Introduction

With state budget surpluses and record high state reserve account balances, Missouri lawmakers are considering policy reforms that continue to support the state’s growth while leaving some reserves available for potential economic downturn in the future. One reform is in a number of current bills in the legislature proposing to reduce the Missouri corporate income tax with gradual rate reductions over the next four-to-five years.1Missouri Senate Bills 93 and 135 and House Bill 660 propose a gradual phase out of the state corporate income tax over the next four-to-five years, with annual reductions in the current state corporate income tax rate of 4.0% of between 1.0 and 0.8 percentage points per year. See Missouri Senate, Bill Search, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.senate.mo.gov/BTSSearch/Default?SearchTerm=corporate+income+tax&Submit=Submit. In 2018, the Missouri legislature passed Senate Bill 769, which requires that whenever the state corporate income tax is lowered, the financial institutions tax on banks, credit institutions, and other financial institutions receive a proportional reduction. Missouri’s current 4% corporate income tax rate (4.48% on financial institutions) is one of the lowest in the country.2See Tax Foundation, “How High are Corporate Income Tax Rates in Your State?” accessed January 30, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/state-corporate-income-tax-rates-and-brackets/. This state corporate income tax only represents a small percentage of state revenues, and its removal would have a positive effect on Missouri businesses.

In this article, I use an open source model of business investment incentives to quantify and compare the effects of two sizes of Missouri corporate income tax rate cuts on both the investment incentives faced by businesses in the state and also on state revenues. Because all of our modeling structure is open source, I provide all of our code and source data in a way that is easy to replicate and customize.3All data, analyses, and images in this article can be reproduced using the resources in the GitHub repository for this article at https://github.com/TheCGO/MO-CorpRateCut. The code for replicating the analyses and creating the images can be run locally on your machine using the Jupyter notebook MO_CorpRateCut.ipynb or can be run from your browser using resources in the cloud from this Google Colab notebook.

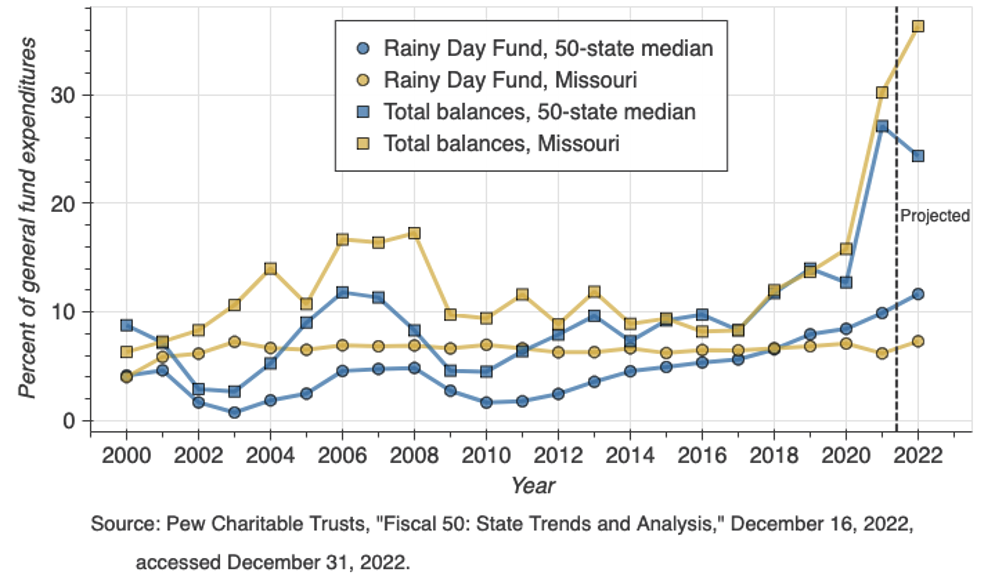

Budget surpluses, tax revenues, and rainy day funds are projected to be at 20-year highs in most states for year end 2022, thanks to a surprisingly resilient US economy.4To account for accumulated state surpluses, I use two accounting concepts that are common across states. Total reserves and balances are states’ intentional savings as well as dollars left over in the general fund. See Justin Theal and Joe Fleming, “Budget Surpluses Push States’ Financial Reserves to All-Time Highs”, Article, PEW Charitable Trusts (May 10, 2022). Rainy day funds, also called reserve funds or stabilization accounts, are a subset of total reserves and balances. See Tax Policy Center, “What are state rainy day funds, and how do they work?”, Briefing Book, The State of State (and Local) Tax Policy, Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute and Brookings Institution (accessed Dec. 30, 2022). Rainy day funds are accounts to which state budget surpluses are automatically transferred, subject to varying rules across states. Missouri is no exception, with a projected record high rainy day fund balance of $772 million at the end of 2022 and a record high total reserves and balances of $3.85 billion.5See Pew Charitable Trusts, “Fiscal 50: State Trends and Analysis: Reserves and Balances”, updated Dec. 16, 2022 (accessed Dec. 31, 2022). Figure 1 shows the time series from 2000 to the estimated values of 2022 of the rainy day fund balance and the total reserves and balances as a percent of general fund expenditures for both the state of Missouri and for the 50-state median values.

Figure 1. Rainy day fund and total reserves as a percent of general fund expenditures, Missouri and 50-state median: 2000-2022

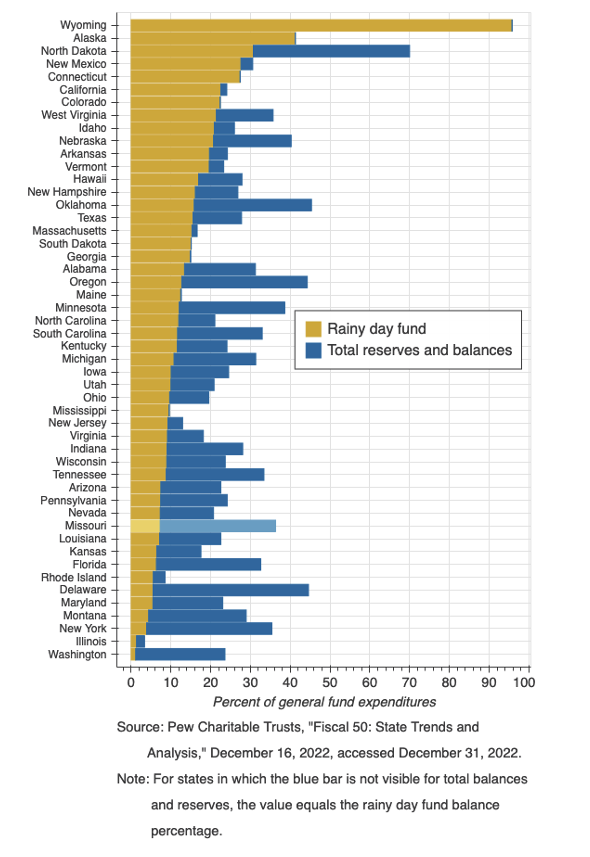

Figure 2 shows the estimated 2022 rainy day fund balances and total reserves and balances as a percent of general fund expenditures for each state, ranked in descending order by rainy day fund balances. Missouri’s rainy day fund is more restricted in its use than most state rainy day funds, with strict use and repayment requirements outlined in the state constitution.6See discussion on the Missouri rainy day fund on page 14 in Corianna Baier and Elias Tsapelas, “Making Missouri Resilient: Assessing State and Local Government Recession Preparedness,” Report, Show-Me Institute, June 2021. As such, Missouri total balances and reserves is a better measure of funds the state can draw on to pay for policy reforms like a tax cut. If we rank states in descending order by the broader total balances and receipts as a percent of general fund expenditures, Missouri has the 9th highest balance among US states.

Figure 2. Estimated 2022 rainy day fund balances and total reserves and balances as percent of general fund expenditures

Table 1 shows the number of states that had record highs in either of these two reserve categories in either 2021 or 2022. For rainy day fund balances, 36 states had record highs in 2022, and 29 states had record highs in 2021. Missouri had a record high rainy day fund balance in 2022. For total balances and reserves, 26 states had record highs in 2022, and 42 states had record highs in 2021. Missouri had a record high in its total balances and reserves in both 2021 and 2022.

Tempering the optimism from the current surpluses and reserve balances are the continuing risks in 2023 of high interest rates, inflation, and potential economic slowdown. As many state legislatures come into session in early 2023, these policymakers are balancing the opportunity to draw down these reserves with the risk of needing reserve funds in a downturn.

In this vein, Missouri legislators are proposing a phased-in reduction of the state’s corporate income tax, along with the financial institutions tax, over a four- or five-year period.7Missouri Senate Bills 93 and 135 and House Bill 660 propose a gradual phase out of the state corporate income tax over the next four-to-five years, with annual reductions in the current state corporate income tax rate of 4.0% of between 1.0 and 0.8 percentage points per year. See Missouri Senate, Bill Search, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.senate.mo.gov/BTSSearch/Default?SearchTerm=corporate+income+tax&Submit=Submit. In 2018, the Missouri legislature passed Senate Bill 769, which requires that whenever the state corporate income tax is lowered, the franchise tax on banks, credit institutions, and other financial institutions receive a proportional reduction. As I show in Section 2, the Missouri corporate income tax represents a small fraction of state tax revenue and would result in a moderate reduction in state reserve balances. In Section 3, I use the open source Cost of Capital Calculator model to simulate the effects of two potential reforms on business incentives for investment.8The open source Cost of Capital Calculator model simulates the effect of tax policy on the investment incentives of corporate and non-corporate businesses. Cost of Capital Calculator documentation is available at https://ccc.pslmodels.org/, and its source code is available at https://github.com/PSLmodels/Cost-of-Capital-Calculator.

My simulations in Section 3 show that reducing the Missouri corporate income tax and financial institutions tax by half–from the current tax rates of 4.00% and 4.48%, respectively, to 2.00% and 2.24%–results in a moderate decline in state tax revenue of $474 million if the reform were enacted for 2023. This rate cut would also reduce the marginal effective tax rate (METR) on Missouri businesses, a broader measure that includes many factors, from the current 3.24% to 2.98%. This decline in METR represents an increase in business investment incentives of 8%. Fully repealing the Missouri corporate income tax and and financial institutions tax would result in a larger decline of $948 million. This bigger reform would result in a 16% increase in Missouri business investment incentives, resulting from a reduction in business marginal effective tax rates from 3.24% to 2.72%.

The first reform of cutting the corporate income tax rate and financial institutions tax rate in half is more in line with the bills currently in the Missouri legislature. But both the 50% rate cut with a revenue cost of $474 million and the full repeal with a revenue cost of $948 million are within realistic budgetary options in a state with the 9th highest total reserves and balances in the country of $3.85 billion.

Missouri Business Tax Landscape

Excluding licenses, permits, and fees, and the gaming gross receipts tax, Missouri currently imposes three main categories of taxes on business income and sales: corporate income tax, financial institutions tax, and sales and use taxes. Table 2 shows the total revenue from each of these three tax revenue categories and the percent of total state revenue in fiscal years 2021 and 2022.9It is important to recognize that Missouri tax revenues represent the tax liabilities of Missouri individual and business tax filers minus their redeemed Missouri transferable tax credits. Missouri issues transferable and non transferable tax credits for business development across twelve categories. But these credits can be bought and sold on the open market by both businesses and individuals, although these markets are somewhat opaque. So any revenue values are net of redeemed Missouri tax credits. For a discussion of Missouri transferable credits, see Nicole Galloway, CPA, “Tax Credit Programs,” Report No. 2022-011, Missouri State Auditor, February 2022. See also Missouri Department of Revenue, “Tax Credit and Total Business Locations Reports”, quarterly (accessed Mar. 10, 2023). I have broken out sales and use taxes into both state and local revenues. I include the local sales and use tax component because it is equal in size to the state portion. And taken together, state and local Missouri sales and use tax revenue represents more than 40% of total state revenue. I also exclude the property tax because it is administered locally and varies from city to city.

Corporate Income Tax

The Missouri corporate income tax is a tax on net business earnings or income. It is similar to the federal corporate income tax and is based off of federal taxable income reported on the federal tax return.10See Missouri Department of Revenue, “Corporate Income Tax”, (accessed Mar. 7, 2023). The Missouri corporate income tax rate is currently 4.0% of state taxable income. As shown in table 2, Missouri’s corporate income tax represented 4.1% of gross state revenue in fiscal years 2021 and 2022, respectively.11See Missouri Department of Revenue, “Financial and Statistical Report, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2022”, (accessed Mar. 7, 2023).

Financial Institutions Tax

The Missouri financial institutions tax is similar to the corporate income tax in that it is a tax on the net earnings or income of financial institutions operating in the state. These financial institutions include banks, trust companies, credit institutions, savings and loan associations, and credit unions. The current financial institutions tax rate is 4.48%. This tax for these institutions is administered and calculated differently from the corporate income tax from the previous section mainly in how net earnings or taxable income is defined.12See Missouri Department of Revenue, “Financial Institutions Tax”, (accessed Mar. 7, 2023). As shown in table 2, Missouri’s financial institutions tax represented only 0.2% of gross state revenue in fiscal years 2021 and 2022, respectively.13See Missouri Department of Revenue, “Financial and Statistical Report, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2022”, (accessed Mar. 7, 2023).

State and local sales and use tax

The sales and use tax in Missouri is a tax on the sale of different types of goods transacted in the state or used in the state.14See Missouri Department of Revenue, “Sales/Use Tax”, (accessed Mar. 10, 2023). Although these sales and use taxes are paid by both individuals and businesses in Missouri, at least some of the incidence of sales and use taxes paid by individuals falls also on the selling businesses. As such, the Missouri sales and use taxes are a significant part of the state’s business tax structure.

A portion of Missouri’s sales and use tax structure is decided at the state level and supplies various state-level funds. These state sales and use tax rates vary from 0.1% to 5%, with the most common rate being the 3% general sales tax.15See Missouri Department of Revenue, “State Sales and Use Tax”, in Financial and Statistical Report, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2022, (accessed Mar. 7, 2023). Local political subdivisions in Missouri are also authorized to enact local sales taxes “if approved by a specified percentage of voters.” And these local sales and use tax rates vary across geographies. Fifteen industries are exempted from the state and local sales and use taxes.16See Missouri Department of Revenue, “Missouri Sales and use Tax Exemptions and Exclusions from Tax”, (accessed Mar. 10, 2023). This Missouri Sale as Use Tax Lookup Dashboard is an interactive map that shows how overlapping geographic jurisdictions in the state can cause total sales and use tax burdens to vary significantly, https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/1ff88616ff3341c5ad31550471a75296/.

As shown in table 2, state and local sales and use taxes represented more than 40% of total Missouri revenue in FY 2021 and 2022. Combined Missouri sales and use taxes are the second largest revenue category in Missouri state tax revenues, following only individual income tax revenues which represented just over 45% of total state revenues in FY 2021 and 2022.

Investment Incentives

In this section, I compare the effects of two potential reforms to Missouri’s corporate tax structure. The first experiment is to cut the current corporate income tax rate and financial institutions tax rate in half, from 4.00% and 4.48%, respectively, to 2.00% and 2.24%. The second experiment is to estimate the effect of fully repealing the Missouri corporate income tax and financial institutions tax. Table 3 shows a summary of the policy reforms and their corresponding effects on businesses’ incentives to invest and their effect on state revenues. I simulate these reforms using the open source Cost of Capital Calculator model.17All data, analyses, and images in this article can be reproduced using the resources in the GitHub repository for this article at https://github.com/TheCGO/MO-CorpRateCut. All data and analysis of the simulation of Missouri corporate tax reforms in the first column of Table 3 were performed using the open source Cost of Capital Calculator, which simulates the effect of tax policy on the investment incentives of corporate and non-corporate businesses. The code for these experiments can be replicated by running the Jupyter notebook MO_CorpRateCut.ipynb locally on your machine or can be run from your browser using resources in the cloud from this Google Colab notebook.

The Cost of Capital Calculator model calculates the marginal effective tax rate (METR) on new investments, given policy and economic characteristics for the average business.18The Cost of Capital Calculator methodology follows closely Larry Ozanne and Paul Burnham, “Computing Effective Tax Rates on Capital Income,” Technical Report, Congressional Budget Office (Dec. 2006). The METRs in the first column of table 3 differ from the corporate income tax rate and from the financial institutions tax rate because those two statutory rates are only one respective component of the Cost of Capital Calculator METR calculation. The computed METR is a function of the average real return on investment, inflation, federal corporate income tax rates, state income tax rates, investment tax credits, depreciation, bonus depreciation, franchise taxes, gross receipts taxes. For this reason, the METR is a better indication of how much business investment incentives are affected by policy changes than is the change in the corporate income tax rate alone.

The model calculates the METR on machinery and equipment, buildings, and intangible assets, but I focus here on investment in machinery and equipment that is financed with retained earnings by a corporate business entity.19More specifically, we assume a piece of equipment with a 7-year depreciable life and a rate of physical depreciation of 10.3% per year, similar to special industrial machinery (BEA Code EI40). More details and code to reproduce the results here are available in the Jupyter notebook for these analyses MO_CorpRateCut.ipynb or the Google Colab notebook. The METR is a forward looking measure and takes into account tax rates as well as deductions, such as the depreciation of a capital asset. The METR therefore will vary according to not just corporate income tax rates, but the availability of investment tax credits, the ability to deduct interest costs, and the rates of capital cost recovery, among other features of a tax system.

Under current federal and Missouri law, state and federal taxes combine for an effective marginal tax rate on new investments in machinery and equipment for Missouri businesses of 3.24% as shown in the “Current law” row in Table 3. Under current law, Missouri businesses pay the federal corporate income tax (CIT), are allowed to deduct 80% of bonus depreciation from the federal CIT taxable income, and pay the Missouri corporate income tax.

Cutting in half the Missouri corporate income tax and financial institutions tax rates

The first reform in Table 3 is cutting the Missouri corporate income tax rate and financial institutions tax rate in half. This experiment is similar to the reforms currently proposed in the Missouri legislature.20See Missouri Senate Bills 93 and 135 and House Bill 660 that propose a gradual phase out of the state corporate income tax over the next four-to-five years, with annual reductions in the current state corporate income tax rate of 4.0% of between 1.0 and 0.8 percentage points per year. See Missouri Senate, Bill Search, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.senate.mo.gov/BTSSearch/Default?SearchTerm=corporate+income+tax&Submit=Submit. This policy reform involves reducing the current CIT and FIT rates from 4.00% and 4.48%, respectively, to 2.00% and 2.24%. I estimate that the cost of cutting the Missouri CIT and FIT in half would be $474 million, half the total revenue from the CIT and FIT in FY 2022.

This cost is a manageable size, given Missouri’s current $3.85 billion total reserves and the strategy in the current legislative bills to gradually phase in the cut over the next four-to-five years. And this corporate income tax cut would increase business investment incentives by 8%, reducing Missouri marginal effective tax rates from their current 3.24% to 2.98%.

Repealing the Missouri corporate income tax and financial institutions tax

The second reform in Table 3 is fully repealing the Missouri corporate income tax and financial institutions tax. I estimate that the cost of repealing the Missouri CIT and FIT would be the full $948 million total revenue from the CIT and FIT in FY 2022. And repealing the CIT and FIT would increase business investment incentives by 16%, reducing Missouri marginal effective tax rates from their current 3.24% to 2.72%.

Conclusion

In this article, I describe the current situation of record high balances in state rainy day balances and in total reserves and balances across the US and in Missouri. I describe the three main components of Missouri business tax policy and simulate the effects of two pro-growth reforms that reduce marginal effective tax rates on business investment and also result in reductions on state tax revenues.

I find that the first reform of cutting the CIT and FIT in half would cost $474 million in tax revenue and would increase business investment incentives by 8%, cutting marginal effective tax rates on investment from 3.24% to 2.98%. I also simulate the larger reform of repealing both the Missouri CIT and FIT. This larger policy would cost $948 million in tax revenue and would increase business investment incentives by 16%, cutting marginal effective tax rates on investment from 3.24% to 2.72%.

Missouri has an opportunity in the face of current record surpluses to enact pro growth policy that balances the state’s track record of making Missouri an inviting place to live and work while maintaining reserves against any potential economic downturn. Cutting the Missouri CIT and FIT rates in half is a very safe option that balances those two incentives.