchanges, and it would be devastating to lose this special position. The figure below shows the net migration of inventors during the 2000–2010 decade. The United States received an astounding 57% of inventors moving globally! My book, The Gift of Global Talent, catalogs the other lopsided contributions immigrants make to our economy, ranging from winning Nobel Prizes (e.g., four of the Americans awarded the Nobel Prize in 2019 were immigrants) to expanding the college-educated workforce.1William R. Kerr, The Gift of Global Talent: How Migration Shapes Business, Economy & Society, (Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books, 2019), https://www.amazon.com/Gift-Global-Talent-Migration-Business-ebook/dp/B07HQVSHHT.

Figure 1. Migration of inventors, 2000-2010

Sources: Data from Miguelez, Ernest and Carsten Fink. 2013. “Measuring the International Mobility of Inventors: A New Database.” World Intellectual Property Organization Economic Research Working Paper 8.

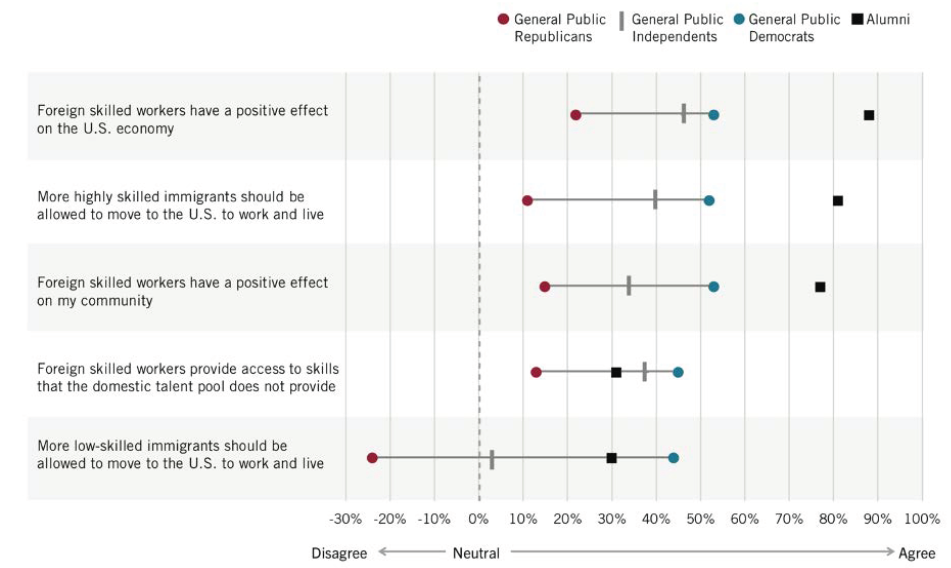

Patents come with digital records, allowing us to make charts like Figure 1. Our research on improving America’s competitiveness also demonstrates the broader degree to which businesses are reliant on skilled immigrants in their workforces. In a survey of Harvard Business School alumni, nearly one in four said that at least 15 percent of their companies’ U.S.-based skilled workforce was foreign-born.2Michael E. Porter, Jan W. Rivkin, Mihir A. Desai, Katherine M. Gehl, William R. Kerr, and Manjari Raman, “A Recovery Squandered: The State of U.S. Competitiveness 2019,” Harvard Business School, 2019, https://www.hbs.edu/competitiveness/Documents/a-recovery-squandered.pdf. Immigrants, they said, were critical for developing better products and services, increasing the quality of innovation, and reaching international customers. Over two-thirds reported that their companies’ operations would be harmed if denied access to skilled foreign workers. In fact, nearly 60 percent already blamed the antiquated U.S. immigration system for causing project delays. Figure 2 below shows the broad net agreement about skilled immigration between business leaders and the general public.3Porter, Rivkin, Desai, Gehl, Kerr, and Raman, “A Recovery Squandered,” 50.

Figure 2. Net agreement for belief statements about immigration

Note: Net-agreement is calculated as the percentage of respondents who agree with statement minus the percentage of respondents who disagree with statement. Calculations exclude responses of “Don’t know” and “Not applicable to me/my company.”

Despite these contributions, there are calls to cease immigration programs like H-1B visas and Optional Practical Training (OPT). Those changes would come at a heavy price for American innovation. Our best companies rely on H-1B workers for hard-to-fill positions. The tech sector, a huge driver of economic growth and creator of American jobs, needs the skills these workers provide to develop their products and invent new technologies. The OPT program, meanwhile, allows us to take advantage of foreign students’ willingness to contribute to our economy after their studies wrap up. International students help fund our educational institutions and academic research, enrich the learning environment for American students, and further the exchange of ideas. To break our promise of opportunity to these students would dampen the enthusiasm of the world’s youth to use and grow their talents here. In turn, it would weaken our economic competitiveness in the future.

Rather than end the programs, we should take the opportunity to make them stronger. The H-1B visa, for example, is allocated through a very crude process. Despite having received about 275,000 applications for 85,000 visas in March 2020 (notably, after COVID-19 became very visible), the U.S. government allocates the visas via two lotteries. This random process does not prioritize the highest-valued uses of a scarce visa supply—a loss for America as a whole. This crudeness can even result in uses of the program that hurt American workers. I have argued for wage ranking each company’s visa applications.4Kerr, “The Gift of Global Talent.”This system would replace the randomized lottery by awarding visas to those who will pay the most for each position. This takes signals from the labor market regarding how much companies were willing to pay for the talent to prioritize visa uses. Whether wage ranking, stricter H-1B minimum wages, visa auctions, or some other sensible measure, now is the time to start putting the visas towards their best uses.

These reforms, along with preserving student visas and the bridging OPT program, are vital for how America will be viewed in the eyes of future students. One study by Takao Kato and Chad Sparber gives a forceful lesson for how much foreign students, especially the best ones, consider future access to U.S. jobs when choosing to come to college in America.5Takao Kato and Chad Sparber, “Quotas and Quality: The Effect of H-1B Restrictions on the Pool of Prospective Undergraduate Students from Abroad,” Review of Economics and Statistics 95, no. 1, (2013): 109-26, https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00245. The researchers analyzed a modest decline in the likelihood that graduating students would be able to acquire H-1B visas in 2004. A prior visa program expansion was due to sunset, and so fewer visas would be available. This resulted in fewer applications by international students for college. This enrollment decline was despite the four or more years expected before graduation even happened, and an H-1B became necessary! Moreover, the choice of students to go elsewhere was especially pronounced among the most qualified candidates. The 2004 event that caused this measurable decline was tiny in comparison to today’s calls to end student visas, stop the OPT program, and halt H-1B entirely.

What this episode uncovers is how much uncertainty can damage skilled immigration. The U.S. immigration system has never been “user friendly” to be sure. The world’s talent was willing to put up with the hurdles for the opportunity to study and work in America. This investment made our country a special place for innovation and invention, per Figure 1, and people are most willing to invest when they feel secure in the future. Hostile rhetoric and anti-immigration policy actions over the past few years have already taken the luster off America for those abroad, causing deep uncertainty about investing in the country. Some graduate education fields like business schools have already witnessed two or three years of consecutive declines in foreign applications, over-and-above any changes in application rates from natives.6 Closing the borders to stop the spread of the pandemic was the right choice; closing them unnecessarily into the future will place America on a new trajectory away from global talent that will be hard (or impossible) to reverse in the future.

Even before COVID-19, other countries were increasingly competing with us to take more market share in the global talent market. For example, America’s share of college-educated migrants is falling relative to other OECD countries.6Kerr, “The Gift of Global Talent.” Innovative programs in other nations to attract these future innovators further threaten our competitive advantage. America, too, must innovate.

One bi-partisan opportunity for policy innovation is an immigrant entrepreneur visa.7Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Immigration Policy Levers for US Innovation and Startups,” in Innovation and Public Policy, ed. Austan Goolsbee and Benjamin Jones, (National Bureau of Economic Research: University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/20-105_aac0d5ae-e6e3-4570-8225-31bcc127f693.pdf. Despite the many case studies of foreign entrepreneurs aiding America, our existing immigration pathways have an unfortunate gap when it comes to aspiring entrepreneurs who are not already wealthy. Thus, while we have programs that facilitate the migration of foreigners who can invest $1.8 million into a U.S. business, we don’t have a secure pathway for a graduating college student who has a strong business idea but little existing wealth. Give the desirability of the jobs created by new businesses – the ultimate free lunch perhaps – countries like Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom have each created their own entrepreneur visa. These programs have strong qualification standards (e.g., the entrepreneur’s background, the economic impact it will achieve, etc.) and sometimes require that the entrepreneur has successfully raised start-up capital from qualified investors. Absent such a program in the U.S., aspiring entrepreneurs either create awkward workarounds (e.g., work nights and weekends on the idea while on an H-1B) or go to another country. In recent years, more than two dozen bills have been introduced in Congress by Democrats and Republicans to remedy this weak spot and received bi-partisan support, and we need to get one of these pushed through and enacted.

When it soon becomes time to fully reopen our borders to immigrants, let us be prepared to reform our immigration system to work better for all stakeholders.8Kerr and Kerr, “Immigration Policy Levers for US Innovation and Startups.” Our Harvard Business School survey showed remarkable consistency across business leaders and the general public for wanting to bolster the employment-based nature of U.S. admissions. While now is not the right time for designing and debating such extensive overhauls, policymakers can use this challenging environment to make some quick wins that provide momentum for when reform is feasible. Implementing a better H-1B visa allocation system and establishing a visa for immigrant entrepreneurs are two possibilities.

Above all, we must educate voters and build support for policies that enhance American innovation and American competitiveness. While blaming foreigners for economic or public health troubles has long been part of the nationalism playbook, economic integration and openness to foreign talent are a stronger path for long-term success as a country.

References

1. William R. Kerr, The Gift of Global Talent: How Migration Shapes Business, Economy & Society, (Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books, 2019), https://www.amazon.com/Gift-Global-Talent-Migration-Business-ebook/dp/B07HQVSHHT.

2. Michael E. Porter, Jan W. Rivkin, Mihir A. Desai, Katherine M. Gehl, William R. Kerr, and Manjari Raman, “A Recovery Squandered: The State of U.S. Competitiveness 2019,” Harvard Business School, 2019, https://www.hbs.edu/competitiveness/Documents/a-recovery-squandered.pdf.

3. Porter, Rivkin, Desai, Gehl, Kerr, and Raman, “A Recovery Squandered,” 50.

4. Kerr, “The Gift of Global Talent.”

5. Takao Kato and Chad Sparber, “Quotas and Quality: The Effect of H-1B Restrictions on the Pool of Prospective Undergraduate Students from Abroad,” Review of Economics and Statistics 95, no. 1, (2013): 109-26, https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00245.

6. Scott Jaschik, “Understanding the Decline in M.B.A. Applications,” Inside Higher Ed, February 4, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2019/02/04/new-data-help-explain-decline-mba-applications.

7. Kerr, “The Gift of Global Talent.”

8. Sari Pekkala Kerr and William R. Kerr, “Immigration Policy Levers for US Innovation and Startups,” in Innovation and Public Policy, ed. Austan Goolsbee and Benjamin Jones, (National Bureau of Economic Research: University of Chicago Press, 2020), https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/20-105_aac0d5ae-e6e3-4570-8225-31bcc127f693.pdf.

9. Kerr and Kerr, “Immigration Policy Levers for US Innovation and Startups.”