The current implementation of NEPA causes paralysis and indecision

The aim of NEPA is to ensure that major Federal actions affecting the environment are informed and well-considered. NEPA is a procedural statute that directly provides no substantive environmental protection. For example, NEPA does not include rules about safe levels of pollutants or water quality that agencies must meet when considering a major federal action. Agencies can proceed with actions that create negative environmental effects as long as they are documented and considered. The goal of the NEPA process is to ensure that agencies confront the likely environmental effects of their decisions and potential alternatives to their action.

The danger with any procedural system is that the procedure can become an end in itself, unmoored from its objectives. That unmooring is what has happened under the current implementation of NEPA, resulting in slow and ineffective Federal decisions across a wide range of issues. The threat of NEPA litigation has created an incentive for Federal agencies and private applicants to produce encyclopedic environmental documents in an effort to become litigation-proof.1 Randy T. Simmons, Ken Sim, and Ryan M. Yonk, Nature Unbound: Bureaucracy Vs. the Environment (Independent Institute, 2016), 94–95. This has led to paralysis, indecision, and high costs as environmental review extends for years and even decades. In addition, the existing implementation has lent itself to weaponization, which has harmed Federal decision making.

There are better ways to protect the environment than requiring agencies to engage in multi-year long reviews before every major action. Effective substantive environmental standards and taxes on environmental externalities have the virtue of protecting the environment directly and without wasteful paperwork and delay. We favor this substantive approach rather than NEPA’s procedural approach. While replacing procedural protections with substantive ones is not on the current docket, we believe improvements to NEPA-implementing procedures are warranted.

Environmental review timeframes are long and growing

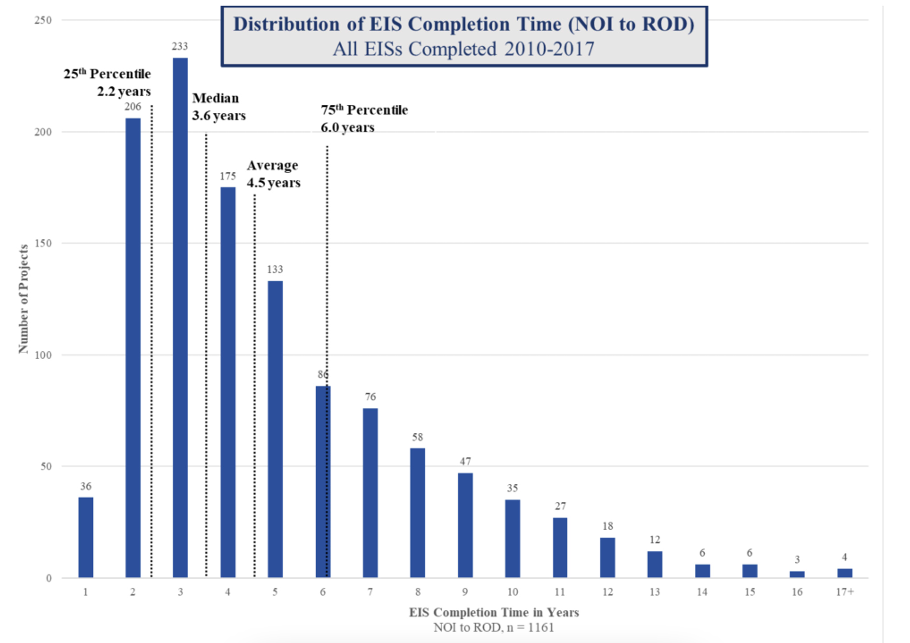

CEQ conducted a review of environmental impact statement (EIS) timelines for EISs completed between 2010 and 2017 and found that the mean completion time from notice of intent to record of decision was 4.5 years.2“Environmental Impact Statement Timelines (2010–2017)” (Council on Environmental Quality, December 14, 2018). The median completion time was 3.6 years. The National Association of Environmental Practitioners (NAEP) finds even longer timelines in its 2018 annual report, with data showing that mean completion time for EISs finalized in 2018 was 4.9 years from notice of intent to availability of final EIS, excluding the additional time to publish the record of decision.3 Charles P. Nicholson, “2018 Annual NEPA Report of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Practice” ( National Association of Environmental Professionals, November 2019), https://naep.memberclicks.net/assets/documents/2019/NEPA_Annual_Report_2018.pdf. These long timelines mask considerable variation. CEQ found 36 EISs that were completed within one year, and 206 of them that were completed within 2 years, as shown in Figure 1. At the other end of the distribution, dozens of EISs took a decade or more to complete.4“Environmental Impact Statement Timelines (2010–2017).”

Figure 1: CEQ Data on EIS Completion Timelines5“Length of Environmental Impact Statements (2013-2017)” (Council on Environmental Quality, July 22, 2019), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/CEQ_EIS_Length_Report_2019-7-22.pdf.

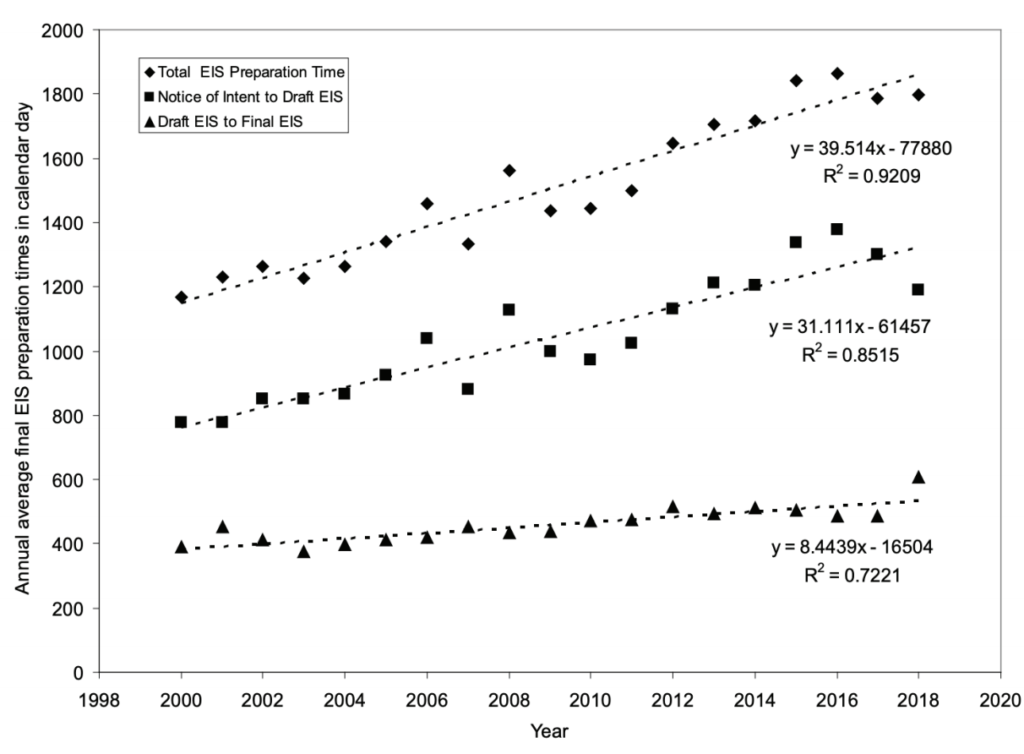

EIS timeframes are not just long, they are getting longer each year. NAEP’s 2018 annual report finds that between 2000 and 2018, EIS preparation time increased by an average of 39.5 days per year.6Nicholson, “2018 Annual NEPA Report of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Practice.” These numbers are supported by other analyses that find similar results. A 2007 paper found that average EIS timelines were growing by 37 days per year,7Piet deWitt and Carole A. deWitt, “How Long Does It Take to Prepare an Environmental Impact Statement?,” Environmental Practice 10, no.4 (December 3, 2008): 164–74. and an updated analysis by the same authors concludes that EIS preparation timelines from 2007 until 2010 were growing by an average of 19.9 days each year.8Piet deWitt and Carole A. deWitt, “Research Articles: Preparation Times for Final Environmental Impact Statements Made Available from 2007 through 2010,” Environmental Practice, 2013, doi:10.1017/s1466046613000033. As Figure 2 shows, the overall timelines are trending upwards.9 Nicholson, “2018 Annual NEPA Report of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Practice.”

Figure 2: NAEP Data on the Growing EIS Preparation Times10Ibid.

The environmental review process can be and has been weaponized

The first major judicial opinion interpreting NEPA, Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Committee v. United States Atomic Energy Commission, begins with a prophecy: “These cases are only the beginning of what promises to become a flood of new litigation.”11 Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Committee v. United States Atomic Energy Commission, 449 F.2d 1109 (U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit 1971). In data on NEPA litigation from 2001 to 2013, CEQ finds there are approximately 115 challenges to NEPA decisions in court per year.12 Council on Environmental Quality, “NEPA Litigation Surveys: 2001-2013,” accessed March 4, 2020, https://ceq.doe.gov/docs/ceq-reports/nepa-litigation-surveys-2001-2013.pdf. These cases add further delay to the NEPA process, and the lawsuits are not generally attributable to poor document quality, because the data show that most of them are won by the government. A recent working paper analyzes this CEQ data and finds that plaintiffs win NEPA cases less than 20 percent of the time.13John Ruple and Kayla Race, “Measuring the NEPA Litigation Burden: A Review of 1,499 Federal Court Cases,” Environmental Law 50, no. 2 (Forthcoming 2020), doi:10.2139/ssrn.3433437.

Litigation is not the norm. Many EIS documents move through the process without unconscionable delays and without drawing a lawsuit. CEQ’s completion time data shows that most EISs are completed within 4 years. One in 4 EISs, however, takes at least 6 years to complete. The long tail of the distribution extends far to the right, with four EISs taking more than 17 years to complete, and because the CEQ data includes only completed EISs, the data necessarily exclude EISs that have been delayed so long that they have yet to conclude.14 “Environmental Impact Statement Timelines (2010–2017).”

Yet neither the long timeframes of EISs or the volume of NEPA cases yields a complete picture of why the current implementation of NEPA is so problematic. Instead, the most damaging aspect of today’s NEPA rules is the potential for strategic use of the process against targeted projects, which is colloquially known as weaponization.

Sometimes, the goal of weaponization is motivating a move upwards in the level of review, such as from an environmental assessment to an EIS. One case discussed in a congressional hearing involved subsurface drilling. The company involved testified that the Bureau of Land Management was ready to apply a categorical exclusion to the project. After environmental organizations levied a suit against the agency, however, the Bureau changed course and demanded an environmental assessment.15 Melissa L. Hamsher, “The Weaponization of the National Environmental Policy Act and the Implications of Environmental Lawfare,” (Oversight Hearing: Committee on Natural Resources, Washington DC, April 25, 2018), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG115hhrg29883/html/CHRG-115hhrg29883.htm

Another example of weaponization is the case of the Keystone XL pipeline, which became controversial for symbolic reasons, according to President Obama.16Barack Obama, “Statement by the President on the Keystone XL Pipeline,” November 6, 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/thepress-office/2015/11/06/statement-president-keystone-xl-pipeline.pdf. The State Department spent seven years analyzing the likely emissions related to the pipeline’s use and concluded that the pipeline would reduce global greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental groups showed that using different assumptions the pipeline would increase emissions. The State Department then reversed itself, choosing not to move forward because the pipeline had the potential to appear as if the pipeline would increase greenhouse gas emissions.17James W. Coleman, “Fixing the National Environmental Policy Act,” (Committee on Natural Resources Hearing: The Weaponization of the National Environmental Policy Act and the Implications of Environmental Lawfare, Washington DC, April 25, 2018), https://docs.house.gov/meetings/II/II00/20180425/108215/HHRG-115-II00-TTF-ColemanJ-20180425.PDF.

Under a new administration, the State Department once again favored construction of Keystone XL. The pipeline was sued again under NEPA and enjoined, and President Trump personally issued a permit, mooting the issue. The final supplemental EIS was published in December 2019. Weaponization of the NEPA process led to a decade of delay for essentially symbolic objections to the pipeline.

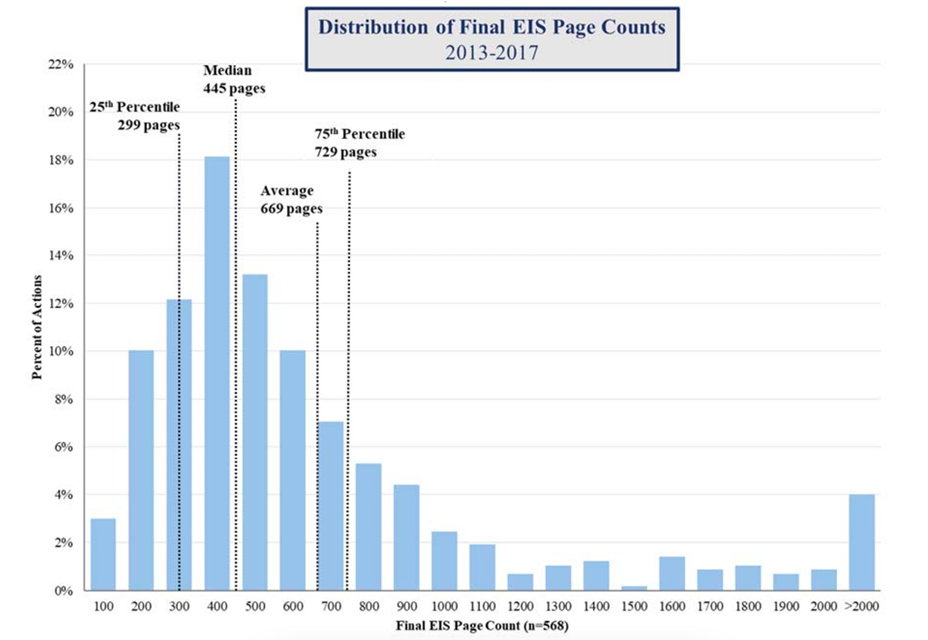

Evidence of the weaponization of NEPA is also found in the length of EIS documents. Despite a requirement that EISs normally be less than 150 pages and statements for unusually complex environmental actions be less than 300 pages, the documents regularly balloon to much more than that. A 2019 review by the CEQ found that the average final EIS is 669 pages.18“Length of Environmental Impact Statements (2013-2017).” These numbers do not include appendices to an EIS. The average appendices found by the CEQ is 1,037 pages.19Ibid.

As with the timelines, the average is not as informative as the full range of EIS lengths. Four percent of EISs exceed 2,000 pages, as Figure 3 shows.20Ibid. Lengthy documents occur for multiple reasons, as CEQ’s report notes. Involving more agencies often means that an EIS becomes longer as there are more contributors. Researchers have also identified the effort to prevent lawsuits as a primary reason for long environmental documents. Because leaving any potential environmental issue or alternative to the proposed action unconsidered in the EIS can give cause for a lawsuit, agencies seek to litigation-proof their EISs by including everything.21Ibid.; Simmons, Sim, and Yonk, Nature Unbound: Bureaucracy Vs. the Environment, 94–95; J. Matthew Haws, “Analysis Paralysis: Rethinking the Court’s Role in Evaluating EIS Reasonable Alternatives,” University of Illinois Law Review, 2012, 537–76. Failing to prevent a lawsuit carries cost increases and may even make the review documents themselves less useful to agencies carrying out the actions by cluttering them with unlikely scenarios.22 Simmons, Sim, and Yonk, Nature Unbound: Bureaucracy Vs. the Environment, 83–86, 94–96.

Figure 3: CEQ Data and Graphic on EIS Page Lengths23 “Length of Environmental Impact Statements (2013-2017).”

Ineffective Federal decision-making is bad for the environment

The propensity of the NEPA process to delay projects for years at a time creates environmental costs. The status quo is exempted from environmental review, and federal actions that may improve environmental quality over the status quo can be delayed or prevented by the review process.24 Richard A. Epstein, “The Many Sins Of NEPA,” Texas A&M Law Review 6, no. 1 (2018): 1–28

There are numerous examples of the NEPA process imposing delays on projects that could result in environmental benefits. New York City’s congestion pricing scheme, which could generate significant reductions in air pollution, is currently being delayed by uncertainty over NEPA paperwork.25 Dana Rubinstein, “Why Congestion Pricing Might Be Delayed,” Politico PRO, February 18, 2020, https://politi.co/2vGWl3F. Vineyard Wind, a $2.8 billion, 800-megawatt offshore wind energy project is also facing delays from environmental review.26Colin A. Young, “Federal Review Will Further Delay Vineyard Wind,” WBUR, August 9, 2019, https://www.wbur.org/earthwhile/2019/08/09/vineyard-wind-project-delayed. Other commenters have pointed out generally that the rollout of renewable energy development is stymied by NEPA.27Trevor Salter, “NEPA and Renewable Energy: Realizing the Most Environmental Benefit in the Quickest Time,” Environmental Law and Policy Journal 34, no. 2 (2011): 173–88; Michael B. Gerrard, “Legal Pathways for a Massive Increase in Utility-Scale Renewable Generation Capacity,” Environmental Law Reporter 47 (2017), https://climate.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/pics/homePage/Legal-Pathwaysfor-a-Massive-Increase-in-Utility-Scale-Renewable-Generation-Capacity.pdf.

Abigail Kimbell from the Forest Service has testified that NEPA litigation drains its resources and delays restoration projects:

It is also important to note that each time we go through the appeal process or the courts, much of our limited resources are employed to defend the decisions we feel are crucial to restoring ecosystems and addressing forest health concerns. There is no special budget for litigation, no special team of resource specialists. The same resource teams that are charged with completing required analysis on current and future projects must delay that work to prepare extensive administrative records for legal challenges.”28Abigail R. Kimbell, “Testimony,” (Committee on Resources The Task Force on Improving NEPA Concerning The Role of NEPA in the States of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana and Alaska, Spokane, Washington, April 23, 2005), https://www.fs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/legacy_files/media/types/testimony/042305.pdf.

Kimbell also testified that delays in restoration projects “leave forests susceptible to insect and disease and predispose ecosystems to unwanted wildfire.”29Ibid. These environmental hazards are ignored because NEPA privileges the status quo.

Environmental scholar and practitioner Laura Watt testified that the National Park Service applied NEPA requirements inconsistently, “apparently on the basis of whether it likes a particular program or project.”30Laura A. Watt, “Testimony: The Weaponization of the National Environmental Policy Act and the Implications of Environmental Lawfare,” (Committee on Natural Resources Hearing: The Weaponization of the National Environmental Policy Act and the Implications of Environmental Lawfare, Washington DC, April 25, 2018), https://docs.house.gov/meetings/II/II00/20180425/108215/HHRG-115-II00-TTFWattL-20180425.pdf. In her judgment, removal of ranching from the Point Reyes National Seashore undermined centuries of active management of the landscape since before the arrival of Europeans. This was a significant land use change, yet NPS did not subject it to NEPA review. The removal of ranching left some areas within PRNS at greater risk of wildfire and resulted in “unmanaged pastures being taken over by invasive brush and weeds.”31 Ibid.

Ineffective Federal decision making is bad for the economy

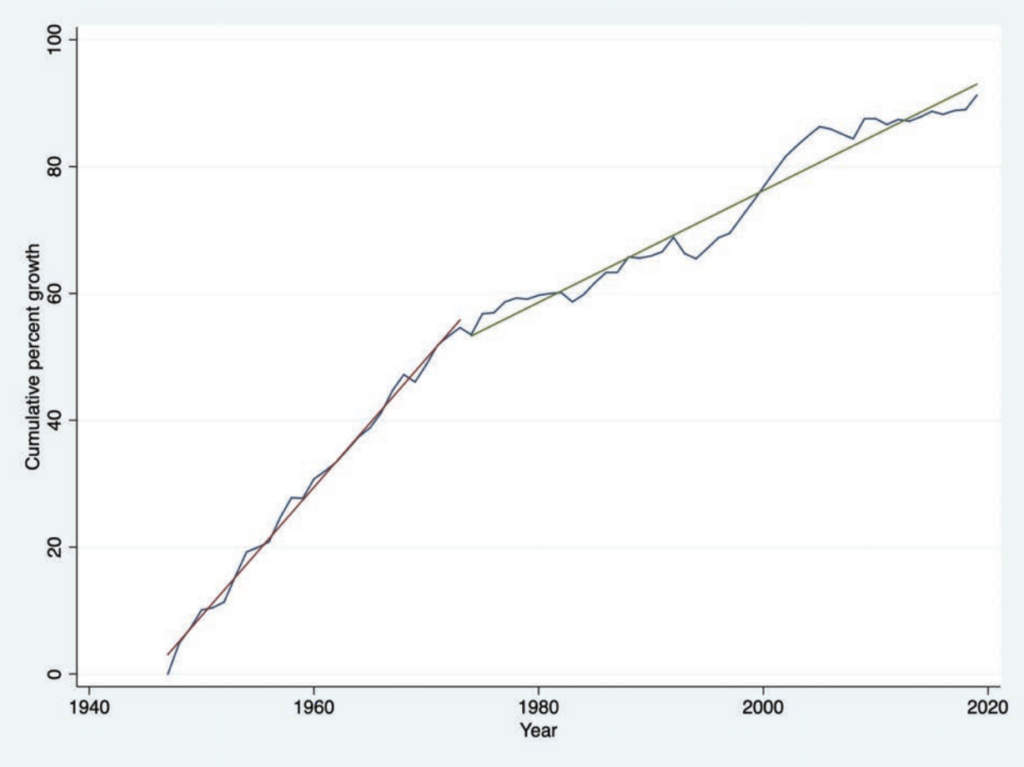

The United States economy has been stagnating since the early 1970s. Economist Tyler Cowen calls the period since 1973 the Great Stagnation.32 Tyler Cowen, The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All the Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (eventually) Feel Better (Dutton Adult, 2011). Growth in total factor productivity, the broadest measure of economic progress, fell sharply around 1973, as Figure 4 shows.

Figure 4: Growth in total factor productivity since 194733 John Fernald, “Total Factor Productivity,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, accessed March 8, 2020, https://www.frbsf.org/economicresearch/indicators-data/total-factor-productivity-tfp/.

We do not blame this economic stagnation entirely on NEPA, which came into effect as a statute on January 1, 1970 and was implemented in regulation in the ensuing years. Numerous other regulatory changes came into effect in this period, and probably not all the causes of economic stagnation are regulatory. Nevertheless, four-and-a-half decades of economic stagnation underscore the need for bold action to improve economy-wide productivity.

A major element of any such action to improve productivity is revitalizing American infrastructure. Yet any effort to modernize our infrastructure runs headlong into delays imposed by compliance with NEPA. With an average completion time of six-and-a-half years, the EIS timelines are significantly longer for Department of Transportation projects than many other agencies.34“Environmental Impact Statement Timelines (2010–2017).” This means that even if Congress unanimously agreed today to develop a nationwide high-speed rail network, the first shovelful of dirt would not be expected to be moved until late 2026.

NEPA’s long timelines also contribute to ineffective macroeconomic policy implementation. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) was passed to provide economic stimulus in the midst of the Great Recession which started in 2008. However, fully implementing the stimulus in the ARRA would have required 192,707 NEPA reviews including 841 EISs.35Mark C. Rutzick, “A Long and Winding Road: How the National Environmental Policy Act Has Become the Most Expensive and Least Effective Environmental Law in the History of the United States, and How to Fix It,” October 16, 2018, https://regproject.org/wp-content/uploads/RTP-Energy-Environment-Working-Group-Paper-National-Environmental-Policy-Act.pdf; “The Eleventh and Final Report on the National Environmental Policy Act Status and Progress for American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 Activities and Projects” (Council on Environmental Quality), accessed March 3, 2020, https://ceq.doe.gov/docs/ceq-reports/nov2011/CEQ_ARRA_NEPA_Report_Nov_2011.pdf. Since the point of stimulus is to rapidly inject Federal money into the economy, the NEPA process defeated the purpose of the ARRA. One writer quipped, “there are no longer any ‘shovel-ready projects’ within the federal enclave.”36 Rutzick, “A Long and Winding Road: How the National Environmental Policy Act Has Become the Most Expensive and Least Effective Environmental Law in the History of the United States, and How to Fix It.”

Ineffective Federal decision making is bad for America’s place in the world

Stalled Federal action on transportation infrastructure compares unfavorably with decisions taken in China. Since 2008, China has developed 25,000 km of high-speed rail.37Martha Lawrence, Richard Bullock, and Ziming Liu, “China’s High-Speed Rail Development,” 2019, doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1425-9. Despite bipartisan support for ambitious infrastructure programs, the United States seems incapable of producing similar results. While we spend years on environmental paperwork, our biggest geopolitical counterweight has taken decisive action to produce meaningful economic investments.

This contrast is especially damaging because China and the United States represent alternative political models—other governments, observing China’s seemingly effective authoritarianism and our slower, less decisive democracy, may decide to align with the autocrats to the detriment of US influence in the world. It is vital for America’s continued global leadership that we improve the speed and effectiveness of government decision making

Reforms to NEPA-implementing regulations can improve the effectiveness of Federal decision-making

The need to improve the NEPA process has been identified by multiple administrations and Congresses over the last 50 years.38 Jonathan C. Wood, “Speeding up Environmental Reviews Is Good for the Economy and the Environment,” The Hill, February 6, 2020, https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/481513-speeding-up-environmental-reviews-is-good-for-the-economy-and-the.

President Clinton’s CEQ concluded in a 1997 report that “…the exercise can be one of producing a document to no specific end. But NEPA is supposed to be about good decision-making—not endless documentation.”39“The National Environmental Policy Act: A Study of Its Effectiveness After Twenty-Five Years” (Council on Environmental Quality, January 1997), https://ceq.doe.gov/docs/ceq-publications/nepa25fn.pdf. President Bush issued EO 13274, Environmental Stewardship and Transportation Infrastructure Project Reviews, in 2002. Congress passed the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act in 2005. President Obama issued EO 13604, Improving Performance of Federal Permitting and Review of Infrastructure Projects in 2012. Also in 2012, Congress passed the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act. Obama also issued a Presidential Memorandum in 2013, Expediting Review of Pipeline Projects from Cushing, Oklahoma, to Port Arthur, Texas, and Other Domestic Pipeline Infrastructure Projects, to attempt to expedite review of pipeline projects.40 Coleman, “Fixing the National Environmental Policy Act.” Most recently, Congress passed the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act in 2015, which created a pilot program for states to administer their own environmental processes instead of NEPA if they met certain qualifications.41“A Summary of Highway Provisions – FAST Act | Federal Highway Administration,” accessed March 4, 2020, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/fastact/summary.cfm.

The specifics vary between each of these reform efforts, but the trend is unmistakable. Every administration since 1993 has pursued efforts to streamline and improve the NEPA process. Fast-tracking infrastructure projects like roads and pipelines have featured prominently in each president’s strategy.

Because of the many problems with the current NEPA implementation we have identified, we welcome the Administration’s initiative in reforming the NEPA process. Careful reviews have become an end in themselves instead of a means targeted at protecting the environment.42 Paul J. Culhane, “NEPA’s Impacts on Federal Agencies, Anticipated and Unanticipated,” Environmental Law 20, no. 3 (1990): 681–702 In place of such paralysis, a review process that encourages action will better promote environmental health than the current NEPA processes.

Suggestions for improvement of the proposed rule

§ 1501.4 Categorical exclusions

CEQ invites comment on whether there are any other aspects of categorical exclusions (CEs) that it should address in its regulations. We support the idea raised for discussion in the NPRM of establishing government-wide CEs to address routine administrative activities. This measure would improve the efficiency of the entire executive branch.

We would also suggest that agencies should regularly and systematically evaluate their corpus of environmental assessments to determine whether there could be efficiency gains from establishing new CEs. As noted in the NPRM, CEQ estimates that Federal agencies prepare approximately 10,000 EAs each year. If a portion of these EAs could be obviated through additional CEs, that would create recurring efficiency gains that would continue long into the future.

Suggested new § 1501.4(c): No more than 12 months after [PUBLICATION DATE OF FINAL RULE], and no less frequently than every 5 years thereafter, each agency shall:

(1) Review the environmental assessments it has prepared over the previous 5 years or since the last review;

(2) Submit to the Council a memorandum detailing the number and categories of actions that resulted in environmental assessments; and

(3) Consult with the Council as to whether it could reap efficiency gains by establishing new categorical exclusions.

§ 1501.10 Time limits

CEQ invites comment on § 1501.10’s presumptive timeframes and whether the regulations should specify shorter timeframes. We support the idea of establishing presumptive time limits for the completion of EAs and EISs, and we believe 1-year and 2-year presumptive time limits are appropriate. However, in the event that an EIS follows an EA, we believe the time limit for the EIS can be shortened to reflect the work already done in the EA to identify and evaluate the potential environmental effects of the action.

CEQ’s proposed § 1501.10(b)(2):

(2) Environmental impact statements within 2 years unless a senior agency official of the lead agency approves a longer period in writing and establishes a new time limit. Two years is measured from the date of the issuance of the notice of intent to the date a record of decision is signed.

Our suggestion (amend subparagraph 2 and add subparagraph 3):

(2) Environmental impact statements preceded by an environmental assessment within 1 year unless a senior agency official of the lead agency approves a longer period in writing and establishes a new time limit. One year is measured from the date of the issuance of the notice of intent to the date a record of decision is signed.

(3) Environmental impact statements not preceded by an environmental assessment within 2 years unless a senior agency official of the lead agency approves a longer period in writing and establishes a new time limit. Two years is measured from the date of the issuance of the notice of intent to the date a record of decision is signed.

§ 1502.7 Page limits

We support the proposal by CEQ to add a condition that a senior agency official must approve exceeding the page limit in writing. However, because the page limit should usually be 150 pages, with 300 pages being the limit only for projects of unusual scope or complexity, we would suggest requiring senior agency approval to exceed 150 pages, not 300 pages. Without this change, agencies may view 300 pages, not 150 pages, as the binding limit for environmental impact statements of normal scope and complexity.

Current text: The text of final environmental impact statements (e.g., paragraphs (d) through (g) of § 1502.10) shall normally be less than 150 pages and for proposals of unusual scope or complexity shall normally be less than 300 pages.

CEQ’s proposed rule: The text of final environmental impact statements (e.g., paragraphs (a)(4) through (6) of § 1502.10) shall be 150 pages or fewer and, for proposals of unusual scope or complexity, shall be 300 pages or fewer unless a senior agency official of the lead agency approves in writing a statement to exceed 300 pages and establishes a new page limit.

Our suggestion: The text of final environmental impact statements (e.g., paragraphs (a)(4) through (6) of § 1502.10) shall be 150 pages or fewer unless a senior agency official of the lead agency approves in writing a statement to exceed 150 pages and establishes a new page limit. For proposals of unusual scope or complexity, the senior agency official shall not normally approve a limit exceeding 300 pages.

§ 1502.22 Incomplete or unavailable information

CEQ invites comment on whether the “overall costs” of obtaining incomplete or unavailable information warrants further definition to address whether certain costs are or are not “unreasonable.”

Incomplete or unavailable information causes significant problems for effective federal decision-making. Agencies are reluctant to follow the procedure in proposed 1502.22(c) even if the costs of gathering information are unreasonable or exorbitant for fear that the determination that the costs of gathering the information are too high will be challenged in court.

As an example, consider the rule banning civil supersonic flight over the United States in 14 CFR 91.817. Despite 60 years of research by NASA testing human subjects exposed to sonic booms in boom simulators and on military bases, the Federal Aviation Administration has not revised the ban with a suitable noise standard. NASA is currently spending hundreds of millions of dollars to develop an experimental supersonic aircraft that can be used to characterize human response to sonic boom in order to supply the FAA with the data it needs to revise the ban. The spending includes a $247.5 million contract with Lockheed Martin to complete the design and build the aircraft, but that number does not include contracts for preliminary design or the cost of operating the aircraft and performing the studies to determine human response to sonic boom.433 J. D. Harrington, “NASA Awards Contract to Build Quieter Supersonic Aircraft,” April 3, 2018, http://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasaawards-contract-to-build-quieter-supersonic-aircraft.

The rule on incomplete or unavailable information could draw a distinction between data that already exists but which costs money to obtain and data that does not exist and which costs money to create. For example, if a relevant commercial data set exists and can be acquired at reasonable cost, it stands to reason that an agency should obtain it and use it to inform its environmental impact statement. On the other hand, if an expensive science project is required to create data to inform the environmental impact statement, an agency should proceed with the environmental impact statement without the data. In practice, this requires clear regulations so that the agency can proceed without fear of being sued.

It seems probable to us that Congress did not intend environmental review under NEPA to authorize or require non-scientific agencies to conduct original research but instead to apply the best existing scientific knowledge to the evaluation of environmental effects. The regulations in this section should make clear that environmental review should only entail gathering existing scientific research and data, reinforcing the proposed rule in § 1502.24, which states that “Agencies shall make use of reliable existing data and resources and are not required to undertake new scientific and technical research to inform their analyses.”

In addition, obtaining relevant information should not extend the timeframe for a decision beyond the period in § 1501.10.

CEQ’s proposed (b) and (c):

(b) If the incomplete information relevant to reasonably foreseeable significant adverse impacts is essential to a reasoned choice among alternatives and the overall costs of obtaining it are not unreasonable, the agency shall include the information in the environmental impact statement.

(c) If the information relevant to reasonably foreseeable significant adverse impacts cannot be obtained because the overall costs of obtaining it are unreasonable or the means to obtain it are not known, the agency shall include within the environmental impact statement:

[…]

Our suggestion:

(b) If the incomplete information relevant to reasonably foreseeable significant adverse impacts exists, is essential to a reasoned choice among alternatives, the overall costs of obtaining it are not unreasonable, and can be obtained in a timeframe consistent with the requirements of § 1501.10, the agency shall include the information in the environmental impact statement.

(c) If the information relevant to reasonably foreseeable significant adverse impacts cannot be obtained because it has not yet been created, the overall costs of obtaining it are unreasonable, it cannot be obtained in a timeframe consistent with the requirements of § 1501.10, or the means to obtain it are not known, the agency shall include within the environmental impact statement:

[…]

§ 1506.1 Limitations on actions during NEPA process

CEQ invites comments on § 1506.1. We believe paragraph (b) goes beyond the mandate in the NEPA statute and could be deleted or amended to reflect that NEPA does not ban otherwise-legal private action.

Both the current and the proposed paragraph (b) provide that if an agency becomes aware that a non-Federal applicant is about to take an action within its jurisdiction concerning the proposal that would have an adverse environmental impact or limit the choice of reasonable alternatives it shall promptly notify the applicant that the agency will take appropriate action to ensure that the objectives and procedures of NEPA are achieved

If the action contemplated in this paragraph is the action for which agency authorization is being sought, then the paragraph is redundant. If a non-Federal applicant needs Federal authorization to take an action, then that action is illegal absent authorization. Where this provision binds, then, is actions related to the proposal that do not normally require Federal authorization.

As an example, consider a construction project consisting of two elements, one which requires Federal authorization and an adjacent element which does not but which still falls under the jurisdiction of the authorizing agency. A non-Federal entity is normally within its rights to work on the element of the construction project that does not require Federal authorization. The entity is also within its rights to apply for authorization to work on the element of the construction project that requires Federal authorization. Paragraph (b) could be and often is interpreted to mean that if the entity applies for authorization to work on the element of the construction project that requires Federal authorization, the authorizing agency may take steps to prohibit its work on the adjacent element of the project that does not require authorization, on the grounds that the connected activity may have an environmental impact or that ongoing commitment of resources could limit the choice of reasonable alternatives. Our view is that applicants should not forfeit freedom of action in one element of the project to apply for authorization in others.

It is noteworthy that the requirements of the substantive provisions in § 102.2 of NEPA apply only to “all agencies of the Federal government.” NEPA does not and cannot make the activities of non-Federal actors illegal. Paragraph 1506.1(b) only requires agencies to “notify the applicant that the agency will take appropriate action to ensure that the objectives and procedures of NEPA are achieved.”

Analysis of this clause shows how unnecessary it is. Federal agencies should always act appropriately and do not need to be told or authorized by regulation to act appropriately. Reading the appropriate action clause out of the regulation, then, yields, “notify the applicant that the agency will ensure that the objectives and procedures of NEPA are achieved.” As CEQ states earlier in the proposed rule, “The purpose and function of NEPA is satisfied if Federal agencies have considered relevant environmental information and the public has been informed regarding the decision making process.” Assuming “objectives” and “purpose” are interchangeable, it is difficult to see how otherwise legal non-Federal actions interfere with the Federal agency considering relevant environmental information or informing the public regarding the decision-making process

What is left then is to “notify the applicant that the agency will ensure that the procedures of NEPA are achieved.” The procedures referenced here cannot themselves be paragraph (b), as interpreted to limit private adjacent actions, because that would be a circular exercise. Moreover, private adjacent actions do not prevent agencies from following the other procedures laid out in these regulations.

Our recommendation is to strike paragraph (b) entirely. Non-Federal entities should be able to take actions when doing so is otherwise legal and no authorizations are needed for that specific action. There may be occasions when a negative response on a request for federal authorization results in a material loss by non-Federal entities in an adjacent part of the project. It is not the job of NEPA regulations to prevent such risk-taking.

Another concern with our approach may be that these actions by non-Federal entities would affect the Federal decision making calculus. For example, by incurring sunk environmental costs in permit-adjacent parts of the project, applicants could reduce the forward-looking environmental costs of the project as a whole. Alternatively, by starting work on permit-adjacent parts of the project, applicants could make some considered alternatives non-viable. The 1978 rulemaking indicated that 1506.1 was necessary “because of the possibility of prejudicing or foreclosing important choices.”44Council on Environmental Quality, “National Environmental Policy Act— Regulations,” Federal Register 43 (November 29, 1978): 55986. But the text of NEPA does not put the onus on non-Federal entities to make the Federal decision making calculus simple—NEPA applies only to agencies of the Federal government. Agencies cannot reasonably expect the world to remain static while they deliberate for years and sometimes decades on authorizations. Removing paragraph (b) could incentivize agencies to make decisions in a timely manner.

Paragraph (b) is not implied or mandated by the NEPA statute, and it is not necessary to ensure that non-Federal entities abide by rules concerning Federal authorizations of activities that could have a significant effect on the human environment. Consequently, we recommend deletion of paragraph (b).

Current paragraph (b): If any agency is considering an application from a non-Federal entity, and is aware that the applicant is about to take an action within the agency’s jurisdiction that would meet either of the criteria in paragraph (a) of this section, then the agency shall promptly notify the applicant that the agency will take appropriate action to insure that the objectives and procedures of NEPA are achieved.

CEQ’s proposed paragraph (b): If any agency is considering an application from a non-Federal entity, and is aware that the applicant is about to take an action within the agency’s jurisdiction that would meet either of the criteria in paragraph (a) of this section, then the agency shall promptly notify the applicant that the agency will take appropriate action to ensure that the objectives and procedures of NEPA are achieved. This section does not preclude development by applicants of plans or designs or performance of other activities necessary to support an application for Federal, State, Tribal, or local permits or assistance. An agency considering a proposed action for Federal funding may authorize such activities, including, but not limited to, acquisition of interests in land (e.g., fee simple, rights-of-way, and conservation easements), purchase of long lead-time equipment, and purchase options made by applicants.

Our recommendation: [remove paragraph (b)]

§ 1506.8 Proposals for legislation

CEQ also invites comment on whether the legislative EIS requirement should be eliminated or modified. We believe it could be removed as it is unenforceable and potentially unconstitutional.

As CEQ notes earlier in the NPRM, NEPA does not include a private right of action. Court challenges alleging non-compliance with NEPA are brought under the Administrative Procedure Act. Per Franklin v. Massachusetts, the President’s actions are not reviewable under the APA.45 Franklin v. Massachusetts, 505 U.S. 788 (U.S. 1992). As the President is the party that formally proposes legislation on behalf of the Executive Branch, failure to include an environmental impact statement along with proposed language cannot be challenged in court. Therefore, compliance with § 1506.8 is not enforceable.

Second, as CEQ notes, the Recommendations Clause of the U.S. Constitution provides that the President shall recommend for Congress’ consideration ‘‘such [m]easures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.’’ We do not think Congress can constitutionally erect legal obstacles or conditions limiting the President’s ability to recommend measures.

Our recommendation: [remove § 1506.8]

§ 1508.1(q) Definition of major Federal action

CEQ invites comment on whether and how to exclude certain categories of actions common to all Federal agencies from the definition of major Federal action.

We agree with the approach taken by CEQ to strike the sentence, “Major reinforces but does not have a meaning independent of significantly,” based on longstanding principles of statutory construction as well as the legislative history of NEPA. In our view, minor or routine Federal actions, even those that could “significantly affect[] the quality of the human environment,” should not be subject to review under NEPA because otherwise the word “major” would be given no effect. The definition in this section needs additional revision to fully draw out the distinction between major and non-major actions.

For guidance in interpreting the word “major” we can look to Congress’s definition of “major rule” in the Congressional Review Act. Congress considers a rule to be major if it is likely to result in:

(A) an annual effect on the economy of $100,000,000 or more;

(B) a major increase in costs or prices for consumers, individual industries, Federal, State, or local government agencies, or geographic regions; or

(C) significant adverse effects on competition, employment, investment, productivity, innovation, or on the ability of United States-based enterprises to compete with foreign-based enterprises in domestic and export markets.46Congressional Review Act, U.S.C., vol. 5, 1996.

Therefore, we propose to modify the definition in § 1508.1(q) by adding a new subparagraph (3) that outlines these conditions.

Suggested new subparagraph (3): A Federal action shall not be considered major unless it is likely to result in:

(i) an annual effect on the economy of $100,000,000 or more;

(ii) a major increase in costs or prices for consumers, individual industries, Federal, State, or local government agencies, or geographic regions; or

(iii) significant adverse effects on competition, employment, investment, productivity, innovation, or on the ability of United States-based enterprises to compete with foreign-based enterprises in domestic and export markets.

Support for other proposed changes

CEQ’s proposed rule contains many positive steps that could streamline and rationalize environmental review. We support the following proposed changes:

A. Proposed Changes Throughout Parts 1500–1508

• Edits throughout Parts 1500–1508 to make the regulations clearer, more readable, and consistent with modern usage.

• Changes reflecting executive orders or to ensure consistent use of legal terms.

• Use of the term “decision maker” to refer to individuals responsible for making decisions on agency actions and defining “senior agency official” to refer to agency officials with responsibility for NEPA compliance.

• The presumption of electronic distribution of materials

• The use of the term “practicable” and “as soon as practicable” in lieu of “possible” and “no later than immediately,” and the term “agency NEPA procedures.”

B. Proposed Revisions To Update the Purpose, Policy, and Mandate (Part 1500)

• Changes to § 1500.1(a) to summarize section 101 of NEPA including reflecting the Act’s procedural nature.

• Changes to § 1500.1(a) regarding NEPA’s purpose and function, which are consistent with case law.

• Removal of confusing language in § 1500.1(a) about “action forcing.”

• Consolidation and edits of § 1500.1(b) and (c) to concisely emphasize that the regulations intend to generate timely and efficient federal decisions and to consider environmental information early in the process.

• Removal of § 1500.2 as duplicative of subsequent sections.

• The addition of text in § 1500.3(a) to provide that “Agency NEPA procedures to implement these regulations shall not impose additional procedures or requirements beyond those set forth in these regulations, except as otherwise provided by law or for agency efficiency.”

• The proposed provisions on exhaustion in § 1500.3(b). This provision could limit weaponization of NEPA as discussed in a 2018 hearing in the House of Representatives.47United States. Congress. House. Committee on Natural Resources, The Weaponization of the National Environmental Policy Act and the Implications of Environmental Lawfare: Oversight Hearing Before the Committee on Natural Resources, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Fifteenth Congress, Second Session, Wednesday, April 25, 2018, 2018.

• The proposed revisions in § 1500.3(c) on legal actions regarding NEPA compliance.

• The proposed revisions in § 1500.3(d) on remedies.

• The provision on severability in § 1500.3(e).

• The logical reordering of paragraphs in §§ 1500.4–1500.5

C. Proposed Revisions to NEPA and Agency Planning (Part 1501)

• Removal of the duplicative section on purpose and its replacement with a section on NEPA threshold applicability analysis (§ 1501.1).

• Granting agencies discretion on NEPA process integration (§ 1501.2(a)).

• Clarifying that agencies should consider environmental documents alongside economic and technical analyses (§ 1501.2(b)(2)).

• Changes to § 1501.3 to create a decisional framework including all three levels of NEPA review. We especially support the removal of the controversy criterion in text moved from § 1508.27, as controversy is not discussed in NEPA.

• The new § 1501.4 on categorical exclusions, although as discussed above we have a suggestion for regular review to ensure agencies do not neglect the creation of new categorical exclusions.

• Creation of new sections on environmental assessments (§ 1501.5) and findings of no significant impact (§ 1501.6), especially the page limit on environmental assessments. • Modifications to the sections on lead agencies (§ 1501.7) and cooperating agencies (§ 1501.8) to improve coordination and efficiency.

• Changes to provide for additional flexibility in the scoping process (§ 1501.9).

• The addition of new presumptive time limits in § 1501.10, noting also our comments above suggesting to reduce the presumptive amount of time allotted when an EIS is preceded by an environmental assessment. We especially support striking “the degree to which the action is controversial,” which has no basis in NEPA.

• Moving sections on tiering (§ 1501.11) and incorporation by reference (§ 1501.12) to this more general part, and the edits to these sections.

D. Proposed Revisions to Environmental Impact Statements (EISs) (Part 1502)

• The requirement for a senior agency official to approve in writing an increase in the page limit (§ 1502.7). However, we have a suggestion discussed above to improve this provision.

• The changes in §1502.9, which improve clarity.

• Edits to the format of EISs (§ 1502.10) and their cover sheets (§ 1502.11). We especially support the addition of § 1502.11(g), which requires the cover sheet to summarize the costs of producing the EIS.

• Removal of the word “controversy” in § 1502.12. We note a minor typographical error in this paragraph regarding parentheses.

• Changes, including new sections, throughout § 1502.13 to § 1502.21 to guide EIS content.

• The minor edits in § 1502.22 on incomplete or unavailable information, although we discuss above an additional suggested change.

• The clarification that agencies are not required to conduct their own new research in § 1502.24.

• The minor changes in § 1502.25

E. Proposed Revisions To Commenting on Environmental Impact Statements (Part 1503)

• The changes throughout §§ 1503.1–4 to promote more direct conversation about the environmental effects of an action, particularly the sharpening of the requirement for comments to be as specific as possible (§ 1503.3).

F. Proposed Revisions to Pre-Decisional Referrals to the Council of Proposed Federal Actions Determined To Be Environmentally Unsatisfactory (Part 1504)

• The change in § 1504.2 to add economic and technical considerations as a criterion for referral.

• The modernization and simplification of § 1504.3.

G. Proposed Revisions to NEPA and Agency Decision Making (Part 1505)

• Moving § 1505.1 on agency decision making procedures to Part 1507 on agency compliance.

• Changes to clarify § 1505.2.

H. Proposed Revisions to Other Requirements of NEPA (Part 1506)

• The changes to § 1506.1 on limitations on actions during the NEPA process, except that we have proposed to strike paragraph (b) as discussed above.

• The changes to §§ 1506.2–7, which we see as modernizing the regulations to comport with current practice or best practices.

• Updates to § 1506.8 as an improvement over current text, although we recommend deleting § 1506.8 as unenforceable and possibly unconstitutional as discussed above.

• The addition of a new § 1506.9 on proposals for regulations, particularly the recognition that existing substantive standards can ensure consideration of environmental issues.

• The clarifications and other changes in §§ 1506.10–13.

I. Proposed Revisions to Agency Compliance (Part 1507)

• The revisions to agency compliance rules that CEQ proposes to Part 1507.

J. Proposed Revisions to Definitions (Part 1508)

• The definitions proposed by CEQ in Part 1508, noting that we have suggested an additional change to the definition of “major Federal action” above.

Regulations.gov

Regulations.gov